A Long Weekend Away in Tudor Derbyshire & South Yorkshire

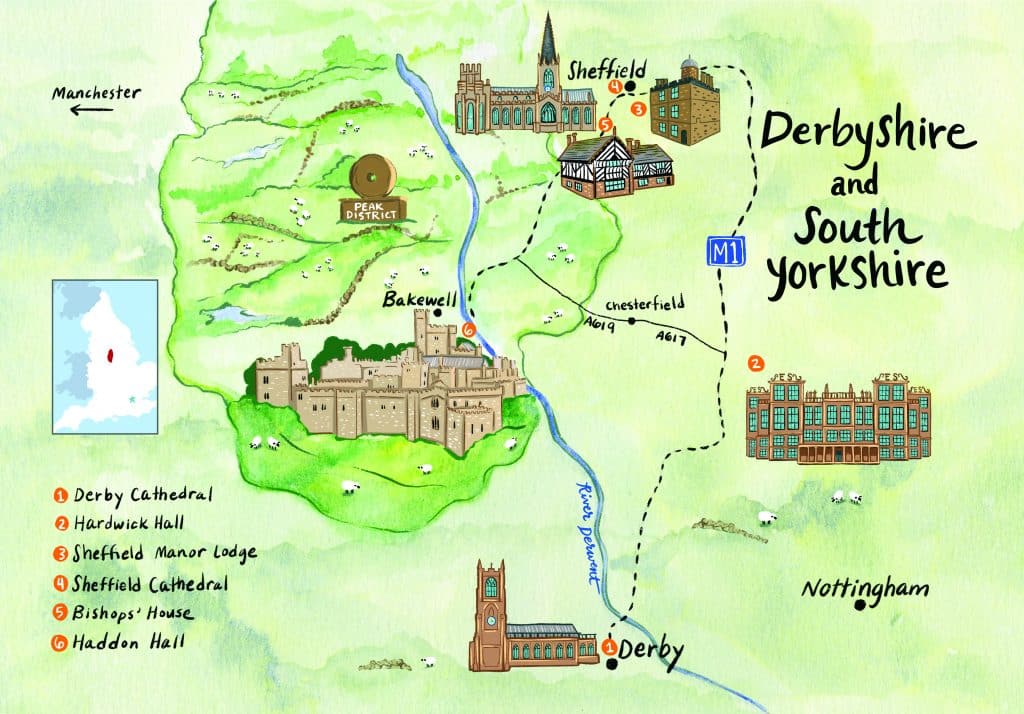

In this guide, we travel to Derbyshire and just over the county border into South Yorkshire to visit Sheffield as we go on the trail of one of the most powerful families of the Tudor age: The Shrewsburys.

The Earls of Shrewsbury were at the heart of Tudor intrigue throughout the sixteenth century. This long weekend itinerary explores two Shrewsbury properties, Hardwick Hall and Sheffield Manor Lodge. We will admire three magnificent tombs; those of the 4th and 6th Earls and the latter’s indomitable wife, Bess of Hardwick, before we round off our trip with a visit to Haddon Hall, a glorious medieval and Tudor time capsule in the heart of the Derbyshire Dales.

So, let’s get going!

Day One:

Derby Cathedral, Derby

We start our Tudor journey in Derby. This small city is not on the usual tourist trail. However, one Tudor artefact related to a doyenne of the Tudor age will draw you there: the tomb of Bess of Hardwick.

I will talk more of Bess’ extraordinary life a little later on, but for now, suffice to say that Bess was born at Hardwick Old Hall around 1520/21. She is best known for dying one of the shrewdest and wealthiest women in England, thanks to four marriages and outwitting – and outliving – each of her husbands in turn.

After Bess died at Hardwick Hall on 13 February 1607, she was interred in a vault beneath the floor of All Saints Church. Although it is now a Cathedral, in Bess’ day, it was Derby’s parish church, which explains its modest size and appearance.

A little like Sheffield Cathedral (which we will come to shortly), the present iteration is a mish-mash of architectural styles. The front tower is Tudor in origin (dated circa 1530), while the interior is of the eighteenth century and was constructed to a Neo-Classical design in 1725.

