William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Name and Title: William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1st Baron Burghley)

Born: 13 September 1520

Died: 4 August 1598

Buried: St Martin’s Church, Stamford, Lincolnshire.

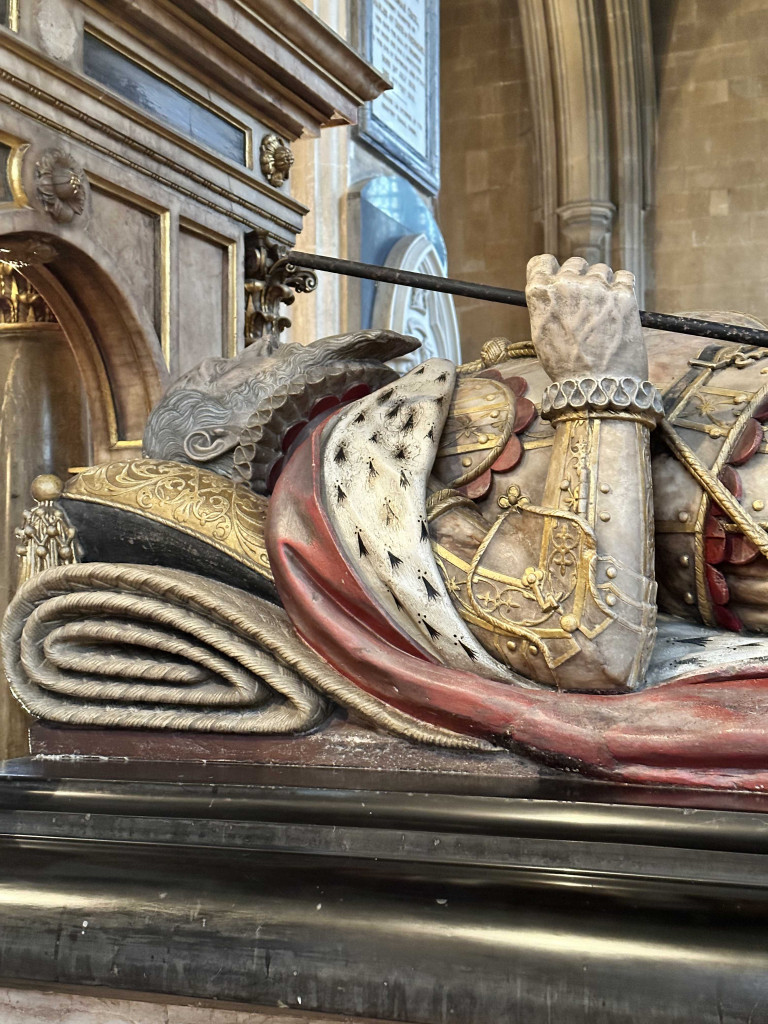

Image: Author’s Own.

The Early Years of William Cecil

William was born in Bourne, Lincolnshire, on 13 September 1520 to parents Sir Richard Cecil and Jane Heckington. The paternal side of his family was from Wales; William’s grandfather had previously moved to Stamford from the Welsh Marches and Anglicised their name from Seisyllt to ‘Cecil’.

The greatest statesman of the Elizabeth age would have close ties to the town all his life, eventually building his magnificent country home, Burghley House, just south of Stamford. He would also choose to be buried there following his death in 1598.

At the time of little William’s birth, Henry VIII was still married to Katherine of Aragon. Indeed, that summer, the royal couple led the entire Tudor court across the English Channel to participate in THE most celebrated Tudor party of them all: The Field of Cloth of Gold.

In 1520, Sir Richard was a royal page, and he attended the lavish affair, which took place in June of that year. Given his presence at the event, it is easy to imagine that the gossip he brought back, either in person or via letters, must have been the talk of the town. Then, as summer gave way into Autumn, little William, Richard and Jane’s only son, entered the world.

The seismic religious changes that Cecil himself would champion in the second half of the sixteenth century had yet to sweep England. So, we can assume William was raised in a Catholic household. As has already been alluded to, his family were well-to-do citizens of the area. William’s paternal grandfather, David Cecil, had been yeoman of the chamber to Henry VII. He was elected Member of Parliament for Stamford five times between 1504 and 1523. Later, he became Sergeant-of-Arms to Henry VIII (1526), Sheriff of Northamptonshire (1532), and a Justice of the Peace for Rutland.

