Bolton Castle and the Vengeful Prisoner of Wensleydale

Cover image: Bolton Castle in Wensleydale, by kind permission of Anita Watson.

In the last post, we followed in the footsteps of Mary, Queen of Scots, witnessing her daring flight from Borthwick Castle, Scotland, to England in 1567. Today, we time-travel to visit Mary at Bolton Castle, now the captive kinswoman of her ‘cousin’ Elizabeth. Almost two months to the day have passed since she arrived off the coast of Cumberland and came ashore, seeking sanctuary from Elizabeth I.

Initially received as a guest, the tide was turning fast, and Mary’s freedom was gradually being stripped away, even in those early days. After landing in England on 16 May 1568, the Scottish queen was held briefly at Carlisle Castle before being spirited away further south to the relative ‘safety’ of North Yorkshire. Her destination was Bolton Castle, the ancestral home of Lord Scrope of Bolton. Mary was reluctant to travel further from her kingdom of Scotland, only doing so peaceably on assurances that she could continue her correspondence across the border. We shall join her at Bolton Castle.

Bolton Castle: The Palace-Fortress of North Yorkshire

Bolton Castle is a wonderful place to mark on your itinerary, not only because of the singularly rugged beauty of surrounding Wensleydale but because, as a building, Bolton Castle has been noted as one of the ‘most complete and best-preserved palace-fortresses of medieval England’ [Emery]; to boot, the original chambers in which Mary passed her six months at the castle are still preserved. Who could ask for more?

Situated in the wide-open countryside of lush grassland, adjacent to what Leland, the sixteenth-century cartographer and antiquarian, describes as a ‘craggy hillside’, Bolton Castle is an impressive sight. Arriving there on 15 July 1568, ‘just one hour after sun setting’ (which, given this was mid-summer, must have been sometime around 9 pm-10 pm), one of Mary’s jailers, Sir Francis Knollys, tells us of the impression Bolton Castle made upon him at first sight:

The house appearth to be very strong, very fair and very stately, after the old manner of building [ie. it is a medieval castle] and it is the highest walled house that I have seen.’

And although the castle is now partially ruined (part of the north and west ranges were demolished after they collapsed in the eighteenth century), as a visitor, even today, you will appreciate Sir Francis’ description, for it is an imposing sight; its angular lines, soaring walls and lack of elaborate, external ornamentation create an aura of foreboding. However, despite the building’s sombre personality, Bolton Castle had been constructed as a luxurious family home that sported a highly innovative and complex design during the latter part of the fourteenth century.

Bolton Castle: A Medieval Trend-Setter

The castle was quadrangular in design, with its four tall ranges orientated around a central courtyard, linking four massive five-storey towers in each corner. Leyland claims that it took around eighteen years to build at the astronomical annual cost of £700. Unlike the motte and bailey design of earlier castles (where there were often several different buildings arranged within an inner and outer courtyard – see the post on Framlingham Castle to understand this better), this one structure contained all the chambers, offices, stores and other lodgings required for the running of a high-status family abode of the day.

According to the architectural historian Anthony Emery, the internal layout was (and still is) equally remarkable. Not only does the building contain the usual great hall, chapel, kitchens and domestic offices, but there are also suites of chambers, halls and lodgings which have been carefully graded to underscore status, all linked together ingeniously within thick stone walls, to connect the different levels inside one integrated building. This building would feel like a veritable rabbit warren, albeit one that had been carefully and perfectly designed to house Lord Scrope, his family, guests, officers and servants – even his horses, which were kept in stables on the ground floor!

There was only one entrance to the castle, which remains the entrance today. Whilst it is not particularly impressive, its simplicity was a bonus to Mary’s jailers. In a letter to William Cecil, shortly after Mary’s arrival at Bolton Castle, Sir Francis commented that ‘half the number of these soldiers may better watch and ward the same [Mary], than the whole number thereof could do at Carlisle Castle’, i.e. it was much more secure, and therefore easier to guard the Scottish Queen.

Also notably, somewhere in the castle, perhaps in the courtyard as at Hampton Court Palace, there was once an astronomical clock, which Leland noted ‘marked the movements of the sun and the moon, and other predictions’.

