The Palace of Collyweston: The Incredible Hunt for a Lost Tudor Power-House

The Palace of Collyweston has become nothing short of the stuff of legend. This was an extensive Tudor palace favoured by the invincible Margaret Beaufort. It was visited by Henry VII, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, and it was also where a sad farewell was made to the 13-year-old Margaret Tudor as she progressed north to take up her position as Queen of Scots.

Tragically, the palace is now completely lost. So much so that its exact position and extent are no longer known. To rectify this sad state of affairs, in the summer of 2019, the local Collyweston Historical & Preservation Society began an archaeological project to try and answer just these questions.

I visited the site that summer as the first trenches were being opened in the garden of an enthusiastic resident. In the first part of this blog, we revisit the conversation I had at the time with the President of the Collyweston Historical Society, Chris Close, and researcher, Sandra Johnson.

In the second part of the blog, I will update you with the latest news that, finally, after much searching, it seems as though the precise location of the palace has finally been uncovered! This is a thrilling discovery and heralds the beginning of a new chapter in our understanding of one of the great powerhouses of the Tudor age.

Both the original blog and the most recent updates are accompanied by podcast episodes. Links to these episodes are included at the end of the text. Before we come to my conversation with Chris, let’s fill in some of the gaps with an introduction to the history of the Palace of Collyweston and a little bit more background information that I was able to unearth on this once great Tudor palace.

The Palace of Collyweston – a Brief History

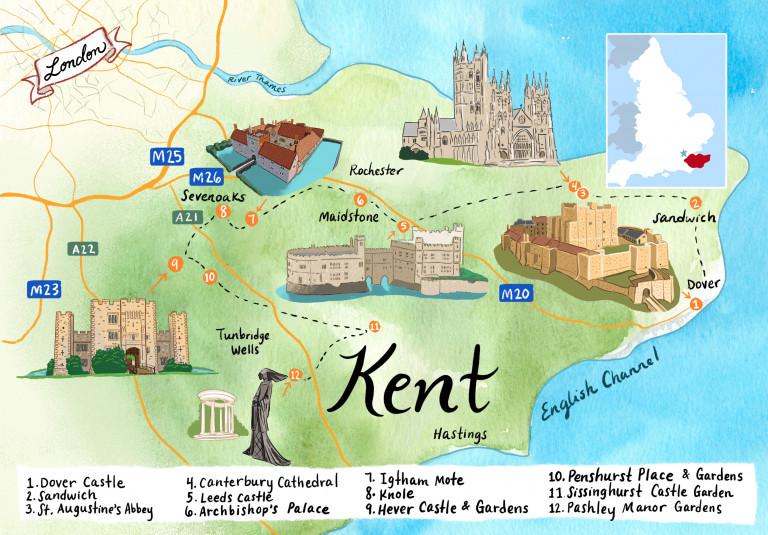

Collyweston, in Northamptonshire, is a quintessential sleepy English village, with an old-fashioned village sign, medieval parish church and obligatory pub. It lies not far from Stamford, which, in days gone by, straddled the old North Road. This was THE major, medieval route between London and the North of England during the Tudor period. This made it a critical strategic settlement and stopping-off point for travellers. This included kings and their retinues.

But once upon a time, the Palace of Collyweston was a centre of power, a royal manor house, aggrandised by its first Tudor owner, Margaret Beaufort. Under Lady Margaret’s ownership, Collyweston became the administrative centre for the Midlands, as we shall shortly hear.

It was visited by Henry VII, Henry VIII, Catherine Howard and Elizabeth I. Yet, a little over 150 years after its heyday, the house was dismantled and irrevocably lost, except for enduring earthworks in the ground.

Although there were earlier owners, the history of the manor at Collyweston seems to get underway around 1415, when Sir William Porter bought it. He was a man of humble origin who, by loyal service to the Crown, a favourable marriage, and no doubt a good deal of schmoozing, became very wealthy indeed. Porter may have carried out building work at the manor house.

Its second owner was Ralph, Lord Cromwell (also responsible for building Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire), who bought the house after Porter died in 1436. He lived in the house and died there in 1455.

By 1459, Collyweston had come into the hands of the Earl of Warwick, ‘The Kingmaker’ and thence to his daughter, who married George, Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV. Clarence became the first royal owner of the manor and may have also added to the house. After he was executed on his brother’s orders in 1478, Collyweston became the property of the Crown.

