5-Day Itinerary: London

If you are visiting London, have five days to spend, and are wondering about some of the most fascinating Tudor places you might explore, then look no further! I have curated some of my personal favourite locations to uncover. While some are essential bucket-list destinations, others are well-hidden or largely off the usual tourist trail. However, they are all steeped in Tudor history and will surely satisfy your craving for some intensive Tudor time-travelling.

While the first two days cover off what I call ‘the BIG three’ must-see locations, days four and five will lead you further afield to explore some lesser-known Tudor-themed places. However, if you need extra inspiration, I am including a link to download my ‘Tudor London Made Easy Guide‘. This highlights 17 locations in London with links to Tudor history, adding a couple more destinations not mentioned below.

I have also included the map below, so that you can see the spatial distribution of the following locations. Let’s go time travelling!

Your Itinerary:

Day One: Westminster Hall & Abbey and the Tower of London.

Westminster Abbey is the first of my ‘Big Three’ Tudor hotspots in London. Head to the City of Westminster to visit Westminster Abbey and Hall in the morning. I strongly recommend arriving at the Abbey early, before it opens. This way, you will have the chance to get ahead of the crowds, which can be substantial, even out of the usual high summer tourist season. January and February are the best times to visit if you are trying to avoid crowds.

If you arrive well ahead of time, remember that the Cellarium Cafe, associated with the Abbey, opens at 8 am. This is 1.5 hours ahead of the Abbey opening time of 9.30 am (Monday-friday) and one hour ahead on Saturday when the Abbey opens at 9 am. The Abbey is closed to tourists but open for services on Sunday. You access the cafe outside the abbey’s opening hours via Dean’s Yard.

Do book your entrance tickets to the Abbey ahead of your visit. It can save you substantial time queuing at peak times. Also, I recommend, at the very least, booking a ticket to the Jubilee Galleries to view some of the most treasured artefacts in Westminster Abbey’s possession, including the funeral effigies of Henry VII, Elizabeth of York and Mary I. There is also Elizabeth I’s corset (from her funeral effigy) and a prayer book of Margaret Beaufort. From the Galleries, you can also see the most spectacular views of the priceless Cosmati Pavement, the choir and the nave. Remember, this is where Henry VIII would have watched Anne Boleyn’s coronation from behind his ‘latticed screen’!

You might also want to book onto the Abbey’s ‘Hidden Highlights’ tour. This hour-long guided tour takes you behind the scenes to visit places that otherwise are not open to the public, such as the Jerusalem Chamber and the medieval library. These can get booked up well in advance, so make sure to plan well ahead of your intended travel dates.

Before we go, here are some ‘must sees’ that are sometimes overlooked:

- Must-Sees:

- The tombs – the most difficult to find is that of Edward VI, as it is a plaque on the floor near the tomb of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. If you want to read more about some of the royal Tudor tombs at Westminster, click here and here.

- The Coronation Chair – This is located in a glass-fronted area, adjacent to the west doors. Edward I commissioned it to hold a stone called the Stone of Scone, captured from the Scots in 1296 (returned 1996). The chair is made of oak. It was initially covered in gold leaf and decorated in coloured glass. The lions at base date from 1728.

- Anne of Cleves tomb – This is to the right of the high altar. The tomb is unfinished and easily missed. See the connection between the tomb and my involvement in the discovery of the Anne of Cleves Heraldic panels here:

- Don’t forget to visit the cloisters, the pyx chamber (where the Crown Jewels were stored in the medieval period), and the chapter house.

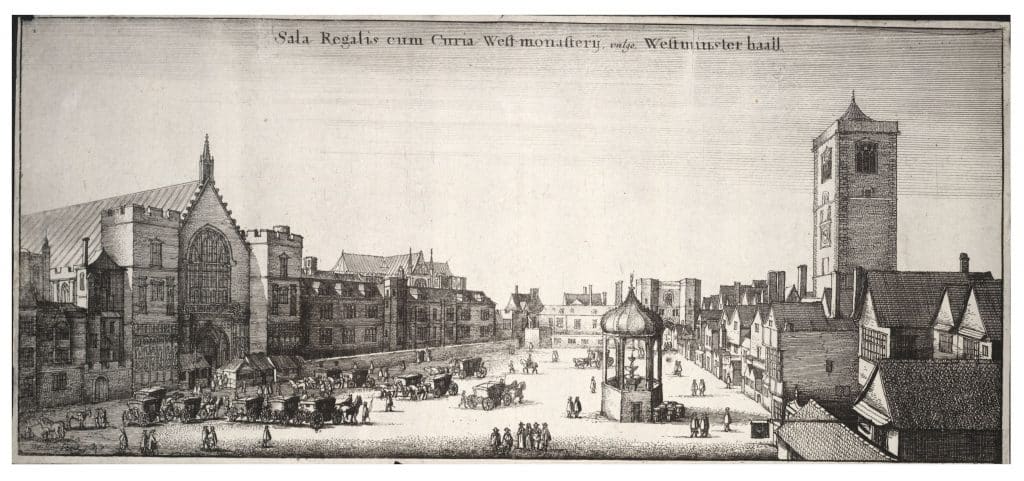

Across from the Abbey are the Houses of Parliament, the seat of the United Kingdom’s government. Before visiting the Hall, you might want to check out two further historical sites along the way. The first is St Margaret’s Church, which sits directly adjacent to the south side of the Abbey. it was built during the reign of Henry VIII in 1523. Two famous burials to look out for Wenceslaus Hollar (who drew the fantastic Tudor cityscapes of London) and Sir Walter Raleigh.

Next, head behind the east end of the Abbey to find the Jewel Tower. Besides Westminster Hall, The Jewel Tower is the only survivor from the old medieval Palace of Westminster. As the name suggests, it was built in the 1360s as a secure store for royal treasure within the private palace of Edward III.

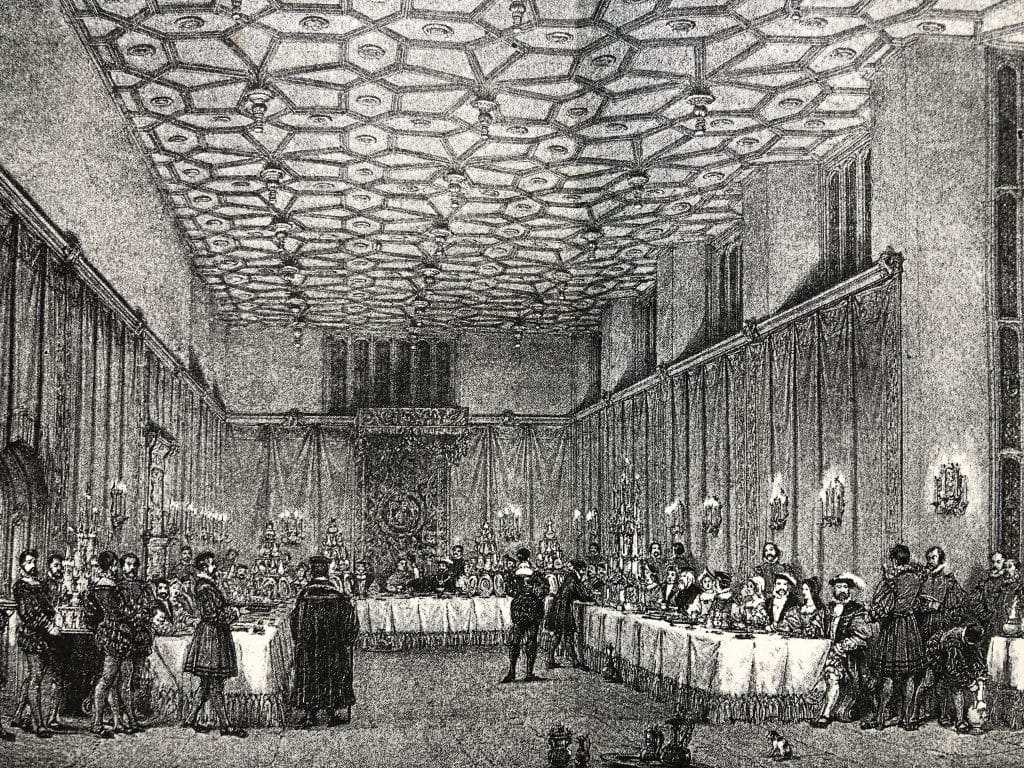

Westminster Hall is one of two surviving buildings from the medieval Palace of Westminster, which burnt to the ground in the mid-nineteenth century. It has ‘the largest medieval timber roof in Northern Europe. Measuring 20.7 by 73.2 metres (68 by 240 feet), the roof was commissioned in 1393 by Richard II, and is a masterpiece of design. It has witnessed many State occasions, is truly magnificent and will take your breath away.

