A Long Weekend In The Tudor Welsh Marches

Today, we follow a Tudor trail that meanders north to south through an area once known as ‘The Welsh Marches’. This was the border area between England and Wales, comprising the counties of Cheshire, Shropshire, Herefordshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire. It was infamous for its lawlessness and, in the sixteenth century, was still ruled over by powerful Marcher Lords on behalf of the English Crown.

On this occasion, we remain on the English side of the border, traversing three of the counties mentioned above. We travel around 90 km from the picture-perfect Stokesay Castle in the north to the ancient manor of Hellens in the south. There’s plenty of history to enjoy along the way, from the haunting chantry chapel of Arthur Tudor to the haunted corridors of one of the oldest domestic houses in England, through lush pastures and bustling cities, from a county that gave birth to the Industrial Revolution to one that gave the world and the famous Worcester sauce. Are you ready for your next adventure in time?

Let’s go!

Itinerary

- Day One: Stokesay Castle and Ludlow, Shropshire

- Day Two: Kinlet and Worcester Cathedral, Worcestershire

- Day Three: Great Malvern and Little Malvern Priories and Hellens Manor, Herefordshire

Tudor Marches: Day One

Stokesay Castle, Shropshire

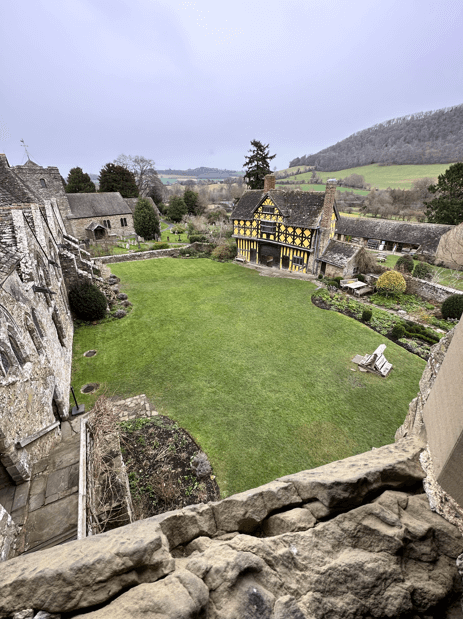

When you visit Stokesay Castle, you could be forgiven for thinking that the building had stepped off the set of a Disney fairytale. While Stokesay was probably never intended as a serious fortification, its diminutive medieval stone hall and towers, along with its striking seventeenth-century timber-framed gatehouse, all encircled by a dry moat, make it one of the most eye-catching and distinctive castles in England.

Stokesay’s origins date back to the Saxon period, before the Norman invasion of England in 1066. However, it was Laurence of Ludlow (1250-1294), a wealthy wool merchant of the Welsh Marches, who was primarily responsible for constructing the building we see today.

To use a modern turn of phrase, Laurence was ‘minted’ from trading wool derived from the Marcher lands with Continental Europe. After purchasing the tenancy of the castle in 1281, Stokesay became Laurence’s base in the area, a luxurious family home close to the heart of his business operations.

Stokesay Castle.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The rebuilding of the earlier castle took five years to complete and was finished in 1290. Sadly, Laurence died only four years after taking up residency; he drowned off the coast of England in 1294, presumably during one of his forays abroad.

During the Tudor period, Stokesay began to be known as a ‘castle’, possibly after the pretentious aspirations of its sixteenth-century owners: the Vernon family. They had their sights on an elevation to the nobility. However, instead, it seems that the patriarch of the family, Henry Vernon, ended up in trouble when someone for whom he was standing as surety defaulted on their debt. Henry was committed to Fleet Prison in London, and eventually, he was forced to sell Stokesay Castle in 1598 to cover his substantial debts.

One of the remarkable features of Stokesay is that it is one of the country’s finest surviving fortified manor houses, with much of the castle dating back to the late thirteenth century. Its authenticity makes it easy to discern the typical medieval arrangement of a ‘Hall House’: a great hall attached to a single-family living chamber, known as the solar. At Stokesay, two tower blocks flank each extremity, known as the North Tower and the South Tower. These structures provided extra high-status accommodation on the upper floors, with glorious views across the Shropshire countryside.

