Margaret Beaufort and the Palace of Collyweston

Last year, I visited the site of the Palace of Collyweston in Northamptonshire, the Midlands powerhouse of that matriarch of the Tudor age, Margaret Beaufort. In today’s blog, I find out more about this incredible building when I interview Rachel Delman, a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Department of History at York University, who has studied Collyweston and the formidable Margaret Beaufort.

Note: This blog is an abbreviated transcript of an interview recorded for my monthly podcast, The Tudor Travel Show. To hear the interview, follow the link.

In Search of Margaret Beaufort’s Collyweston

Sarah:

Hello Rachel, It’s great to be talking with you! As you know, Collyweston is the reason I’m talking to you today. Of course, it was once one of the principal residences of Margaret Beaufort. Now, you have researched the house extensively and I wondered what specifically drew you to go in search of Margaret and her Midlands house?

Rachel:

I actually stumbled across her by accident! Back in 2011, when I was doing my MPhil dissertation, I wanted to write about people who commissioned, designed and used ornamental landscapes, essentially large scale gardens. I was in the library one day and looking through a volume of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments in England. I was looking at the Northamptonshire volume and I came across the page that covered the earthworks of Collyweston. They’re quite well preserved, even though there’s not much to see above ground today. I thought it looked like a really interesting site. With my interest in women’s history as well, I was fascinated to find out that the gardens were created by Margaret Beaufort and that the archival evidence was just amazing; there are so many volumes of building and household accounts.

Sarah:

So why did Margaret Beaufort establish a household at Collyweston?

Rachel:

That’s a really good question because today if you drive through it just seems like a charming, sleepy village. I think most people that pass through won’t know that it was the site of one of the most significant palaces of early Tudor England.

Margaret Beaufort acquired Collyweston in 1487, two years after her son was crowned King, after the Battle of Bosworth. It became her longest place of continued residence. Michael Jones, who has also written about the palace, has described it as a sort of satellite court in the Midlands. At this point, most of the Royal palaces would have been clustered in and around London.

We have to remember that the Tudor dynasty as we know it today was in its infancy at that point and this site would have allowed Henry and Margaret to keep an eye on things further north, where things were still a bit shaky and uncertain. Also, as a child, Henry had been educated mainly in Wales followed by exile in France so, for him, it was really important to assert his legitimacy through his mother’s connections.

Margaret’s mother, that’s Henry’s grandmother, Margaret Beauchamp, actually lived nearby at Maxey and Margaret’s half-siblings, the ‘St Johns’ and the ‘Welles’, were notable regional elites in the area. So, this really allowed Margaret Beaufort to cultivate these pre-existing connections. It worked to the advantage of both mother and son. There’s also lots of evidence that Margaret really loved this area. When she was married to Henry Stafford, she lived at Bourne in Lincolnshire and that was apparently an amazing property with rooftop gardens overlooking the fens.

Sarah:

Oh wow!

Rachel:

Yes, it must have been spectacular – another one I would have loved to have seen in its heyday. She apparently wanted, in fact she did want, to be buried there in the 1470s, but that obviously changed when she became the King’s mother and decided to go for the grander setting of Westminster Abbey. So yes, there is so much evidence that she really loved this area.

Sarah:

I see. That makes a lot of sense. When you set off to do your research, what was the primary question or questions that you wanted to answer when you started researching Collyweston as a location?

Rachel:

Well, I guess what the palace looked like, just because it has now disappeared and it does feel like a bit of a jigsaw puzzle trying to piece it all together. I was particularly interested in what it looked like during Margaret’s ownership because it was previously owned by Ralph, Lord Cromwell, who was Treasurer of England and before that by William Porter, who had originally built a house on the site. So I was curious to think about it as it was in Margaret’s day and how she used it to project her power and authority as the King’s mother and as the head of her own household.

Sarah:

I’d love you to describe to us what the house looked like, but before we delve into that, I wonder, was there anything in particular that you pulled out from the research that surprised, or fascinated, you?

Rachel:

Yes, that’s a really good question. Actually, I think it was just the sheer scale and magnificence of the palace. I don’t think I’d anticipated that when I first started my research. For example, there’s one entry in the building accounts that describes the three courtyards of Collyweston. That gives you an idea of just how massive it was because as, you know, we often get single or a double courtyard house in the Tudor period, but a triple courtyard house really is on palace-scale, isn’t it?

Sarah:

It is indeed, yes.

Rachel:

And that really surprised me. I think the other thing that I noticed is the fact that the building accounts were made over several years. This allows us to see the house evolving. We get a sense of it as a hub of frantic activity. It is a building site for much of the period. We often think about these houses as finished products, but it’s such a privilege to be able to see the process of it changing and to think about the ordinary people who were working on it from day to day as well.