Some of the critical events you will be interested in as a lover of Tudor history are the following: the scene of coronation banquets including Anne Boleyn’s in 1533; tragically, also the scene of numerous Tudor state trials including Sir Thoms More (1535), John Cardinal Fisher (1535), four of the men accused alongside Anne Boleyn in 1536 (excepting George Boleyn), the Protector Somerset (1551), 4th Duke of Norfolk (1572) and Edmund Campion and other Jesuits (1581).

Look out for the plaques on the floor commemorating these state trials and various lying-in-state events, including that commemorating the trial of Sir Thomas More and the lying-in-state of like Winston Churchill and the late Queen, Elizabeth II. Also, make sure you use the account of Anne Boleyn’s coronation in In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn to try and identify the upper window from which Henry VIII watched the coronation banquet below. Imagine Charles Brandon riding into the hall on his charger. WOW!

Visits to Westminster Hall must be booked in advance, and it is not always open to the public. So, you will need to do your research ahead of time and plan your visit carefully. Generally, the Hall is open when Parliament is NOT sitting. Therefore, it tends to be open on Saturdays, with more dates over the Parliamentary summer recess. If you are a UK resident, you can contact your MP to arrange access at any mutually convenient time for free.

When you are finished, head to Westminster pier and take a Clipper to the Tower of London. It is by far the most interesting, invigorating and pleasant way to move between these two locations. Although, of course, the Underground is also a convenient option. The nearest stop is Westminster, found on the corner of Parliament Square.

This is the second of my ‘Big Three’ Tudor locations in London. It is an austere place with a formidable and chilling reputation. Combining this with a morning visit to Westminster Abbey will undoubtedly be a packed, and quite long, day.

You will easily be able to spend half a day visiting the Tower of London. If you follow this guide and come to the Tower for the afternoon, you might be able to witness The Ceremony of the Keys, which takes place every evening, as it has done, unchanged for centuries. Admission is by pre-booked ticket only at 9.30 pm and leaves from the main entrance. It is extremely popular, and the demand for tickets is high. So, good luck!

Regardless, at the end of your day, can feel satisfied that you will have nailed two out of the three most important locations in London for Tudor history lovers to visit.

Having arrived at the Tower Pier by Clipper or Tower Hill by Tube, you might want to enjoy a bite to eat by the riverside. I can recommend eating lunch at the Coppa Club. it is right next to the Tower Pier and the river front. If you are organised and can afford it, I’d book one of the pods outside. (You need to commit to spending a minimum amount when you dine in a pod so check on that in advance and don’t be caught with a hefty bill that you weren’t expecting). They make for a special occasion and will be the icing on your cake for the day!

Right, back to the history of the Tower. Here are some highlights of the history of the Tower and notable Tudor locations associated with it:

Early History of the Tower:

1100: William I (the Conqueror) completes the Tower’s central keep.

1240: The White Tower only became known as such after it was painted white in 1240 during Henry III’s reign so that it would be visible for miles! This was a Palace-Fortress designed to impress as well as subdue a potentially rebellious population.

Tudor Times:

The Tower as Palace:

1503: Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII, died following childbirth, in 1503, on her 37th birthday. The child, a daughter named Katherine also died.

1533: In preparation for Anne Boleyn’s coronation, Henry VIII ordered new Royal apartments to be built. On 29th May 1533, Anne arrived at the Tower by the river, surrounded by a flotilla of other barges to be greeted by the King. The couple then processed to the new royal apartments where they spent time preparing for her coronation. This included Anne being presented with plate for her household from the Jewel House.

The Tower as a Treasury:

Henry VII had a jewel house built at the Tower, just in front of the White Tower, facing towards the riverside. This is where the King kept vast quantities of coin and, it is thought, the coronet placed on his head at Bosworth.

The Tower as a Prison:

Many high-ranking prisoners were kept at the Tower during the Tudor era including: Sir Thomas More, Bishop John Fisher, Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Katherine Howard and her lady-in-waiting Lady Jane Rochford, the future Elizabeth I when she was still Princess Elizabeth, Lady Jane Grey, Anne Askew, Margaret Pole and many other unfortunates.

Both More and Fisher were executed on nearby Tower Hill. Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey and Margaret Pole were all executed within the Tower and are buried at St Peter ad Vincula. The headless body of St John Fisher is buried among the corpses of hundreds of executed prisoners in the crypt of the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London, whilst his head is believed to be buried under the porch of All Hallows-by-the-Tower, the oldest church in the City of London. More’s bones are also now deposited in the crypt of the same chapel.

Anne Askew was illegally tortured at the Tower in an attempt to get her to implicate Queen Katherine Parr in heresy. She didn’t.

Lady Jane Grey came to the Tower in 1553. It was tradition for a new monarch to take possession of the Royal Palace and to prepare for their coronation. However, Mary Tudor was victorious in quickly raising support for her claim to the throne. Support for Jane fell away, and the palace turned into her prison. Lady Jane was tried at the Guildhall on 13 November 1553 and found guilty of treason. She remained a prisoner and perhaps could have been eventually pardoned. However, the Wyatt Rebellion in early 1554, persuaded Mary that as long as Jane lived, she could be a potential figurehead for Protestant uprisings.

Jane was executed at the Tower on 12th February 1554 and was buried in St Peter ad Vincula.

As a princess, Elizabeth I spent eight weeks at the Tower in 1554. While there she was interrogated regarding her involvement in the Wyatt Rebellion, which sought to depose Catholic Mary and replace her with the Protestant Elizabeth. Elizabeth kept her nerve, and no evidence could be found against her. Elizabeth was released and transferred to Woodstock Palace in Oxfordshire, where she was kept under strict house arrest.

Anne Boleyn is probably the most famous prisoner at the Tower. She was brought there following her arrest at Greenwich Palace on 2 May 1536. She disembarked at the Queen’s Stairs by the Byward Tower. She would never see the outside world again. the Queen was lodged in the Royal apartments, which had been built for her coronation in 1533.

Her trail took place in the Great Hall, part of the royal palace on 15 May. She was tried alongside her brother nad both were found guilty of treason. The five men found guilty alongside her: her brother, Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, William Brereton, Mark Smeaton were executed the following day, 16 MAy on Tower Hill. Anne died on a specially erected scaffold on the north side of the White Tower on the morning of 19 May. Having been wrapped in white linen, and placed in an arrow chest, her body was buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby Royal Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula.

If you would like to hear more about the Tower as a prison, there is a member only episode in podcast fil, which you can access via my meember-only podcast page here.

Visiting Today

The Tudors would still recognise the Tower as it is today, and we can still see the postern gate through which Anne Boleyn entered at her coronation and imprisonment. The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula is a working chapel. Regular services are open to the public (although as you will see, this does not entitle you to free access to the Tower). If you are lucky, you can access the chapel at certain times. I have found this usually involves schmoozing one of the very distinctive and usually friendly Beefeaters!

Unfortunately, the royal apartments that Anne Boleyn stayed in before her coronation in execution no longer exist. Nor does the Great Hall in which she and her brother were tried. Only the stone footings of the Cold Harbour Gate, which separated the inner (royal) ward from the outer ward survive. of course, this is the gate through which Anne Boleyn walked to her execution. However, the onion-shaped turrets on top of the White Tower, placed there in 1533 as part of the refurbishment of the Tower for Anne’s coronation can still be seen in all their resplendent glory!

- What to see and do:

- Crown Jewels

- St Peter ad Vincula

- The Medieval Royal Palace

- The White Tower to see the Chapel of St John the Evangelist and Henry VIII’s armour

- The Beauchamp Tower to see graffiti of prisoners (but look out in all of the towers)

- Do I have to pay?

- HRP Membership

- Book Online beforehand and go straight to the entrance.

Tower Hill Scaffold

Origin of Tower Hill as an Execution Site:

The first execution on Tower Hill was carried out by a mob, who beheaded Simon Sudbury, Bishop of London, on the site during the Peasants Revolt of 1381. In 1485, a permanent scaffold was erected on Tower Hill. It was used for the final time in 1747.

Tudor Times:

Many Notable Executions at Tower Hill including: Sir Thomas More and Bishop Fisher and the men caught up in the downfall of Anne Boleyn. On the 17 May, all five men were taken from the Tower to the place of execution on Tower Hill. Theirs would be a public execution, commuted from being hung, drawn and quartered to death to beheading. The men were put to deth by order of rank. This meant that George Boleyn, Lord Rochford was beheaded first followed by Sir Henry Norris, Sir Francis Weston, Sir William Brereton and finally after watching the horror unfold, poor Mark Smeaton.

What is there now:

A memorial garden was created during the reign of Queen Victoria and now sits within a larger memorial park dedicated to those who lost their lives at sea during the World Wars and who have no graves.