Today, the castle’s interior features mainly date to the original house, including a thirteenth-century wooden staircase leading from the low end of the Great Hall to the North Tower. However, the gorgeous decorative wooden panelling in the solar dates from the seventeenth century, as does the memorable ochre-coloured gatehouse.

English Heritage manages Stokesay Castle, and if you are looking for tea and cake to accompany your dose of history, you will not be disappointed, as there is a satisfying cafe onsite.

From Stokesay, it is just a nine-mile journey to visit a popular site of Tudor pilgrimage: Ludlow and its eponymous castle.

Ludlow, Shropshire

Ludlow Castle was built by the de Lacy family shortly after the Norman conquest. It is an imposing structure perched on a rocky promontory overlooking the River Teme. Its importance to Tudor history lovers lies primarily in the fact that on 2 April 1502, Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales and heir to the Tudor throne, died at Ludlow Castle, likely due to an infectious disease. The young prince had been married for a matter of months to the princess from Spain, Katherine of Aragon.

After death, Arthur’s body was embalmed, and his heart was removed and buried at the nearby parish church of St Laurence’s. When you visit, look out for a plaque inlaid into the chancel floor near where Arthur’s body lay in state. After three days of obsequies, the body was removed and taken for burial at Worcester Cathedral.

To explore the castle, you will first pass through the twelfth-century gatehouse. This opens out into a substantial outer bailey that occupies an area of almost four acres; it once housed stables, storehouses, and workshops.

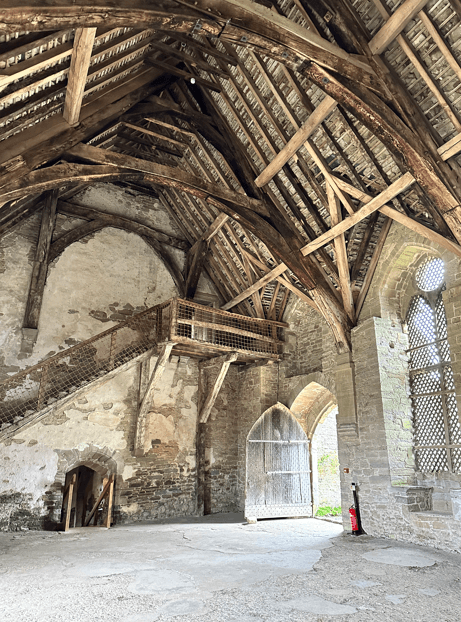

As usual, the inner bailey contained the privy apartments at the castle and was reached by passing through the arched entrance of the inner gatehouse, sited next to the original Norman keep. Across the inner courtyard from this gatehouse stands the residential range. This was built along the castle’s curved curtain wall. Begun in the late thirteenth and completed in the fourteenth century, these high-status buildings were palace-like in their magnificence. They comprised a series of interconnected buildings, including a three-story solar block, an adjoining Closet Tower, a magnificent great hall, which in 1684 was said to be ‘very fair’, and another three-story residential block, sometimes referred to as ‘The Great Chamber Block’, or ‘Upper Chamber Block’.

Ludlow Castle.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The rooms used by the most high-status residents were located on the upper storey of the Solar Block, accessible directly from the adjacent great hall via a spiral staircase or a staircase on the ground floor. During his sojourn at the castle, Prince Arthur occupied these lodgings and almost certainly died in these rooms.

Today, the apartments are an empty shell; the roofs and floors are gone. The exposed stone walls, some covered in moss and lichen, look bleak, and it is hard to see how Ludlow Castle could be viewed as palatial. However, it most certainly was in its day; the configuration of rooms into private suites heralded the latest in residential fashion for the aristocracy of the medieval period.