Interestingly, David also owned The George Inn in the centre of Stamford, which still stands today. This inn was a place of some significance, for the town was a major stopping-off point for travellers moving between London and Edinburgh, being located close to the Great North Road. At the time, this highway was the foremost road connecting the North with Southern England. As William grew up, he must have witnessed a steady stream of important and influential visitors coming and going through the town – and perhaps even through his grandfather’s inn.

As a boy, William was schooled first at the King’s School in Grantham and afterwards at Stamford. Later in life, when Cecil had accumulated wealth, power and status, he endowed this latter school, no doubt in gratitude for the service rendered to him during his early years.

Learning Statecraft – From University to the Council Chamber

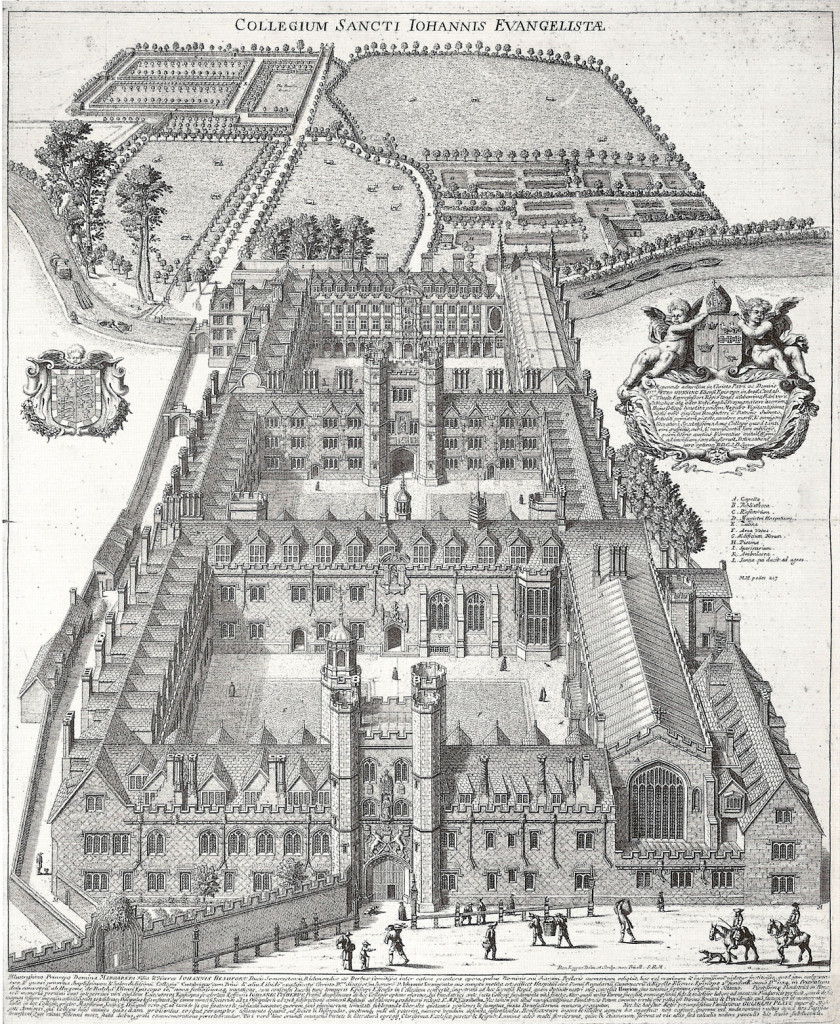

In the Spring of 1535, when William was 14, he left home, travelling 50 miles south of Grantham to take up his place at St John’s College, Cambridge. The college had been created at the beginning of the sixteenth century with money bequeathed by Margaret Beaufort. She intended to find a second college in Cambridge but died before building work began.

Cambridge became well-known as a hotbed of radical religious thinking. So, it is little surprise that Cecil emerged as a zealous proponent of Evangelical doctrine, later known as ‘Protestantism’.

