Esher Palace: Wolsey’s Refuge in Surrey

I love putting together lost Tudor buildings with notable historical events; it adds a new dimension to my ability to visualise the event as it unfolds – and I am sure you feel the same. Recently, my interest was well and truly piqued. For the first time, I read George Cavendish’s, Life of Wolsey from cover to cover.

Wow! What a fascinating read! Such detail – how could I have waited this long to gobble it up? For my co-authored book, In the Footsteps of the Six Wives, I had already written about Cawood Castle, the Episcopal Palace of the Archbishops of York, near York, where Wolsey was arrested, before being brought towards London in 1530. I thoroughly enjoyed learning about that great medieval palace of kings and archbishops and, through understanding more of the building, seeing the drama unfold in the great hall and dining chamber at Cawood.

However, having read the Life of Wolsey, my attention was grabbed by the place the cardinal sought refuge in as he fell from the King’s grace – Esher Palace. Knowing nothing about the site, I was ready to dive in and uncover the lost palace as Wolsey would have known it – and relive some of the dramatic events which unfolded there, directly after the Cardinal’s fall.

Esher Palace: A Brief History

Esher Palace was in Surrey, three miles from Hampton Court. The site’s history goes back as far as the 1040s when Tovi held the manor on behalf of Edward the Confessor. In 1245, Esher was bought by the Bishopric of Winchester. The earliest dwellings were modest; probably a hall and a chapel, used only as a stopping-off point between the Bishop’s Palace at Southwark and Winchester Cathedral; useful for the regular commute!

The first manor house, built in 1331, can be attributed to Bishop John Stratford (1323-33). Thereafter, the next bishop to significantly impact the site at Esher was Bishop Wayneflete. He was present at the wedding of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou and, in 1447, became King’s Councillor and Bishop of Winchester. During the later years of his life, he began a major building project at Esher, creating a sumptuous and fashionable house of its day. It was essentially this house that Cardinal Wolsey inherited in 1519.

Being a man of great wealth and power, Thomas Wolsey ‘persuaded’ the then bishop, Richard Fox, to give him Esher Palace in exchange for a healthy pension. Wolsey was desperate to have the property. Having bought Hampton Court in 1514, he wanted to base himself at nearby Esher, whilst he oversaw the work at Hampton Court, which, incidentally, began in January 1515. So, what of the Cardinal’s new house? What did Esher Palace look like, and exactly what transpired there?

If you read on, I will take you on a journey back to the early hours of the morning on 1 November 1529, to join a party of horsemen who have ridden post-haste from London with an urgent message from the King. But first, we need to orientate ourselves and recreate the early sixteenth century palace which awaits us…

