Coronation Robes: Ritual, Tradition & Symbolism

Coronation ceremonies are elaborate ceremonial events that mark the accession of a new monarch to the throne and are laden with ritual, tradition and symbolism. Historically, marking the transmutation from human to sacred, a monarch enters their coronation as a worldly being. However, through the ceremony of anointing and coronation, God’s grace is bestowed, historically enabling the monarch to emerge transformed and reign in selfless service, loyalty and duty.

Like the ceremony and the space in which it occurs, the monarch’s coronation robes are imbued with meaning. The divesting of clothes and reinvesting with special robes after being anointed affirms the transition of the monarch’s body from that of an earthly being to one of a singular purpose.

The epitome of royal splendour, coronation robes are one of the most significant outfits a monarch will ever wear. To answer any questions you might have about the coronation robes, we have created this special blog. We will peel away the layers of the monarch’s coronation dress, exploring each layer’s purpose, and how the garments are commissioned, as well as investigating how the techniques used in creating these dazzling outfits compare to those used in Tudor times.

The Robes of Coronation

Four key items of clothing are worn at various times by the monarch during the coronation ceremony. These are described below:

The Robe of State

When a monarch enters Westminster Abbey at the start of the ceremony, they wear a robe known as The Robe of State, also referred to as The Parliament Robe. This ornate robe, made of crimson velvet and lined with ermine fur, is typically worn over the monarch’s coronation attire and is fastened with a gold clasp at the neck. Embellished with gold embroidery and adorned with symbols of the monarchy, The Robe of State is an important symbol of the monarch’s authority and power.

Shroud

The Shroud Tunic, known in Latin as the Colobium Sindonis, is a plain, white linen shift. It symbolises humility before God and the relinquishing of earthly vanities. Before the anointing ceremony, the Colobium Sindonis is placed over the monarch’s clothing (partly to protect the highly embellished expensive fabrics beneath from being stained by any errant drops of oil).

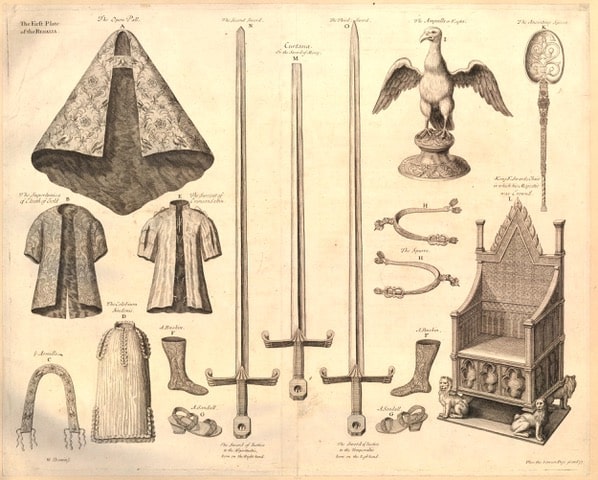

With the anointing complete, this linen shift is then covered by the Supertunica. Wearing these garments, the monarch takes their seat in the coronation chair before the Archbishop of Canterbury, England’s premier prelate, places the Crown of St Edward upon the monarch’s head and invests the King or Queen with the coronation regalia.

This done, the Colobium Sindonis and Supertunica are removed before the newly crowned monarch makes their final procession out of the abbey.

Supertunica

The Supertunica is worn during the investiture ceremony. The original medieval garment was passed down and worn by all monarchs until the Civil War but was destroyed during the interregnum. During that time, the gold or silver thread interwoven through the fabric was likely unpicked, and the remaining garment was probably destroyed.

However, this item was reinstated at the Restoration in 1660, and a new version was used at the coronation of Charles II in 1661. The Supertunica is a long robe made of golden silk and trimmed with golden lace. It is decorated with the symbols of the four nations of the United Kingdom: the rose for England, the thistle for Scotland, the daffodil for Wales and the shamrock for Northern Ireland. The Supertunica serves as a reminder of the monarch’s association with Christianity, drawing a parallel between priestly garments and royal attire.

