A Tudor Ramble Around Rutland and Beyond

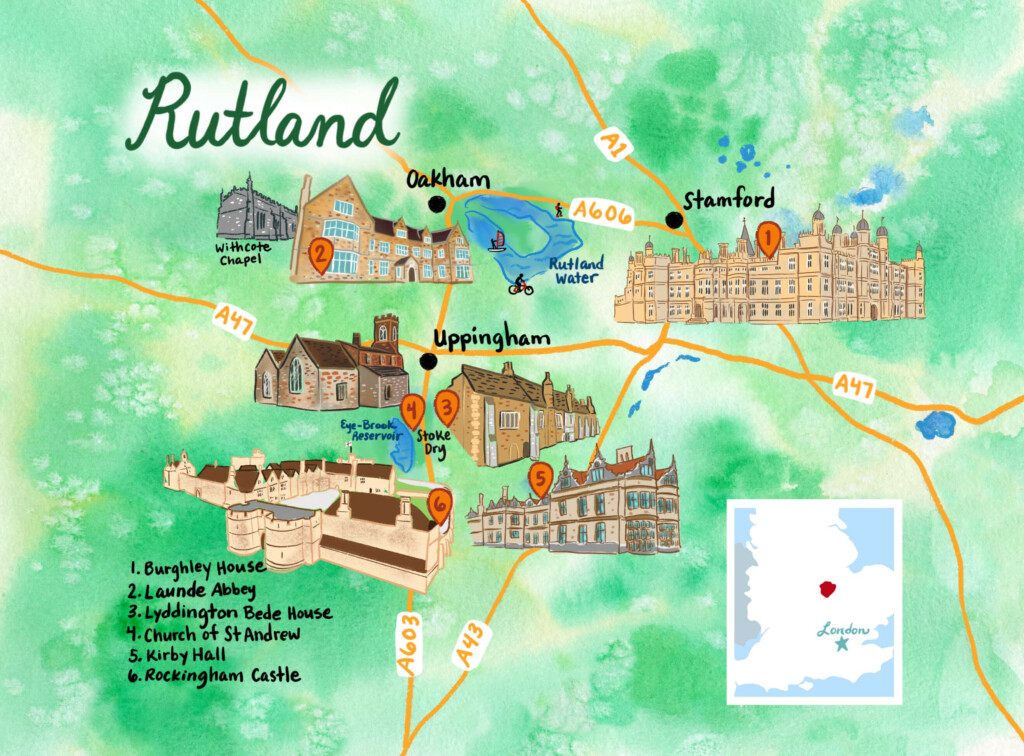

It is said that the best things come in small packages. This is undoubtedly true of Rutland, England’s smallest county. Rutland borders Leicestershire to the north and west, Lincolnshire to the north-east, and Northamptonshire to the south-west. Covering only 147 square miles, this rural county nevertheless boasts some glorious countryside, Rutland Water – England’s largest man-made lake, and a diverse and fascinating array of heritage locations. Also, because of its small size, a long weekend based in Rutlandshire allows us to cover four counties in one glorious long weekend of time travelling.

Indeed, inside and just beyond the county border, the curious time traveller can explore several historic locations with enticing links to the Tudor period. There is plenty to enjoy, from a grand prodigy house to a medieval bishop’s lodging that once hosted a visit from Henry VIII, from elaborate Tudor tombs to a deserted chapel that hides a rare Tudor treasure.

For this itinerary, we will base ourselves in the small market town of Uppingham, although I will offer some other tempting alternatives at the end of this article. Uppingham is renowned for its private school and quaint independent shops and cafes; it is also within easy reach of several of the locations included in this four-day guide. Hence, I have chosen it as a base for our travels.

So, let’s not dilly-dally. It’s time to go time-travelling!

Let’s go!