Esher Palace: Rediscovering the Lost Buildings

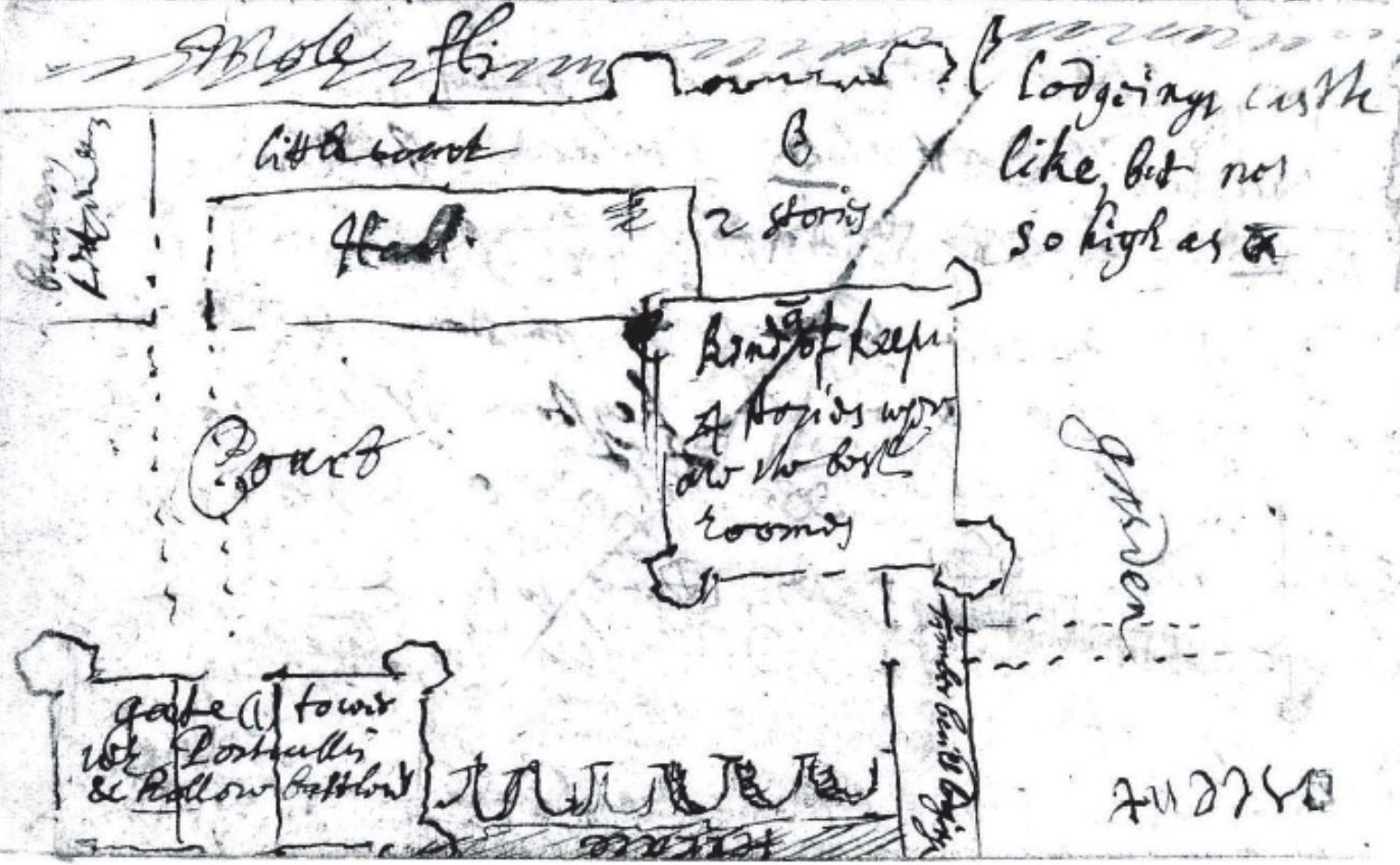

Alongside Cavendish’s contemporary account, which gives valuable insight into the lodgings at Esher Palace, there are seventeenth and eighteenth century maps, observations from time travellers through the ages, and later excavations, including the 2006 dig by Time Team, which help us piece together a fairly comprehensive picture of what Esher Palace once looked like.

Some brief notes on Esher Palace, assembled in The Natural History and Antiquities of the Country of Surrey, Volume 3, written by eighteenth century surveyor, John Aubrey, tell us that ‘at the foot of a steep hill…upon the brink of the River Mole, stands a stately strong built house of brick.’ Another survey, undertaken during the time of Edward VI (and as reported in The History of the King’s Works, Volume IV, Part II), describes the surroundings of the place, which included a garden, an orchard and a park, three miles wide. As we might expect, Wolsey’s house, close to Hampton Court, provided for that great delicacy of Tudor outdoor life – hunting.

However, one of Esher Palace’s finest features was its gatehouse, built by Bishop Wayneflete in the fifteenth century. It is the only part of this palatial complex that survives. No doubt a sweeping driveway, much as it is today, would have led the visitor to the porter’s gate. Dendrochronology, done during the Time Time dig, showed that the date range for the construction period was between 1462-72.

The gatehouse at Esher Palace is an impressive four-storey building made of red, Tudor brick, with inlaid diaper patterning, so typical of the period. Wolsey certainly emulated it when he had his gatehouse built at Hampton Court. The similarity between the two is evident. Aubrey tells how the arms of Bishop Wayneflete are ‘impaled’ with those of the See of Winchester, both above the entrance to the gatehouse and in several other places, including ‘the keystone of The Vault’.

Adjoining the gatehouse was an elevated walkway, which ran from the north side of the gatehouse to join with a narrow range of timber-built lodgings that made up the northern perimeter of the large outer courtyard, which Cavendish describes as ‘base court’.