While at Cambridge, William met his first wife, Mary Cheke. She was the sister of John Cheke, a Cambridge scholar and, at one point, tutor to the future Edward VI. Impulsively, he married Mary, it seems for love, when he was 21. Besides Mary’s death in 1543, little seems to be known about her, but together, they had one son, Thomas, who would grow up to be the 1st Earl of Exeter.

William’s second marriage came four years later. His new bride was an exceptionally learned woman who was Cecil’s junior by six years. They had six children together; however, only three would survive to reach adulthood. Perhaps the most famous being their sole surviving son, Robert Cecil, who replaced his father as Elizabeth’s Secretary of State after William died in 1598.

Mildred and William remained married for over 40 years, being parted only by Mildred’s death in 1589. Like her husband, she died at Cecil House on the Strand in London. However, unlike her husband, she was buried in Westminster Abbey alongside her daughter Anne, Countess of Oxford.

Elizabeth Tudor’s Guardian Angel…

Having completed his education at Gray’s Inn in London, Cecil soon entered the sphere of the rich and powerful of Tudor England. He served first in Edward Somerset’s household. At the time, Somerset was the most powerful man in the land, serving as Lord Protector of England during the minority of this nephew, Edward VI. However, when the Duke was arrested in 1549, Cecil was caught up in the wake of the coup and committed to the Tower.

While his erstwhile master was executed, William was released within three months thanks to a relationship forged with the emerging dominant force at court: John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. Soon after, William was created one of Edward VI’s two Secretaries of State.

However, in July 1553, Edward VI died at the age of 15. Dudley’s failed plan to change the succession and oust Princess Mary in favour of his daughter-in-law, the Protestant Lady Jane Grey, meant that by affiliation, William once again sailed into deadly territory. However, for a second time, he managed to emerge unscathed and, in the years to follow, would act out the role of a committed Catholic subject to perfection.

But how did Cecil and Elizabeth develop such a close connection? The seed of their friendship can be traced back to early in Edward VI’s reign, when Cecil, by now in his mid-late 20s, was appointed to manage some of the Princess’s lands in Lincolnshire. Clearly, they shared ground regarding their religious beliefs, and the pair began to correspond initially about business matters. However, the relationship flourished.

