Burying the Tudors: More Tales from Inside the Vault

With the recent death of Queen Elizabeth II, the nation has seen her coffin travel from Balmoral, to Edinburgh to London. A formal ceremony steeped in tradition, Queen Elizabeth II’s body will lie-in-state, alike royal monarchs before her. In this blog, I look back at royal burials, satisfying my insatiable curiosity to uncover everything I could about the burial, and final resting place of, the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty: Elizabeth I.

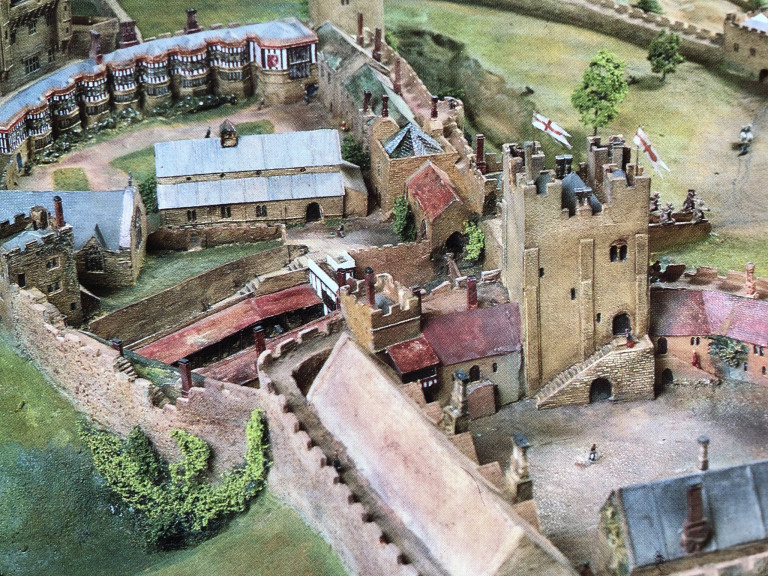

I have a Tudor bucket list. Things imbued with Tudor history that I would simply love to do or see. For example, I would love to explore the perfect Tudor Manor at Compton Wynyates; leaf through the pages of Anne Boleyn’s prayer book, and I would be fascinated to glimpse into the Tudor vaults at Westminster Abbey. It’s slightly macabre, I know, but I have long been intrigued to know more about the Tudor tombs that lie beneath the cold, stone floor of this historic building.