What to see and do:

You will find a small paved garden on the site. Some of the names of those notables who lost their lives on Tower Hill are commemorated but sadly, not all. Some of those missing are the five men mentioned above, who were ensared in the fall of Anne Boleyn. The other memorials in the garden commemorate members of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets killed during World War One and Two.

Do I have to pay?

No, it’s a free park.

How to get there:

Walk up the hill with the Tower on your right and cross over the pedestrian crossing to cross the busy road.

Day Two: Hampton Court Palace

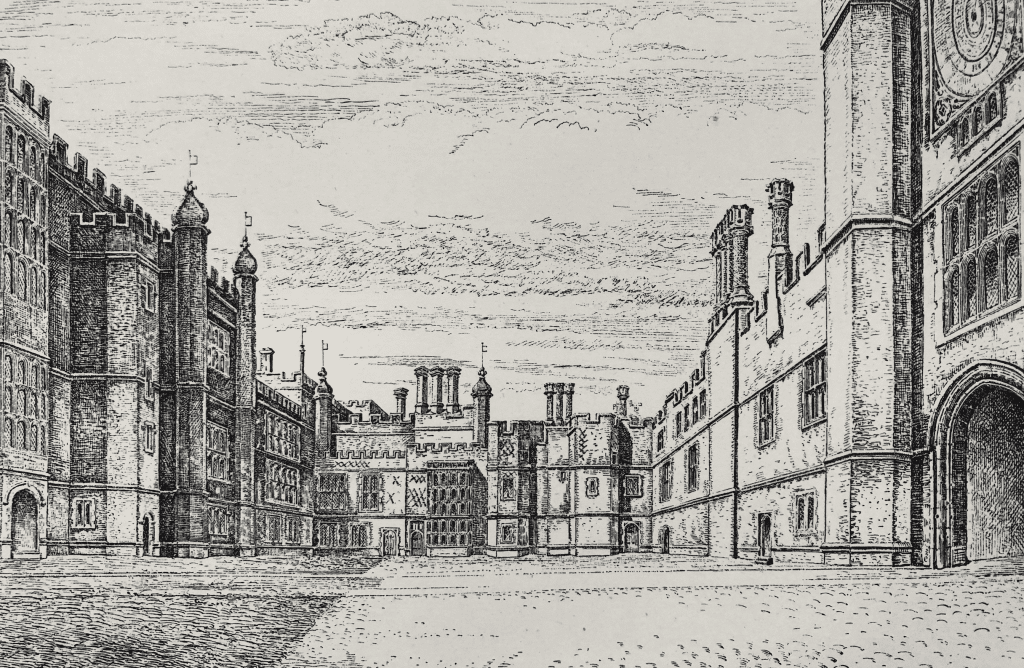

Hampton Court Palace is the third location of my ‘Big Three’ Tudor hotspots. It is a must for any first-time visitor to England as it is the only Tudor palace to survive. even then, half of the palace was demolished during the reigns of William and Mary with a Baroque palace replacing some of the Tduro ranges, notably those around Fountain Court which once contained the Queen’s Privy lodging range. Due to the death of Queen Mary and a shortage of funds, the renovation project was abandoned – thank goodness! This leaves us with a somewhat Schizophrenic building: half-Tudor – half-Baroque.

What remains is the outer Base Court, the original royal lodging range in Clock Court (although much of this has been disastrously meddled with over the centuries so that the interiors have been almost entirely lost and many of the spaces are not open to the public) the staterooms, including the Great Hall, Great Watching Chamber, Council Chamber, Haunted Gallery, chapel and kitchens.

Below, you will find a summary of the origins and Tudor history of the palace, as well as some pointers as to often overlooked /less well known features to look out for that might not be included in the usual guide books.

Hampton Court Palace is featured in more detail in my two co-authored In the Footsteps books. However, as a valued member of The Ultimate Guide, I am also including a link to my digital miniguide on Hampton Court called, A Tudor Day Out…in Hampton Court (only usually available in my shop) to compliment this text.

Hampton Court Palace Timeline:

1086: Built by Water de St Valerie

1200s: Ownership transferred to Henry de St Alban

1236: Knights Hospitaliers – land rented or sold by Henry de St Alban

1494: Giles Daubeney – Lord Chancellor to Henry VII. (You can see Giles Daubeney’s tomb in Westminster Abbey)

1514: On midsummers day, 21 June 1514, an indenture was granted from Thomas Docwra, prior of the Knight’s Hospitaller, to ‘the most Rev. Father in God Thomas Wolsey, Archbishop of York’ for the lease of Hampton Court for a term of 99 years at a rent of £50 per annum. Wolsey goes on to create a magnificent English palace with deeply Italianate influences.

He demolished the existing moated manor and built the red-bricked palace we know today – base court & inner court (Clock Court); a great hall on the ground floor, a privy lodging range (3 floors), kitchens, a magnificent gallery and began work on the chapel.

1529: Henry VIII took possession of Hampton Court. The main addition to the building was the completion of the chapel, including the carved oak ceiling, creating an additional level on top of the existing privy gallery and constructing a new courtyard on the east side of the palace. Around this courtyard, the new Queen’s Apartments were built. These were intended, initially, for occupation by Anne Boleyn, but not occupied until after Jane Seymour’s death.

1533: on 28 November, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, and illegitimate son of Henry VIII, marrys Mary Howard in the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court.

1534: The stillbirth of Anne Boleyn’s second child in the old queen’s privy lodging range (the room still exists but is not accessible to visitors).

1537: The birth of the future Edward VI in the old queen’s bed chamber (the same room mentioned above), followed just days later by the death of his mother, Jane Seymour.

1541: The arrest of Katherine Howard.

1543: Henry marries to Katherine Parr in the queen’s closet at Hampton Court Palace

1760: George III becomes king and abandons Hampton Court as a royal residence, turning it into ‘grace and favour’ apartments.

Visiting Today

Must-Sees: There is so much to see at Hampton Court. hence we have dedicated the entire day to visiting this one location. You will want to take your time to drink it all in. Perhaps even wander around the palace for a second time!

Of course, the Hampton Court Palace shop has guide books for sale. However, these necessarily have to cater for the later history of the palace, thus diluting the amount of time and space dedicated to exploring all its Tudor nooks and crannies. As Connoisseurs of Tudor history, I know you don’t want to miss a thing. Hence I have created my Your Tudor Day Out…in Hampton Court Palace digital miniguide, (which I encourage you to download) and am highlighting some of those often missed features below – that is unless you know what to look out for, of course!

Wolsey’s lost range: In Clock Court, look out for he imprint of Wolsey’s ‘lost wing’ of the palace, picked out on the ground. This is what Clock Court would have initially looked like before the wing was demolished and the later portico added that you will see today.

The Old Royal Apartments: Also in Clock Court, with your back to the astronomical clock, admire the old royal apartments stacked over three floors. These were initially intended for Princess Mary (on the ground floor), Henry VIII (the first floor) and the Queen (on the second floor). At ground floor level an archway was punched straight through the middle of Princess Mary’s lodgings during the later redevelopment of the palace. During the Tudor period, it would have formed one continuous range.

Site of Henry VIII’s Wardrobe and Stairs. Also in this range, but to the right of the central archway is a turret tower. Today, it is signposted as a buggy park and locker room. Poke your head into the doorway. You will see a flight of wooden spiral stairs of some age. The modern-day locker room was the site of the King’s Privy Wardrobe, where some of his clothes were stored, cared for and readied daily. They would then be taken up that spiral staircase, and at the top, handed to a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber. We will come to the top of those stairs momentarily to pick up the story…

In the Great Hall: Look out for the initials ‘HA’ carved into the oak screen that separates the screen’s passage (as you enter) from the main body of the hall. there are two sets, one on your right as you walk in and one of your left. You must enter the hall and turn around to examine the screen. The initials are above head height but clearly visible.

More recently a new falcon badge has been added to the exhibits on display in the great hall. This was recently rediscovered, and according to Paul FitzSimmons who discovered the badge on an auction site, work to research its origins has shown ‘an incredible likeness in both size and design to the 43 surviving falcon badges decorating the ‘frieze’ above the windows and hammer beams in the palace’s Great Hall’. This means that the badge is a likely element of the room’s original Tudor scheme.

In the Great Watching Chamber: As you pass from the Great Hall to the Great Watching Chamber, look immediately to your right. The closed doors show the remains of the entrance to the Presence Chamber. The area beyond these doors has been drastically reconfigured, and all the interiors stripped out. These spaces are not open to the public, but this doorway hints at what has been lost. It also shows how the palace’s rooms flowed from one to the other. If you want more details about this sequence, you can download my guide How to Read a Tudor House.