However, it was after the Battle of Bosworth, when the Tudors ascended the throne, that the manor became most well known. In 1486, it was given to Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond, the King’s mother, for life. She had spent much of her youth with her mother and step-siblings at Maxey Castle in Cambridgeshire, some 10-11 miles to the east. So, she may well have had fond memories and deep emotional ties to the region.

We know from John Leland’s Itinerary that Margaret extended the palace – ‘for the moste parte … a new building by Lady Margaret, mother to Henry the vijth.’ Around 1500, she altered and enlarged the house and improved the park and gardens adjoining the manor.

Then, in July 1503, Margaret hosted her son and court at Collyweston. The recently widowed King had travelled from Richmond Palace with his 13-year-old daughter, the new Queen of Scotland. She would leave her father behind at the Palace of Collyweston, and as a parting gift, he gave her a personally inscribed Book of Hours. The inscription reads: ‘Remember yr kynde and loving fader in yr prayers – Henry R‘ and ‘Pray for yr lowving fader that gave you this boke and I gyve you at alle tymes godd’s blessyng and myne. Henry R.

Given the very recent death of Elizabeth of York, emotions must have been running high; to effectively lose both a mother and father within a space of a few months must have been particularly traumatic for the teenage princess.

Some 20 or so years later, Henry VIII bestowed the manor on his illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy. There is an incredibly touching insight into one moment in time at Collyweston, when a certain five-year-old boy, called William Cecil (the future Lord Burghley), was sent to join the household of Fitzroy, who was en route to Sheriff Hutton in North Yorkshire. To think what life lay ahead of that small child! Of course, he would eventually become one of the most influential men in Elizabethan England, being Elizabeth I’s ‘strength and stay’ from her accession in 1558 to his death in 1598.

As mentioned, Henry VIII himself lodged at Collyweston five years after Fitzroy’s death, between 2-5 August 1541. Catherine Howard was alongside him on that fateful progress, which was, of course, to be her last. Finally, from a Tudor lover’s point of view, the final royal owner was Elizabeth I, who was granted it by her brother, Edward VI, in 1550, when she was still a princess. Elizabeth would only visit once, though, in 1566, during the course of a Midlands progress.

The Appearance of the Palace

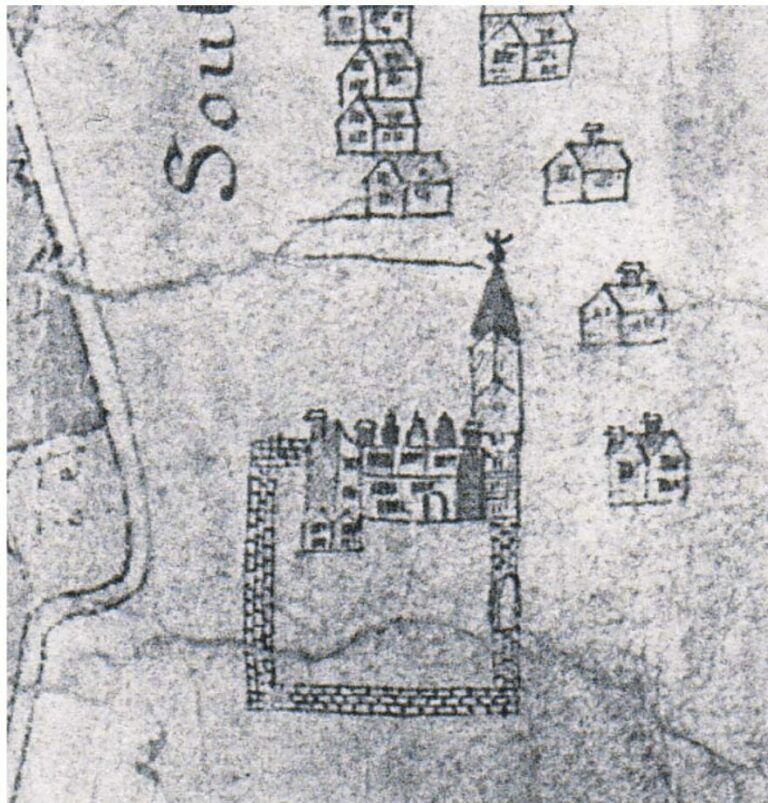

Sadly, there are no extant images or plans of the palace. Accounts describe an ‘outward’ court, in which a ‘great walnut tree’ was noted to grow during the Tudor era; by deduction, this suggests that there was also an ‘inward court’. Thus, we have at least a two-courtyard house. In fact, the most recent research has revealed that Colyweston was a three-courtyard palace.