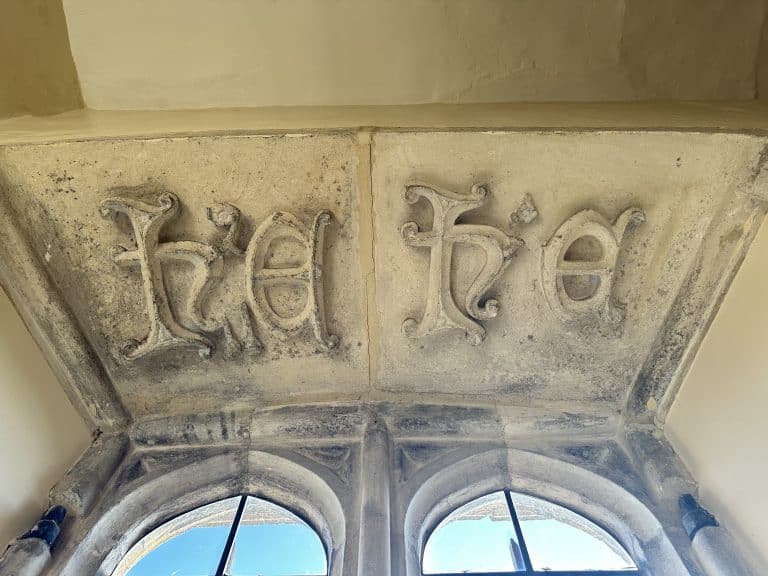

Entrance to the great hall was from the ground floor via a door in the north-east corner of the courtyard, up a flight of steps and into a small lobby that led into the low end of the hall. The hall was not particularly large. However, there was at least one remarkable feature. In the 1530s, John Leland visited Bolton Castle and was clearly given a guided tour of the house. He noted that the ‘chimneys were built into cavities in the walls between the windows, so that ‘smoke is very cleverly drawn off from the hall fireplace’ (probably a central hearth) – a kind of medieval wall vent!

The high end of the hall connected through into the north-west tower and west range, which in turn linked through to the south-west tower. This range contained the principal living quarters of Lord Scrope. As befitting Mary’s status, these were surrendered for her use during the duration of her stay at Bolton Castle. Luckily for us, it is this range and these chambers which remain mostly intact to this day.

Mary, Queen of Scots’ Privy Chambers

Today, access to the rooms in the south-west tower is by a stone spiral staircase with the principal living chamber, or solar as it is often known, on the first floor, Lady Scrope’s bedchamber on the second, and Lord Scrope’s (temporarily Mary’s) bedroom on the third floor. Whilst the rooms are identical in footprint, the last of these bedchambers has the most breathtaking views of the Wensleydale countryside. It was here that we could find Mary, gazing out from her isolated prison, hopeful that her ‘cousin’ Elizabeth would help her take back her kingdom, but also perhaps aware that the machine of the Tudor state had begun to work against her.