Henry VIII’s Privy Chamber and Bedchamber: As I have already mentioned, the rooms beyond the State apartments that once made of the King and Queen’s lodgings have been extensively remodelled over the centuries, particularly when the palace was turned over to being ‘grace and favour’ apartments and was no longer used as a royal palace. However, using old floor plans, we can make out the area once occupied by Henry VIII’s Privy Chamber and the King’s first bedchamber (Henry had another bedchamber in the Bayne Tower, which he probably used more often as it afforded greater privacy)

You will find this area of the palace inside The Cumberland Suite. As you pass int it, the first room occupied at least a part of the Privy Chamber, then a short, narrow passage leads through into another room, with three alcoves on the left hand wall as you enter. As you enter the short passageway, the first door is the head of the spiral stairs coming up from the King’s Wardrobe and the second room was once Henry VIII’s Bedchamber.

Notice a blocked-up doorway with a typical Tudor arch that once connected to Wolsey’s rooms, thus giving the Cardinal direct and private access to the King. Although you can see no trace of it now, the wall at the back of this same alcove once connected to the Bayne Tower, which contained he King’s most private rooms.

The Bayne Tower: Speaking of the Bayne Tower, set behind a wall in Fountain Court is the Bayne Tower. Its exterior can be viewed from the courtyard. Although it is a bit of a hotch-potch of architectural styles, you can nevertheless glimpse one of the most private areas of Henry VIII’s personal life. It contained his jewel-house, study, library, offices, wardrobes, bedrooms, bathrooms (with hot running water!) and drop latrines.

In the summer, this courtyard is often turned into an outdoor cafe. It is a lovely place to enjoy coffee/lunch in the summer in more civilised surrounding that the very busy, thoroughly modern, Titlyard Cafe.

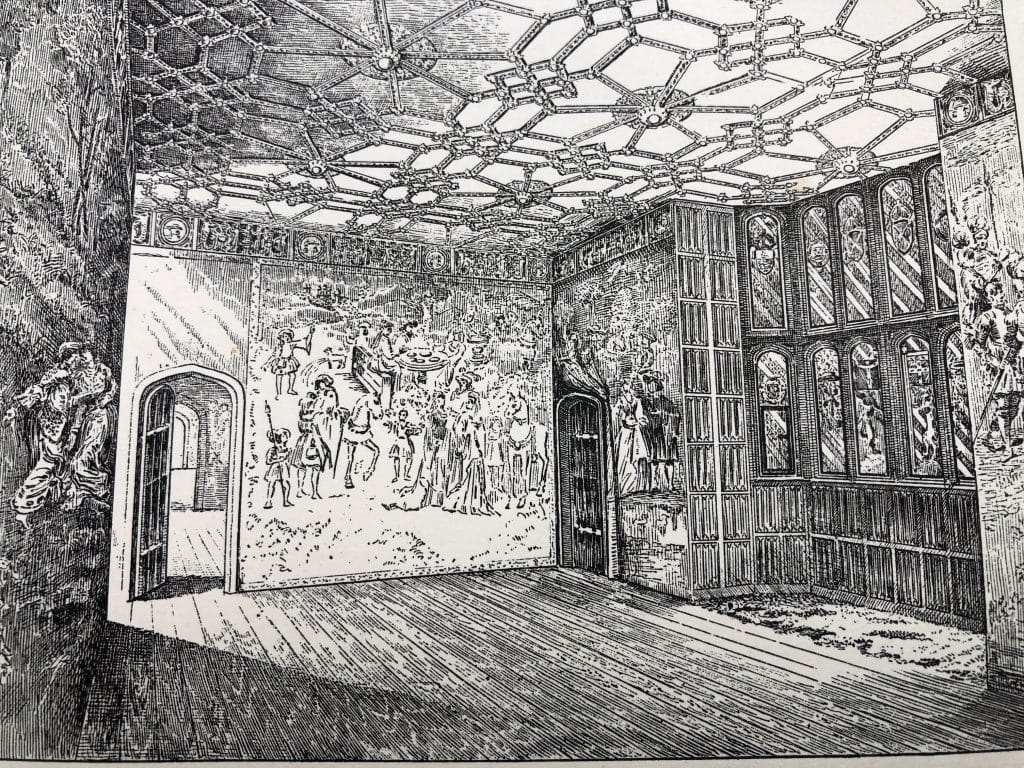

The Wolsey Rooms: The Wolsey Rooms are often used as gallery space for special exhibitions, such as the Gold and Glory exhibition of 2021. In between times, it can be closed to the public or stripped back to illustrate its use as a privy suit of rooms, once used by Wolsey. Notice how the chambers get smaller and smaller, typical as we move from more public to intensely private closets. The panelling is original, and you will see a blocked-up doorway in the last room. This once led into the King’s privy gallery. It is a building I would have loved to have seen but sadly was demolished when the new Baroque Palace was built.

The Real Tennis Court. Built in 1528, the real tennis court at Hampton Court is the oldest in England. You need to head out the back of the palace and into the garden to access it. Wonderfully, the court continues as a working real tennis club. However, opening to the public seems patchy. So, best to check ahead of time to see if it will be open. Details of the royal tennis court can be found here.

The Stables: About 100 m down Hampton Court Road are the original stables used to house the King’s horses. Incredibly it survives and is STILL used as a stable today. It is not open to the public as far as I know but you can admire it from the outside.

Tours:

You might not be aware that Hampton Court Palace has several special tours. These allow you to see the palace from different angles…These include tours on ‘Art and Architecture’, ‘Life at the Palace’, ‘Roof top’ tours and Ghost tours.

Prices vary from £130 to £300, depending on the tour.

Check out further details and prices here:

Do I have to pay?

Members: Free (HRP membership: worth it if you visit an HRP property on three occasions in a year if you are single). If you are going to visit two or more HRP properties as a couple, then it is worth buying this in advance.

NB: Quote from HRP website: ‘If you have purchased a membership but live overseas, we will post your membership card to you, but delivery may take longer than the standard 28 days.’

Travel From Westminster

River Cruise:

From Westminster Pier at the base of Big Ben, travellers can take scheduled river cruises with a choice of operators to Hampton Court. The 22-mile journey, depending on the tide, can take as little as 2 1/2 hours up to four hours – an average time of 3 hours.

At the Kingston Bridge, a short 25-minute river cruise takes passengers from Kingston to Hampton Court, departing at 10:45 a.m (always check the relevant website for the latest details).

For additional reading about the early origins of Hampton Court, you might want to check out my blog: Hampton Court: The Emergence of a Tudor Palace.

Day Three: Greenwich and Eltham Palace:

Sadly, nothing remains above ground of what was once one of the greatest and most beloved palaces of Tudor England. Greenwich Palace suffered terribly during the English Civil War and with no monarchy to invest in its maintenance, it quickly feel into decay. It was finally torn down in the latter half of the seventeenth century.

However, Greenwich Village and its adjacent park, once part of the palace’s royal hunting park, is a charming spot. And with so many significant Tudor events having taken place at the palace, including the birth of three Tudor monarchs, it is worth a visit.

Origins of Greenwich Palace:

In Anglo-Saxon times, the land at Greenwich was gifted to the Abbey of Ghent, in Belgium. In 1414, Henry V disallowed possession of all land by foreign monasteries, so Greenwich came into the possession of the Crown.

In the fourteenth century, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, uncle of Henry VI, built a house on this land, which abutted the southern bank of the River Thames. It was called Bellacourt. The Duke fenced off 200 acres of land around his house to form a park, much of which is now Greenwich Park, as well as building a tower on the pinnacle of the hill overlooking the palace. This became known as ‘Duke Humphrey’s Tower’. During the sixteenth century, it is said that Henry VIII kept some of his fine wine and mistresses in the Tower! It certainly would be a convenient place for his extra-marital assignations. Today, the Royal Observatory stand in its place.

When Humphrey died in 1447, Bellacourt passed to Henry VI’s wife, Margaret of Anjou.

Tudor Times:

Of course, Henry VII inherited the house when he was victorious at the Battle of Bosworth. He rebuilt much of the Palace at the turn of the sixteenth century when it became known as the Palace of Greenwich. From this point, Greenwich served as the principal royal palace until the building of Whitehall Palace in the reign of his son, Henry VIII.

Of course, Henry VIII was born at Greenwich in 1491 and, when he inherited the throne in 1509, continued his father’s aggrandizement of the building, redesigning the chapel and constructing a tiltyard with viewing towers for his favourite sport, the joust.

Events:

As mentioned above, several momentous events occurred at Greenwich Palace. The most important Tudr events are summarised below:

Henry VIII was not the only monarch to be born at the Palace. His daughters, the Princesses Mary and Elizabeth were born at Greenwich in 1516 and 1533, respectively .

Greenwich also saw the marriage of Henry to his first and fourth wives: Katherine of Aragon and Anne of Cleves. Katherine’s wedding to the King took place in the Church of Observant Friars, situated next to the Palace, while Henry and Anne were wed in the Queen’s Closet.