And so, today’s time-traveller must reimagine its splendour; the walls plastered, covered in the rich hues of finely carved oak panelling, with expensive tapestries hung thereabouts, the chambers warmed and brought to life by the flames dancing in the hearths of the many open fireplaces.

Today, Ludlow Castle is privately owned and open to the public for most of the year. However, opening times vary seasonally, so please check their website for details. If you are planning a visit and are a committed ‘foodie’, you may want to coincide your visit with the town’s famous food festival. It is usually held in the castle grounds in September and champions ‘local and seasonal food & drink from the Marches region’.

Tudor Marches: Day Two

Kinlet

Our next location is deliciously adrift from any well-worn tourist trail. We leave the bustle of Ludlow behind to delve deep into the lush Shropshire countryside to visit an isolated spot that was once the country seat of the Blount family. They rose to prominence because of Henry VIII’s affair with Bessie (Elizabeth) Blount. The beautiful one-time mistress of Henry VIII became mother to his illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, later the Duke of Richmond, in 1519.

Kinlet is a place that Bessie would have been familiar with. She grew up alongside her ten younger siblings at the Blount’s principal country seat of Kinlet Hall. Sadly, the hall Bessie knew is gone, but the adjacent parish church of St John the Baptist survives.

Surrounded today by rolling fields, you would probably not think of visiting this remote building, which, from the outside, does not look particularly remarkable. However, inside the church is a Tudor treasure trove! One medieval and three Tudor tombs span a century of family history. These include the Tudor tombs of Bessie’s parents, Sir John and Lady Catherine; her grandparents, Sir Humphrey and Lady Elizabeth; and her irascible brother, George.

The Blount tombs in the parish church of St John the Baptist, Kinlet.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Of the first two, the tomb of Bessie’s parents is probably the most interesting as Bessie features as one of the weepers on the side of the tomb chest. This is a rare depiction of Mistress Blount, whose likeness has otherwise been lost to time. Take along a torch to illuminate this dark corner of the chancel to try and make out Bessie’s name inscribed on the scroll to the right of her head, although the letters are only faintly visible.

While the monuments to Bessie’s parents and grandparents are of the typical tomb-chest type, with reclined effigies lying on top of a stone chest, the one commemorating her brother is an altogether different, more grandiose affair. This is the magnificent memorial to Sir George Blount, younger brother of Bessie Blount, and his wife. As a tomb, it is a tour de force of Elizabethan design and fashion, punching way above its weight for the small parish church in which it is located.

Sir George was born around 1512 or 1513. He inherited his father’s estates in 1531 and was knighted in 1544, spending most of his working life serving the Crown and being a member of Parliament. Unfortunately, George does not seem to have been as amiable as his sister and was generally disliked by all, including his wife. She filed for a legal separation, which was successful sometime before October 1575.

From Kinlet, we have a 21-mile journey south to pick up the story of Prince Arthur in the City of Worcester.