The Robe Royal (Pallium Regale) is also worn during the investiture ceremony. This loose, cloak-like garment is worn over the Supertunica and is embroidered with national symbols and imperial eagles.

The Imperial Robe

The Imperial Robe is worn at the end of the ceremony for the monarch’s final procession from the abbey. Made from purple silk and trimmed with ermine, its design harks back to the imperial robes of Roman Emperors and is not to be confused with The Robe of State, which is the crimson velvet robe worn as the monarch enters the abbey.

The outer layer of this long gown features crimson velvet, lined with silk satin and a trim of Canadian ermine (fur from an ermine, a short-tailed weasel). The train of the robe features gold lace and filigree embroidery in the shape of wheat ears and olive branches, symbolising prosperity and peace.

Historical Sources

The earliest description of the robes to be worn by kings at their coronation comes from an inventory of 1356, while an account of the coronation of Edward III in 1327, when he was just 14 years old, describes how, after the King had laid aside the vestments of St Edward, he put on ‘two tunicles of red samite, a mantle of red samite garnished with emeralds and orient pearls, possibly a gorget of red samite worked with gold, a jewelled stole of red samite with gold lappets and two rochets of white silk’.

Roy Stong, who writes about this in his definitive guide to ‘coronation’, postulates that one was ‘likely to have been the garment in which he walked to the Abbey and the other the colobium sindonis, put on immediately after unction to prevent oil seeping through and damaging the historic vestments.’

Sadly, no items of coronation clothing have survived from before the English Civil War. However, thankfully, we have some additional records describing certain items worn by the medieval Kings of England. For example, at his coronation in 1399, Henry IV is described as appearing ‘aparelled lyke a prelate of the churche’, and in 1429, Henry VI is dressed ‘lyke as a bisshop should say masse with a dalmatyke and a stole aboute his nek’.

Alongside the inventory mentioned above, some of the earliest descriptions of what robes should be worn at an English coronation come from the Liber Regalis, written in the 1380s, during the reign of Richard II. This is essentially a medieval handbook of ‘how to do a coronation’! Amazingly, it survives and can usually be viewed in the Jubilee Galleries in Westminster Abbey. Alongside instructions for the ceremony, it speaks about items of clothing suitable for the event, including the Supertunica, which it describes as being ‘interwoven before and behind with great figures of gold’ and the four-cornered mantle as ‘interwoven with eagles all over’. The eagle symbolises harks back to the notion that the medieval Kings of England had regarding their Imperial right to rule.

Interestingly, it wasn’t just the robes of state that were valued and reused. On at least one occasion, the monarch’s dress was believed to be recycled from one queen to another. Of course, I am speaking of the gown worn by Mary I, England’s first Queen Regnant, at her coronation in 1553, and that worn by her half-sister, Elizabeth, five years later in 1558.

Research conducted by dress historian, Janet Arnold, looked at records relating to the commissioning of coronation robes by both women. In Mary’s case, a warrant survives that shows the Queen ordered a dress made of cloth that closely matches the description of the one Elizabeth is wearing in her iconic coronation portrait (see above). However, when Elizabeth was crowned five years later, no such commission was made; there was simply an instruction for the Queen’s tailor to amend an existing garment. While there is no definitive proof that the two half-sisters’ dresses were the same, the evidence is highly indicative of Tudor recycling!