At Christmas 1529, Henry and Anne Boleyn spent the festive season at Greenwich designing their new palace, which would eventually become known as Whitehall. Sadly for Anne, Greenwich Palace was also the scene of her arrest on 2 May 1536.

In 1553, Edward VI, whose health was failing, moved to Greenwich hoping that the country air would help. It didn’t, and he died at the Palace in terrible agony on 6 July 1553.

By the reign of Elizabeth I, Whitehall Palace was firmly established as the principal London residence of the monarch. However, the Queen liked to spend summers at Greenwich alongside her favourite, Robert Dudley. He had swanky riverside apartments with his bedroom sporting a rooftop balcony, where he apparently enjoyed taking his supper.

Decline:

The first Stuart King of England, James I, gave the palace to his queen, Anne of Denmark. She is responsible for constructing the Queen’s House, which now houses an art collection, including the Armada Portrait.

By the time of the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the palace was dilapidated. Plans were made to rebuild a modern palace, but money ran out when only one wing had been completed. In the 1670s the Tudor Palace was utterly demolished. However, I understand that The Royal Observatory uses Tudor Brick from the Palace!

In 1694, Queen Mary II decided that Greenwich should be the site of a new hospital for seamen. It then became the Royal Naval College, now known as the ‘Old Royal Naval College’ but today in use as a music college.

Visiting Today

Must-Sees:

- The stone plaque which commemorates the births of Henry VIII, Mary I and Elizabeth I near the riverside.

- The Armada Portrait in the Queen’s house, plus other Tudor portraits.

- In the visitor centre, peruse the Tudor finds, which surfaced during an archaeological dig, plus and model of Greenwich Palace.

- In the Painted Hall, some of the palace’s foundations can be seen beneath the floor. According to the Royal Museums of Greenwich website, ‘Archeological work in 2017 revealed some remains of Greenwich Palace beneath the Old Royal Naval College. Two service rooms connected to the palace’s Friary buildings were discovered; the foundations can still be seen beneath the floor of the Painted Hall. One of the rooms includes odd niches in the walls, thought by archaeologists to have once been used as ‘bee boles’ – places to keep bee hives during the winter.’

Do I have to pay?

Many of the museums at Greenwich are free, but you have to pay to visit the Painted Hall, the Royal Observatory and the Cutty Sark.

Where to eat and drink: Greenwich is an affluent part of London, has a village feel and is well-served by restaurants, pubs and coffee shops. You will find familiar chains and independent establishments. There are also cafes available at the Visitor Centre and the Maritime Museum.

How to get there:

- River: Thames Clipper to Greenwich Pier – by far the best way!

- Tube: DLR line to Cutty Sark for Maritime Greenwich, which is in Zone 2 (take trains for Lewisham).

- Overground train: Trains to Greenwich Station, a 10-minute walk to Greenwich Visitor Centre.

Having enjoyed a morning at Greenwich, head on over to Eltham Palace. Getting to Eltham is not as easy as many of the locations features. My preference would be to pick up a taxi in Greenwich to take you over to Eltham and then arrange a time to be collected to take you back to Greenwich. For completeness, I have included the transport options for getting to the palace below. If you want to listen to my podcast recorded on site with Jeremy Ashbee from English Heritage, click here.

In the meantime, let’s going going with a potted history of the site.

Origins of the Palace:

1086: Eltham was first mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 as being in the possession of William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Bishop Odo, Bishop of Bayeux.

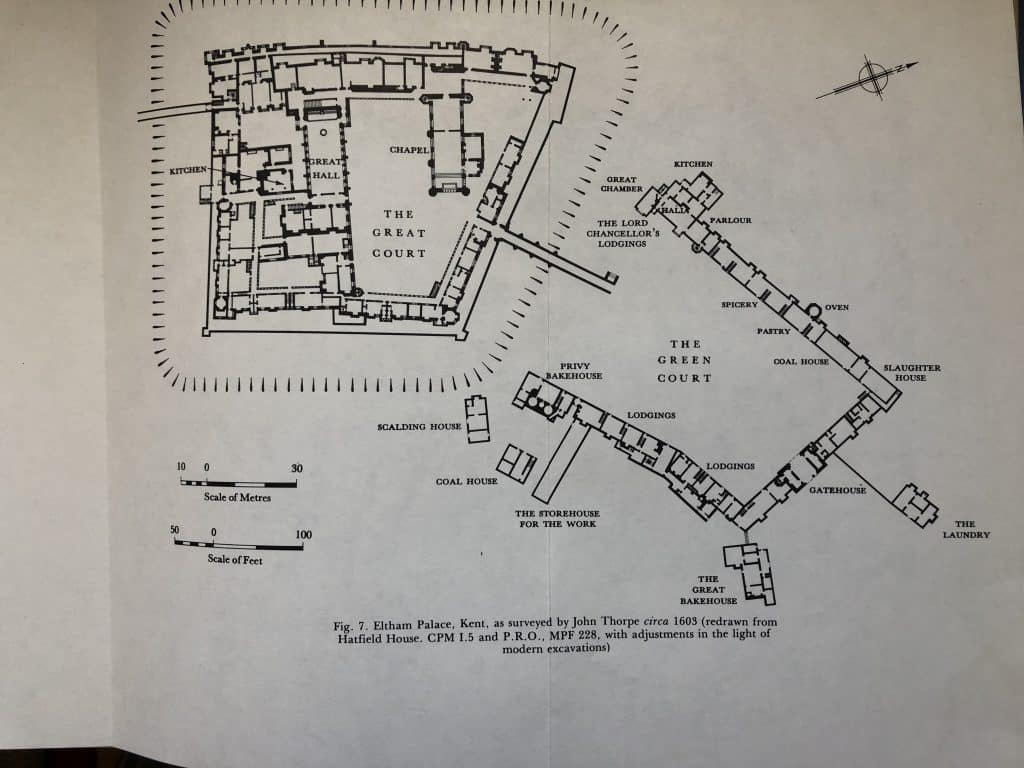

1295: Bishop Bek built extensively here including a defensive wall within the moat. He gifted Eltham to the future Edward II when the latter was Prince of Wales. Eltham Palace then remained in the possession of the Crown, and by the early 1300s was among the country’s largest and most often used royal places in England.

1482: Edward IV favoured Eltham and completed further building work, including the Great Hall which still survives today. At Christmastime in 1482, Edward IV and his Queen,Elizabeth Woodville, held a feast at Eltham Palace for 2000 people!

Tudor Times:

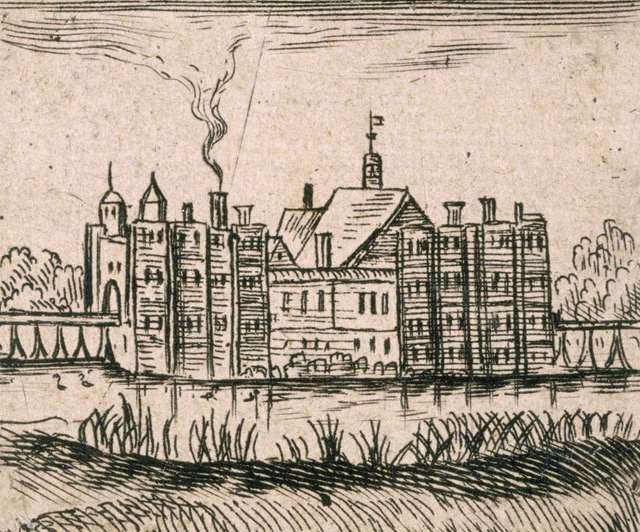

Alongside us are the footings of the King’s lodgings with the Great Hall in the background.

During the reign of Henry VII, Eltham served as the Royal Nursery where the future Henry VIII, his sisters Margaret and Mary and younger brother, Edmund, were educated under the watchful eye of their mother, Elizabeth of York.

1499: The Dutch Philosopher, Erasmus, visited Eltham to see his friend, Sir Thomas More. During that visit, the 9-year-old Prince Henry (later Henry VIII) challenged Erasmus to write a poem, which the scholar duly did. He returned 3 days later with a poem in praise of Henry VII and the Princes Arthur and Henry.

1509: By the reign of Henry VIII, Eltham was one of only six royal residences large enough to accommodate the whole court of around 1000 people.

1515: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey took the oath of office as Lord Chancellor at Eltham on Christmas Eve 1515

1517: Henry VIII had a tiltyard created to the East of the Palace, and in the 1520s he made extensive alterations and additions at Eltham. In addition to constructing a new range of lodging for the King and a new brick-built chapel, alterations were also made to the Queen’s apartments.

This work left little by way of gardens in the Palace, so new gardens were constructed to the South and West. Henry VIII accessed these gardens by way of a wooden ‘Privy Bridge’, which can still be seen today, although the timber bridge was replaced in the twentieth century.