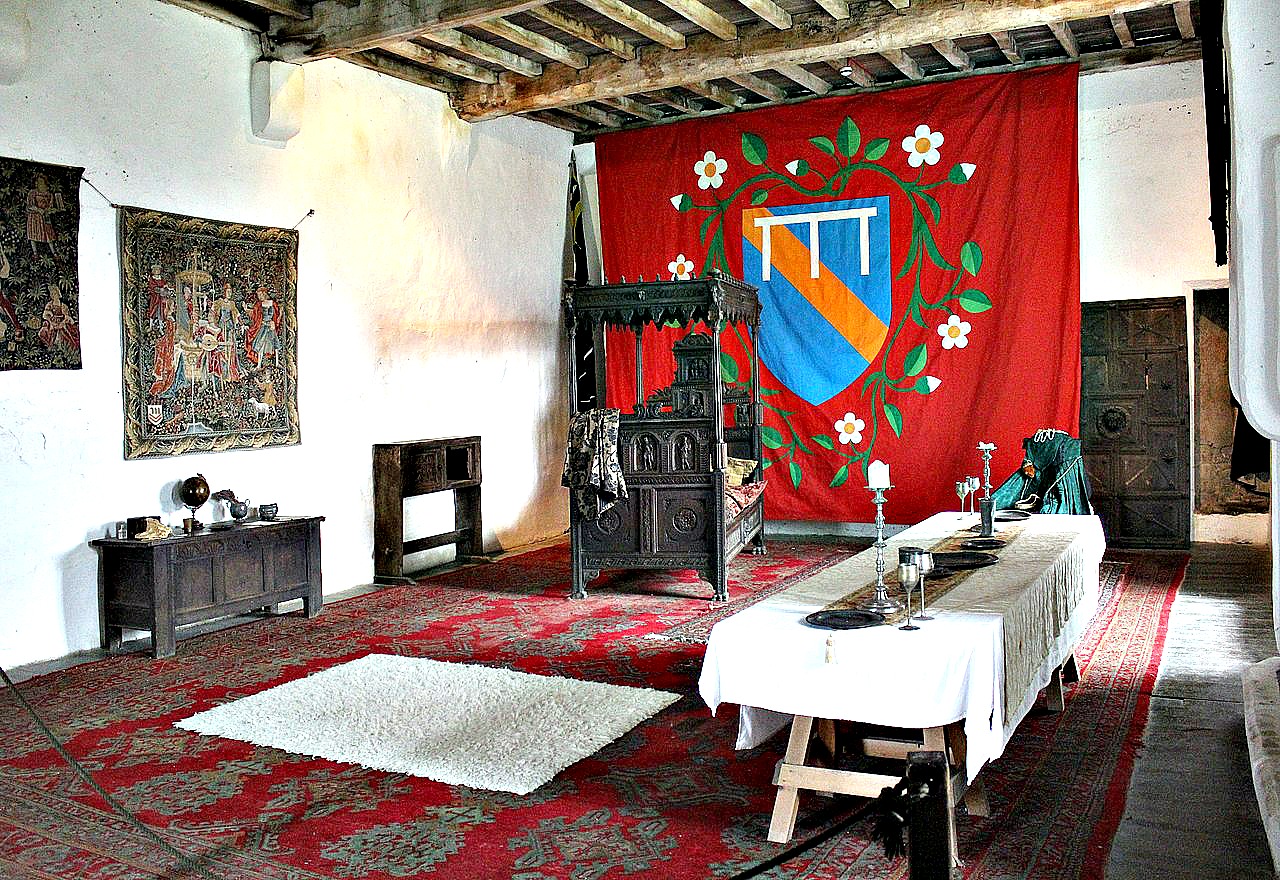

On the first floor, visit the solar and an adjoining hall – one of four originally built into the castle walls. This was slightly smaller than Bolton Castle’s great hall and was part of the privy residence of Lord and Lady Scrope. Today, it is known as the ‘Great Chamber’.

In these living chambers, we can pause momentarily and consider how the interiors might have been furnished in the mid-sixteenth century. Although a prisoner, Mary was still a queen, and her status was provided for accordingly. According to Mary’s biographer, John Guy, Mary travelled with around 30 carts full of her belongings. We can imagine that the bare stone walls of Bolton Castle would have been decorated with fine tapestries and carpets. We also know that whilst at Tutbury Castle, the Scottish queen kept a cloth of estate embroidered with the words, En ma fin est mon commencement (‘In my end is my beginning’: her mother’s motto).

There is no reason to believe she did not keep the same cloth of estate at Bolton Castle, perhaps in the Great Chamber, which would have acted, I presume, as a kind of presence chamber. In these rooms, Mary was attended by six gentlewomen, although Knollys suggests that none of them was ‘of reputation’ [of significance]. One of these was one of ‘The Four Marys’ who famously attended the Scottish queen: her name was Mary Seaton.

Through Mary Seaton’s talents, we know a little more about the queen’s love of fashion and the visual art of queenship. In another of Knollys’ letters, we hear how Mary exclaimed to her jailers that her companion ‘was the finest busker, that is to say, the finest dresser of a woman’s head of hair that is to be seen in any country’ and that they had indeed seen proof of this, with many ‘pretty devices’ set in her hair such that every day, ‘she wore a new device of head dressing without cost’, which ‘set forth [the queen] gaily well’.