The Cavendish ‘area’, where you will find Bess of Hardwick’s monument, lies to the right of the nave, in a part of the old, medieval church known as St Katherine’s Quire. Bess’ tomb is undoubtedly one of the treasures of the cathedral. However, although her glorious funerary monument is above ground, her body is entombed in the vault below, along with a staggering 43 of her Cavendish descendants!

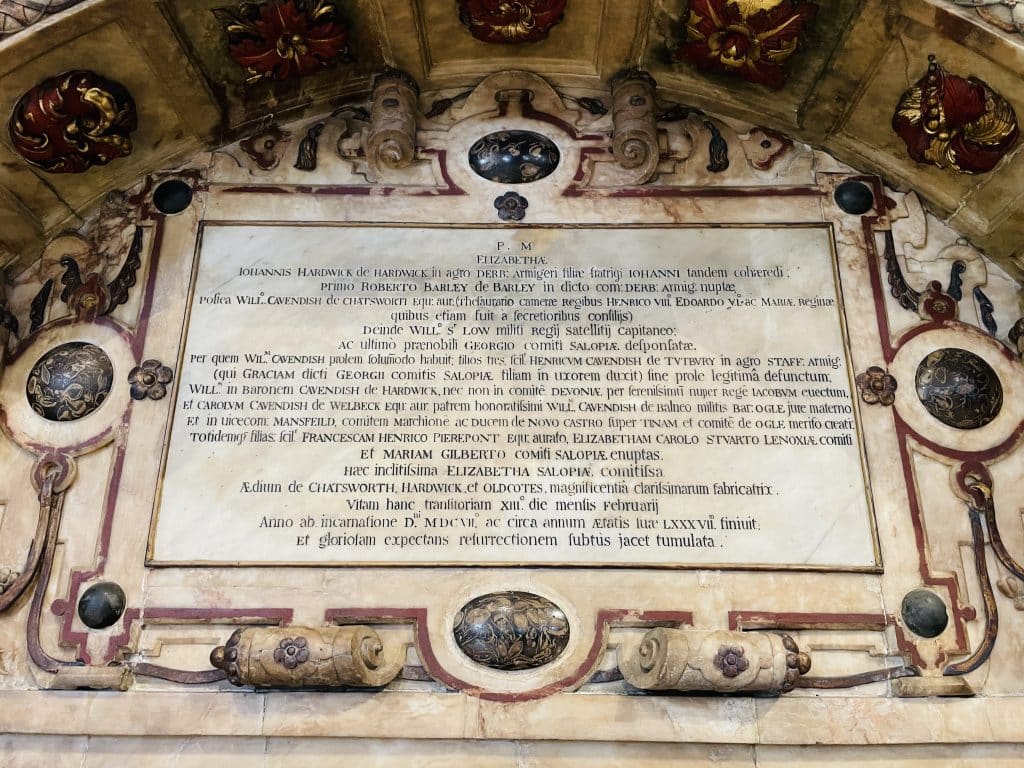

You will find her effigy lying recumbent in her state robes and wearing a coronet upon her head. Sited centrally is a carved marble tablet with her epitaph written in Latin. This retells her extensive marital history and her legacy as the foundress of three great Elizabethan houses in the area: Chatsworth (survives, although significantly altered), Hardwick (survives largely unaltered) and Oldcotes (now lost).

Derby Cathedral is in the Cathedral Quarter, right in the city’s heart and about a 20-minute walk from Derby central railway station. If you are travelling by car, there is easy parking close to the cathedral, both on the roads adjacent to it and in nearby car parks – although you will pay to park in both instances.

If you wish to read more about Bess’ tomb, click here.

Hardwick Hall, Derbyshire

Having visited Bess’ tomb, there is only one place to head for next: the legendary Hardwick Hall. If ever a building embodied the power and ambition of one person, it has to be the so-called ‘new’ house at Hardwick. The Hall indeed is one of the finest examples of a surviving Elizabethan Prodigy house in England. However, the reputation of its formidable foundress, Bess of Hardwick, intrigues the visitor as much, if not more so, than the house itself.

