Middleham Castle: Daunting Fortress, Luxurious Home and One Priceless Jewel!

Middleham Castle sits in the wide-open, rugged and beautiful landscape of North Yorkshire, about 230 miles north of London and 45 miles northwest of York. It was recounted by Tudor antiquary, John Leyland, as ‘a pretty market town, and standith on a rocky hill, on the top whereof is the castle meately welle dyked with the castle joynith hard to the toun side on the south’. He also described the terrain approaching Middleham as ‘difficult and rocky moorland with few trees in sight’. Even today, 500 years later, as you drive through the Dales, you feel that sense of open, expansiveness and endless fields, marked out by the crisscrossing of dry stone walls.

Another early account of Middleham Castle comes from Francis Grose, author of ‘The Antiquities of England and Wales’ in the late eighteenth century. He noted that Middleham stood just 7 miles from another, historic, northern castle: Bolton (where Mary Queen of Scots was imprisoned in the 1560s). He believed Middleham had the superior advantage of more distinctly commanding the wood; the finely scattered villages, and the lazy progress of the River Ure through spacious meads (or meadows), on the eastern part of Wensleydale.

A Brief History of Middleham Castle

Although Middleham Castle was not to be used by the Tudors, it was one of the principal homes of Richard III. In the run-up to the decisive Battle of Bosworth, in which Henry Tudor would finally seize the crown from the Yorkist King, Richard would reside at the castle. His only son and heir, the so-called ‘Edward of Middleham’ would live and die there. Middleham is a castle that grew out of the Norman conquest of England, its wooden structure being replaced by the current stone castle in the twelfth century.

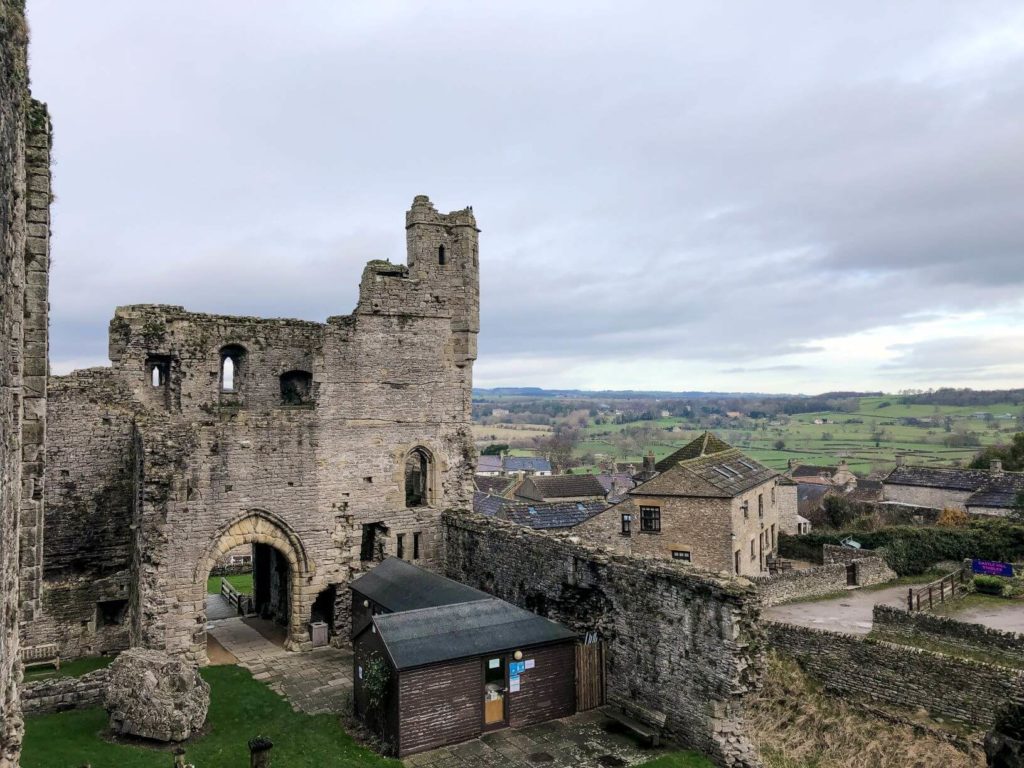

However, it would not be until the fourteenth century, under the powerful Neville family, that the castle would reach its pinnacle. After the massive central keep was constructed in around 1170, the subsequent 300 years saw intermittent modernisation and improvements to the castle. These included the raising of the castle’s curtain walls and the construction of a series of lodgings built inside and around three sides of the courtyard. It is suggested these improvements were inspired by a building project going on at nearby Bolton Castle. After realising the new innovations in castle architecture there, the Nevilles arguably set out to emulate this and improve the facilities at Middleham.

