St Edmundsbury Abbey: The Life and Death of Mary Tudor

How much do you know about the life and death of Mary Tudor, Queen of France? Maybe quite a bit, maybe not. But what about Mary’s final resting place, St Edmundsbury Abbey, in Bury St Edmunds? This place of great wealth and beauty was dissolved in 1539, just six years after Mary’s body was interred in the abbey church.

Today, the abbey lies in ruins, Mary’s body having been transferred at the dissolution to the nearby church of St Mary. But what relationship did Mary have to the abbey during her lifetime, and what did the place of her burial look like in the sixteenth century? Let’s go time travelling and find out more about the magnificent St Edmundsbury Abbey and the life and death of Mary Tudor, Queen of France.

The Original Appearance of St Edmundsbury Abbey

Leland, the Tudor Chronicler, states that the ‘sun had not shone…on a monastery more illustrious’ than St Edmundsbury Abbey. He notes its ‘extent’, its ‘wealth’ and its ‘incomparable magnificence’. Some have claimed that St Edmundsbury Abbey exceeded ‘all monastic establishments in England, except Glastonbury’.

Image: © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Gateways and Great Court of St Edmundsbury Abbey

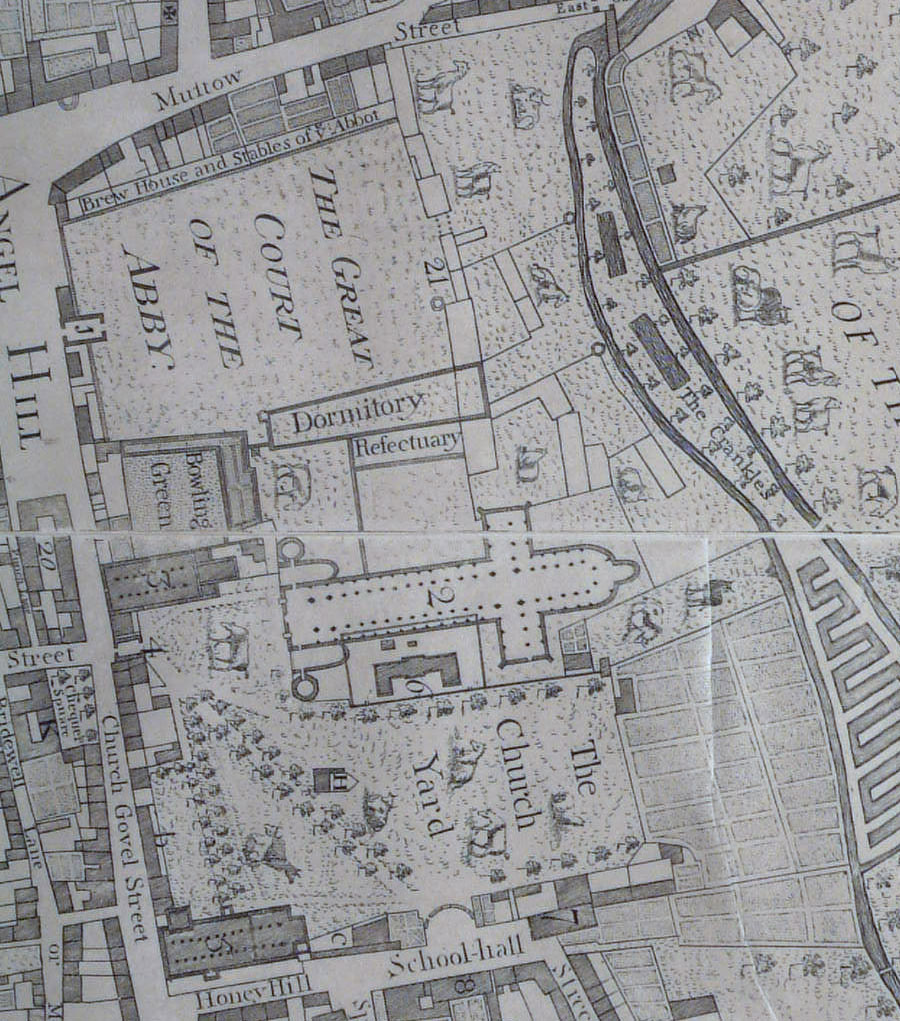

There were four entrances, or gateways, to the abbey, some of them made of bronze. Huge walls encircled the abbey compound, which Leland describes as being like a ‘town’ in scale and composition. These walls enclosed not only the mighty abbey church (see ‘2’ in the image above) but a fine abbot’s lodging (21) opposite the western gateway, three churches, a courtyard, garden and offices, as well as all the usual buildings associated with a great abbey.

