Rievaulx Abbey & the Brutal Dissolution of the Monasteries

This blog is adapted from an ‘on-location’ interview recorded for an episode of The Tudor History & Travel Show. Our guide is Michael Carter, a senior property curator at English Heritage. He specialises in English Monasticism and the Cistercian order. Read through to the end to find Michael’s top recommendations for the best monastic ruins to visit in England and where to see the few treasures that survive from the great age of medieval monasticism.

Note: You can listen to the podcast here or on most major podcast platforms, including Spotify, Apple Music, or Google Podcasts.

Introduction

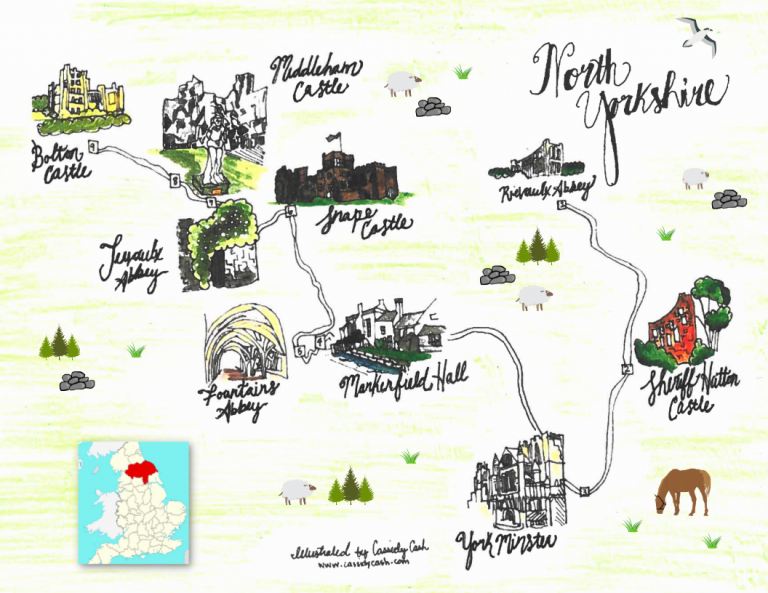

In 1132, a pioneering fraternity of Cistercian monks arrived in an isolated valley deep in the heart of the Yorkshire countryside. Their arrival and the subsequent founding of the abbey close to the River Rye profoundly influenced monasticism in the North of England, setting off a chain of events that would lead to the foundation of the mighty Fountains Abbey. This latter abbey was sited some 25 miles south of Rievaulx and would ultimately become the largest Cistercian Abbey in England.

The Cistercians led an austere, back-to-basics life, wearing white habits to symbolise poverty. This distinguished them from the Benedictine order, which hitherto had been Europe’s dominant form of monasticism. However, the Cistercians believed their Benedictine brothers had become increasingly lax in their religious observances. Through their adherence to austerity and poverty, the Cistercian order aimed to revive a purer interpretation of the rule of St. Benedict.

The abbey at Rievaulx would be the first Cistercian monastery founded in Northern England, spearheading the establishment of the order across the North and into Scotland.

The Founding of Rievaulx Abbey

Even today, Rievaulx Abbey’s position is utterly enchanting. It is arguably the most important Cistercian monastery in England, both architecturally and spiritually. Dating back to the twelfth century, Abbot Aelred built a complex of buildings and founded a vision of monasticism based upon love and inclusion. Aelred was the most famous and influential man associated with Rievaulx and was venerated as a saint after he died in 1167.

Locally, Rievaulx Abbey was an important monastery with an incredible reputation for holiness. Like many abbeys, it was deeply embedded in the local economy. At its height, in the late Middle Ages, there was a community of around 640 people. By the 1500s, this had declined to only 30 monks, although this remained a respectable number for a mid-ranking monastery like Rievaulx.

The ruins that survive of this once great monastery depict Cistercian monastic life. They also show us the substantial changes hewn in stone as Henry VIII’s edict to dissolve the monasteries swept across England. At the dawn of the Dissolution, Rievaulx was thriving religiously, economically, and politically. Contrary to Tudor propaganda about the widespread decline in standards and moral laxity in religious houses across the country, Rievaulx’s leaders were held in high regard in the Papal courts of Rome and the royal courts of England, France, and Scotland.

