Linlithgow Palace: The Renaissance Birthplace of Mary, Queen of Scots

Outside, a fierce winter terrorises the landscape. Scotland and the north of England lie covered by a deep blanket of snow, making the roads connecting the two neighbouring countries nigh on impassable. From time-to-time, hoarfrosts cast their magic across the countryside, leaving every twig and blade of grass glistening like a carpet of flawless diamonds in the bright morning sunlight. At night, fierce blizzards whip up the snow, dumping it in sculpted, icy dunes against the palace walls. But inside Linlithgow Palace, the many roaring fires keep the chill away and deep inside the queen’s privy chambers, a newborn babe is cradled in her mother’s arms.

The new heir to the Scottish throne was born on 7 or 8 December (usually cited as the 8 December) 1542, in the queen’s apartments at the majestic Linlithgow Palace, just 14-15 miles north-west of Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh.

Her mother was Marie de Guise. The Guises were a powerful French family at the heart of sixteenth-century France’s political, social and religious affairs. She had already been widowed and came to Scotland as the second wife of James V. Sadly, at the time of Mary’s birth, her father was a broken man. James had recently visited his wife following the devastating defeat of the Scots at the hands of the English at the Battle of Solway Moss. Following that defeat, he seems to have suffered some kind of mental breakdown, and he did not tarry long at Linlithgow Palace. Instead, he journeyed onwards towards another royal palace, his favourite, Falkland, where he took to his bed and died. His infant daughter was just six days old. Having lost two sons the year before, both of whom extraordinarily died on the same day, James was said to be devastated at the birth of a girl.

In the surviving English correspondence, a letter written from George Douglas to Lord Lisle seems to make very little of Mary’s birth, just that ‘the Scots’ queen is lighter of a daughter.’ Of course, Mary would soon become an ever-present thorn in the side of the English monarchy until her end came with her execution at Fotheringhay at the hands of her English ‘cousin’, Elizabeth I, some 45 years later, in 1587.

However, the road to Fotheringhay was long, and no one could have dreamt of such an eventuality as Marie de Guise passed that Christmas at Linlithgow. There was much to occupy her mind, though. The shifting sands of Scottish politics were dangerous. Furthermore, Henry VIII soon had his eye on Mary as a future wife for his own five-year-old son, Edward. But that was not Marie de Guise’s vision for her daughter. She wanted to unite France and Scotland in the ‘auld-alliance’. And so the stage was set for Mary, Queen of Scot’s extraordinary life.

In the coming months, I will be doing a great deal more research into the places associated with Mary, Queen of Scots. So, what better place to start than here, at Linlithgow Palace, the place of her birth and one of Mary’s mother’s favourite Scottish residences? What made Linlithgow so beloved by Marie de Guise, and what do we know of the rooms in which the little Queen of Scots was born? Ready to find out? Let’s begin our Scottish adventure!

Linlithgow Palace: A Brief History

Set about midway between Edinburgh and Stirling, Linlithgow Palace sits majestically elevated on a raised hillock adjacent to a beautiful inland loch. Described by one antiquarian as being surrounded by ‘lofty trees’, ‘sheltered avenues’ and ‘handsome pleasure grounds’, Linlithgow has long been associated with monarchy. The palace, which now stands in ruins, has a history stretching back at least as far as the Roman conquest of Britain. It was used by Edward I, ‘the Hammer of the Scots, ‘ during his occupation of Scotland in the late thirteenth century. However, the present building dates from the 1420-30s, having replaced the early medieval castle that was largely destroyed by two separate fires earlier in the fifteenth century.

King James I of Scotland can take the credit for commencing the building that we see today. He started the construction of a new palace at Linlithgow after he had been released from his captivity in England in 1424. Essentially, he established a ‘C’ shaped building with the main east-facing range containing a grand entrance passage running beneath a great hall, alongside north and south projections. From 1429, records refer to Linlithgow as a ‘palace’. Interestingly, it was the first documented palace that was purpose-built by a Scots king.

The building campaign at Linlithgow Palace was continued in the late fifteenth-century by James III. From building accounts, it seems to have been virtually finished by the time of James IV’s death at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513, when his wife, Margaret Tudor (sister of Henry VIII), is said to have waited in vain in part of the newly constructed west wing, (now known as ‘Margaret’s Bower’), for news of her husband’s return.

It was the construction of this west range that completed the palace, turning it into a quadrangular building, with four ranges enclosing a central courtyard. Within the centre of the courtyard was ‘a fine well, adorned with several statues; and constructed so as to raise the water to a great height’. The fountain was restored during the 1930’s and can still be seen in the courtyard today.

However, far from being a dour and draughty medieval castle, the construction of Linlithgow Palace was heavily influenced by a number of fashionable foreign trends in architecture, not least those of Renaissance France. Indeed, Marie de Guise herself is famously noted to have exclaimed that ‘she had never seen a more princely palace’ when she first laid eyes on Linlithgow. And let’s face it, coming from the utterly charming Renaissance palaces of the Loire, her standards would have been pretty high! All in all, the finished building, faced with polished stone, covered about one acre of ground.