Despite Henry’s clear early favour toward Eltham Palace, it was used less and less as the reign progressed and his new Palaces of Whitehall and Hampton Court took pre-eminence. Henry VIII was the last monarch to spend significant time at Eltham.

Decline:

Elizabeth I and her successor James I, spent money renovating the Palace. Despite this, it was only occasionally used by the court and fell into decline. Charles I was the last monarch to visit,, but by that time, Eltham was past its glory days, and there were reports that parts of the Palace were collapsing.

1640s: A period of occupation by Parliamentary Troops during the English Civil Wars of the seventeeth century sealed the palace’s fate. Charles II showed little interest following his restoration to the English throne, and it was leased to a friend who also chose not to live there.

By the eighteenth century, the whole site was used for agricultural purposes, and Edward IV’s Great Hall had been converted into a barn!

Revival and Survival

1933: In 1933, a wealthy American couple, the Courtaulds, were looking for a country estate within reach of London. They found Eltham, bought a 99 year lease for the site, and employed architects to build them a modern mansion while maintaining as much of the old palace as possible.

Although their plans to construct a home in the height of Art Deco fashion, directly adjacent to the medieval Great Hall, were controversial, without their money and care, perhaps nothing of Eltham Palace would have survived.

Today, like Hampton Court, Eltham Palace is a tale of two buildings: half Art Deco and half Medieval / Tudor. As a Tudor lover, the Art Deco part of the house may not be your thing, but it is interesting and elegant in its way, and is considered one of the finest examples of an Art Deco house in the country.

Visiting Today

Must-Sees:

- The original medieval bridge crossing the moat at the entrance to the Palace.

- Edward IV’s Great Hall. Notice the Yorkist ‘Sun-in-Splendour’ emblem over the external entrance to the hall.

- The footings of the King and Queen’s Privy Lodgings facing west, with London’s skyline in the distance.

- The Moat – as well as being a pleasant walk, when you’re in the moat you can see the earliest part of the defensive wall, the Privy Bridge and the original Elizabethan sewers that once empited into the moat.

Do I have to pay?

English Heritage members go free. Overseas vistor passed are available via English Heritage, alllowing you to get a temporary pass for a set number of days. You do not need to book in advance but the prices may be more on the door.

Where to eat and drink: A cafe on site and there are picnic tables if you wish to take your own bite to eat.

How to get there:

Eltham is a little out of the way, although not too far from Greenwich. However, getting there is not as straight forward with some of th eother locations featured in this itinerary. I would recommend grabbing a taxi in Greenwich village and making sure you arrange with the taxi firm to pick you up again at a specificed time, outside the entrance to the Palace. Do check the likely fare before getting into the taxi. However, there are other options:

Overground train to Mottingham Station. The station is half a mile from the Palace and takes approximately 10 minutes to walk between the two.

Car: There is ample parking which is chargeable, unless you are an English Heritage Member. Use postcode SE9 5NP in a sat nav.

Bus: Routes 124, 126, 160 or 161 stop a short distance from the Palace. (Jounrey time approximately 50 mins)

If you wish to read more about Eltham Palace’s role as a royal nursery, you can check out my blog Eltham Palace: London’s Royal Nursery

Day Four: The Charterhouse, The Museum of St John, St Bartholomew the Great and Sutton House

On day four, we head into the City of London to Smithfield and Clerkenwell to visit three monastic Tudor sites before exploring a little further afield and visiting an early Tudor courtier’s house that has survived the passage of time remarkably well.

The Charterhousewas once one of THE most prestigious monastic institutions in England. Sons of learned and wealthy families vied to secure a coveted position at the monastery. If you want to read a detailed write-up of the monastery and its history, check out my blog: The Charterhouse: Power, Piety, Treason in the City. You can also listen to my podcast recorded at the Charterhouse here. In the meantime, I will summarise its history and provide information to help you plan your visit.

Origins of The Charterhouse:

The Charterhouse was completed around 1420, thanks to the generous patronage of wealthy aristocrats. However, the monastery did not reach its zenith until the first 30 years of the sixteenth century under Prior William Tynbygh.

Tudor Times:

During the early Tudor period, before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Charterhouse was one of only nine Carthusian Monasteries in England – and as I have already mentioned, was by far the most prestigious.

1534: When Henry VIII moved to divorce Katherine of Aragon, thus breaking with the Holy Roman Church in Rome, a bloody struggle broke out between the Crown & the holy men of the Charterhouse. It’s Prior, John Houghton, and the procurator refused to sign the 1534 Act of Succession and both were briefly thrown into the Tower.

1535: In 1535, when it became mandatory to sign the king’s Act of Supremacy, making Henry VIII Head of the Church in England, Houghton and several others refused to bend to the king’s will. Many of the brethren suffered terribly for their intransigence. Prior John Houghton was hung, drawn and quartered. Others were tied by chains to posts, hands behind their backs, and left to starve to death in Newgate prison. Some monks who remained behind at the Charterhouse understandably capitulated to Henry’s wishes.

1536-38: The following year the last prior, William Trafford, was appointed, but he finally surrendered the Charterhouse to the king on 10 June 1537. However, the priory did not finally close until 15 November 1538, when the remaining monks were evicted.

Sir Edward North (creature of Sir Richard Rich) and Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations acquired the property and built himself a new home on the site of the Charterhouse: it was renamed ‘North House’.

1558: Between 23-29 November, 1558, Elizabeth I kept her court at the Charterhouse. She was on her way from Hatfield House to make her entry into the City, having been proclaimed Queen following her half-sister’s death on 17 November.

1561: From 10-13 July, Elizabeth revisits the Charterhouse as a guest of Lord North.

1564: After Lord North’s death on 31 December 1564, North House was purchased by Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk. The Duke had been looking for a new London base. North House was both conveniently situated close to the court, away from the dankness of the river (unlike Lambeth House, which had been the Duke’s main residence in London until this point) and en route to the Duke’s principal country home at the time, Kenninghall in Norfolk.

1571: Unfortunately, the ambitious and deeply conservative Duke of Norfolk fell foul of accusations of treason due to plotting to marry the Catholic Queen, Mary Stuart. The Duke’s advisor, Lawrence Bannister later recalled a conversation in the gardens of Howard House in May 1569. As a result, Norfolk was arrested and thrown into the Tower but allowed out, only to be placed under house arrest at Howard House. Unable to keep out of trouble, the Duke soon became involved in the Ridolfi plot to overthrow Elizabeth and put himself on the throne alongside Mary, Queen of Scots. The aim was to restore Catholicism to England. This plot was uncovered on 6 September 1571. Norfolk was arrested on charges of treason and executed on Tower Hill on 2 June 1572

Decline:

Sadly, much of the priory church has gone, and only fragments of the original monastery remain. However, a good deal is left of North House and Norfolk House.

Visiting Today

What to see and do:

Why go: It’s off the usual tourist trail, so it is quieter! It is the site of the preeminent Carthusian monastery in England & the place of house arrest of the 4th Duke of Norfolk. Elements of the surviving house show the nature of a London townhouse of the aristocratic classes.

Must-Sees:

- Norfolk’s ceiling in the Great Chamber contains thistles, possibly relating to his aspiration to marry the Scots Queen.

- Norfolk’s cloister and the blocked-up doorway to an original monastic cell.

- The Tudor Great Hall, which is used today as the brothers’ dining hall.

- The remains of the Chapter House, which are now incorporated into parts of the Charterhouse chapel.

- No10 Charterhouse Square – This building is on the site of what was formerly the residence of Lord and Lady Latimer (Katherine Parr) before Katherine became Henry VIII’s wife. My hero, John Leland, Tudor Antiquary, lived next door!

Do I have to pay?

Today, the Charterhouse functions as a working almshouse. However, it is also a museum that preserves the 600 year history of the building. You can wander around or book a guided tour. There are tours of the building, the Brother’s Tour, House and Garden Tour and the new historic interiors tour. Check out the Chaterhouse’s Tour page to find out all the latest.

Where to eat and drink:

There is no cafe on site, but the surrounding area has many restaurants and bars within easy walking distance. You might want to take a break at one of these cafes between this and our next venue: St Bartholomew the Great.

How to get there:

Barbican or Farringdon Tube (including the brand new Elizabeth line)

Church of St Bartholomew the Great

In 2023, The Church of St Bartholomew the Great celebrates its 900-year anniversary. This makes it one of the oldest churches in London having survived the Great Fire, which destroyed so much of medieval and Tudor london in 1666. Aside from the Chapel of St John at the Tower, some of the finest Norman and medieval architecture that can be seen anywhere in the capital is on display here. You may also find the interior vaguely familiar, as it has been the setting for many famous Hollywood blockbusters, including Elizabeth: The Golden Age and Four Weddings and a Funeral.