Head through the gateway into Base Court. Directly in front of you, stood the medieval, stone-built great hall, accessed via a porch, while away to your right are the ‘timber-built lodgings’ described by John Aubrey in 1673. A 1912 excavation showed that this range was inset with windows fronting onto the courtyard; being south facing, they glint in the midday sun. Walking forward, straight ahead, and once you have traversed base court, you would have been able to dip inside the cool stone porch. This, in turn, opens up into the great hall.

Cavendish refers to the Great Hall at Esher Palace on several occasions in the Life of Wolsey, and Aubrey provides some wonderful detail of how the hall once looked; he states that it was not unlike Westminster Hall (wow!), which is thought to mean that it probably had a glorious hammer-beam roof. He also describes the several angels, carved in wood, supporting escutcheons, on two of which are scrolls inscribed with the words, Tibi Christie (Christ be with you), while several windows had painted upon them Sit Deo Gracia (Grace is God). This was quite some hall!

As would be expected, at the far end, you ‘went up’ (via some kind of staircase) to the ‘Great Chamber’. This seems to have been part of the other grand building at Esher Palace – the keep. The keep is shown clearly on the Tresswell map, being four storeys high, with towers at each corner and with parapets upon the roof. This huge tower block, or donjon, seems to have contained the high-status lodgings of the palace. In Cavendish’s account, we hear not only of the ‘Great Chamber’ but also of Wolsey’s bedchamber and other ‘chambers’ in which various visitors from the court, including the Duke of Norfolk, were invited to rest.

My guess is that somewhere close to the top of the aforementioned stairs was the ‘Great Chamber’; here, the fun begins as we can start connecting, people, events and places together. There is a detailed account of a pivotal moment in Thomas Cromwell’s life taking place in this chamber. We know there was probably a large oriel, or bay, window in the chamber, for on 31 October 1529, Cavendish comes upon Cromwell ‘leaning in the great window’ with a ‘primer in his hands…tears distilled from his eyes’.

Yes, Cromwell is crying! However, it soon turns out not to be so much for the compassion he feels towards his fallen master, the Cardinal, but for his own misfortune. He bemoans: ‘I am likely to lose all that I have toiled for all the days of my life, for doing my master true and diligent service.’ That night Cromwell leaves Esher Palace and returns to London and the court. He will come back to Esher to convey messages of the events transpiring at court to Wolsey, but Cromwell now has bigger fish to fry and is on the way up

In a recent post on the King’s Privy Gallery at Whitehall, I detailed the recycling of Wolsey’s newly-built gallery at Esher by the King, who had it dismantled and brought piecemeal to central London, where he reused it to partly construct his own privy gallery at what was then York Place. Sadly, I have not been able to find any evidence of exactly where this gallery was sited at Esher, but one supposes that logically it would have run out from the main privy lodgings in the keep, probably at first-floor level, much as was the case at The More in Hertfordshire.

Esher Palace: ‘Rumours in Retirement’

Wosley received ‘daily’ messages from the King and court during his exile at Esher. One of the visitors was Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk. Aware of the Duke’s imminent arrival, Wolsey and his servants greeted Norfolk at the gatehouse, brought him through base court, the Great Hall, and then ‘up’ to dine with the Cardinal. Thanks to Cavendish, ever-present as Wolsey’s Gentleman Usher, we know what the pair spoke about that day; it made for an interesting exchange!

Wolsey acknowledged openly that Norfolk had ‘abated [his] glory and high estate and brought it full low’, but he humbly thanked Thomas Howard for the ‘clemency’ that he had shown his ‘vanquished foe’; Wolsey having, in his own words, ‘yielded, lying prostrate before him at his feet’. The Cardinal knew he was at the mercy of those such as the Duke. Norfolk was outwardly, at least, polite and respectful in return. However, as the Duke retired to rest after dinner, Cavendish records another momentous turn of events.

A ‘Master Shelley’ arrived with a message from the King – Henry wanted York Place for himself! So it was here, in the keep at Esher Palace, that Henry VIII wrested the Cardinal’s main London residence from the See of York. However, Wolsey did not give away York Place without a degree of resistance. He gave quite a spirited defence, urging the King to set aside the law (which had declared in the king’s favour), and abide in his conscience for, protested the Cardinal, how can I ‘give away from me and my successor that which is none of mine?’ However, when Wolsey was shown the King’s commission, he yielded wisely, telling Master Shelley to ‘charge his conscience and [allow me to] discharge mine.’