Released under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

The Use of Cloth at Coronations

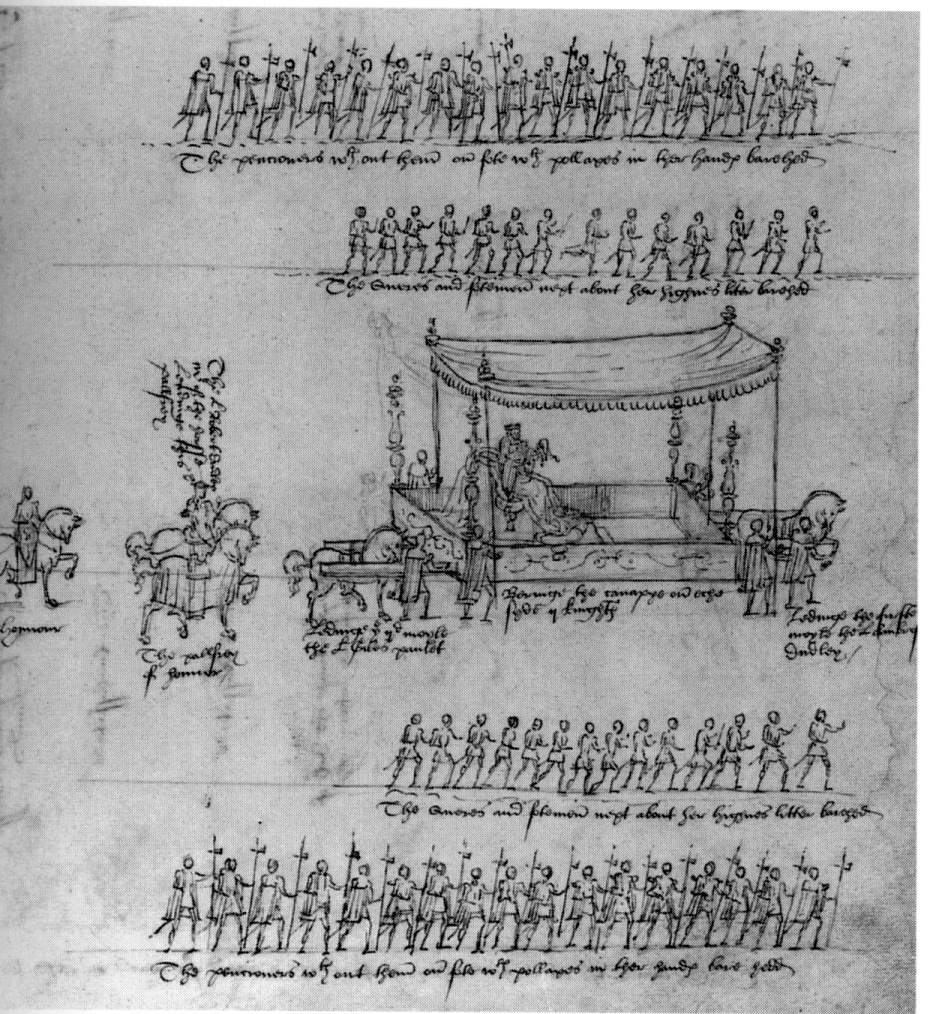

Alongside coronation garments, historically, cloth played a significant role in the visual spectacle of coronation, creating an added sense of grandeur and pomp that befitted the occasion.

Up to and including Charles II, traditionally, monarchs resided at the Tower of London in preparation for the procession through the City of London from the Tower to Westminster on the eve of their coronation. Often the King or Queen would wear shimmering cloth of gold, making them luminous and able to stand out in the crowd. Along the way, the streets would be decorated lavishly; houses were draped with tapestries and silks, while a succession of colourful pageants were staged en route.

The City spent vast amounts of money to ensure the streets were appropriately cleaned and adorned with luxurious cloth, including hangings, tapestries and banners. Surviving records enlighten us to the scale of that cost incurred; for Richard Ill and Anne Neville £3,124 12s ¾d; Henry VII £1,506 185 10¾d; and Henry VIII £4,748 6s 3d. This was a phenomenal amount of money at the time!

The Embroidering of Coronation Robes

As part of my research and filming for my summit, Your Essential Guide To Coronation: Unravelling the Mystique of Monarchy, I was lucky to visit The Royal School of Needlework at Hampton Court Palace, responsible for designing and creating Elizabeth II’s Robe of Estate in 1953.