However, one of the best things about St Bartholomew is that it is well off the usual tourist trail, and you may enjoy its sublime tranquillity alone!

Origins of St Bartholomew the Great:

1123: St Bartholomew was founded in this year by Prior Rahere, Henry II’s minstrel turned holy man, whose ancient tomb can be seen near the high altar. The church was once a priory, part of a much larger Augustinian foundation.

The Priory stood adjacent to Smithfield. This was literally an open field which, even by the sixteenth century had a grisly reputation as a place of execution: William Wallace had suffered death by being hung, drawn and quartered at Smithfield on 23 August 1305.

Tudor Times:

By the sixteenth century, Smithfield became infamous as a place for burning heretics. Anne Askew, the young woman illegally tortured at the Tower in an attempt to get her to implicate the then Queen, Katherine Parr, in heresy, died in the flames at Smithfield. The woodcut that depicts this event shows the pyre directly in front of the Priory Church.

Pre-Dissolution: Before the priory was dissolved in 1539, its Prior, Prior Bolton, was responsible for managing the building of the mausoleum of Margaret Beaufort in Westminster Abbey. He also oversaw the refurbishment at Newhall, Essex, after Henry VIII purchased it from Thomas Boleyn in 1517.

Post Dissolution: Following the Dissolution of the Priory, Sir Richard Rich, who had been appointed the first Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations had the pick of those monastic properties that had become available. He chose St Bartholomew as his new London home, alongside Leez Priory in Essex, which became his principal country residence.

Decline:

Today, only parts of the original priory building remain. The nave was lost, and at least half of the north and south transepts were demolished by Richard Rich. Thankfully, the glorious choir remains alongside the near parts of the transepts, & one side of the cloisters.

The lady chapel (built in the 12th century, rebuilt in the 14th) also survives.

The architecture of the choir is stunning. Look out for Prior Bolton’s window, half way up the nave on the right. This was constructed in the sixteenth century.

Most of the priory buildings lay south of the church (the same side as the remaining cloisters), including the Prior’s Lodging, which Sir Richard Rich turned into a fabulous townhouse. Sadly, this building and other priory buildings have been lost.

However, various doorways on the south side of the church would once have connected the main body of the church to the domestic and administrative chambers associated with the monastery. This includes ‘Prior Bolton’s Door’ to be found tucked away on the south side of the church, near the apse surrounding the high altar; this door once connected the body of the church to the Prior’s Lodgings.

Visiting Today

Must-Sees:

- The Tudor gatehouse

- The Norman architecture

- The remains of the cloisters

- Prior Bolton’s window and doorway

Do I have to pay? There is no entrance fee, but a donation for upkeep is requested. One-hour tours run on Weds and Fridays. They also sometimes have events and concerts – atmospheric! Check out the website for all the latest information.

Where to eat and drink: Cafes and Bars in the surrounding area.

How to get there: Barbican or Farringdon tube.

St John’s Priory (The Museum of St John)

A short distance away from Smithfield is the parish of Clerkenwell. Once again, this little museum is off the well-worn tourist trail. To complement this entry, you can read more about the Priory via my blog: The Priory of St John: Power, Influence and Prestige in Tudor London or listen to my podcast about the Priory here. If you are a member at the Road Trip Traveller level, you can also read about the Priory in relation to Henry VII’s Northern Progress of 1486 here.

Origins of the Priory of St John:

1099: The Order of St John was founded in Jerusalem almost 1000 years ago by a sect of Benedictine monks. They established a hospital to care for pilgrims of all faiths who had made the long journey to the Holy City. The Order was renowned as being rich with powerful European connections. This made forging a relationship with the Priory of St John particularly attractive to the English Crown. During the medieval period, the Order undertook financial and diplomatic business overseas on behalf of the monarch. In return, the King extended prestigious royal patronage to the Priory.

1144: Jordan de Briset and his wife Muriel, Lord and Lady of Clerkenwell Manor, granted ten acres of land to the Order to establish a new priory in Clerkenwell.

1485: On 30 March 1485, just a couple of weeks following the death of his wife, Anne Neville, Richard III visited the priory. In the Great Hall, he addressed the Mayor, Aldermen and others gathered there and denied in a ‘loud and distinct voice’ he had never intended to marry Elizabeth of York.

Tudor Times:

1485: Henry VII required a papal dispensation to marry Elizabeth of York. The Priory of St John’s Priory, John Weston, was one of eight men selected to testify to Henry and Elizabeth’s blood relationship.

1486: The complex’s size, the Order’s wealth, and the luxurious and palatial lodgings made it an influential ally and an oft’ used residence for the royal family and distinguished foreign visitors. Retaining the close links to the Crown, Henry VII visited the Priory in March 1486, setting off on his first Northern progress from here on 14 March of that year.

Decline:

1540: The Priory was dissolved despite its good standing with the Crown.

Today, almost all of the Priory has been lost. The Tudor gatehouse called St John’s Gate (which was the Priory’s original inner gatehouse) remains, as does the twelfth century crypt of the original Priory church.

Visiting Today

Must-Sees:

- Walking down St John’s Lane, you are in what was once the Priory’s outer precinct.

- Look out for the unusually small door just inside St John’s Gate. Believe it or not, this has been reduced in height because the pavement level has increased over the centuries!

- The Normal crypt (by tour only).

- Find the Charter granting the Priory back to its brethren following the re-Catholicism of England following the death of Edward VI and the accession of Mary I (Note the beautiful image of Mary and Philip in miniature as part of the document). This document is displayed in a glass case in the museum’s Great Hall on the first floor.

Do I have to pay?

- Entry is free to the small ground-floor museum. You can donate if you wish.

- Access to the historic rooms in St John’s Gate and the crypt is by guided tours only.

Where to eat and drink: Cafes and bars in the vicinity.

How to get there: The museum is five minutes from Farringdon Tube. As you walk between the two, see what street names you can notice that give away the historical connection of this area to the Priory!

Sutton House is a time traveller’s delight! It is such an unexpected find, tucked away in an entirely tourist-free zone of London. You will feel honoured to visit and grateful it has survived. For although there have been alterations to the house over the centuries, at its core, Sutton House is a fabulous (and I would say unique) example of an early sixteenth century Tudor courtier’s house.

Ralph Sadler was responsible for building the house. He was a protégé of Thomas Cromwell. Indeed, he was raised as a boy in Thomas’ household. However, Ralph would go on to live an utterly fascinating life that spanned the reign of four Tudor monarchs. There would be intrigue and scandal in both his private and public life. His accounts as Ambassador to Scotland at the time of Mary, Queen of Scots’ birth, and his ongoing involvement with the Scots Queen until her execution in 1587 make him an invaluable witness to seismic events in Tudor history…And it all started at Sutton House in Hackney.

If you wish to read a more fulsome account of Sutton House, you can click to read my blog: Sutton House & Tudor Hackney: Ralph Sadler’s Nouveau-Riche ‘Bryck Place’. However, in the meantime, here are some highlights of the history of the house and owner. You can also listen to my on-location podcast, recorded at Sutton House here.

Ralph Sadler’s Timeline:

1507: Ralph Sadler was born in Hackney, a rural village north of London.

Circa 1514: Ralph is placed in Thomas Cromwell’s household and given an excellent education.

1535: The year before his appointment as one of Henry VIII’s Gentlemen of the Privy Chamber, Ralph Sadler began building a stylish new house in the village of his birth. it was called ‘Bryck Palce’. Today, it is known as Sutton House.

1536: Appointed as a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber, probably thanks to Cromwell’s influence.

1540: Made joint Principal Secretary to Henry VIII.

1540/1541: Ralph survives the downfall and execution of his master, Thomas Cromwell, but not before he had spent a brief spell in the Tower.

1553: Sadler signs the device for the succession of Lady Jane Grey and was placed under house arrest. However, by this time, he had sold Sutton House and was no longer living there.

1541: Sadler plays a leading role in examining Katherine Howard and her relatives in November 1541, following accusations of adultery made against the Queen.

1584: Towards the end of his life, Ralph Sadler was the gaoler of Mary, Queen of Scots at Tutbury Castle and Wingfield Manor in Derbyshire. One of his last acts was to sit at Mary’s trial.

1587: Ralph dies six weeks after Mary’s execution on 30 March. It is said that at the time of his death, ralph was the wealthiest commoner in England.

Decline:

Although parts of Sutton House have been lost (for example, there is a Georgian exterior now) and some interiors have been altered, there remains a substantial footprint of the original house. Tudor interiors from the most significant rooms in the house, such as the Great Chamber and Ralph Sadler’s study, remain intact.

Visiting Today

Why go:

- A vanishingly rare example of an early Tudor courtier’s house.

- The wonderfully preserved Tudor interiors of three rooms give the feel that you might see Ralph or his wife, Ellen, appear at any moment.