Esher Palace and All Hallows’ Day, 1529

Let’s journey through the castle, from the gatehouse to Wolsey’s privy chambers. I want you to imagine a stormy night, around midnight on 1 November – All Hallows’ Day – 1529. Wolsey is in residence. Just the evening before, Thomas Cromwell had urged the cardinal to line up all his faithful servants in the Great Hall and give them the means, and permission, to leave his service should they desire – since he had nothing left to offer them. The Cardinal had been emotional, ‘lamenting the departure of his servants’, including Cromwell, who had ridden through the night to return to London and the court.

As Cavendish sleeps in his bedchamber, there is a knock at his door; he is woken by one of the porters, who tells him that ‘there are a great number of horsemen at the gate’. This is our gatehouse. Cavendish first orders that the porter takes them in and warm them by the fire as ‘it rained all that night the sorest that it did all that year beforehand.’ And yet, this does not happen immediately, for Cavendish himself puts on his dressing gown and goes to the gatehouse with all haste to demand who is there. He recognises Sir John Russell’s voice, so the mighty gates are opened, and they are ushered into the porter’s lodge on the ground floor, cold and ‘wet to the skin’. ‘Master Russell’ has been sent with a message from the King.

Cavendish must have hurried to the cardinal’s bedchamber in the dead of night. Perhaps he made his way under the covered walkway running around the perimeter of Base Court to avoid the worst of the cold wind and lashing rain, or maybe, huddled against the foul weather, he dashed across Base Court, through the Great Hall and up the newel stairs to the Cardinal’s first floor, privy lodgings in the keep. Knocking on the Cardinal’s door, he relays the message that Sir John has come with a missive from the King; Wolsey has one of his pages let Cavendish in.

Thomas Wolsey is concerned whether or not the news is good, but Sir John has already assured Master Cavendish that on his ‘fidelity’ it is, and so he commands that Sir John is brought to him. When Wolsey receives ‘Master Russell’ he is in his nightgown; Sir John reverences the Cardinal on his knees before telling Wolsey of the King’s good wishes, giving him a gold and turquoise ring as a token of the king’s affection. Henry could not quite abandon his old friend and faithful servant; for the moment, Wolsey could breathe a sigh of relief.

Esher Palace: From Christmas to Candlemas

At Christmas, Wolsey, ‘fell so sore sick that he was likely to die’, no doubt within the walls of our keep. He would rally after messages and tokens of affection were delivered to him from the King and Anne Boleyn, ‘as she was not minded to disobey the king’s earnest request’, giving the messenger a tablet of gold from her girdle belt. Wolsey lived on at Esher until ‘shortly after Candlemas’ [2 February], when he was granted a licence to live in a lodge in the Great Park at Richmond.

And so ended Wolsey’s time at Esher Palace; it had seen the Cardinal in his hour of glory and despair. With time, the palace seems to have been dismantled, with the Great Hall, the keep, the house’s main body, and the north and south sides of the quadrangle being demolished in the eighteenth century. The gatehouse alone survives in all its glory. It stands as a stalwart reminder of the great palace that witnessed the tragic decline of an ‘honest, poor man’s son’ who had given so much to his lord and master.

Additional Notes

If you would like to read about Thomas Wolsey, you can read more here.

If you want to read George Cavendish’s Life of Wolsey online for free, click here.

The gatehouse was recently up for rent, if you want to see some internal pictures of Wayneflete’s Tower today, click here.

Brilliant-loved learning more about Esher! Thank you! I was so taken by the gatehouses similarities to Hampton Court.

Thought this article may have info on the title of an old print I have ” Wolsey’s well at Esher, Surrey – ” Drawn by D.T.Harding”. – No luck unfortunately !

Somewhere on this earth -I hope, there exists a magnificent, early C19th doll’s house called ‘Grimston Garth’. This is, in fact, an exact replica of ‘Wayneflete’s Tower’ as it existed after William Kent’s house had been demolished. The doll’s house was, for many years, in the collection of Vivien Greene, at Iffley, near Oxford. After she did the collection was sold off piecemeal by Bonhams, in 1998. There are pictures of it in several of her books on doll’s houses. I wish I knew where it was now.

Wolsey’s Well is an C18th ‘folly’ installed by the Pelhams of Claremont and Esher Place (Wayneflete) to provide water to passing travellers. Nothing to do with the cardinal at all. They named it after him as a sort of historical nod in his direction.

Thanks for posting! I wonder about that doll’s house…