The Holbein Gate & the Secret Marriage of Anne Boleyn

In the early hours of the morning, on 25 January 1533, the slight figure of a woman made her way by flickering torchlight along the King’s Privy Gallery at Whitehall. Outside the window, blackness enshrouded the privy gardens below. She heard the night owl screech out its territorial cry, penetrating the stillness of the icy, winter’s morning. But her mind was elsewhere. The shadowy figure and her companion were heading for the Holbein Gate at the end of the gallery. In its upper chamber, the king impatiently anticipated the lady’s arrival. After around six years of waiting, Anne Boleyn was to finally marry the King of England in a pre-dawn ceremony, safe in the knowledge that she was already pregnant with Henry VIII’s longed-for heir.

This ceremony was to take place amidst the utmost secrecy. Contemporary letters tell us that even Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, did not know that the wedding had taken place until two weeks after the event, while Eustacy Chapuys was still guessing that a pre-Easter marriage was on the cards as late as the end of March!

But Anne was pregnant: there could be no further delays. However, there was a problem: Katherine of Aragon. Although separated from his wife, Henry was still married to her. The annulment of the marriage would not be ratified until a court found in the king’s favour at Dunstable toward the end of May. And so, according to the account written by Nicolas Harpsfield in the 1550s, with only three or four witnesses present (Sir Henry Norris, Thomas Heneage, Anne Savage, later Lady Berkeley, and possibly also a ‘groom’, thought likely to be William Brereton), the couple were joined together ‘secretly…very early before day’ in a building that was already renowned across Tudor London for its notably fine architecture: the Holbein Gate.

The Construction of the Holbein Gate: 1531-1532.

But what of this note-worthy landmark in which this significant Tudor event took place? What do we know of its history, appearance and why it was chosen as the place in which Anne Boleyn would marry her lover, Henry VIII? In the rest of this blog, we will explore the answers to these questions, so that we can delve behind the scenes of this much-recounted episode in Anne Boleyn’s life.

Let’s start with a myth that needs debunking. Despite its name, historians seem to agree that Holbein had nothing to do with the design of the gate. The reason that this cannot be so is to do with dates. Bear with me!

The Holbein Gate came into being as one of two gates bridging King Street, commissioned by Henry VIII after he ‘acquired’ York Place from the disgraced Thomas Wolsey in 1529. ‘Gates’ were usually entry points into and out of a city. The City of London had eight such gates; Ludgate, Newgate, Cripplegate etc. At Whitehall, the two gates that were constructed on Henry’s orders served two functions; they heralded the boundary demarcating the entry and exit into the royal enclave of Westminster along the principal street connecting Westminster with the rest of London: King Street. Secondly, they connected the enlarged Palace of Whitehall with the leisure complex and park lying to its west, on the far side of this main thoroughfare. The king needed a way of crossing the street so that he, and the court, could access the complex in comfort and without having to be seen by the common folk of London.

The Holbein Gate afforded such a practical solution – and in some style. Thomas Alvard was the principal paymaster for the renovation and development of, what would become, the Palace of Whitehall. According to his building accounts, the Holbein Gate was under construction from August 1531. In his book on Whitehall Palace, Simon Thurley notes that the gatehouse ‘rose rapidly’. By September, a pulley system was being put in place to heave the stone up to the upper floors, and by February 1532, decorative fleur-de-lys were being carved on its external facade.

By the time Holbein arrived in London for the second time, in early 1532, the gate was nearing completion; the accounts show no further payments for structural elements from this point forward. Instead, we read of workmen, such as John Wright, being paid for carving ‘two antelopes, two greyhounds, one lion and one dragon in the table over the bay windows’, as well as ‘two antyke heads’ to go in ‘the corbyll table of the seyde gate.’ Given the known dates of the work and the dates that we know Holbein was in England, we can rule out the former’s involvement in the creation of the eponymous gate.

The Appearance of the Gate

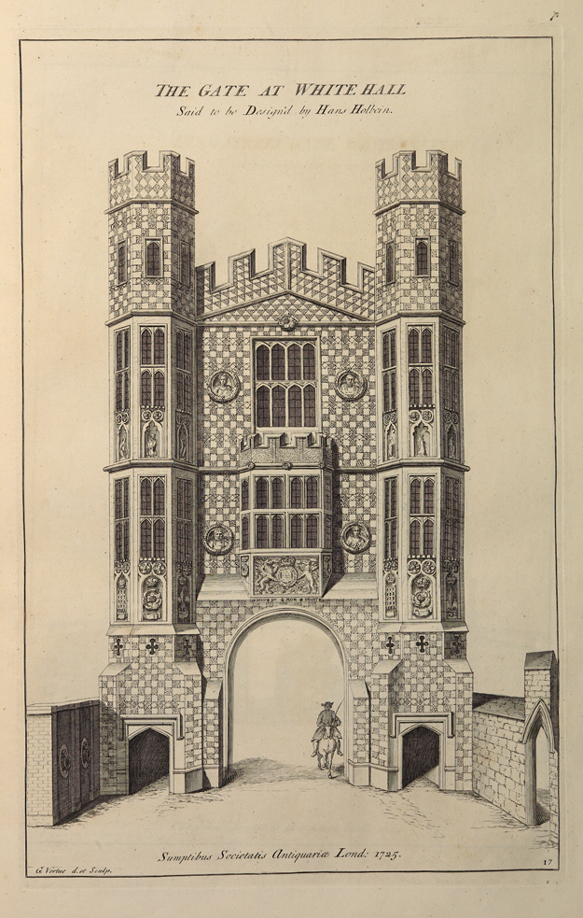

Probably one of the reasons that the Holbein Gate became so celebrated in London was on account of its striking external appearance. This mirrored the decoration adorning other parts of Wolsey’s original buildings, including the great hall, chapel and privy kitchen of York Place. Dark flint was juxtaposed against lighter stone, creating a chequer-board effect (illustrated in the drawing above). According to Thurley, over 600 tons of flint were brought from Wolsey’s college at Ipswich, especially for this project!