As today’s castle ruins are extensive, we can form accurate reconstructions of how the Neville’s formidable Wensleydale home looked. Essentially, a massive central square keep dominated the castle site. A central dividing wall created two parallel chambers, much the same as you can see surviving at Dover Castle today. On the ground floor were the kitchens and service offices. The great hall was on the first floor, accessed by an external staircase that clung to the eastern wall of the keep.

Within the keep on either side of the central divide were two chambers, the Great Chamber to the south leading to a more private, inner chamber to the north. A chapel was sited adjacent to the great hall, again at first-floor level (so it could be accessed from the Lord’s principal first-floor chambers). Externally, this chapel could be seen protruding from the keep’s east wall, next to the main entrance to the castle’s inner courtyard. Throughout the castle’s history, the keep served as the main focus for entertainment, around which life at the castle revolved.

The single and paired lodgings ran around the north, south and west walls of the castle’s curtain wall and provided accommodation of varying status to serve the Lord’s household, friends and guests. All with garderobe facilities and fireplaces, they provided the height of medieval luxury and comfort.

Those lodgings on the first floor were taller than the ones beneath, again highlighting their superior status – and thus were used by the most senior persons occupying the castle. One of these first-floor lodgings on the south side was particularly grand, with its own hall. The suite could only be accessed via an elevated, covered bridge leading from the keep. The close communication between the keep and these first-floor guest lodgings suggests that only the most honoured guests would make use of such accommodation – similar to being given the penthouse suite at a modern hotel! Architectural historian, Anthony Emery, makes the statement in his ‘Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales’ books that the layout and grandeur of the castle’s lodgings made a ‘rich architectural statement’ about the graded high-quality accommodation required for a leading, landed magnate of early fifteenth-century England.