We know that the Mastermason came from Grantham, which is just north of Collyweston, and all the workers came from within a four-mile radius of the site. So the stonemasons were coming from the local quarry villages and you get plumbers and joiners coming from Peterborough and Stamford, which are also nearby.

Sarah:

Yes, and you’ve just answered another question for me. I wondered whether Margaret Beaufort would have shipped people in from London, but no, she was very much supporting the local economy?

Rachel:

Yes, she was. You do get some references to things that have come from further afield. So, she does ship in some tapestries and those came via the port at Boston; they were Flemish tapestries so, presumably, had come over from the low countries. Also, one of the men, James [Matley] who worked on the gardens and the waterworks in the gardens, came from Bourton in Yorkshire, so slightly further afield, but there is a strong local workforce, which is really amazing to see.

Sarah:

Maybe you could now describe the house for us? I love thinking of myself as a time traveller and if I was to suddenly transport myself back to Collyweston five hundred years ago and started walking down the road towards the palace, and through the gate, what would I see?

Rachel:

I’ll try my best! So, as you approach the gatehouse, we imagine it probably looked something like Margaret’s foundation at Christ’s College in Cambridge. The gatehouse shows a full-body figural representation of Margaret and she’s clutching a book; she’s wearing her widows’ weeds or her vowess robes; she’s peering out over the streets of Cambridge and she’s surrounded by heraldic and dynastic iconography. So the Beaufort yales are there; there are Tudor roses; there are portcullises – it’s like a wonderful tapestry of colour proclaiming Margaret’s illustrious connections.

Sarah:

And so we’re walking through under this gatehouse and then what?

Rachel:

Next to the main gate, there’s also a prison and a council house which proclaims Margaret’s role as a regional dispenser of justice in the Midlands. What we have to remember is that, even though this was a kind of country retreat, it was also a political powerhouse with those buildings proclaimed the fact that Margaret is a royal representative in the area.

Sarah:

That’s so interesting. I have read about a lot of Tudor houses but I don’t think I recall hearing of a prison next to the gatehouse. That really does mark this out as a very particular site!

Rachel:

Yes, exactly. It is particularly unusual. We do have other features here, too, that are quite similar to other Royal palaces of the period and, again, show Margaret’s unique status. So, for example, she has a library as well here at Collyweston, which is fairly unusual. She also has a jewel house, too, which would be more commonly found in the royal palaces. We also know that next to the main gate there were workers’ lodgings, so some of the masons were actually lodged on site. During particularly busy periods, they would have lived in those temporary lodgings.

Sarah:

How long did it take to build the palace?

Rachel:

Well, it was built in various phases. So, as I say, Margaret Beaufort acquired Collyweston in 1487 and she did small amounts to it, but the main flurry of building activity happened just ahead of the royal progress in 1503. So there’s a sense that she’s getting everything ready for this big event.

Sarah:

Okay. So, taking us back on to our journey in time, we’re back in the courtyard. We’ve passed the gatehouse and the prison, etc. What faces us then?

Rachel:

It’s a bit of a muddle from the household and building accounts. I’ve managed to work out what’s in each of the courtyards, but where they were positioned is slightly trickier to work out. But we do know there was a chapel; that’s described in one of the later accounts as being equal to her son, the King’s.

There was also a great hall, as we might expect, in the main courtyard and an accompanying parlour, which would have been at its upper end. So the great hall was the ceremonial space of the household where there would have been feasting and dining, obviously. The parlour provided a more private, or exclusive, space for those sorts of activities and also for gaming and reading as well.

Sarah:

Speaking of gaming and reading, I know that you were really keen to find out more about how the palace was used. So what then did you find out about the rhythms of everyday life at Margaret’s Collyweston?

Rachel:

Piecing together the accounts of Parker and Fisher and the building and household accounts, we get quite a vivid picture of life in Margaret’s household.

We know that piety was obviously at the forefront of her mind. John Fisher tells us that she would rise early to pray in the mornings and also at the end of the day. She would pray in her chapel. We know that she also cultivated a reading circle at Collyweston. So, she was a patron of literature and a translator of texts. Several of the surviving books associated with her include the names of multiple members of her household. So we get a sense that she was disseminating ideas and circulating particularly pious texts

That gives you a glimpse into the social life of her household. She was also very active in the local community; that was something that really struck me when I was looking through the accounts, particularly in Stamford where she had close connections. She supported several religious houses in the area and she also put money towards the repair of bridges and church towers, in addition to being very active on her own estates and keeping a close eye on things closer to home. She was obviously very busy perambulating around the area.

Sarah:

You mentioned the courts and the prison. Did she preside over those or did she appoint people to do that on her behalf?

Rachel:

It’s a bit of both really. I don’t think we can say that she didn’t preside over them. I think we have a tendency to take agency away from women during this period a lot of the time, but the accounts suggest to me that she was very much a watchful eye and a stage manager over the events of her household.