From the account of The Clerk of the Works for the Lady Margaret, we are given insight into an inventory of the rooms at Collyweston. They were: the chapel, the library [a very high-status feature, and extremely rare at the time], the scalding house, the new chamber over the gate, the spicery, the vestry, the brewery, the bakehouse, the chamber over my Lady Bray’s chamber, the pastry, the counting-house, the clock house in the great tower, the kitchen, the wet larder, the queen’s chamber, the wardrobe of the beds, the clerk of the kitchen’s chamber, Henry Clegge and Whytyngton’s chamber, the great parlour and the well beside the bakehouse.’

As one might expect of a high-status house of the period, there was a gatehouse, a great hall and a chapel. However, later Elizabethan accounts also speak of a ‘gallery going out of the hall’, while buttresses are mentioned, suggesting a stone building. Then, in preparation for the 1566 visit by Elizabeth I, we hear of a timber banqueting house that was constructed, ‘having windows with casements and ‘lettys’; this structure was approached via a stone staircase.’ William Camden noted in 1607 that the Palace of Collyweston was ‘handsome and elegant’.

The Ruin of the Palace of Collyweston

In September 1737, William Stukeley, an antiquarian on his travels through England, rode through Collyweston and saw ‘My Tyron’s house, the royal palace of Henry VII’s mother, Margaret, Countess of Richmond’. In the notes, he adds that the royal palace once existed where ‘Mr Tyron’s stackyard is’ and that within living memory there was ‘a great hall, a tower, a dungeon [can mean ‘keep’ or ‘donjon’ where the principal apartments were sited], and a kitchen with four chimneys.’ However, by 1780-82, all the ‘materials’ from the old manor were finally removed, leaving only earthworks, garden terraces, two fishponds and park boundary banks as clues that a majestic property ever existed in this pretty corner of the Northamptonshire countryside.

As a supplement to the interview recorded for The Tudor History & Travel Show, I also spoke with Sandra Johnson from the Collyweston Historical & Preservation Society. Sandra has researched the palace, so I was keen to hear more…

Interview: Collyweston in the Records

Sarah: So Sandra, we have heard from Chris that the actual location of the palace isn’t known, but what do we know about the palace itself, particularly its appearance?

Sandra: It was pretty significant. In fact, it was a vast building. We know it had two courtyards, and potentially three, because Margaret Beaufort added to it, notably for the arrival of the wedding procession of Margaret Tudor in 1503. We know that she had Jewel Tower. She also had a Counting House. So, apart from her jewels, she clearly had lots of money! You see, Margaret Beaufort administered the Midlands from Collyweston. This meant that there was also a council chamber where she could conduct business – quite unusual for a woman!

Sarah: So, Margaret actually administered the whole of the area in the Midlands on behalf of her son Henry VII?

Sandra: She did, yes. She was one of the very few women who could conduct business in her own right – [known as a ‘femme sole‘]. She, therefore, administered her estate independently. Very few women in the Middle Ages were allowed to do that. I think Alice Chaucer was another one. So, she had power, and on behalf of her son, she could intervene where there were disputes. People would probably come over from Coventry or somewhere similar to Collyweston for her to adjudicate on whatever was under question – and she would decide guilt or innocence – and the sentence.

Sarah: It’s fascinating that Collyweston had its council chamber like other grand palaces!

Sandra: Of course, there was also business to be done locally, in the village and the surrounding areas; she would have collected the rents because the villagers would have paid money for the rent of lands or other taxes. So, yes, Lady Margaret was very influential in the whole area – and Collyweston was one of her favourite places.

Sarah: Do we know how long she spent here in the palace?

Sandra: Like all royals, she, no doubt, tended to live in a palace until it was a bit smelly and horrible, and then they moved on somewhere else. So Margaret progressed around the country to other areas as well. She frequently followed the King’s progress closely because she was very keen on court etiquette and telling people what to do and how to behave – particularly her daughter-in-law! But she did indeed spend a good deal of time at Collyweston.