Itinerary

- Day One: Burghley House and Stamford, Lincolnshire

- Day Two: Launde Abbey and Withcote Chapel, Leicestershire

- Day Three: Lyddington Bede and St Andrew’s Church, Stoke Dry, Rutland

- Day Four: Kirby Hall and Rockingham Castle

Tudor Rutland: Day One

Burghley House and Stamford, Lincolnshire

Probably the most prepossessing and glamorous location in this four-day itinerary is the great Burghley House, built in the second half of the sixteenth century by Elizabeth I’s principal minister, William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Constructed upon the foundations of an earlier house and built on land acquired by his father, Burghley House rose like a phoenix alongside William’s own fortunes. In fact, Lord Burghley’s final phase of redevelopment started in 1573, just two years after his ennoblement, when his new-found status required further aggrandisement of the Cecil family’s country seat. More on this in a moment.

However, to understand Burghley’s significance to William, we must dig into the Tudor history of his ancestors, notably his father and grandfather.

Burghley House stands just a stone’s throw from William Cecil’s hometown of Stamford. Cecil was born in the nearby village of Bourne and maintained close ties with Stamford and the surrounding area all his life. His grandfather, David Cecil, had settled in the town in the latter part of the fifteenth century following a move from the Welsh / Herefordshire border, anglicising the family name around the same time from Seisyllt to ‘Cecil’.

This patriarch of the Cecil dynasty set the family on the road to the top of Tudor society by ingratiating himself with the founder of the Tudor dynasty, serving Henry VII as a yeoman of the King’s Chamber. He also became a freeman of Stamford in 1494 and owned the famous George Inn in the town centre. This sizeable coaching inn played host to royal visitors and still stands today, retaining much of its medieval and Tudor charm.

Cecil’s loyalty to the Tudor crown paid off when he obtained a place for his son, Richard, to serve the new king, Henry VIII, as a page of the Royal Chamber. It was shortly after Richard’s return from serving the King at the Field of Cloth of Gold in 1520 that his eldest son, young William Cecil, came into the world. Incidentally, this was also the same year that Richard secured the land (by marriage) upon which Burghley House now stands.

Little William was schooled in nearby Grantham, and this early education was followed by a period of undergraduate study at Cambridge University, where the future Lord Burghley studied law. However, it was during the second half of the sixteenth century, at the accession of Queen Elizabeth I, that William Cecil’s fortunes began their inexorable rise. Appointed on the first day of Elizabeth’s reign as her Principal Secretary, he served his queen with loyalty and devotion for over 40 years until he died in 1598.

But what about the Burghley House we see today? Rewind to 1553, when William Cecil came into his patrimony. By this time, he had already established himself in the elite ruling class of Edward VI’s protestant regime and was clearly wealthy enough to remodel the house his father had begun. However, as mentioned above, after 1571, Cecil deemed the building he had been working on was of insufficient stature to reflect his exalted status. Thus, between 1573 and 1588, yet another round of construction completed the magnificent prodigy house that visitors still admire today.

A visit to Burghley and William Cecil’s splendid tomb in St Martin’s Church, Stamford, is a must for any Tudor history lover, given he was the most pre-eminent statesman of the Elizabethan age. However, I feel obliged to end with a word of caution. If you expect the interiors of Burghley House to shimmer with Tudor furnishings and treasures, you may be disappointed. Unfortunately for the dedicated Tudor time traveller, Burghley was subject to sweeping interior redesign in the eighteenth century. This has left us with staggering Baroque interiors, but tragically, there is virtually nothing of the luxurious rooms Lord Burghley would have known. Well, I suppose you can’t have everything in life!

Burghley House – Burghley House, Stamford, Lincolnshire, PE9 3JY

Tudor Rutland: Day Two

Launde Abbey and Withcote Chapel, Leicestershire

‘Myself for Launde’: These words were written in Thomas Cromwell’s own hand as part of the Lord Privy Seal’s private ‘Remembrances’. The note is dated April 1540 and marks the availability of Launde Abbey following its dissolution the previous year.