Elizabeth (Bess) Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, was remarkable. Born around 1520-21 at Old Hardwick Hall, she was the daughter of a landed gentry family, and as such, she had a comfortable but modest beginning. Four subsequent and advantageous marriages ensured that Bess amassed a burgeoning fortune until she became the most wealthy and powerful woman in Tudor England, next to Elizabeth I.

Before any visit to the hall, I urge you to acquaint yourself with Bess’s story, which is far too long and fascinating to reduce to a couple of sentences here. Yet, if we wish to understand the origins of Hardwick, we must understand Bess’ eventful life. For it is through the end of an increasingly acrimonious marriage to George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (her fourth husband) that Hardwick Hall emerged.

As we have seen from her epitaph in Derby Cathedral, the Countess was a prodigious builder of grand properties. Having been expelled by her husband from one of the Shrewsbury’s principal residences, Chatsworth, Bess began rebuilding the Old Hall. In doing so, she obliterated the house in which she was born. What remains in its place is a mid-Tudor house that predates the ‘new’ Hall (standing very close by) by a mere 30 or 40 years.

Although the Old Hall was eventually displaced as Bess’s residence following the completion of her stately, new home, the Old Hall remained in use, probably until the mid-seventeenth century.

Today, the ruins of the Old Hall are cared for by English Heritage. They are investing heavily in restoring the building and inserting viewing galleries that will allow access to the upper floors and no doubt, will open up some splendid views of the surviving architectural features.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the ‘new’ Hardwick Hall.

Bess’ dynastic jewel in the Crown is an impressive sight, perched high upon an escarpment, majestically holding court across the Derbyshire countryside. Above average in height, Hardwick Hall towers into the skyline with a pleasing symmetry that was so typical of great Elizabeth houses of the age. However, the windows of Hardwick are legendary: Hardwick Hall, more glass the wall’ as the saying goes. But not all of Bess’ contemporaries were impressed by or appreciated this new-fangled architectural development.

The Elizabethan Lord Chancellor of England, Francis Bacon, famously admonished such prodigy houses as being ‘sometimes…so full of glass, that one cannot tell where to become, to be out of the sun or cold.’ His point was that houses should be ‘lived in and not looked on’. On this count, Hardwick can most certainly stand accused, as some of its many windows are either blocked up on the inside or stretch, inconveniently, over two floors!

Yet, despite Elizabethan nay-sayers like Lord Bacon, Hardwick is celebrated as being an excellent example of its type, largely unmolested by the passage of time. This is certainly true of the exterior, where Bess has ‘branded’ the house atop each of its six towers with her initials ‘ES’, surmounted by her coronet.

However, some historians contend that this authenticity does not hold up in quite the same way regarding Hardwick’s interiors. They argue that subsequent owners have changed those interiors over the centuries. Even if this is the case, many fine Elizabeth features can still be enjoyed including the Hall, Bess’ Presence Chamber, the Long Gallery and numerous bedrooms, such as the Mary, Queen of Scots room (although please note, Mary’s presence in the house is a long and often romanticized legend that cannot be true, since the queen had been dead for four years before building work at Hardwick began).

The other architectural feature worth noting is the arrangement of the Hall. At Hardwick, we see a step-change development in the hall’s function – and hence its arrangement. Gone is the lengthways orientation that is seen in medieval and early Tudor halls, with the obvious low and ‘high ends’, a dais and an oriel window lighting it.

These early halls were used for living in. Hardwick’s Hall is one of the earliest examples of a hall turned about to run across the width of the building. It is lit at each end and not along the sides. Furthermore, you will notice that there is no clearly defined ‘high end’ and there was possibly never a dias. This marks a significant change in the use of great halls from spaces used for living in to the hall functioning simply as a vestibule, which is seen abundantly in the later seventeenth and eighteenth-century country houses.

The National Trust owns Hardwick Hall. When I visited Hardwick in the height of summer, sadly, the first-floor apartments, containing Bess’ private rooms, were not open to the public. This was on account of volunteer shortages. It is sad to see this is the case but underlines how important it is that we all get behind supporting these incredible heritage buildings and the work of organisations like the National Trust.