In 1503, she presided over a dispute between town and gown in Cambridge and that was delegated to her for arbitration from the Royal Council. So, the Master of God’s House, which later became Christ’s College, was called to Collyweston to produce various documents. There were 14 counsellors present at that time, so we get a sense of her presiding over quite a substantial council in order to adjudicate and represent royal authority in the region.

Sarah:

Now, you’ve mentioned that there was the royal visit of 1503. This was the marriage procession of Margaret Tudor as she headed to Scotland to marry the Scottish king. That was obviously a big event in the lifetime of the house. Can you tell us more about it?

Rachel:

Yes, as you say, in 1503 Margaret Tudor and a courtly retinue arrived at Collyweston ready for these two weeks of celebrations ahead of her marriage to James IV of Scotland. Margaret Beaufort records this event in her book of hours that she’d inherited from her mother. I like to see this as a line of three Margaret’s – Margaret Beauchamp, Margaret Beaufort and Margaret Tudor: a maternal or matrilineal connection

Margaret Beaufort records the arrival of the party and we get a feel for how the household was being prepared for this event. The chapel has been newly painted with an image of the Virgin Mary and the Trinity, and in the gardens, new walkways are put in and there are ponds and summer houses there as well. So, we get a sense that the party definitely made use of the gardens during those two weeks. One of the details in her account says that she listened to her choir boys performing by the wood side on one occasion. Thus, we can imagine that there was musical entertainment outdoors, as well as lots of hunting and hawking, too. We know that Margaret loved hawking.

Sarah:

Perhaps you could remind us who was there because pretty much all the Royal family were there, weren’t they? With the exception, of course, of Elizabeth of York, who by this time had died.

Rachel:

That’s right. Margaret Tudor’s father and obviously Margaret Beaufort’s son, Henry VII, was there and also several senior members of the Church and all the notables of the royal court. Interestingly, for me (because I look at her house in Tiverton in Devon), Catherine Courtney, Edward IV’s daughter, was there as well.

So, we do get this sense of a large company being there in preparation for the event. Margaret actually builds a new lodging which takes 10 months to build and cost £450 – so eye-wateringly expensive! That’s devised to house Margaret Tudor and the main members of the royal wedding party, while some of the others stay at Maxey nearby. No-one seems to have pointed that out before, but it is something I noticed in the accounts. Margaret still uses her mother’s residence at Maxey in order to emphasise her links to the area.

Sarah:

So that’s used as an overspill property, basically?

Rachel:

Basically, yes.

Sarah:

Wow! So, there was also a brand new wing built specifically to house the royal party for this event?

Rachel:

Yeah. So it was basically one side of one of the ranges, presumably the inner courtyards. From what the documents say about its positioning, I think it would have overlooked the deer park and the gardens, so it would have offered spectacular views over the Wellands.

Sarah:

I always think it must have been a very bittersweet two weeks because, of course, it was from Collyweston that Margaret set off on the rest of her journey and said goodbye to her family.

Rachel:

It does seem that Margaret was very close to her granddaughter and that she prevented her from going to Scotland too early. That was probably rooted in the fear she had around her own early pregnancy and the traumatic experience of giving birth. She was very protective of Margaret.

Also, Margaret Beaufort was very much the stage manager of this spectacle. As the party get ready to leave, she allows only those who are related to Margaret Tudor by blood into the great hall to bid her farewell. So, there is this big emphasis on family connections. She’s given a book of hours by her father at this point. They must have been delighted that this infant dynasty was doing so well but, at the same time, we can’t leave out the human element in history. It must have been hard for everyone to say goodbye after those few weeks.

Sarah:

What of the house after that?

Rachel:

That’s another good question. After that, Margaret’s house, I think, becomes a bit more of a spiritual retreat. There’s more of a focus on her piety. She creates a new set of apartments for herself and there’s a strong emphasis on views over the chapel from those apartments. That said, we shouldn’t necessarily think about her hiding away; she’s still one of the most important people at this time and she was still very active in the local community.

The Death of Margaret Beaufort and the Decline of Collyweston

Sarah:

Of course, all good things come to an end. Margaret Beaufort died in 1509. When was she last at Collyweston? Can you tell us a little about her demise and also, perhaps more importantly, about the demise of the house?

Rachel:

The accounts take us up to 1507 – so two years before her death. We get the sense that she was more London-centric by then. The house, sadly, has a bit of a chequered history after Margaret died in 1509. It goes to Henry VIII’s bastard son, Henry Fitzroy. I’m not sure what Margaret would have thought of that, given her strong emphasis on lineage and dynasty. Maybe she was turning in her grave!

Sarah:

I can imagine!

Rachel:

Exactly. Elizabeth I came to own the house later. There isn’t a sense that she’s there very much, but she does build a banqueting house in the garden. So again, we’re seeing how spectacular the setting was and how wonderful these gardens were.