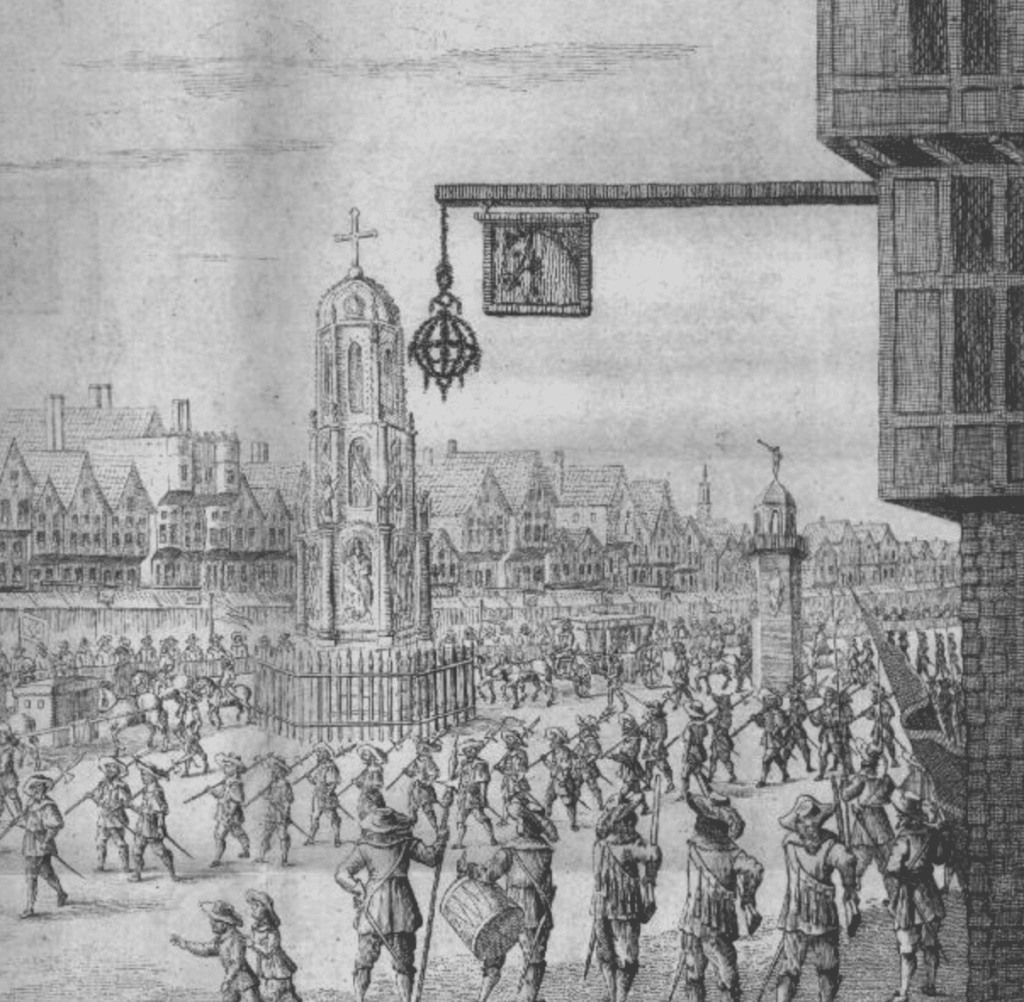

In April 1537, after the Pilgrimage of Grace, orders were given to repair Middleham Castle ‘to receive the king’ – Henry VIII. However, he never stayed at the castle or went anywhere near it during his 1541 Progress. Nevertheless, the castle was surveyed in 1538, perhaps in preparation for such a visit. Many distinct rooms are listed in the inventory, but perhaps most interesting is the mention of a nursery in the south-west corner tower of the keep. Although there is no distinct proof, it is reputed to be where Edward of Middleham was raised.

Family ties led to Richard III’s association with the castle. His cousin, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, (popularly known as ‘The King Maker’) was instrumental in helping Edward, Richard III’s brother and Earl of March, ascend the throne in 1461. After defeating the Lancastrian armies, Edward IV deposed King Henry VI.

When his elder brother became king, the future Richard III was around 9 years old. He was sent to live in the Earl of Warwick’s household at Middleham in 1465 in order to receive an education befitting an aristocratic gentleman. As Warwick was considered one of the most accomplished military leaders of his day, this would be a fine education indeed. However, Richard Neville fell out with his cousin in 1467, and Edward IV was briefly imprisoned at Middleham before escaping while out hunting in one of its parks. Richard Neville was later defeated and killed by Edward’s army at the Battle of Barnet in 1471. Richard III became Richard of Gloucester and was given the estates of Middleham and another enormous property, Sheriff Hutton Castle, just outside York.

A year later, Richard III married Neville’s younger daughter, Anne, and Middleham remained an important base for the new duke. Anne gave birth to their only child at Middleham Castle, who, as we have heard, was thereafter known as ‘Edward of Middleham’. He was raised at the castle and lived to see his parents crowned King and Queen of England before his death at Middleham in April 1484.

The Croyland Chronicle, an important source of English Medieval history, details the event: ‘In the month of April, on a day not very far distant from the anniversary of king Edward, this only son of his, in whom all the hopes of the royal succession…was seized with an illness of but short duration, and died at Middleham Castle…On hearing the news of this, at Nottingham, where they were then residing, you might have seen his father and mother in a state almost bordering on madness, by reason of their sudden grief.’

In the meantime, when Richard III was slain at Bosworth in August 1485, all his estates, including Middleham were forfeited to the Crown. Richard’s death knell was shared by one of his favourite residences and, thereafter, the castle fell into disuse. Middleham’s substantial ruins represent a crucial epicentre of the York’s last stand in England in the War of the Roses and are well-worth including on your travel itinerary.

The Middleham Jewel

It is impossible to talk about Middleham Castle without touching upon one of the treasures of Medieval England, which was plucked out of the earth close to the castle. This is the so-called ‘Middleham Jewel’, which was found not far from a footpath that connected Jervaulx Abbey to Coverham Abbey and which ran through Middleham.