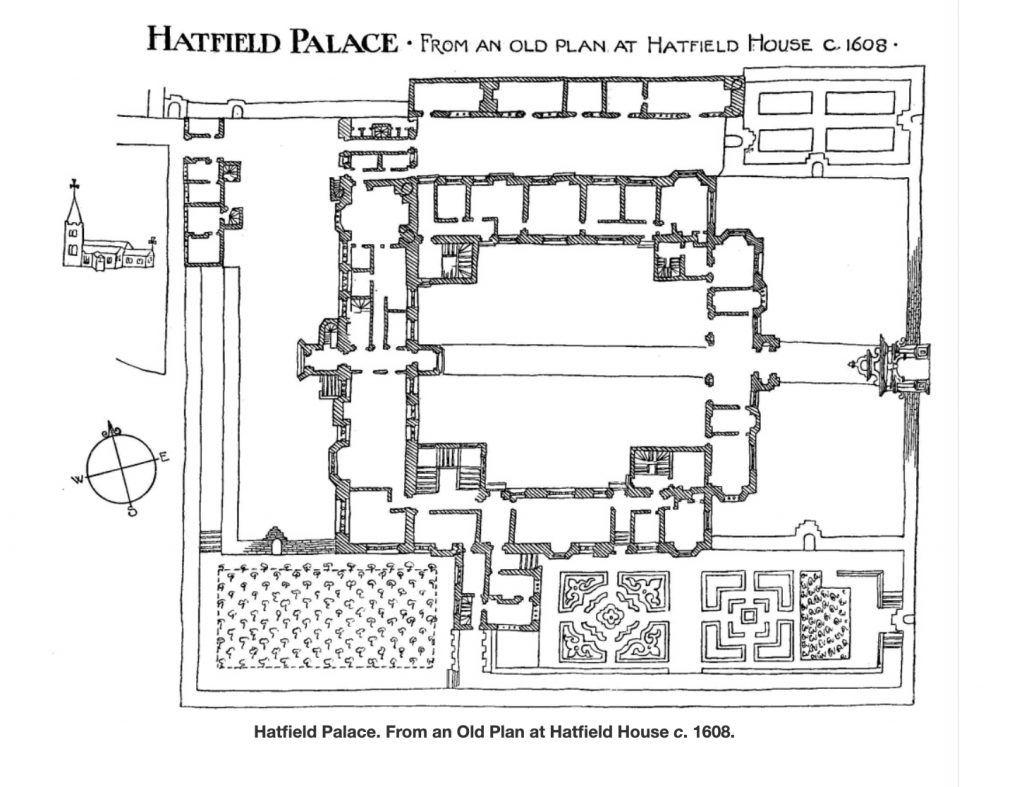

During the years of her half-sister’s reign, Elizabeth faced enormous uncertainty, and at times, her life was in extreme danger from those who wished to remove Mary’s Protestant heir. The worst came after the Protestant-led Wyatt Rebellion against Mary I, where Elizabeth was accused of involvement. The Tudor princess faced interrogation and potential charges of treason. She was imprisoned in the Tower before being released when nothing could be proved against her. Subsequently, Elizabeth spent six months under house arrest at the Palace of Woodstock before eventually being allowed to return to her home at Hatfield.

During this time, Cecil increasingly proved to be a reassuring, guiding hand, helping steer Elizabeth through a treacherous time in her early life. However, by 1558, the ground was shifting again- this time in Elizabeth’s favour. It was clear that all was not well with her half-sister. Mary I had lost Calais that year, been abandoned by her husband, Philip II of Spain, and endured a phantom pregnancy, whose symptoms were more likely due to Ovarian cancer.

Cecil visited Elizabeth at the Palace of Hatfield in February 1558. He likely discussed the need for patience and discretion, reassuring the queen-to-be that her time was fast approaching; he was certainly present when the new queen heard of her accession following the death of her half-sister on 20 November 1558. Upon his appointment, Harrington records in his ‘Nugae Antiquae‘ that Elizabeth spoke thus to her newly appointed first minister:

” I give you this charge, that you shall be of my Privie Counseille, and content yourself to

take paines for me and my realme. This judgement I have of you, that you will not be corrupted

with anie maner of guifte, and that you will be faithfull to the State, and that, without respect of my

private will, you will give me that counseile that you thinck best ; and if you shall know anie thinge

necessarie to be declared to me of secreasie, you shall shew it to myself onlie, and assure yourself I will not faile to keep taciturnitie therein. And thearfore hearewith I charge you. “

From that point forward, William Cecil was never far from the Queen’s side. He was immediately appointed Elizabeth I’s Secretary of State, becoming her first minister and the most powerful man in England. Theirs was a formidable relationship, and it is not the scope of this article to describe the challenges they overcame together, where they naturally aligned and where, sometimes, they clashed. However, if you wish to read more about their relationship, you can check out my blog, William Cecil And Elizabeth I: The Power Couple of the Tudor Age, in which I interview Elizabeth’s biographer, Professor Susan Doran.

However, for the rest of this article, I want to turn to the end of William Cecil, who was created 1st Baron Burghley by Elizabeth I in 1571.

The Death of Lord Burghley: Oh, what a heart have I that will not die!

By the summer of 1598, it was apparent to all that Cecil’s health was fading fast. That summer, Lord Burghley was based in Cecil House on the Strand. Throughout the sixteenth century, this main thoroughfare connecting the City in the east to Westminster in the west had been lined along the riverfront by the extensive houses belonging to the wealthy and powerful of Tudor England. Cecil House was one of those palatial houses. Across the summer, Lord Burghley was occasionally seen in his carriage or visiting his country house, Theobalds, just north of London.

A contemporary account from Lord Burghley’s chaplain, a certain ‘Mr. Thompson’ states: ‘His death was not sudden, nor his pain in sickness great, for he continued languishing two or three months, yet went abroad to take air in his coach all that time, retiring himself from the Court, sometimes to his house at Theobalds, and sometimes at London; his greatest infirmity appearing to be the weakness of his stomach; it was also thought his mind was troubled that he could not work a peace for his country, which he earnestly laboured and desired of any thing, seeking to leave it as he had long kept it.’