The Head of Studio, Anne Butcher, showed me an example of how such garments are created, from design to the finished article. Remarkably, the techniques used for embroidering royal gowns today are astonishingly consistent with those used during the Tudor period. However, unlike today, most professional embroiderers during the sixteenth century were men. Surprisingly, it was a well-paid role that far outstripped the payments made to portrait artists of the day, such as the incomparable Hans Holbein. This underlines how esteemed and valuable cloth was deemed to be over some of the other trappings of wealth.

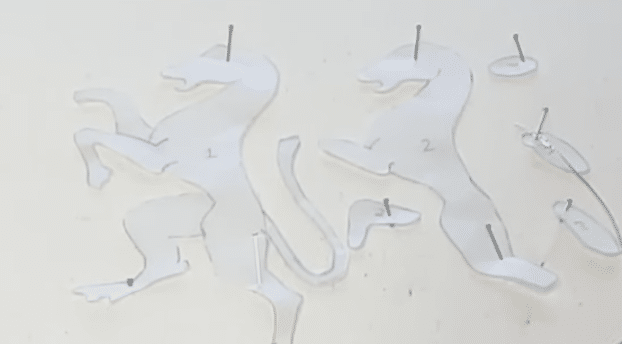

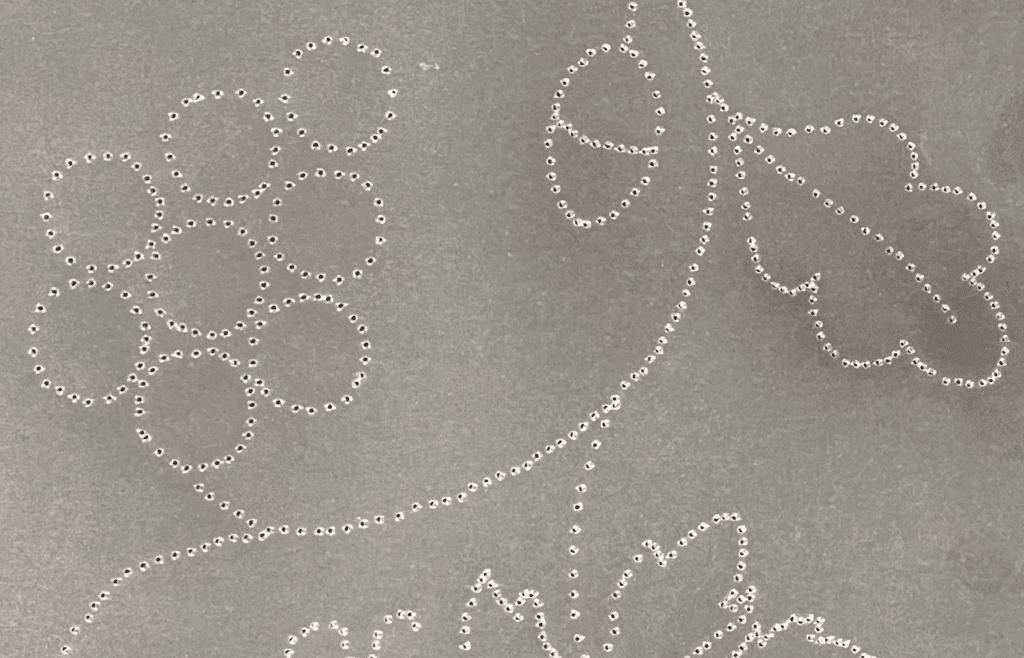

The pictures below show the various stages of creating a single embroidered motif. Like today, Tudor embroiderers would have worked on the garment using a trestle and frame, allowing the craftsmen to sit comfortably to work. Anne explained how the trestles could be small or extended up to four meters in length for larger pieces. Of course, this allows several people to work simultaneously on one project. The ability to scale up was critically important back in the sixteenth century when often there was very little notice of an impending coronation – perhaps just two or three months. The likelihood is that we must imagine the designers, tailors and embroiderers working literally around the clock and by candlelight to meet the looming deadline for coronation robes.

Below is a more detailed description of the stages, illustrated by a series of images in the gallery that follows…

Coronation Robes: Embroidery Fit for a King!