By the seventeenth-century, it’s passed into the hands of the Heath family. Edward Heath is responsible for dismantling it. We know that from the accounts. Then, the Tryon family build a later house on the site. It seems that they do a pretty good job of redistributing all the materials because the only things we have today are a sundial from the later house and a wall from the seventeenth or eighteenth-century. As you walk through the village, you do occasionally see quite impressive stones in some of the walls and buildings and I do wonder whether some of these materials came from the palace.

Sarah:

And may be it is worth saying here that, of course, most of the area originally occupied by the palace is now under people’s back gardens so you can’t actually go and see anything. But there is the local parish church, which has a wonderful doorway from the original building, even before Margaret’s time, is that right?

Rachel:

Right, yes, it does. It is associated with William Porter’s house, originally built on the site in the early fifteenth-century, around 1415. This house predates Margaret’s palace. There is also a chapel on the south of the church, which was Margaret’s chapel and is now used as a site for local displays.

Sarah:

It’s amazing what you can find hidden away in English parish churches! It’s always worth a look. There’s a top tip for anybody visiting England – if you go to visit any village or town, make sure you go to the church because you may well be amazed by what you find!

Rachel:

Definitely. I totally agree with that.

Sarah:

Thank you. I think that draws our discussion to a close. Thank you so much, Rachel, for sharing all of your research into what was clearly an epic Tudor house.

Rachel:

Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

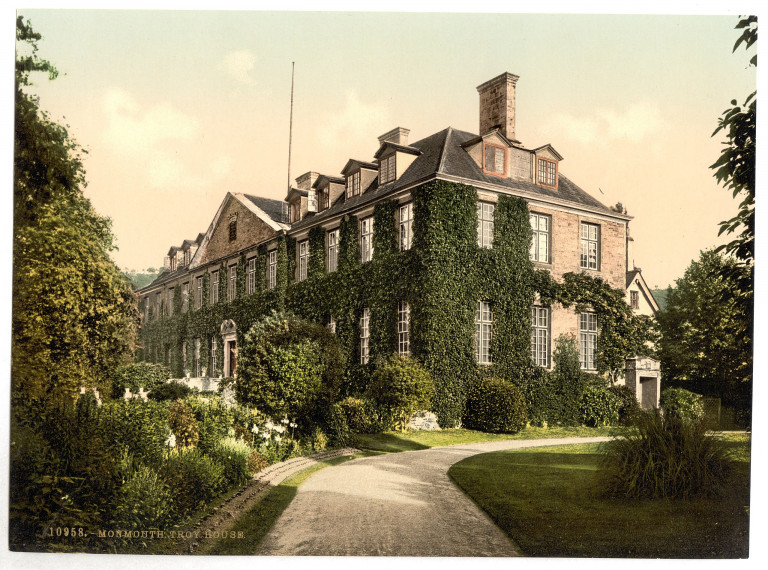

Rachel Delman: Biography

Rachel Delman is a Historian of the late medieval and early Tudor period. She is based at the University of York. Her research focuses on women and their roles in shaping and using both domestic and non-domestic architecture to express their power, agency and influence. At the moment, she is working on her first book which, hopefully, is due to be published by Oxford University Press in the next year or so. It’s based on her doctoral research, completed at Oxford in 2017. It looks at the physical and social space of five houses that were commissioned or headed by women during the period 1450 to 1550. Those are Margaret of Anjou’s Palace at Greenwich; Alice Chaucer’s House at Ewelme in Oxfordshire; Catherine Courtney and her castle at Tiverton in Devon; Margaret Pole’s house at Warblington in Hampshire and, of course, Margaret Beaufort’s Palace at Collyweston. Connect with Rachel via twitter on @rachel_delman.

Rachel Delman is a Historian of the late medieval and early Tudor period. She is based at the University of York. Her research focuses on women and their roles in shaping and using both domestic and non-domestic architecture to express their power, agency and influence. At the moment, she is working on her first book which, hopefully, is due to be published by Oxford University Press in the next year or so. It’s based on her doctoral research, completed at Oxford in 2017. It looks at the physical and social space of five houses that were commissioned or headed by women during the period 1450 to 1550. Those are Margaret of Anjou’s Palace at Greenwich; Alice Chaucer’s House at Ewelme in Oxfordshire; Catherine Courtney and her castle at Tiverton in Devon; Margaret Pole’s house at Warblington in Hampshire and, of course, Margaret Beaufort’s Palace at Collyweston. Connect with Rachel via twitter on @rachel_delman.

Margaret Beaufort has become an interest in the past year, and this was a fantastic episode that supplied detail into the overall woman. Another one for the time machine list of people to meet, though she might have been a bit terrifying!

Thank you, a fascinating post. I am a direct descendant of all these women.