Worcester Cathedral, Worcestershire

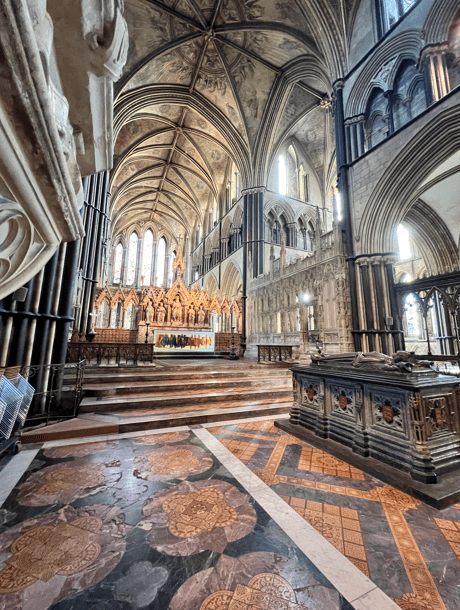

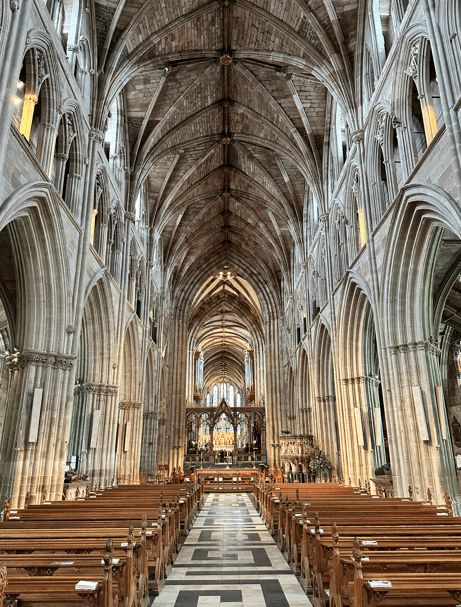

Like Ludlow, Worcester is firmly on the Tudor trail because of its cathedral, which is the final resting place of Prince Arthur, the one-time heir to the Tudor throne. His death in 1502 was a catastrophe for his parents and ultimately changed the course of English history. The cathedral is fascinating and includes the tomb of an English king and a copy of the Magna Carter. However, we will concentrate on its Tudor treasures.

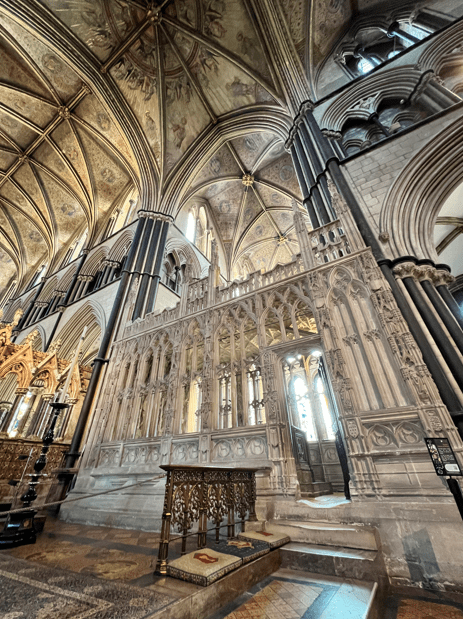

Prince Arthur’s tomb and chantry chapel lie south of the cathedral’s high altar, with the chapel finally being sanctified 14 years after Arthur died at Ludlow. The worn step which gives entry to the chapel is a testament to the countless generations of people who have visited and prayed at this tomb, including that made by his niece, Queen Elizabeth I, in 1575.

The chapel is undoubtedly a glorious symphony of late medieval architecture, full of Tudor heraldry. It is also a profoundly moving place to visit, as so many ‘what ifs’ swarm about you as you run your fingertips across the marble lid of Arthur’s beautiful chest tomb. It’s mind-boggling to think, ‘What if Arthur had lived to be king…?’

Enigmatic questions aside, the interior and exterior of the chantry chapel are a feast for the eyes; it is covered in heraldry and symbols of the Tudor dynasty, from the royal coat of arms at one end of the tomb chest to the 19 carved stone panels on the exterior face of the chapel’s south side. Arthur’s royal lineage and noble descent from the Houses of Lancaster and York are emblazoned for all to see.

Worcester Cathedral.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Included on those 19 panels are the Prince of Wales ostrich feathers, the Beaufort Portcullis, a single Tudor rose, the rose en soleil and the eagle and fetterlock (previously a Yorkist badge adopted by Henry VII). You might also want to see if you can spot the pomegranate of Granada (for Arthur’s wife, Katherine of Aragon), the arrows in a cluster (for Katherine’s father, Ferdinand of Aragon) and the fleur-de-lis (for Prince Arthur’s great-grandmother, Katherine de Valois and France).

Finally, while viewing the chapel’s exterior from the south side, turn around to find another chest tomb in the centre of the south transept. This is the tomb of Griffith ap Rhys, fashioned from Purbeck marble. Griffith was a mighty Welsh knight who was born circa 1470. He rode at the head of Prince Arthur’s funeral procession in 1502 and would later continue to serve at court, including attending Henry VIII at the ‘Field of Cloth of Gold’. He died shortly thereafter, in 1521, at the age of 51.