The visitations which heralded the onset of the Dissolution were nothing new. Monasteries had always been subjected to periodical ‘visitations’ by other Abbots or Bishops, who were there to ensure that the rules of St Benedict or St Augustine were followed according to doctrine. Furthermore, monasteries had been dissolved for various reasons as far back as the thirteenth century. In the early sixteenth century, Thomas Wolsey famously closed some lesser monasteries to fund his college in Ipswich. The Cardinal used the masterful legal work of Thomas Cromwell, then in Wolsey’s service, to accomplish his aims. It would be a valuable training ground for the man whose name would eventually be synonymous with the ‘Dissolution’.

Image: Author’s own

Today, the abbey’s chapter house, which dates to Aelred’s Abbotcy, is reduced to the foundation level. It is built in a characteristic horseshoe shape, with the tombs of various Abbots of Rievaulx embedded within the footprint of the house. Abbot William, the founding Abbot, was venerated here at Rievaulx as a saint, and a plaque on the wall tells us that this was the shrine of Albert William from 1131 to 45. Aelred was also buried here, although his remains were later moved to the church.

The chapter house was a place of sanctity. Every morning, the monks would gather to listen to a reading of the chapter on the Rule of St. Benedict. However, it also served as an administrative centre for the Abbey. Here, the Abbot and his brethren conducted the abbey business, such as signing contracts between the monastery and its landowners. As we shall hear shortly, it was also where the papers sealing the surrender of the abbey were signed in 1538.

The chapter house was also where the election of Abbots took place. In 1533, there was a much-disputed election when the monastery’s patron accused the Office of Abbots, Edward Kirby, of maladministration of the house. An inquiry was convened involving other local Cistercian Abbots and Thomas Cromwell. Edward Kirby later resigned, being given a pension of £44 a year, a substantial sum for the time!

Subsequently, the Abbot of Rufford in Nottinghamshire, a daughter house of Rievaulx, was imposed on the abbey. The community was bitterly divided, with only eight members consenting to the legality of the election.

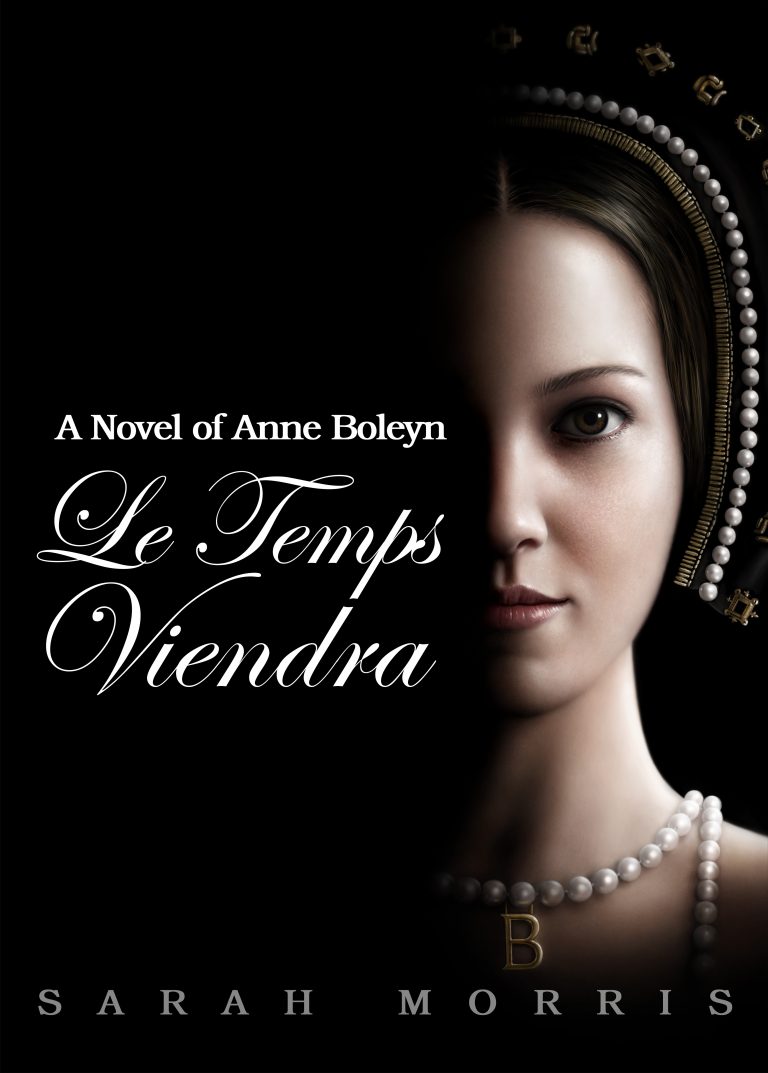

The timing of this debacle in 1533 and Thomas Cromwell’s meddling is significant. It is played out against the backdrop of the King seeking to end his marriage to Katherine of Aragon and the rising influence of early Protestants, or Evangelicals, at court.