- Transferring design using prick and pounce: The design is traced onto the fabric, and tiny holes are made on drawn lines. A powder is pushed through the holes (called a pounce). As in Tudor times, charcoal or kaolin powders are still used today. Sixteenth century embroiderers left the lines unpainted. Today embroiderers often paint the lines using oil paint.

- With the design traced onto the fabric, the next step is to apply the padding. Padding can be built-up with carpet felt to create a sculpted, realistic shape. The padding is then stitched over to anchor it firmly into place.

- Next, the padding is covered with a smooth, woollen felt.

- Sewing over or through, the direction of stitching reinforces the shape. Tudor gowns were often worn in candlelight. The gold or silver thread picks up the undulation in the padding as well as catching the flickering candlelight to create a luxurious, ethereal look.

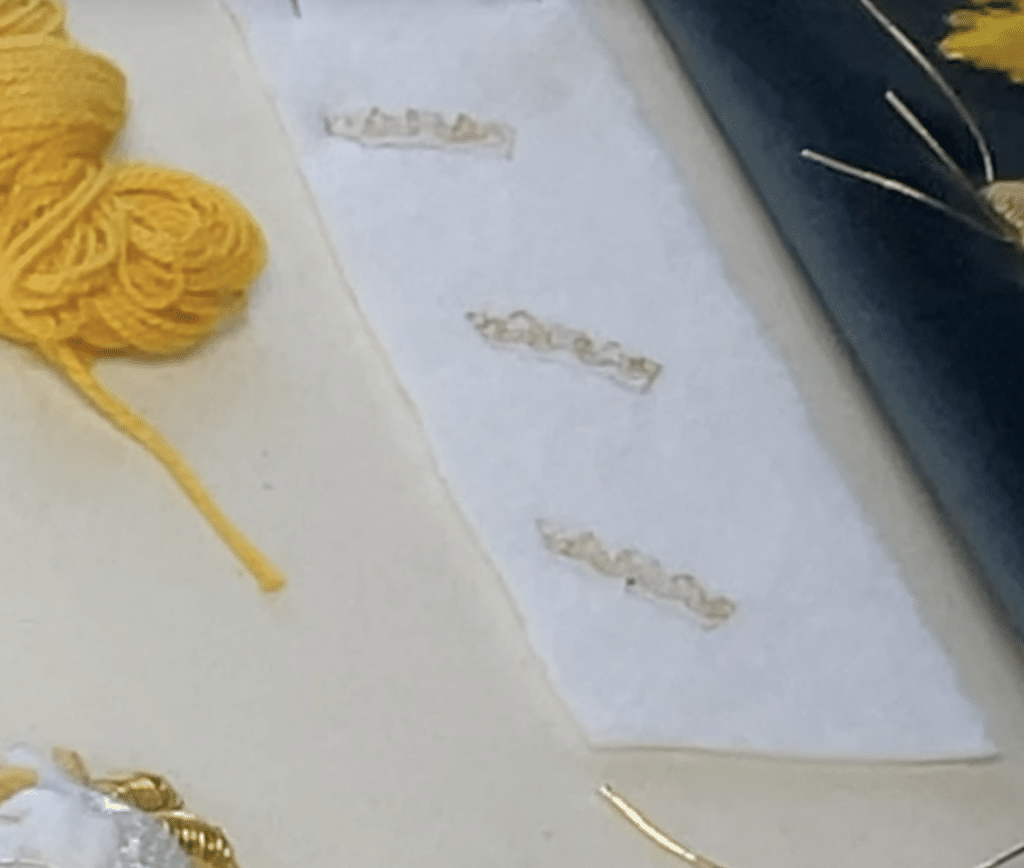

- For the silverwork, overstitching is completed using additional thread in non-metallic waxed silk or cotton. Called a ‘passing’, the beaten foil of metal is wrapped around a core (today of cotton, but likely silk in the sixteenth century). Stitched in pairs, the bricked stitches create a pattern and are a deliberate design feature.