I strongly recommend you check the website or call ahead if there is anything specific you wish to see to avoid disappointment.

Hardwick Old Hall website.

Hardwick Hall website.

Day Two:

Sheffield Cathedral

Having been immersed in the eventful life of Bess of Hardwick, on this second day, it is time to ‘meet’ her erstwhile fourth husband: George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury.

Talbot came to prominence during the Elizabethan age and alongside his notorious dealings with his wife, is perhaps most famously known as the long-time gaoler of Mary, Queen of Scots, who remained in Talbot’s custody for nearly 15 years from 1569-1584. During this time, she was moved between Shrewsbury’s principal residences of Sheffield Castle, Wingfield Hall, Tutbury Castle, Hardwick Old Hall, Chatsworth, Buxton and Sheffield Manor Lodge.

By 1580, the Shrewsbury’s marriage was breaking down. A complex set of circumstances, including a deterioration in Shrewsbury’s mental state, were to blame. Bess and Talbot were separated during the final few years of the Earl’s life, with Talbot taking his housekeeper as his mistress and companion. He blamed Bess for their differences and wrote with vitriol that she was his ‘wicked and malicious wife’ and ‘my professed’ enemy.

George Talbot died in Sheffield in 1590. His funerary monument is located in the Shrewsbury Chapel, within the oldest (medieval) part of Sheffield Cathedral.

The chapel can be found at the east end of the church to the right of the high altar. It was added to the then parish church in 1520 by the 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, George’s grandfather. The two Earls lie in repose opposite one another, although the vault intended to take their bodies lies beneath the floor, accessed by a set of steps, buried just in front of the chapel.

Talbot’s tomb is of typical late Elizabethan design, blending classical architecture with early English sepulchral elements. Most eye-catching of all is Talbot’s marble effigy. The Earl is recumbent in a full suit of armour with his helmet placed close to his head. Sited centrally, above his marble effigy, is a tablet engraved with a long Latin inscription. If you can read Latin, you will notice there is no mention of his despised wife!

Sheffield Manor Lodge

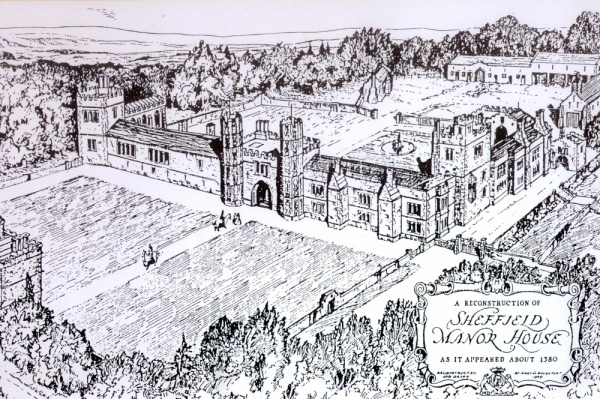

Sheffield Manor Lodge was once a grand Tudor manor house, fashioned from the remodelling and augmentation of a pre-existing hunting lodge. The creation of this early Tudor manor house was likely undertaken by another George Talbot, this time the 4th Earl of Shrewsbury. It was probably completed before 1516, with the newly renovated house being one of two principal residences of the Shrewsbury family in Sheffield; the other being the now entirely lost castle.

Sheffield Manor Lodge was perched on an elevated promontory of land overlooking Sheffield Park, which was one of the country’s largest at around 2500 acres. The park provided income and fine pastime for the Earl of Shrewsbury, his family and guests, while a much-celebrated avenue of walnut trees connected the manor directly with Sheffield Castle. Today, the city is sprawling. Its later history saw it thrive in the industrial age as a steel producer. Therefore, such natural beauty is hard to envisage. However, it surely must have made for a pleasant, leafy highway for the Earl and Countess to ride between two of their favourite principal residences.