The Great Western Gateway or Abbey Gate was the principal entrance to the monastery. Walk beneath its lofty stone walls. It opened into the Great Courtyard, in front of the Abbot’s Palace. This courtyard is significant in Mary Tudor’s history.

Following her return to England in 1515, whilst away from court, Mary lived at Westhorpe Hall. This was just around 15 miles away from the splendid county town of Bury St Edmunds. By this time, of course, she was married to Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk. The people of Suffolk were extremely fond of Mary. During the ‘great fair of Bury’ a pavilion was erected in the Great Court of St Edmundsbury Abbey, in front of the abbot’s lodgings (see both images above – a reconstruction – and below, for the appearance of this building). You can also see it clearly marked on the plan of the original layout of the abbey (above).

Image: © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The chronicler of unknown pedigree, who is recorded as reporting this, goes on to say that different gentlemen and nobility would travel from around to pay their respects to the French queen in her pavilion. It is easy to imagine what a colourful and joyful spectacle this must have been!

The Abbot’s Palace at St Edmundsbury Abbey

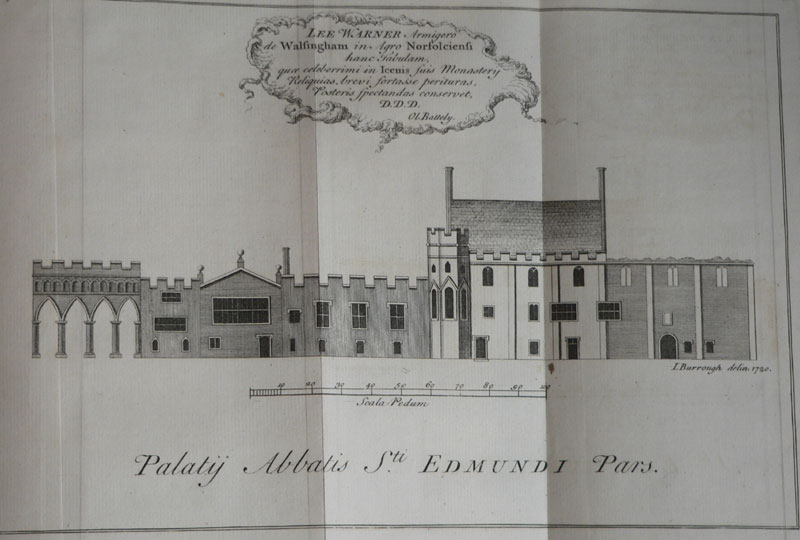

But what did Mary Tudor see when she looked out of her pavilion upon the Abbot’s Palace? Despite the dissolution, a substantial part of the abbot’s lodgings was left standing long after the abbey had been closed (which, by the way, was not an uncommon occurrence, c.f. Rochester, York and Dartford).

Image: © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The building was converted into dwelling houses that remained standing until circa 1720. From the History and Antiquities of the Abbey of St. Edmund’s Bury, we know that the walls were 5 feet thick, and there was a dining room that was ’55 feet long and 48 feet broad’. This chamber had 10 octagonal pillars with a tower in the northwest corner of the room (probably shown jutting out from the building in the image above). But by 1805, the building was in complete ruins with only remnants remaining.

The Norman Gateway and the Abbey Church of St Edmundsbury

Opposite Church Gate Street, and a little further along the perimeter of the abbey walls from the main Western Gate, was the Norman Gate (4). This gateway, which is also a stalwart survivor of the passage of time, opened up into a smaller courtyard, directly in front of the main west doors of the abbey church (2).