The Queen’s Apartments

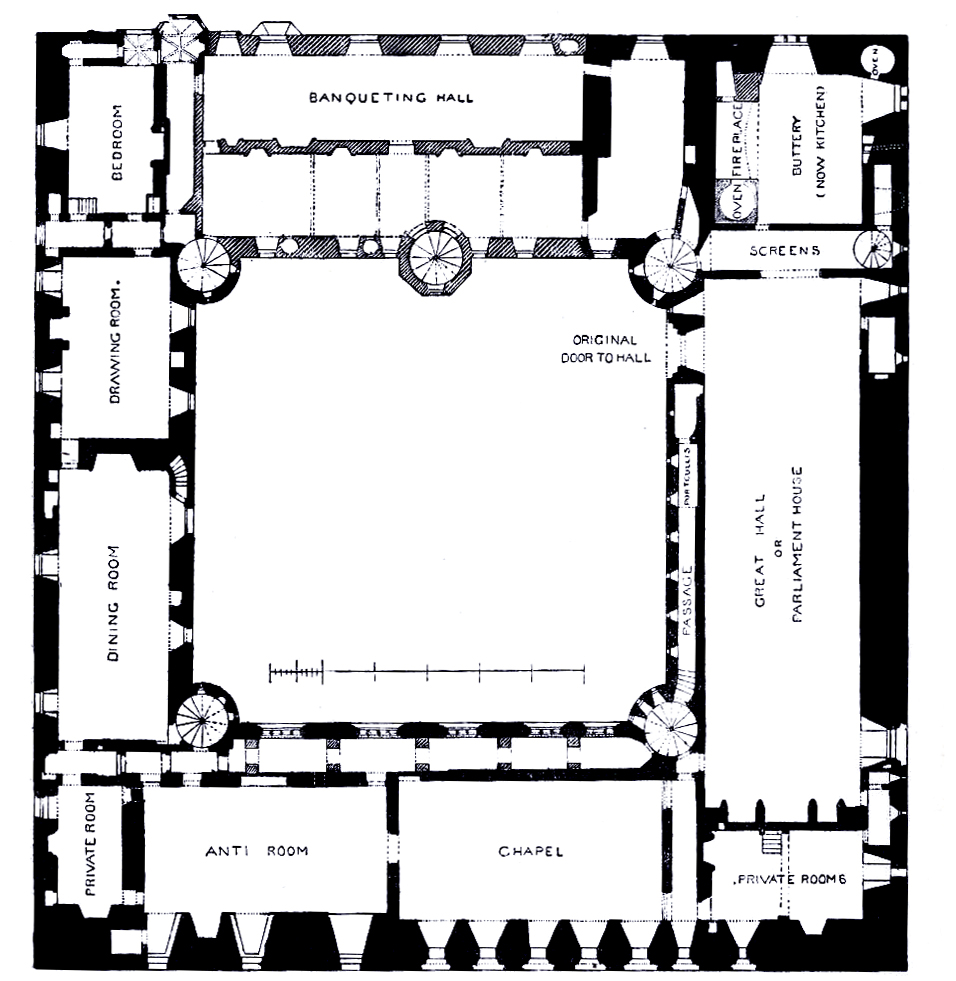

In building the west range, Mary’s grandfather, James IV, created a brand new set of privy chambers for both the king and queen overlooking Linlithgow Loch, with the king’s lodgings on the first floor (2nd floor to our US readers) and the queen’s on the third, or top floor. The floor plan above shows the usual kind of progression we associate with a high-status house of the day; a series of progressively smaller chambers which could be accessed by an increasingly restricted number of people. The queen’s bedchamber was at the far end of this sequence of rooms, in the north-west tower.

It was in this room that both Mary, and her father, James V, were born. Of course, here we have a lovely connection back to the Tudors. For James’ mother was Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, who had herself come to Scotland to be the Scottish Queen in 1503. Having written before about her sad farewell to her father and family at Collyweston, in Northamptonshire, it feels satisfying to pick up her story again here at Linlithgow, fulfilling the crowning glory of any medieval queen’s destiny: to provide a son and heir.

The room in which James and Mary, Queen of Scots were undoubtedly born could be expected to be one of, if not the, smallest chamber on the queen’s side. Having said that, it still measured fifty-one feet by twenty-one, and sixteen in height. So, still rather splendid!

In his Select View of the Royal Palaces of Scotland, Jamieson states that the bedchamber had ‘three doors communicating with it; and [it] does not seem to have been provided with grates, the fires having apparently been kindled on the hearths. On each side of this apartment is pointed out an Audience room or Hall, most probably what would now be called an Anti chamber. The carving in these rooms must have been very fine, but it is now much defaced.’

Following Mary’s birth, Mary de Guise did not stay long with her infant daughter at Linlithgow. Although she had entered into the Greenwich Treaty with Henry VIII, a treaty that would see Mary, Queen of Scots wed to the future Edward VI, she had no intention of honouring the agreement. With her eye on a French alliance, Marie wanted her daughter moved to the more secure royal fortress at Stirling. After an adept game of political shenanigans involving Henry VIII and his ambassador, Ralph Sadler, she managed to get the English to agree to the move under false pretences.

On 27 July 1543, Marie and her child made the journey to Stirling. This would become their home for the next four years until the five-year-old Mary sailed for France and towards her future destiny as Queen of both Scotland and France.

Next week, we will continue to follow in Mary’s footsteps and visit Loch Leven Castle, the place of Mary’s imprisonment following her surrender at the Battle of Carberry Hill.

Sources:

These are sources I found useful in writing this blog:

My Heart is My Own: The Life of Mary, Queen of Scots, by John Guy.

Scottish Royal Palaces: The Architecture of the Royal Residences During the Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Periods, by John G. Dunbar

The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII.

Linlithgow’s ‘Princely Palace’ and its Influence in Europe, by Ian Campbell.

Dear Sarah,

Thank you for a very good description of Linlithgow Palace, which I have only ever managed to see whilst driving past on the way to somewhere else. It is a great pity that it was wrecked in the eighteenth century.