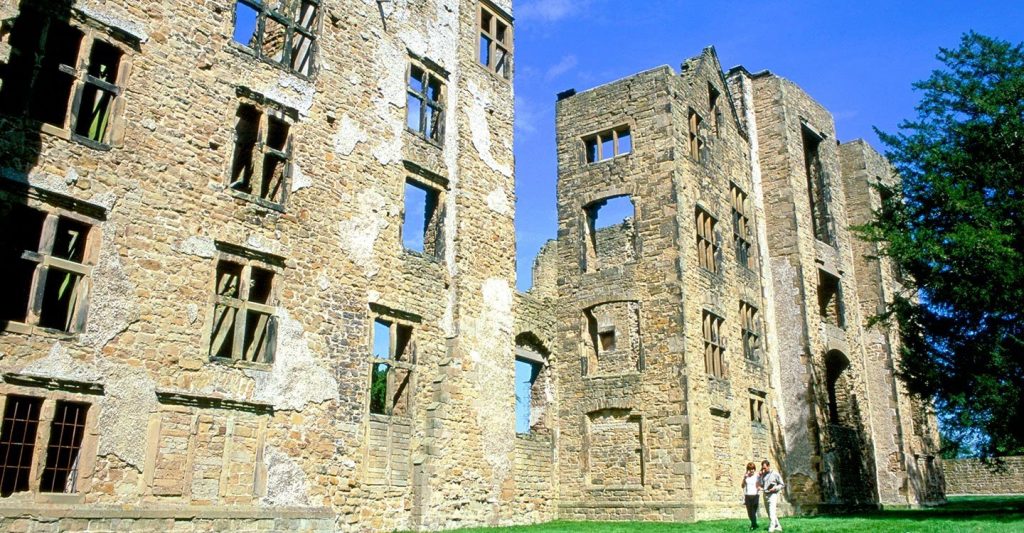

If we wish to recreate the house as it looked in its heyday, we must imagine a property made of brick and timber and arranged fashionably around two courtyards: an Outer or Great Court and an Inner one.

The Great Court was almost entirely square and covered two acres. An inner gateway flanked by two octagonal, red-bricked towers gave access to a smaller inner courtyard.

One of the most treasured accounts of the layout of the house comes from George Cavendish, Gentleman Usher to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who the 4th Earl received on his sorry progress south following his arrest at Cawood Castle in North Yorkshire in November 1531. You can read more about the Cardinal’s time at Sheffield Manor here.

Cavendish’s remembrances of his master speak of this inner gatehouse, which contained a ‘noble flight of steps’ leading up to a door that opened into the Great Gallery. This is where Wolsey was housed during his 18-day stay at the Lodge. Cavendish helpfully describes how the Cardinal was led to a ‘fair chamber at the end of a goodly gallery, within a new tower.’ Shrewsbury had the gallery temporarily partitioned off by a ‘traverse of sarcenet’ (a soft silk material), which had been placed across the middle of this large chamber. In doing so, Cavendish states: ‘one part was preserved for my lord and the other part for the earl’.

The scant above-ground remains of this once great house and later archaeological excavations allow us to pinpoint the exact position of the gallery. This ran north-south, fronting the Great Court on one side and the Inner Court on the other. The tower mentioned in Cavendish’s account was at the northern end of the gallery mentioned above. In these rooms, Wolsey was lavishly housed and lacked for nothing.

If you visit today, you will see the gallery’s west wall, including a series of stone window frames typical of the period, the ruined tower and even the lavatory where surely Wolsey spent some agonising hours after falling ill over dinner one evening. It was the onset of an illness that would cost him his life. He died several days later at Leicester Abbey on 29 November 1531.

Of course, another perhaps even more famous prisoner to stay at Sheffield Manor Lodge under the custody of the 6th Earl and his wife, Bess of Hardwick, was Mary, Queen of Scots. As I have already mentioned, Mary was no transitory guest. She stayed with the Cavendishes for nearly 15 years, being moved from one Shrewsbury residence to the other. We know that she was lodged for some time at Sheffield Manor Lodge. Unfortunately, the location of her rooms has been lost to time.

However, if you visit today, you will be able to enjoy the Turret House, also known as ‘Queen Mary’s Tower’. The tower is complete, and one of the rooms on the upper floor contains a fine, moulded plaster ceiling from the sixteenth century. It is believed that this may have been co-designed by Mary. It certainly leaves the visitor with a lingering sense of the grandeur of the Shrewsbury’s lost home.