Until the dissolution of the monasteries, Launde Abbey was an Augustinian monastery founded in 1119. When you visit Launde today, it is easy to see why Thomas Cromwell fell for its charms. Of course, the original abbey is long gone, swept aside by later redevelopment. Still, its situation, nestled in the bottom of a gently sloping valley, which extends away to the front of the house like a natural amphitheatre, is idyllic. When the antiquary John Leland passed by Launde in 1540, he recalls Launde as ‘one of the fairest houses in Leicestershire’ and to have ‘one of the fairest orchards and gardines’.

There are records of Cromwell visiting Launde in the years before its closure as a religious institution. One amusing anecdote comes in a letter dated January 1532. The Canon of Launde writes to Cromwell, reminding him that ‘when ye lay with us here at Launde Abbey some time, ye would take the pains to walk with me or my brethren about our business, and as you and I came one day from Withcoke [Withcote] I had a fall backwards in the snow at a place called the Dammes, between Launde and Withcoke.’ It was during these visits that Thomas must have taken a shine to Launde and its inestimable charms.

Unfortunately, Cromwell was never able to enjoy his new Leicestershire home. He was arrested just two months after making the above note, on 10 June 1540, and executed shortly thereafter. However, his son, Gregory, inherited the estate and converted the monastic buildings into a comfortable family home. Over the generations, more modifications were made, such that the house we see today can best be described as an extensively modified Elizabethan manor house. The chapel where Gregory Cromwell is buried is considered the only significant remains of the original Tudor manor.

After being given to the Diocese of Leicester in 1957, Launde Abbey was turned into a Christian retreat centre, and the chapel remains a place of worship. However, you can walk through the park. A fabulous little coffee shop is located on-site and is open to the public. If you wish to visit the Tudor chapel and see Gregory Cromwell’s memorial stone, you must ask permission at reception. Bear in mind that this might not be possible if the chapel is in use.

While visiting Launde, I urge you to follow in Cromwell’s footsteps and make the relatively short journey to nearby Withcote Chapel. Withcote is an early sixteenth-century chapel built to serve the adjacent Withcote Hall. Its location is isolated, and as the chapel is now redundant, you will likely be alone as you pick your way along the dishevelled and overgrown footpath towards the chapel’s entrance.

It is an eerie place; time has taken its toll on the building, which is ‘at risk’ and urgently needs repair. Much of the interior was remodelled in 1744 when the embattled parapet and the corner pinnacles were added to the exterior. However, a scarce set of Tudor stained glass windows, dating from 1530 to 1540, has survived. The workmanship has been attributed to Gaylone Hone, Henry VIII’s master glazier, making the windows of even greater interest.

Withcote Chapel is a few minutes’ drive by car from Launde Abbey. Alternatively, if you are feeling a little more adventurous, a public footpath leads you across the Leicestershire countryside between the two sites; this might make for a delightful 3.5-mile round trip on a pleasant day.

(Note: If you are unlucky enough to find the chapel closed, a key is held at Launde Abbey, which you can request. Therefore, if you are walking from Laude to Withcote, check in at the reception in Laude and take the key with you.

Launde Abbey – Launde Road, Launde, Leicestershire, LE7 9XB

Withcote Chapel – Withcote, Oakham, Leicestershire, LE15 8DP

Tudor Rutland: Day Three

Lyddington Bede and St Andrew’s Church, Stoke Dry, Rutland

2-3 miles south of Uppingham is the tiny, picture-perfect Rutlandshire village of Lyddington. At its heart lies Lyddington Bede, the remnants of a much larger palace that once belonged to the powerful Bishops of Lincoln. While the building incorporates several fascinating features, it can also stake its place in Tudor history as a location visited by Henry VIII and Katherine Howard on their 1541 progress to York.

Lyddington was one of several palaces and manors owned by the medieval bishops of Lincoln. At the time, this diocese was the largest in England, extending from the River Thames in the south to the Humber Estuary in the north. Thus, it covered around half the country’s length. Like other manors belonging to the bishopric, Lyddington lay on a significant thoroughfare; therefore, the palace was a convenient location for the bishop and his entourage to lodge when traversing the diocese and travelling to London.