During Margaret Tudor’s progress towards Scotland to become the Scottish Queen, the royal family stayed at Collyweston for quite some time. After Margaret had waved goodbye to her family, the King stayed on for another two or three weeks.

Sarah: Do we know anything of those celebrations in the records? Are there details of what happened during those weeks at Collyweston?

Sandra: We know they were trumpeters, and there are details of the Lords that actually escorted Margaret Tudor on her journey. We know that she rode on a white palfrey and that they took the whole household with them. So there were many people here, and it was a grand procession. At each entry into the next town, the trumpeters would announce that the royal party was coming. And it was the same with Henry VIII when he came here on progress with his then-wife, Catherine Howard.

Sarah: This was part of the 1541 progress following the uprising in the north? ‘The Pilgrimage of Grace’ as it came to be known.

Sandra: Yes. He had an army with him. So, we might deduce that they must have camped around the palace. But the description of what they brought is astonishing: furniture, furnishings, jewellery and crockery. It was like having a portable house!

You know, there could have been some 200 or 300 people, just in the king’s retinue, plus the ‘also-rans’ that were camped around – in case they’re needed to fight off the locals! And indeed, when it was the royal wedding, they had to put people up in other villages. So, some of the courtiers would have been lodged in nearby Stamford. At any one time, Margaret had 200 to 400 people living in the palace as part of her household.

Sarah: So, this gives us an idea of the scale of the place in comparison with Henry VIII’s great houses, which were, by definition, houses that could hold the whole court of usually around 1000 people. So we’re talking a little under half the size, but still, that’s still a big household.

Sandra: Yes, it’s still a big house. I think an average household, apart from when she had visitors, was about 200. She also had quite a substantial choir; there are records of around 24 surplisses for men and 19 for boys.

Sarah: Can you explain what they are? ‘Surplisses’?

Sandra: It’s the loose, white linen vestment worn over a cassock. Margaret had a choir come over from Fotheringhay to sing here. We know she had a little glade and her choir would sing in the glade, which was adjacent to the fish ponds.

Sarah: When did the history of the house start? What do we know of its early owners?

Sandra: William Porter was the first noble to live in Collyweston. Before that, it was owned by various other people, but none of them actually lived here. Porter lived here and built a manor house. Ralph, Lord Cromwell then acquired that house after Porter’s death and either knocked it down or possibly adapted what was here to build something a little grander. However, he did take off a doorway and had it installed as the main doorway into the parish church. You can still see that today.

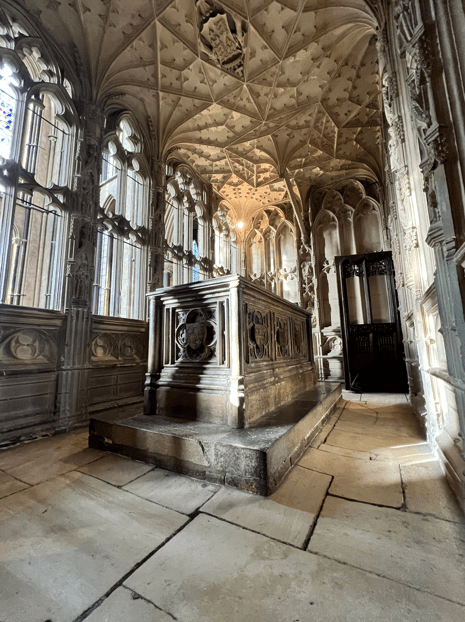

There is also the chapel adjoining the parish church that Margaret Beaufort built. There is a squint in the chapel, which is angled so that she could see the priest, but the villagers couldn’t see her. Sadly, though, there’s nothing there that relates to Margaret Beaufort.

Looking at the church on the outside, it’s quite ‘rubbley’. It was obviously put together quite quickly, and it’s not made of fine stone. So we presume that her chapel and the palace here at Collyweston were so grand that she didn’t need to make her mark in the rest of the village.

Sarah: Speaking of chapels, she had a chapel on-site in the palace, didn’t she? We know that Lady Margaret was famously religious, and you’ve already indicated that the chapel must have been quite a size by the number of surplisses. Do we know anything about how her private apartments adjoined with the chapel?

Sandra: I think one end of the private apartments joined the chapel, and the other would have joined the great hall. She had four great bay windows facing out across the Welland Valley, so they looked out in a westerly direction. Whether they were all in her private apartments or whether there were separate lodgings reserved for when the King came, we are not sure.