- It is well away from the usual tourist trail.

Must-Sees:

- See if you can notice the original Tudor sprung floor in the Great Chamber, put in with the house to accommodate dancing.

- Imagine Ralph entertaining Cromwell and possibly Henry VIII in the Great Chamber.

- Find the only surviving Tudor window. This can be seen clearly from the courtyard.

- Uncover a Tudor dog’s paw print on a tile displayed in the cellar. This was used as inspiration for one scene in Hilary Mantel’s book, Wolf Hall.

Do I have to pay?

Sutton House is run by the National Trust. There is a modest entry fee, and National Trust Members go free. Self-guided and guided visits are available. Check out this link for all the latest opening times and booking tickets.

Where to eat and drink: There is a small cafe on site.

How to get there: Many bus routes that stop very close to Sutton House; Tube: Hackney central station (5 minutes walk); parking is limited and payable by meter on adjacent streets.

Day Five: Lambeth Palace, The Garden Museum, and The Globe.

Lambeth Palace

Since circa 1200AD, Lambeth Palace has been the official London residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury. It is situated on the south bank of the River Thames, a little upstream but opposite Westminster and the Houses of Parliament.

Once prominent against on the skyline of the south bank of the Thames, the charming red-bricked gatehouse, which is the main entrance to Lambeth Palace, seems today to cling on for dear life against the encroachment of modern London.

Tudor Times:

During the sixteenth century, Lambeth was a convenient location for the Archbishops of Canterbury to easily reach nearby Westminster, the secular and religious heart of the capital. Whitehall Palace was also nearby.

Lambeth sat adjacent to St Mary’s Parish Church and Norfolk House, all on the south bank of the River Thames. The latter was initially the London home of the Dukes of Norfolk – and one of the places where Katherine Howard would later be accused of various indiscretions, alongside another one of her childhood homes: Chesworth House in Surrey.

Decline:

Parts of the original palace survive, including the gatehouse, Lollard’s Tower, crypt and Cranmer’s study. However, bombing during WWII destroyed the chapel and the Great Hall (first destroyed during the civil war, when the hall was dismantled brick-by-brick). Both were severely affected and were subsequently rebuilt.

Visiting Today

Why go:

- Home of the Archbishops of Canterbury from medieval times.

- Scene of imprisonment of Tudor heretics (the Lollard’s tower); Robert Devereaux, Earl of Essex, was also held in the Lollard’s Tower while being taken en route to the Tower of London.

Do I have to pay?

Access is by guided tours only. You can also email tours@lambethpalace.org.uk. Tours take in the thirteenth century chapel and crypt, the elegant State Drawing Room and Dining Room, and the magnificent Guard Room with its fourteenth century arch-braced roof. Although Thomas Cranmer’s private study survives and is still used by the incumbent Archbishop of Canterbury, it is not included in the tour, nor is the Lollards Tower.

The Palace will be closed from September 2023. As such, no tours will be held during this time. Tours will recommence from Spring 2024.

Where to eat and drink:

Next door at St Mary’s Garden Museum. There is a small cafe inside serving tea, cakes and limited meals.

How to get there:

Lambeth Palace is on the South Bank of the River Thames, between Westminster Bridge and Lambeth Bridge. it is an easy walk from Westminster.

Buses run from Waterloo, Victoria and Vauxhall stations. They stop just outside the Palace at the Lambeth Palace bus stop.

Origin of St Mary’s:

1062: Initally, a wooden church was built on the site. Later in the century, it was rebuilt in stone.

Tudor Times:

As mentioned above, St Mary’s Church and Lambeth Palace stood directly opposite Howard House in the sixteenth century. The church was used by the Howards and several members of the family, including Elizabeth Boleyn, Anne Boleyn’s mother, are buried in the crypt. Incredibly, Elizabeth’s broken tomb ledger was rediscovered quite recently (2015) during renovation work at the church. If you want to read a complete account of this exciting discovery, check out a blog by Natalie Gruneninger here.

Later History:

1647: Wenceslaus Hollar is thought to have stood on top of the tower of St Mary’s-at-Lambeth to draw his 1647 ‘Prospect of London and Westminster.’ I love him for this!

1854: The churchyard is closed to new burials; there are estimated to be over 26,000 burials on the church grounds.

Decline:

The 1970s: The church was ready for demolition. Thankfully, it was saved and converted into a garden museum.

Visiting Today

Why go:

St Mary’s is the burial place of several members of the Howard family, including:

1535: Katherine Howard, who died on 23 April 1535. She was the wife of Elizabeth Boleyn’s half-brother.

1538: Elizabeth Boleyn, Anne Boleyn’s mother

1558: Elizabeth Howard, the eldest daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, and Eleanor Percy. Elizabeth became Elizabeth Boleyn’s sister-in-law through her marriage to Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk.

Must-Sees.

The ‘lost’ tomb ledger of Elizabeth Boleyn has now been resited in the gift shop area of the church and reads: Here lyeth the Lady Elizabeth Howard, sometime Countess of Wiltshire’.

Do I have to pay?

There is an admission cost. You can either pay to simply climb the church’s tower and see the view Wenceslaus Hollar enjoyed or pay to access both the tower and the church. Check out all the latest details here.

Where to eat and drink:

There is a cafe in the church museum.

How to get there:

Lambeth Palace is on the South Bank of the River Thames, between Westminster Bridge and Lambeth Bridge. (walk from Westminster).

Buses run from Waterloo, Victoria and Vauxhall stations. They stop just outside the Palace at the Lambeth Palace bus stop.

Origin:

The Globe Theatre was opened in 1997, only a short distance from the site of William Shakespeare’s original theatre. It was the brainchild of the film director, Sam Wanamaker. It was built using building plans, methods and materials that were as close to the original as possible and just like the Tudor theatre, it incorporates an open roof with standing room for 700 people.

Interestingly, it is the only thatched building in London. All thatched roofs were banned in London after the Great Fire of 1666, and so it had to get special planning permission for the roof to be constructed from straw.

Tudor Times:

In Tudor London, Southwark was the theatre and entertainment district, away from the strict jurisdiction of the City of London. It was also famous for its bear pits and brothels.

1599: The first Globe Theatre was opened by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men; Shakespeare was part-owner of this group. He wrote the first play performed at the Globe in the spring of that year: Julius Caesar.

1613: During a performance of Shakespeare’s ‘Henry VIII’ in 1613, a prop canon misfired and caused the thatched roof to catch alight. It took two hours for the entire theatre to burn down.

1614: The Globe theatre was rebuilt.

1616: Shakespeares dies.

1642: The Puritan government of the day closed all theatres in England by Parliamentary decree. This included the Globe.

Decline:

1644: The theatre was demolished to make way for tenement buildings.

Revival:

1949: Sam Wanamaker first visited London to search for the site of the Globe Theatre.

1971: Wanamaker founds the Shakespeare Globe Trust with the mission to recreate the first Globe Theatre as accurately as possible.

1993: Despite persevering for two decades, Sam Wanamaker didn’t live to see the completion of the project he had envisioned, dying in 1993.

1997: Queen Elizabeth II opens The Globe Theatre.

Visiting Today

What to see and do:

Why go:

A visit to the Globe to see a production is like nno toehr you will experience and allows you to more directly touch the lives of the ordinary folk of Tudor and early-Stuart England.

Must-Sees:

Take a Guided Theatre Tour to learn about its history and the history of the original Globe Theatre. If you can, see a show!

Do I have to pay?

Outside of performances, admission is by guided tour only and prebooking is strongly encouraged. You can find out more by visiting this link.

Where to eat and drink:

There is no cafe on site, but the surrounding area has many restaurants and bars within easy walking distance.

How to get there:

- Address: 21 New Globe Walk, SE1 9DT.

- Boat: Thames Clipper to Bankside Pier.

- Tube: London Bridge on the Northern line (9 minute walk); Blackfriars on the District and Circle Lines (10 minute walk); Mansion House on the District and Circle Lines (10 minute walk); Southwark on the Jubilee Line (15 minute walk) and St Paul’s on the Central Line (15 minute walk over the Millennium Bridge, a footbridge over the River).

- Walk over the Millennium footbridge from the City of London, near to St Paul’s Cathedral.

- Train: Blackfriars (10 minute walk, South Bank exit, lifts to street level from platform); London Bridge (15 minute walk).

If you want to know more about nearby London Bridge, which connected Southwark with the city during the Tudor period, you can read more in the Tudor travel Guide blog: London Brige: Traders, Travellers and Traitors – https://thetudortravelguide.com/2019/03/02/old-london-bridge/.

Finally, while you are in the area, you might want to visit a replica of The Golden Hind, Southwark Cathedral and the remnants of Winchester Palace. All are located nearby on the south bank of the Thames, within easy walking distance of one another.

2 Comments