While in Worcester, you might want to explore two other interesting Tudor buildings of note: Greyfriars, a restored fifteenth-century merchant’s house and The Tudor House Museum. Both can be found close to the cathedral, on Friar Street, once part of Worcester’s medieval centre.

Having completed our visit to Worcester, we continue southwards to find two rare artefacts located within two Worcestershire Priories.

Tudor Marches: Day Three

Great Malvern and Little Malvern Priories, Worcestershire

Great Malvern Priory was once a thriving abbey associated with the diocese of nearby Worcester. It was dissolved, as almost all religious institutions in England were, in the 1530s. What remains is the priory gatehouse (which became part of a private dwelling) and the priory church, which now functions as the parish church in the spa town of Great Malvern.

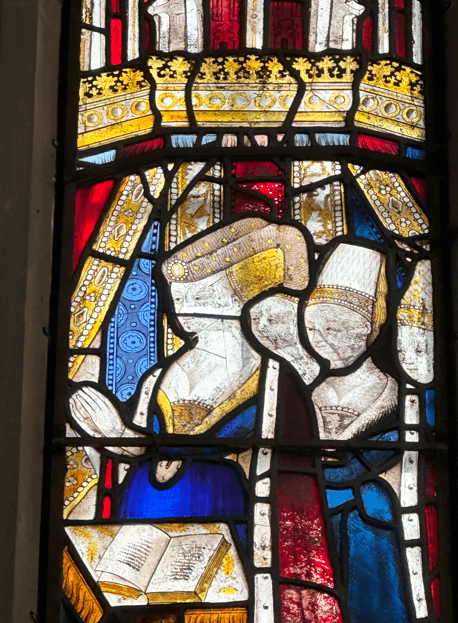

However, some 30 years before the Dissolution, in around 1501, a stained glass window was placed on the north side of the priory church. It apparently once showed Elizabeth of York alongside her husband, King Henry VII, and a rare depiction of their eldest son, Prince Arthur. Sadly, the image of Elizabeth is lost, but those of her husband and son remain. Three other Tudor nobles are also shown: Sir Thomas Lovell, Sir Reginald Bray and Sir John Savage.

Sometimes, you hear that this window was created on the orders of Henry VII. However, I have read that the more likely explanation is that these noblemen were the patrons, with Henry giving his assent to their images appearing alongside those of the royal family. It is thought that the window was probably placed there to commemorate Arthur’s ‘coming of age’ following his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. Of course, as we have already heard, the celebrations were short-lived, as Arthur died unexpectedly in the Spring of 1502.

Stained glass window in Great Malvern Priory.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

While there, you will also want to check out the tomb monument to John Knotsford (d 1589) and his wife. Knotsford was a Sergeant-at-Arms to Henry VIII. He bought the Prior’s house and associated land six years after the dissolution of the Great Malvern Priory. It is primarily thanks to his patronage that the church, and particularly its medieval glass, survived. I adore the life-size, kneeling figure at the foot of the tomb. This is Anne Savage, who funded this splendid monument in memory of her parents.

Before you leave the area, consider travelling four miles south of Great Malvern to the tiny village of Little Malvern and the remains of its priory, where another historic and rare late-medieval artefact awaits you.