But at Christ College in Cambridge, the master’s rooms were built simultaneously or just after Margaret Beaufort died. So, John Fisher, her confidante, was very instrumental in what she had here and what she had there. So, it’s pretty likely that Christ’s College Chapel and the room attached to the chapel were similar to what was at Collyweston. We also know that she didn’t have a squint at Christ’s College; she had a bay window so she could look down into the body of the church to observe the service. We believe she would’ve probably had one here, too, at Collyweston.

Sarah: I wouldn’t have expected any less of Lady Margaret! Well, thank you very much for giving us an insight into what we know about the fascinating Palace of Collyweston!

Collyweston Palace: Found!

After an absence of four years, I returned to Collyweston this Autumn (2023) to hear the latest update in the search for Margarer’s Tudor palace. Little by little, the project has gained traction (and therefore funding!) over the last four years, culminating in a full geophysical survey (conducted by John Gater of Time Team fame) of the site on a scale that has not been possible before now.

The results have been spectacular! When I received a message from Chris Close that the palace structures had ‘lit up’, I couldn’t wait to learn more. So, on a cold, damp, misty November morning, I met with Chris in the village to find out all the latest. Together, we toured part of the palace’s perimeter, and Chris showed me the LIDAR scan (and the current best guess as to what the scan shows).

These guesses are based not only on the outline of the buildings that have been revealed but are also a result of drawing upon written sources that detail the relative position of particular structures in relation to others. Chris stressed that this plan is just the starting point. The next phase, commencing in 2024, will be an archaeological investigation of the site in partnership with The University of York and Historic Royal Palaces.

If you want to hear the details of my conversation with Chris, stay tuned for the next episode of The Tudor History & Travel Show, which will be released at the beginning of December. In the meantime, we must all hold our breadth and wait (not so) patiently to see what the dig reveals. You can be assured of one thing: The Tudor Travel Guide will be here to report all the latest news as it unfolds!

Other Sources:

Podcast Summary:

Podcast 1: On location at Collyweston, I chat to Chris Close, President of The Collyweston Historical and Preservation Society, about the archaeological dig aimed at uncovering more of the story of the once lost palace, once an important Tudor power-house belonging to Lady Margaret Beaufort. To listen to this episode, click here.

Podcast 2: In November 2023, ground-penetrating radar identified the position of the palace. Although there is much work to be done, I recorded a new podcast from the site. To listen to this episode, click here.

Notes:

If you want to learn more about Margaret Beaufort’s Collyweston, catch up with my interview with Dr Rachel Delman, lecturer at the University of York. Rachel’s area of expertise is grand aristocratic women of the medieval age and how they expressed power through the properties they owned.

Click the hyperlink to find out more about the Collyweston Historical and Preservation Society,

Reference was made above to a five year old William Cecil but left tantalisingly in the air. Who was William Cecil ? Pubs and I beleive a local hotel is named after him, so what is his story?

Hi Bernard. William Cecil became Lord Burghley under Elizabeth I; her first minister and principal secretary. One of the greatest men of the Elizabeth age in England. Thanks for asking!

A side track, historically; this caught my eye.Why?Because I am interested in period costume.Many men at Elizabeth 1st’s Court in late Tudor times wore their cloaks in a particular way known as ‘Colleywestonwards’-it has always intrigued me but I think I may have an answer.This style was to wear a cloak side ways, over one shoulder, as if they couldn’t be bothered-ie casually.Walter Raleigh for instance.It always puzzled me until I saw the map of the house and garden.I think it looks as though it was designed sideways on, with the gardens and ponds on one side of the house.Probably because it was the terrain and the prevailing weather in the area.And so the unusual name became a synonym for wearing fashionable wear sideways on-it’s a hunch and based on what I have seen on the map.I occasionally follow your blog and enjoy it.Thanks

How interesting! Well, there you go…I had no idea! Thanks for posting.

The “Collyweston cloak” is mentioned in M.J.Trow’s book ,”Crimson Rose”, and finally I have found the origin. What a well- informed person he is!

Fascinating entry. I can’t believe the amazing progress update on the dig!

I have lived and worked near Collyweston all my life. I am amazed that I had never heard about the Palace.

I found this article very interesting.

Thank you.

So glad you enjoyed it!

I love the Obsession and enough detail to inspire awe.

from Singapore

?