The enduring affection between Elizabeth and her subject, councillor and friend was evident. Driven by his unswerving commitment and fidelity to the last, William attended his last Council meeting in July, just 2 to 3 weeks before his death, and it is said that Elizabeth occasionally visited him at his London home.

I have come across two different accounts of Cecil’s final hours. The first reads:

‘He finally took to his bed late in July 1598, often tearfully wishing for death. At the end he called his children and grandchildren about him and took leave of them. As the hours went on after midnight, he said: ‘Oh, what a heart have I that will not die!’ and rebuked the doctor for trying to revive him. His last recorded words were, ‘The Lord have mercy upon me’, and about 7 o’clock in the morning of August 4th, he passed quietly away. ‘

…while a nineteenth-century biography of Cecil states:

‘For twelve days, the Lord Treasurer lay in his bed at Cecil House before he died, suffering but slightly, and resigned, almost eager for his coming release. On the evening of the 3rd August, he fell into convulsions, and when the fit had passed, “Now,” quoth he, “the Lord be praised, the time is come;” and calling his children, he blessed them and took his leave, commanding them “to love and fear God, and love one another.” Then he prayed for the Queen, handed his will to his steward Bellot, turned his face to the wall, and died in the early hours of the next morning; decorous, self-controlled, and dignified to the last.’

The Burial of William Cecil, Lord Burghley

The will that Lord Burghley handed to his steward survives. In one part of the will, Cecil describes his wishes for the disposal of his body. It is clear that his first wish was to be buried in his home town of Stamford and that a suitable place be made ready, which would also be fit for the burial of his grandfather, parents and ‘others who may succeed me’.

‘…have alreadie caused a place in St, Martin’s church in Stamford Barone in the countie of Northampton, wherein my house of Burleigh is situated, to be made fitt for a buriall place for the bodies of my grandfather, father and mother and my?elfe, and others that maie succeede me…’

However, he goes on to say that if his body cannot be buried there, then it should lie in Westminster Abbey, ‘near the bodies of my wife and daughter’ [Mildred Cooke and Anne, Countess of Oxford].

‘such as I shall in this my Will name, to take the charge of my buriall, to cause my bodie to be buried there; otherwise I will have it to be buried by their discretion with the licence of the Deane and Chapter in the collegiat church of Westminster neare where the bodies of my wife and my daughter of Oxford are buried.’

Cecil did not want to make a great fuss in death. Although he was given a state funeral at Westminster Abbey, with a parallel service being conducted at St Martin’s in Stamford, he requested that his corpse:

‘...be carried without anie pompe to my house of Burleigh in some coache covered with blacke, accompanied onelie with twelve personnes and noe mare, whereof fouer to be gentlemen and the rest yeomen and groomes…And that there be given fortie shillinges to everie parishe church for the poore where my corps shall remaine everie night, untill it shall be brought to my house of Burleigbe [Burghley], from whence it shall be decentlie carried to St. Martin’s church in Stamforde. And yet in hope of assured resurrection I will that such as I shall hereafter name shall burie it with convenient comelines according to the degree of a Baron and a Lord of parliament, and that the costs all manner of waies exceede not one thou?ande poundes, whereof one hundred poundes to be disposed at the tymes of the funerall to charitable uses...’

And thus, it was done. A service at Westminster Abbey was described in Stephen Alford’s online account of Cecil’s life as a ‘grand affair indeed’. The Calendar of State Papers for 29 August 1598 simply states: ‘Order of the funeral of Wm. Cecil Lord Burghley, High Treasurer of England, from his house in the Strand to Westminster Abbey, where it was honourably solemnized, and from whence afterwards his body was carried to Stamford, and there interred.’

However, John Chamberlain, writing the following day, says, “The Lord Treasurer’s funeral was performed yesterday with all the rites that belonged to so great a personage. The number of mourners were above 500, whereof there were many noblemen, and among the rest, the Earl of Essex, who (whether it were upon consideration of the present occasion or for his own disfavours), methought, carried the heaviest countenance of the company.’

An account by Henry Holland in his Herwologia Anglicana, written just 20 years after Cecil’s death in 1620, states that the coffin was set ‘in the midst of the choir, under a hearse adorned with eschuteons, penons and other ornaments, and there it stood six days, attended by heralds and other mourners; at the end of six days, a solemn service with the music of the Queen’s Chapel was privately performed for the deceased; whose body (being some few days before privately conveyed to Stanford) was there put into the vault on the same day that the said funeral was more pompously set forth at Westminster.