The queen was also an accomplished needlewoman and would have spent a good deal of time attending to her needlework during her period at Bolton Castle. Some of her embroideries survive, such as ‘The Catte’ above, which was worked during her imprisonment. (The cat, by the way, is thought to have symbolised Elizabeth, with Mary the unfortunate mouse!). Also, whilst at Bolton Castle, Sir Francis spent time teaching Mary how to read and write in English, her native tongues being both French and Scots. He leaves us a wonderfully evocative account of Mary’s character in a letter he penned to William Cecil after his first meeting with the Scottish queen in Carlisle in June 1568:

‘This lady and princess is a notable woman. She seemeth to regard no ceremonious honour, beside that acknowledging her estate regal. She showeth a disposition to speak much, to be bold, to be pleasant and to be very familiar … She showeth a great desire to be avenged of her enemies: a readiness to expose herself to all perils for the sake of victory … the thing that she most thirsteth after is victory.’

It seems that revenge against those who had wronged her and stolen her throne was foremost in her mind. Typically, Mary’s time at Bolton Castle was not without drama. Elizabeth had the queen tried over the controversial claims that she had been involved in her second husband’s murder (Lord Darnley). The trial was conducted at York; Mary was not present, nor did she see any evidence that was laid against her. However, the court found neither for nor against her. As many commentators have said, it was nothing more than a ‘show trial’.

There is also local folklore, which tells the tale of Mary’s escape from Bolton Castle. Mary was allowed to hunt at this point in her imprisonment, albeit under close supervision. Knowing the land, it is said that one day, she managed to slip past her guards and escape into thick woodland near the castle. As she was pursued by men, dogs and horses across the Yorkshire countryside, the queen is said to have snared her shawl on a briar.

Allegedly, Mary was caught before she reached the nearby town of Leyburn. Thereafter, a ridge of hills outside the town has been known as ‘The Shawl’. This land has public access, so you can follow the trail of this local legend. Whether it is true or not? Well, I’ll leave that to you to decide…

Visitor Information

For further information on the seasonal opening times of Bolton Castle, check out the website here.

If you are visiting Bolton Castle, and castles are your thing (of course they are! Who am I kidding?), nearby are the mighty ruins of two very notable castles: those at Richmond and Middleham (childhood home of Richard III), which you should factor into your visit, particularly if you are staying in the area for 2/3 days. They are within easy reach of each other, so long as you have a car.

Also within reach are two stunning abbeys, both of which were ruined during The Dissolution of the Monasteries: Fountains Abbey (53 mins by car) and Jervaulx Abbey (23 mins by car). The former is one of the country’s most popular National Trust destinations and illustrates the sheer scale of these medieval institutions. The second, you may well have all to yourself. You must park and walk across a field to get to the impossibly romantic ruins. On a hot sunny day, a picnic there would be perfect amongst the flower-covered, crumbling walls.

If you are visiting Jervaulx, then you are close to Snape Castle, which was, of course, the Yorkshire home of Katherine Parr when she was Lady Latimer during the period encompassing The Pilgrimage of Grace. You cannot access what remains of the castle, but you can see some of its ruined parts and visit the chapel, which Katherine would have once used for worship.

If walking is your thing, and you love the idea of following in the footsteps of folklore, then you can walk from Leyburn to Bolton Castle, which is around 6.5 miles one way. This walking site gives you some ideas of possible one-way or loop walks that take in ‘The Shawl’.

Can I ask why you put ‘cousin’? Do you doubt Elizabeth’s paternity? If Henry VIII was her father she is in fact Mary’s Cousin as she was the granddaughter of Henry’s sister

Hi Hannah, No, I am not questioning paternity. So, for me, strictly speaking, for someone to be a cousin, their parents must be siblings. As you point out, Mary was the grand-daughter of Henry VIII’s sister, Margaret. So not strictly, in my book, a ‘cousin’ but maybe a cousin ‘X’ times removed – twice removed? I am not an expert on labelling the nuances of family trees. Hence I wrote it as I did. I hope makes my thinking clear. Thanks for the question!