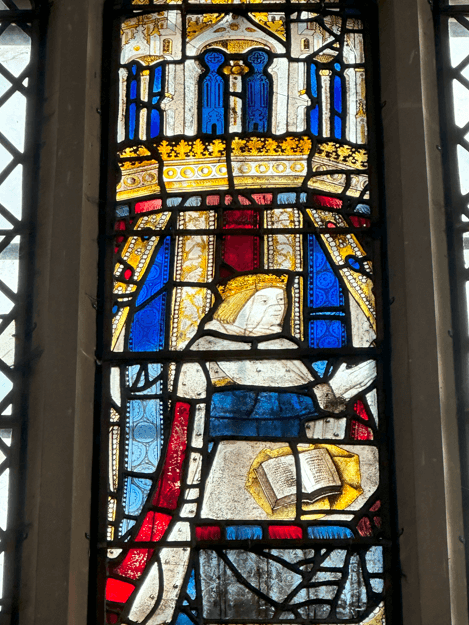

Little Malvern Priory was a Benedictine monastery from 1171 to 1537. Only a fragment of the original abbey remains, including part of the twelfth-century church, rebuilt in 1480–1482. The present building comprises a medieval chancel and crossing tower, along with a modern west porch situated on the site of the east bays of the nave. The transepts and the two chapels flanking the choir are in ruins.

One of the medieval treasures of the priory is the remains of a stained glass window at the east end of the church, above the high altar. Although only fragments survive, two historic window panes are still intact. One depicts Elizabeth Woodville and her eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, kneeling directly behind her. The faces of two of Elizabeth’s younger siblings can also be seen. Then, in the second complete panel, is Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward V, of course, famously one of the lost Princes in the Tower. This is an incredibly rare image of the Prince. The only other window showing the House of York (in a similar way to this) can be found in Canterbury Cathedral.

This window has been accurately dated to 1480-2. No one knows why it was placed in such a small and seemingly unimportant religious house. One explanation might be that its patron, Bishop William Alcock, was Chancellor of England and president of the Royal Council. Its placement in the priory was likely a simple homage to the reigning monarch.

Hellens Manor, Herefordshire

For our final visit, we cross into Herefordshire to visit a house reputed to be one of the oldest in England. It is undoubtedly steeped in around 1000 years of history, with royal connections that span several centuries. Today, Hellens remains privately owned; its architecture encompasses Tudor, Stuart and Georgian elements, although its foundations date back to the twelfth century.

Its medieval history boasts connections with William the Conqueror, the hated Roger Mortimer, the lover of Queen Isabella, a granddaughter of Edward I, and Sir James Audley, boon companion and military adviser to Edward, the Black Prince.

Despite its illustrious connections, it was considered ruinous when the Walwyn family inherited Hellens in the early fifteenth century. Thus began a process of renovation and modernisation using new-fangled brick fashioned from clay extracted from a nearby pond. The legacy of these renovations remains distinctly visible in parts of the building today, with the courtyard being completed in 1451.

Hellens Manor

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

If you are partial to a spot of ghost hunting with your history, then Hellens does not disappoint. The house has seen its fair share of drama and misery, from bodies buried under floorboards to a young girl locked in a room and kept in solitary confinement for around 30 years until she took her life at age 50. Her crime? An elopement that went disastrously wrong, forcing the girl to throw herself upon the mercy of her, as it would turn out, merciless family. There have been numerous reports of spine-chilling coldness in parts of the house that are said to be haunted by these spirits.

Other Tudor highlights include a room named after Mary Tudor, where legend has it that she once slept, and a cabinet of artefacts that features a steel and ivory dressing case, said to have once belonged to Anne Boleyn. While this is hearsay, there are certainly portraits of some of Anne’s near-relatives: Henry Carey, her nephew and his granddaughter, Philadelphia, said to be holding her great aunt’s comb. If you want to read more about these artefacts, I have a guest blog on The Tudor Travel Guide site, which was researched and written by Sylvia Barbara Soberton.

Hellens is known for its events, including its annual garden and music festival. The house closes for the winter at the end of September / early October and opens around Easter. During the summer, it is open on Wednesdays, Thursdays, Sundays, and Monday afternoons during the bank holidays. Entry is by guided tour. More details can be found on their website here.

Further Reading

You can listen to my on-location podcast from Hellens Manor Abbey and view the associated show notes page here.

You can listen to my on-location podcast from Worcester Cathedral and view the associated show notes page here.

You can listen to my on-location podcast about the Blounts of Kinlet and view the associated show notes page here.