Although large parts of the original manor have been lost, today’s building contains the bishop’s public and private rooms, including the impressive Great Chamber with its intricately carved ceiling cornice. It is one of a kind and is a delightful find. Even stripped bare of its interiors, visitors can clearly see the flow of a high-status sequence of rooms from the aforementioned public ‘Great Chamber’ through a series of successively smaller spaces used privately by the incumbent bishop and his closest attendants, friends and guests. By the way, I would postulate that as these were the most luxurious rooms at the palace, they were probably used by Henry VIII during his brief sojourn at Lyddington.

The Cecil family acquired the palace after the Reformation and transformed it into their family home. At the turn of the seventeenth century, Thomas Cecil, 1st Earl of Exeter and the son of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, converted the old palace into an almshouse for twelve poor bedesmen. It served this function for just over 400 years until 1930. It is now under the guardianship of English Heritage.

The serenity of this much-overlooked historic property makes Lyddington Bede one of my favourite locations in Rutland. The village is quaint, and there is a lovely English pub down the road from the old palace where you can enjoy lunch after looking around the remains of this once-important building. A real find!

While in the area, you may want to visit the nearby village of Stoke Dry, where you will find a handsome Tudor porch or ‘parvis’ (def. A chamber over a porch reserved for the parish priest), a fifteenth-century rood screen and a Tudor chest tomb of Sir Edmund Digby (d. 1590) and his wife; the tomb is embellished with beautiful carvings of their many children, including babies who died in the first few months of life. They are depicted in their swaddling garments and are called ‘chrysoms’.

Lyddington Bede – Blue Coat Lane, Lyddington, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE15 9LZ

St Andrew’s Church – Oakham, Leicestershire, LE15 9JG

Day Four

Kirby Hall and Rockingham Castle, Northamptonshire

‘Haunting’ is the word I would use to describe the first destination on our final day of this itinerary. Although Kirby Hall lies abandoned and mainly in ruins, these ruins are substantial. Its isolated location, palatial proportions, elaborate architecture and immaculate gardens speak to its glorious past. Yet, somehow, all this only accentuates the eerie spectre of the hall’s gaping windows, doorways and roofless ranges now graced only by raucous rooks and majestic peacocks. It’s almost as if the owners left and simply forgot to return.

Kirby Hall is considered one of the finest examples of an early Elizabethan prodigy house. However, unlike Burghley House, whose exterior is said to have been modelled on the appearance of Richmond Palace, Kirby has an entirely different and distinctive look, with the owners clearly having an eye on the very latest designs of the day. Consequently, Kirby Hall’s layout is based on French architectural pattern books of the time, while early seventeenth-century renovations embellished the hall with lavishly applied classical features. These latter features are particularly prominent on the facades of the impressive inner gatehouse and the porch that leads into the Great Hall.

The house was built in 1570. Unfortunately, its owner, Sir Humphrey Stafford of Blatherwick, did not live to see its completion. Shortly after his death, in 1575, Sir Humphrey’s son sold Kirby Hall to Sir Christopher Hatton, one of Elizabeth I’s favourites and Lord Chancellor of England. He completed the house, although it remains unclear exactly how much time Sir Christopher spent there. Still, a letter dated 1580 makes it evident that he took his time to visit his sparkling new country house because he wrote to a friend that he was going ‘to view my house at Kirby, which I have never yet surveyed.’

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Kirby Hall is a double-courtyard house with a large outer courtyard, which is unremarkable except for the gatehouse range, embellished during Inigo Jones’ classical revival of Kirby Hall in 1640. From the outer courtyard, the gatehouse hints at the architectural glories that lie beyond inside the smaller, inner courtyard. This is by far the more spectacular of the two.

Passing through this gatehouse range into the inner courtyard reveals Kirby Hall’s full splendour. Alongside the northern gatehouse range, the visitor can admire the east and west ranges, which once contained connected guest and family apartments. The latter also features a first-floor gallery; at over 100 feet long, it is celebrated as one of the longest in England.