Walk under this gateway in your imagination. In front of you, rising up into the sky, is the western front of the abbey, with its main doors leading into the nave. The History and antiquities of the Abbey of St. Edmund’s Bury states that the western front was ‘particularly grand’. It had five doorways, the arches of which can still be seen today (see image below); a central tower and two octagonal towers at each end, both 40 feet in diameter.

Image: © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The abbey church was laid out in the conventional arrangement of a cross, and was just over 505 feet long; with the nave being 83 feet wide, and the transept, 264 feet. The body of the martyred St Edmund was laid to rest in the abbey in 1096, in a shrine at the eastern end of the church. For many generations, kings visited the shrine laying their crowns upon it – and retrieving them only upon the payment of large sums of money. You can see why Cromwell might have been able to make a case for corruption!

There were 17 altars in the church, with the main altar at the east end of the abbey church being dedicated to St Edmund. Having lain in state in the chapel at Westhorpe Hall for three weeks after her death on midsummer’s eve, 1533, Mary Tudor was finally brought to the abbey for burial.

The French queen’s lead coffin had arrived there at two o’clock in the afternoon of the 20 July. We might imagine the hearse, drawn by six horses draped in black cloth, passing beneath the Norman Gate before pulling up in front of the towering western edifice of the church. Once received by the Abbott, the coffin, draped in black cloth of gold and surmounted by a funeral effigy of the late queen, was taken inside the cool interior of the nave and placed in front of the high altar.

Image: © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The chief mourner was Mary’s newly married daughter, Francis Brandon, now Marchioness of Dorset. Her other daughter, Eleanor was also present, along with the Duke of Suffolk’s ward and soon to be wife, Katherine Willoughby. After the Mass was said, the nobility dined, one imagines, in the abbot’s lodgings as guests of the abbot himself.

The following day, Mary’s body was interred, although there does not seem to be any surviving record of where the tomb was located or what it looked like. Here lay Mary, resting peacefully beneath the vaulted roof of the abbey church until 1539, when the unthinkable happened and this great monastery was dissolved.

St Edmundsbury Abbey at its Dissolution

Although the abbot, and his monks, fought hard to preserve the abbey from ruin, it was in vain. Sadly, this great building did not escape the clutches of Thomas Cromwell and his henchmen. It was formally dissolved on 4 November 1539. One assumes that with her brother still alive, respect for his sister’s memory meant that Mary’s coffin was disinterred and her body reburied in the nearby church of St Mary, where it still rests to this day. A simple slab of stone reads, ‘Mary, Queen of France, 1533’. It is a little sad; a life so extraordinary, so meagrely remembered. However, she is not lost and for that, we can be grateful.

Further Information

To watch my video of Mary’s tomb in St Mary’s Church, follow this link.

For an account of Mary’s life read this by The Tudor Times. If you wish to read a more in-depth account of the death of Mary Tudor, click here for an article by Sarah Bryson.

Visitor Information

Suffolk is a wonderful county, full of historic medieval and Tudor treasures waiting to be explored. I urge you to plan a visit to this area, which takes in the ruins of this once mighty abbey, now resting in quiet repose amongst flower beds in the town’s Abbey Gardens.

A lock of hair belonging to Mary Tudor was taken from her grave after it was reopened in 1784; this can be viewed in the nearby Moyses Hall Museum, on Cornhill, just a few minutes walk away from the Abbey Gardens.

If you wish to spend a weekend exploring Bury, the abbey remains and surrounding areas, I can highly recommend the historic West Stow Hall, once home to Mary’s Master of the Horse, as THE place to stay.

Finally, if you want to enjoy a bit of history on a night out, why not walk around the abbey park at sunset then nip across the main square to the Angel Inn. There is a wonderful cocktail bar tucked away in a medieval, vaulted cellar. Very atmospheric!

Other places to visit in the area:

- Framlingham Castle and Church

- Long Melford Hall and Church

- Kentwell

Great post Sarah – I was at the abbey last week, the gardens are a peaceful place to remember Mary Tudor

Thanks Tony. They are rather lovely gardens, aren’t they? Shame we missed each other by a couple of weeks.

Loved this, another place to visit, thankyou so much and love the podcast too

Ooh, thanks for your comment about the podcast. More to come soon. Stay tuned. ????. So pleased you like the post. Thanks for letting me know. Sarah