In layout, the gate was rectangular, with octagonal turrets at each corner. These turrets extended upwards, above the level of the parapet. Sitting directly over a central arch, which allowed for the passage of traffic along the street below, were likely three floors. The first was probably a simple passageway that connected the King’s Privy Gallery on the east, with the Tiltyard Gallery lying directly west of the gate. Perhaps it was this passageway which was once described as the ‘Darke Passage over the streete’. To the east of the Holbein Gate, in the Tiltyard Gallery, the king, his wife, and the court could watch jousting going on in the tiltyard below. Wonderfully, we know something of the appearance of this gallery, from a visitor’s account of Whitehall Palace, recorded in 1584. In this account, we hear the following:

‘A man, in whose keeping the rooms of the palace are, took us out of the garden and led us to see the inner part of the palace, to which there are only two keys. On mounting a staircase we got into a passage right across the tiltyard; the ceiling is gilt, and the floor ornamented with mats. There were fine paintings on the walls, among them the portrait of Edward, the present queen’s brother…If you stand before the portrait, the head, face, and nose appear so long and misformed that they do not seem to represent a human being, but there is an iron bar with a plate at one end fixed to the painting; if you lengthen this bar for about three spans and look at the portrait through a little hole made in the plate in this manner, you find the ugly face changed into a well-formed one.’ This portrait survives and is now in the National Portrait Gallery in London – AMAZING!.

To the east of the Holbein Gate was the King’s Privy Gallery, which I describe in some detail in this article. Originally, it had been Wolsey’s gallery at Esher, but after the Cardinal’s downfall, it was dismantled, and transported by river to Whitehall, where it was reassembled. The King’s Privy Gallery contained the most private of Henry’s chambers, accessible only to the most privileged noblemen and women of the king’s court.

On the morning of her wedding, it seems likely that Anne walked from the queen’s chambers, (which were sited close to the riverfront), through the palace and along the gallery in order to reach the Holbein Gate. Whitehall must have been was largely silent and yet to stir. We can only imagine what must have been going through her mind as she made her way towards the king’s innermost sanctum.

This ‘innermost sanctum’ relates to the upper chambers of the Holbein Gate, which were clearly an extension of some of the most private rooms used by Henry VIII. According to The Survey of London, ‘The lower storey in 1756, just before the demolition of the Gate, contained one large room and three closets. George Vurtue, English engraver and antiquary of the early eighteenth century describes the upper room as being ‘the king’s study’…’and was then [afterwards?] appointed for the reception of the letters and papers left by that prince and of other public papers.’ As the king’s study, this upper chamber would have indeed been amongst Henry’s most privy rooms.

We also know that these rooms occasionally served as a privy viewing gallery for any event taking place in King Street below. Henry observed Anne Boleyn’s procession from the Tower to Westminster Hall from the Holbein Gate on the day before her coronation. Three years later, Jane Seymour is recorded watching the king ride along King Street to open the parliament of 1536.

So, with these upper rooms of the Holbein Gate being the most inaccessible to the court, they afforded the intimacy and privacy desired by the king at what was a very delicate time. And while today, we might ordinarily think of royal weddings taking place in a great church, while this did happen (think Katherine of Aragon and Arthur Tudor at St Paul’s), it was not uncommon for the king to marry in either the king or queen’s closet. This was the case with both Jane Seymour and Katherine Parr, for example.

However, the clandestine nature of what took place on that January morning presumably meant that after the service, those who had been present quietly melted away back into the shadowy corridors of Whitehall. And as the sun rose on a new day, nobody but a handful of people knew that a new queen of England was sitting upon the English throne.

As for the Holbein Gate? Unlike the majority of Whitehall Palace, it survived the fire which destroyed most of the palace buildings in 1698. Its singular beauty and renown across the city preserved it for 30 years longer than its non-identical twin, sited further south along King Street. However, due to increasing pressure to widen the road in the mid-eighteenth century, the gate was finally demolished in August 1759. The then Duke of Cumberland salvaged the materials from the gate with the intention of re-erecting it at the end of the long walk in Windsor Great Park. Sadly, the plan was never executed and the leftover materials were subsequently incorporated elsewhere into several buildings in Windsor Park.

Sources

Whitehall Palace, by Simon Thurley.

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger.

On this Day in Tudor History by Claire Ridgway

Survey of London: Volume 14, St Margaret, Westminster, Part III: Whitehall II. Originally published by London County Council, London, 1931, via British History Online.

Journey Through England and Scotland Made by Lupold Von Wedel in the Years 1584 and 1585. Transactions Of The Royal Historical Society 1895 Vol IX 2nd Series.

I enjoy your posts so much! Thank you.

Thank you for reading – and for letting me know!

Hi – I am trying to understand why a couple of images of the Holbein Gate differ from others and would be very grateful for any help? One example can be found by searching ‘Holbein Gate, Whitehall Paul (after) Sandby (1731 – 1809) Hubert Arthur Finney’ – there are side towers which do not appear in most other contemporaneous images. Thanks.

Hi Adrian! Interesting. I hadn’t noticed. Off the top of my head, I don’t know BUT if I am looking at the right pictures, I can take a guess. The image you refer to seems to be the one of the gate after it was moved from Whitehall. I suspect that whoever moved it thought it needed decorating and added the turrets and onion domes – just because!