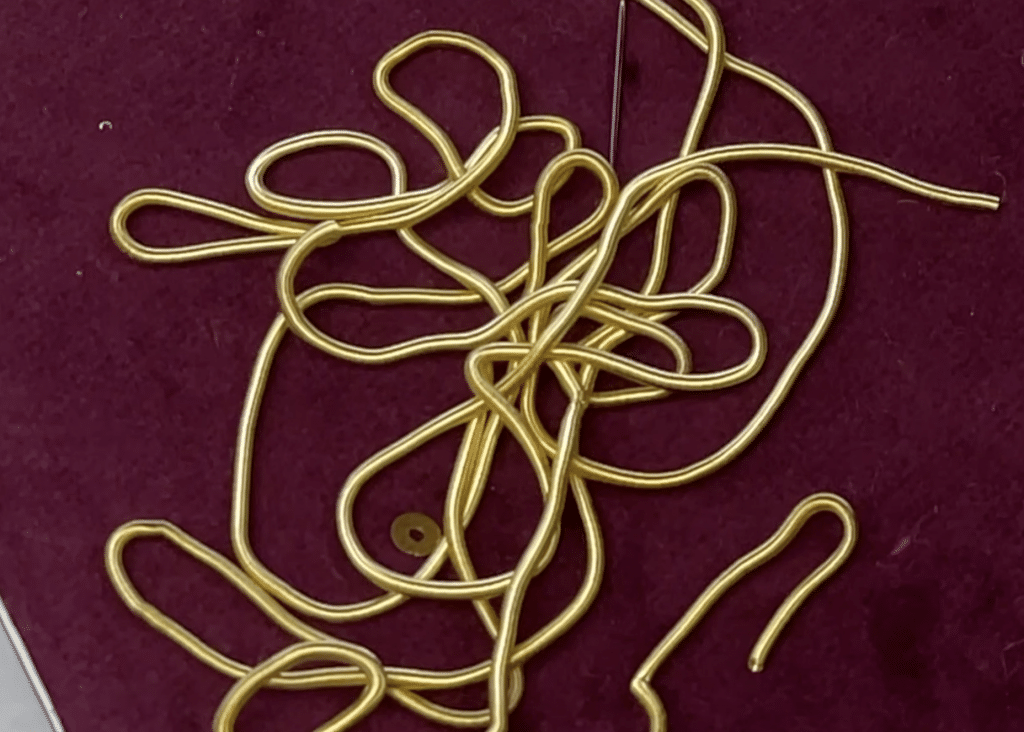

- For the goldwork, Bullion or Purl is used. Structurally, this is a very long spring and hollow at the core. It can be stretched apart slightly and couched between the wraps of wire or cut into short lengths and applied like beads. This thread comes in both shiny and matte versions; its spring-like structure lays over padding to catch the light,

An individual motif would take around 60-70 hours to complete. When Elizabeth II’s Robe of Estate was created for her coronation in 1953, the item took about 3500 hours to finish.

The Royal Family have released a first glimpse of King Charles III’s coronation robe – see it here.

Coronation robes are amongst the most glamorous and symbolic that a monarch will ever wear. Luxurious, dazzling and extremely expensive, their role as part of the coronation ceremony not only adds to the mystique of monarchy but, crucially, like everything else associated with the ceremony, historically reinforces the monarch’s transformation from mere human to God’s anointed to rule over the people of England. Will you be able to spot all the garments mentioned above on coronation day? Let me know in the comments below!

Sources & Further Reading

If you have enjoyed touching the past through this blog, you can join my membership, The Ultimate Guide to Exploring Tudor England, which brings together all my best, most comprehensive content in one place: blogs, videos, live chat, progresses, maps, itineraries, travel information and podcasts.

For more stories of royal traditions through time, check out this blog.

Coronation: A History of the British Monarchy by Roy Strong

Thank you Sarah! I prefer the gown of Elizabeth I. Also, I would be interested in hearing more about the ‘crown jewels’ the first Elizabeth wore to her coronation ?