The Tomb of Lord Burghley

However, before we are done, I should highlight the conundrum outlined in Holland’s account above. State Papers record the service at Westminster Abbey on 29 August, while at the same time, the church register of St Martin’s states that Lord Burghley’s body was buried on the very same day – the 29th of August. It seems that a coffin was present at both. So, the question is, where was Cecil’s body? Westminster or Stamford? Since the church register records that Lord Burghley’s corpse was interred at Stamford on the 29th, we might think the body had been conveyed there some days before – as per Cecil’s will and Holland’s account above.

Lord William Cecil’s tomb is of typical grandiose, late Elizabeth style, with architectural features similar to those seen on the tomb of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and even that of Elizabeth I herself.

Fashioned from marble, pillars support an arched canopy, which bears Cecil’s heraldic crest and motto: Cor unum via una (One heart, one way). The heraldic shields of his wives, Mary and Mildred, are displayed on either side of his own. Taking centre stage is the elevated marble effigy of Lord Burghley. He wears armour (fashionable, but Cecil was certainly not a military man). However, over the armour, he wears his robes of state and carries his staff of office in his right hand.

I inquired whether Cecil is interred within the chest, upon which his effigy rests, or whether he is buried in a nearby vault. Apparently, the answer to that is unknown at present.

The only clue I came across comes in the account of Henry Holland, who speaks of Cecil being interred in a ‘vault’. Now, he could have been using language loosely. However, if we take his words at face value, it seems the body may well be nearby in an underground vault. Since a monument to his parents stands adjacent to Lord Burghley’s, but there is no such tomb chest associated with it, my money is on Cecil, his parents and possibly his grandparents being interred in a vault near the tombs/memorials under the floor of the side chapel.

Visitor Information

If you plan to visit the Cecil tomb, please check the latest opening times on the St Martin’s Church website. While you are there, be sure to stroll the road and enjoy some rest and refreshment at The George Inn, once owned by the Cecil family.

Other Locations Nearby

Burghley House: Lord William Cecil’s country seat on the edge of Stamford (2 miles).

Lyddington Bede: A property of the Bishops of Lincoln, visited by Henry VIII and Katherine Howard during the 1541 progress. The privy apartment of the bishop survives in an excellent state of preservation. A truly charming destination – not to be missed (14 miles).

Launde Abbey: An abbey which became the home of Thomas Cromwell after the Dissolution. Although Thomas never lived there, his son Gregory spent much time at Launde and was buried in the chapel there (20 miles).

Fotheringhay: The site of a Yorkist stronghold and birthplace of Richard III. Also, the place of execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (10 miles).

Peterborough Cathedral: The burial place of Katherine of Aragon and Mary, Quee of Scots, before the latter’s removal to Westminster Abbey (18 miles).

Sources

John Nichols’s The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth: Volume 3. 1533 to 1571

The life of that great statesman William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Secretary of State in the reign of King Edward the Sixth, and Lord High Treasurer of England in the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Published from the original manuscript written soon after his Lordship’s death; … To which is added, his character by the learned Camden, … With memoirs of the family of Cecil, faithfully collected … By Arthur Collins, Esq; 1732.

Politicians and Statesmen II: William Cecil, Lord Burghley (1520-98), by Stephen Alford. University of Cambridge.

The Great Lord Burghley: A study in Elizabethan statecraft, by Martin Andrew Sharp Hume. Published by James Nesbit & Co. London. 1898.

Calendar of state papers, Domestic series, of the reigns of Edward VI., Mary, Elizabeth, 1547-[1625], p 84.

Memoirs of the life and administration of the Right Honourable William Cecil, lord Burghley. Containing an historical view of the times in which he lived, and of the many eminent and illustrious persons with whom he was connected; with extracts from his private and official correspondence, and other papers, now first published from the originals, by Edward Nares, published by Saunders and Otley. London. 1828.

Letters Written by John Chamberlain During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. Ed. from the original by Sarah William. The Camden Society.