Found in 1985, and initially sold at auction for £1.3 million, it was subsequently saved for the nation as it was deemed by the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art to be of outstanding cultural importance. Thankfully, it was purchased by the Yorkshire Museum, in York, where you can see it on display to this day.

This 600-year-old object is so exquisite, it is beguiling. I defy you not to stand and gawp in wonder as you ponder on the lady who once wore this around her neck, probably as a pendant upon a necklace. Such pieces of jewellery were fashionable in the second half of the fifteenth century when ladies wore gowns with low-cut necklines.

The jewel is lozenge-shaped and measures 46mm high and 48mm wide. It is made of gold, which has been ornately engraved with the Trinity on one side and scenes of the Nativity on the rear. A large sapphire is displayed on the front side and at one point, pearls were attached around the edge, although these have since been lost. A Latin inscription, which was once enamelled (you can still see a tiny fragment of enamelling surviving on the first letter – ‘E’) reads, Ecce agnus dei qui tollis peccata mundi miserere nobis tetragrammaton ananizapta. (Behold the Lamb of God who takest away the sins of the world). This runs around the border on the front side of the jewel, while images of 15 saints occupy the same border on the reverse of the pendant.

It is believed that the Middleham jewel was made in England, probably commissioned from a goldsmith in Cheapside (if you want to find out more about the goldsmiths of Cheapside, listen to this podcast with Natasha Awais-Dean, a Tudor jewellery expert). It’s attribution to the work of an English goldsmith is at least in part because of the appearance of St George, the Patron Saint of England, as one of the 15 saints on the rear of the jewel.

While the religious iconography of the Middleham Jewel is clear, we should also remember that at the time this pendant was commissioned by its wealthy owner, precious metals and gemstones were selected specifically on account of properties thought to confer upon the wearer certain types of protection or good fortune. Gold was believed to be advantageous to health, while the sapphire ‘protects the body, can release captives from prison and inclines God to hear favourably the prayers of the wearer. It promotes peace and reconciliation, can arrest internal heat and excessive sweating and is good for ulcers, eyes and headaches’.

The last two words of the inscription Tetragrammaton and Ananizapata. The former denotes the four Hebrew letters used to indicate the name of God. Ananizapata is a word that has magical connotations; during the medieval period it was believed to protect against drunkenness and epilepsy; this was known at the time as the ‘falling sickness’. Taken altogether, the inscription alongside the gemstone suggests that its owner was concerned with matters relating to their health and looked to it for protection against illness.

The final aspect of the Middleham Jewel that we need to consider is its contents. The panel on the back can be slid open to reveal a hidden compartment. When the jewel was discovered, the pendant was found to contain three-and-a-half small roundels of silk, embroidered with gold thread. According to John Cherry’s book The Middleham Jewel and Ring these were ‘clearly of great importance to the owner of the jewel and were revered as relics’.

There is little doubt that along with its magical properties to protect against illness, whoever owned the pendant was devoutly religious. It is believed that the pendant may have originally been an Agnus Dei; a container that housed a round, wax seal stamped with the image of the Lamb of God. These seals were given out by the Pope on Easter Sunday – some being sent abroad to be given as gifts to important persons. They were greatly valued by women in relation to pregnancy as it was believed that such Agnus Deis would patient the life of the mother and child.

And on that latter point, frustratingly, we cannot pinpoint with certainty who owned the jewel. Clearly, this was an exceptionally wealthy and pious lady, who lived in the second half of the fifteenth century. Perhaps this woman was concerned about the health and the safe delivery of children. Given that Middleham was the main base of the Neville family, including Anne Neville, after her marriage to the future Richard III, perhaps it even belonged to her? Frustratingly, we will never know, but it is delicious to ponder the possibility as we gaze upon the locket today, fittingly preserved on Yorkshire soil, where it had lain quietly undiscovered for over 500 years.

Sources

‘Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales – The North’ by Anthony Emery.

‘Itinerary’ by John Leyland.

‘A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1‘, originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1914.

‘Ingulph’s Chronicle of the Abbey of Croyland: with the continuations by Peter of Blois and anonymous writers‘, Bohn’s Antiquarian Library. Translated by Riley, Henry T. London: Henry G. Bohn, 1854.

‘The Antiquities of England and Wales‘ by Francis Grose, London: S Hooper, 1785-87.