Sheffield Manor Lodge is only open during the summer on Sundays when guided tours run onsite. It is also open during February and October half-term holidays and for special events. Check out the website for all the latest information.

The Bishop’s House, Sheffield

On another note, if you have time, you might consider visiting The Bishop’s House on the edge of Meersbrook Park, which was built in 1554. According to the website, the house ‘appears to be the last surviving building from that time of Norton Lees. Norton Lees was then a tiny village surrounded by fields of the Derbyshire countryside, with Sheffield a small town some two miles away.’

Today, it is a wonderful museum of Tudor life and a delightful find. What is more, entry is free, and you will likely enjoy a wealth of information from one of the Friends of Bishops House, who manages the building alongside Sheffield City Council. The House is only open at weekends. Do check out the website for opening times.

Day Three:

Haddon Hall

If you have never visited Haddon Hall before and you love medieval architecture, then you are in for a treat. According to Architectural Historian, Anthony Emery, Haddon is simply renowned for being ‘among the leading late Plantagenet survivals in England’.

Perched upon a rocky outcrop of land above the River Wye, its imperious majesty is awe-inspiring as you approach via the outer gatehouse and across a pretty stone bridge. In fact, you are looking at what was once the rear of the Hall. At some point, the main entrance was switched from East to West. This makes for a rather awkward approach up a short steep incline into what is now the outer courtyard.

At its core, Haddon Hall is a fourteenth century hall house, with its great hall in the current cross range, a parlour leading off the high end and a wonderfully preserved screens and kitchen passage off its low end. This passage leads the visitor into one of the best-preserved medieval kitchens you are likely to see anywhere. The work surfaces are worn by centuries of grinding, cutting and slicing; the stone floor leading from the kitchen to the Great Hall is eroded by generations of servants scurrying back and forth.

Haddon is truly a time capsule!

Over the next three centuries, Haddon was progressively augmented. It is particularly noted for its fifteenth century architecture. Once again, quoting Emery, these fifteenth century details are ‘finely preserved and greater in number than anywhere else in England’. However, for me, its pièce de résistance is the early seventeenth century long gallery. It ranks as one of my personal favourites. With its large lightsome windows and pale oak panelling, it is both elegant and inviting. No doubt, you will recognise it as it has featured in many a period costume drama!

Thanks to its abandonment by the Vernon family (later the Dukes of Rutland) in the seventeenth century, the building passed into a deep slumber for around 200 years. Therefore, mercifully, it was unmolested by well-meaning Georgian and Victorian generations of the family, seeking to update and modernise the family home. When it was finally restored in the early twentieth century by Lord Granby, the eldest son of the 8th Duke of Rutland, it was done so carefully and sympathetically, such that when you visit Haddon today, it is truly like stepping back in time.

One of the highlights of the calendar at Haddon Hall is its annual Mercantum Christmas Fair. Over three extended weekends, usually in mid-late November and early December, the house is joyfully decorated for Christmas, and an army of craftsmen and women descend upon the Hall. The courtyards, rooms, gallery and gardens are packed with stalls overflowing with enticing Christmas gifts. At the same time, a giant Christmas tree and tasteful decorations deck the Great Hall and each of its chambers.

There are so many things to entice, but when you are done shopping, you can enjoy a stroll around the garden with a steaming cup of mulled wine in your hands and take in the stunning views from the garden terraces across the Derbyshire countryside.

There are so many reasons to love Haddon Hall. It is a must for anyone who loves Medieval and Tudor architecture or enjoys their Tudor places unspoilt by the passage of time. It might be last on our list of Tudor places to explore this week – but it is by certainly no means the least!

Note: There is a restaurant on-site at Haddon Hall. However, if you wish to treat yourself to a touch of luxury and fine dining, Lord and Lady Edward Manners, who own and reside at Haddon Hall, run the nearby Peakcock at Rowsley. The Peacock has four-star accommodation and a Michelin starred-restaurant. Needless to say, booking is essential.

One Comment