The hall was abandoned in the 1800s. Lead was stripped from the roof, wainscot panelling was removed, and the local population spirited away stone to complete their own building projects. Subsequently, nature gradually encroached on the ruins, and curious visitors left lingering accounts of deserted rat-infested hallways and ‘nettle-decked passages’. That was until Kirby Hall was rescued in the 1930s, when its owner, the Earl of Winchelsea, placed it in the care of the State.

Today, Kirby Hall is managed by English Heritage. While much of the hall remains in ruins, part of the southern range survives. Stripped naked but otherwise intact, this fragment of the hall was refitted and redecorated to authentic seventeenth—and eighteenth-century designs. The visitor can explore a complex of staterooms, beginning with the Great Hall and including the old library and Great Chamber, before wandering through the well-tended, southwest-facing gardens.

Having concluded our visit to Kirby Hall, we need to travel 4.5 miles westwards to just north of the small industrial town of Corby. Our final destination on this itinerary is a visit to a 950-year-old medieval castle, once cherished as a hunting lodge by its royal owners.

Rockingham Castle was built on the orders of William the Conqueror shortly after his successful conquest of England. At the time, the area was surrounded by the Forest of Rockingham, and William selected the site of the present castle as both an administrative centre and hunting lodge. The castle was much-loved by its early Plantagenet royal owners. Edward I poured money into creating a lavish palace, including developing the distinctive bulbous towers that frame the castle’s gatehouse, which still survive today.

However, Rockingham’s last use as an administrative base for the Crown was in the late fourteenth century. By the Tudor period, the castle had fallen into such a state of significant disrepair that Henry VII built a hunting lodge in the park as an alternative accommodation. Henry VIII and Katherine Howard were the last royal visitors to the castle. The couple stayed there during the same 1541 progress that took them to nearby Lyddington Bede. Such was the sorry state of the building by this time that Henry VIII saw fit to lease it out to Edward Watson, who began converting the medieval castle into a comfortable, contemporary family home. Thus, the current building reflects the architectural blending of the early medieval walls encompassing later Tudor ranges.

Situated on a hillside with a splendid view over five counties, Rockingham Castle is the perfect final destination to reflect on all you have seen throughout your travels. So, while Rutland may be the smallest county in England, in its small size lies its great beauty, allowing the time traveller to traverse the border into three adjacent counties with ease.

Kirby Hall – 2 Kirby Ln, Deene, Gretton, Corby NN17 3EN

Rockingham Castle – Rockingham, Corby, LE16 8TH

Accommodation:

Uppingham

If you want accommodation recommendations and prefer a hotel option, why not try The Falcon Hotel, a sixteenth-century coaching inn in the centre of Uppingham? It’s a popular choice with all the town’s facilities at your fingertips.

Alternatively, if you prefer a self-catering option, this highly rated privately rented apartment, again in Uppingham, might be just the ticket.

Kirby Hall

If you want something a little quirky and would like to opt for something more remote, then Peacock Cottage at Kirby Hall is worth a look. Although the accommodation is modern, you can wander around the ruins and gardens after general admission has closed. That would be quite something!

Stamford

If you have deep pockets, I couldn’t leave out the historic ‘The George of Stamford’. Located virtually opposite the church where William Cecil is buried, you will follow in royalty’s footsteps if you choose this as your place to stay.

Rutland Water

If you love the outdoors, you will want to combine your history with a visit to Rutland Water – a very popular destination for outdoor pursuits, both on and off the water. You might even wish to stay close to the water’s edge. If so, try the five-star Hambledon Hall or, alternatively, Rutland Hall, which is a slightly cheaper alternative and has an impressive range of alternative accommodation options.

Further Reading

You can listen to my on-location podcast from Launde Abbey here and view the associated show notes page here.

You can listen to my on-location podcast from Rockingham Castle here and view the associated show notes page here.