Such Evangelicals fed Henry with the notion that monasteries were dens of papist loyalty and corruption. Although Henry remained a committed Catholic, certain aspects of the new religion suited his cause, allowing the King to free himself from the jurisdiction of the Pope and dissolve his marriage to Katherine. Despite the majority of the country being fervent Catholics, a small number of powerful influencers close to the King, such as Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell, were able to ignite the Reformation. The winds of religious change began to blow, signifying an entirely new era or a middle road, a combination of old ways and new.

As we have already heard, monasteries like Rievaulx Abbey were deeply integrated into local society. For example, the Abbey was a significant employer in the local economy. It even served as a retirement home for those who could afford the board and lodgings. Yet, momentously, on 3 December 1538, in the chapterhouse, Abbot Blyton and his 29 monks signed the paperwork that would formally dissolve Rievaulx Abbey; legally, Rievaulx ceased to exist.

The Dissolution was a savage and brutal process. Many intransigent Abbotts and monks who refused to bend to the will of the Crown were put to death in unspeakable ways. But it was not just the inhabitants of the monasteries who suffered. The monasteries themselves were savaged and stripped of their intrinsic cultural and spiritual value; treasures were looted, and the buildings were pulled down. Even John Bale, a former Carmelite monk turned devout Protestant, remarked on the Dissolution era as a ‘wicked age, much given to the destruction of things memorable.’ The violence surrounding the Dissolution of the Monasteries can be seen in the scars on the stone ruins at abbeys like Rievaulx.

The Church at Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx conforms to the layout of any Cistercian monastery, with the church being the sacred heart of the monastery. The entrance from the main cloister on its south side is paved with tombstones from high society locals. In return for their generosity as benefactors of the abbey, they sought burial within the abbey in the hope that their good deeds and burial within such a sacred place would expedite their journey to heaven.

A surviving description of the church from just after the suppression gives us a real sense of the buildings, fixtures, and fittings and how the abbey functioned. The doorway from the night stairs, still surviving in the wall of the south transept, shows where the monks would process to the church from their dormitory to sing the first service of the day at an ungodly 2 a.m.!

The soaring architecture of the church is befitting one of the most important religious buildings in Northern England. The magnificent thirteenth-century extension of the church is often said to symbolise Cistercian decadence and decline from their original austerity into the base trappings of lavish architecture. However, for the monks at Rievaulx, this was no gaudy whim; it was built to house the relics of Aelred, placed above the high altar. This shrine was put in the centre of the monastic church to display the most significant churchman of the twelfth century. Indeed, his feast day on 12 January remains part of the Roman Catholic Anglican calendar today.

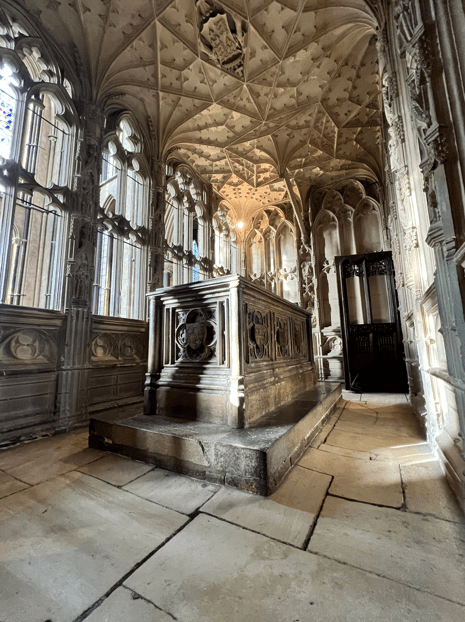

Image: Author’s own

To the right of the high altar, down 2-3 shallow steps, is the outline of an extension to the chancel. This room was once the abbey’s sacristy, where the monastery’s sacred vessels were housed; this included the altar plate, processional crosses, chalices and theroables for the incense and vestments. No records from Rievaulx speak directly to the treasures housed in its sacristy. However, surviving documents from comparable monasteries indicate that there would have been a wealth of precious metal, plate and ornately embroidered cloaks and vestments worn by the officiating clergy. Sadly, most monastic wealth was destroyed at the Dissolution. Objects were either sold or melted down, with very little surviving to this day.

The Museum at Rievaulx Abbey: Artefacts from the Dissolution of the Monasteries

The museum houses a variety of shattered remains salvaged from the Abbey ruins. These include an image of Christ the Saviour. The seated figure is a treasure of medieval sculpture but shows the unceremonious hacking and decapitation of the holy deity. Other fragments of statues and the heraldic badge of the De Ross family speak of the ferocity of the sacking of the Abbey; even the expensive and intricately hand-crafted stained glass is wrecked and remnants left behind as it was ripped from its casing to be sold or stripped for the lead.

Within the museum is a large slab of melted lead. Emblazoned on it is a Tudor rose with a crown above (see below). No one could be under any illusion that this lead, stolen from monasteries, symbolises what lay beneath the Dissolution – greed and the King’s desire for total dominance of the Tudor crown above all else.

The Epilogue: Rievaulx Abbey after the Dissolution

In the space of 4 years, all monasteries across England were dissolved. It was an act of unbelievable vandalism and a profoundly traumatic experience for all those involved. Perhaps characteristically of the brotherhood of the monks, many kept in touch after the Dissolution and remembered each other in their wills. One monk’s will read, ‘I leave to every one of my brothers who was with me at Rievaulx Abbey on the day of its disillusion [six pounds]’. Some who survived the trauma sought to continue their aesthetic lives. They tried to live out their days in small communities, including in manor houses of sympathetic aristocrats; such was the case at Coughton Court in Warwickshire.

The ascension of Henry VIII’s Catholic daughter, Queen Mary I, to the throne in 1553 brought a glimmer of hope to those who remained committed to the Catholic faith. Many former monks and nuns believed they would be restored to their former status and their homes would be rebuilt. But with Mary’s reign cut short by her death in 1558 and Elizabeth I’s ascension to the throne, the Dissolution of the Monasteries as a fait accompli was sealed once and for all.

The violence carved in Abbey ruins, and the stories of those who suffered this incredible fate endure. The tumult and ferocity of the change are borne out by the fact that more people were killed for their religious beliefs in the sixteenth century – both catholic and protestant – than in the entire history of the Spanish Inquisition. The brutal dissolution of the monasteries and what took place at Rievaulx Abbey makes this period of history forever woven into the fabric of our country’s jaded journey to religious freedom, borne out of the ashes of the men and women devoted to God and their community and one man’s determination to marry the woman he loved.

Michael’s Top 5 Abbeys:

- Rievaulx Abbey is one of the great Cistercian Abbeys of England. It is situated near Helmsley in the North York Moors National Park, North Yorkshire.

- Fountains Abbey is one of England’s largest and best-preserved ruined Cistercian monasteries. It is near Ripon in North Yorkshire.

- Blackfriars in Gloucester, founded about 1239, is one of the most complete, surviving Dominican black friaries.

- Lacock Abbey, in the village of Lacock, Wiltshire, England, was founded in the early thirteenth century by Ela, Countess of Salisbury, as an Augustinian nunnery.

- Gloucester Abbey was a Benedictine abbey in Gloucester, England. It has been Gloucester Cathedral since 1541.

Best places to see monastic artefacts

- The British Library is an excellent resource housing some beautiful books and manuscripts, including the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Sherborne Missile.

- Towneley Hall, in Barnsley, houses two magnificent fifteenth-century vestments from Whalley Abbey.

- The British Museum houses three fourteenth-century ornamental roundels called the Warden Abbey Morses.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum, lent from a Benedictine monastery and possibly from the great Benedictine monastery at Bury St. Edmonds, contains a relic tablet complete with saint’s bones and heraldry. It also contains the only surviving silver medieval monastic metalwork.

Bio: Michael Carter

Michael Carter is a senior properties historian at English Heritage. A monastic expert, he holds a doctorate from the Courtauld Institute of Art and since joining English Heritage in 2015 has worked on reinterpretation projects at Battle, Hailes, Rievaulx and Whitby. Michael’s publications include The Architecture of the Cistercians in Northern England, c.1300-1540? and he has an especial interest in English monasticism on the eve of the Reformation. He is currently books on monasteries and saints’ relics in the late Middle Ages and monastic ghost story writing.

‘It would have pitied any heart to see’: Destruction and Survival at Cistercian Monasteries in Northern England at the Dissolution by Michael Carter can be viewed online here.

Do you know the names of the remaining monks who were slaughtered at Reivaulx in 1538? Also, are their grave locations known?

Sorry Dave, I don’t know. You would need to speak to an expert like Michael Carter from English Heritage who knows everything there is to know about the Dissolution. I’ll drop him a line. See if he knows…

Michael has come back and said, no deaths at Reivaulx. Teh penultimate abbot was condemned but survived. He is sending me through some more info…