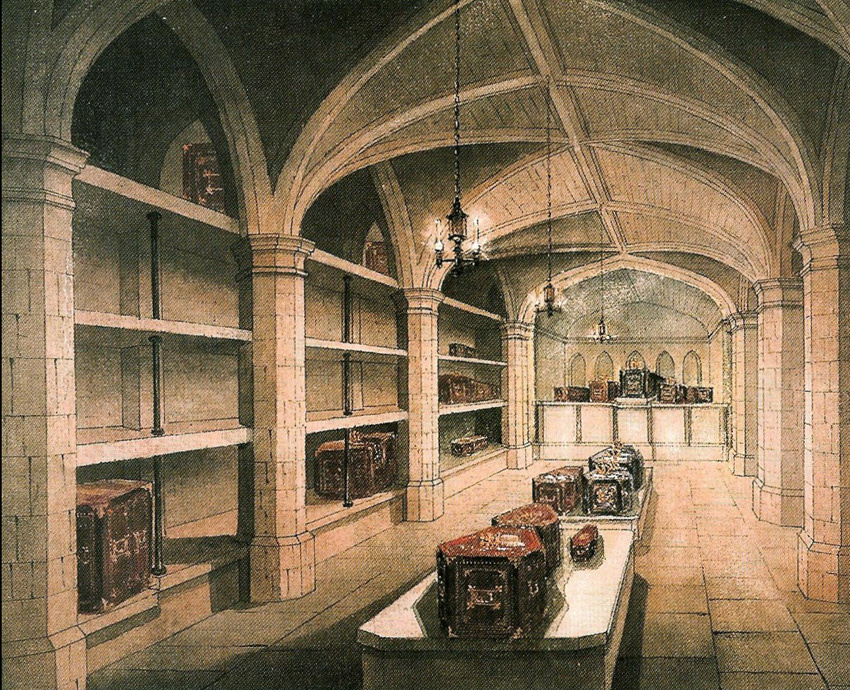

Before I began researching the burial of Elizabeth I for a recent blog, I didn’t even know if the coffins of Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, Mary I, Elizabeth I and Edward VI were even accessible. Were these ghostly graves in large, open chambers that you could walk into (even though they are not open to the public, I should stress) like the one at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, or were they sealed into narrow vaults that were never meant to be disturbed? I realised I wanted to know more about these Tudor tombs, and it was this insatiable curiosity that set me on the path of uncovering everything I could about the burial, and final resting place of, the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty: Elizabeth I.

However, this turned out to be just the beginning! During the course of that research, I found out about the existence of a fascinating Victorian account of the tombs and Westminster Abbey burials. It was written by Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster. This gentleman was tasked with, among other things, finding the body of James I of England and VI of Scotland. He seemed to have gone missing! The accounts of the position of the dead king’s tomb were at odds with one another. So, Mr Stanley set about his quest to unearth – literally – the truth.

The result was a gripping Indiana Jones-esque foray through the narrow passageways and hidden vaults of the abbey. In the course of this adventure, Stanley describes the discovery of the Tudor tomb of Elizabeth I, where her coffin was stacked unceremoniously on top of her half-sister, Mary. However, there was more detail that Stanley and his team uncovered when searching the central area of the Lady Chapel – often known as the Henry VII chapel in honour of the man who commissioned its construction. The details of the rest of the tale are too riveting to be left untold. And so, I am back to complete the story!

Therefore, in this blog, we will focus on the Tudor tombs that lay beneath, and close to, the fabulous monument by Torregiano, erected as a memorial to Henry VII and his, wife, Elizabeth of York. Ironically, as it turned out, this was the very last area of the Lady Chapel to be explored by Stanley and his team. More on that to come, but for now, let’s roll back time to the beginning…

The Tudor Tombs Beneath the Henry VII Chapel Floor at Westminster Abbey

At 2.45 pm on 24 January 1503 (yes, that precise!), the first foundation stone of Henry VII’s new Lady Chapel was put in place. In the process, two old chapels of St Mary and St Erasmus, as well as Chaucer’s garden, were ‘swept away’ to accommodate the magnificent royal mausoleum, whose architecture is simply breath-taking. When you visit, you will be awe-struck by the superb fan-vaulted ceiling, described as the ‘climax of late medieval design’.

There’s no doubt that this most parsimonious of kings always intended that he would be buried alongside his wife in a glorious monument to the Tudor dynasty. Indeed, his intention to have the chapel as a dynastic mausoleum is confirmed by the Latin inscription around his tomb enclosure: that he had ‘established a sepulchre for himself, his wife, his children and his house’. However, I suspect he did not conceive that such a resting place would be required for his queen only one month after the foundation stone was laid!

It is well known that Elizabeth died following childbirth at the Tower of London on 11 February 1503. It was her 37th birthday. Henry’s planned mausoleum was far from complete at the time of his beloved wife’s death. So, she was temporarily interred elsewhere in the abbey. According to Stanley, this was in a side-chapel. Only later would the queen’s body be reinterred next to her husband in a vault beneath Torregiano’s fabulous gilt-copper monument.

However, the chapel was near completion by the time Henry VII died in April 1509 at Richmond Palace. His body was first conveyed to St Paul’s, where obsequies were heard, then on to Westminster for burial. The coffin, covered in black velvet and emblazoned with a white satin cross from ‘end-to-end’, was lowered into a ‘cavernous vault’. The bishops, archbishops, and abbots struck their crosiers [crosses] on the coffin and spoke the words, ‘Absolvimus’ in an incantation reminiscent of something out of Harry Potter! After William Warham, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, had thrown earth into the vault, it was sealed.

We have talked before about the burials of Elizabeth I and Mary I in the north aisle of the Henry VII chapel. Of course, Margaret Beaufort and later, Mary, Queen of Scots, were interred in the south aisle. However, we will now focus on Stanley’s account of the reopening of the central vault. This is the vault in which Henry VII and Elizabeth of York had been interred around 400 years earlier.

The Tudor Vaults are Reopened

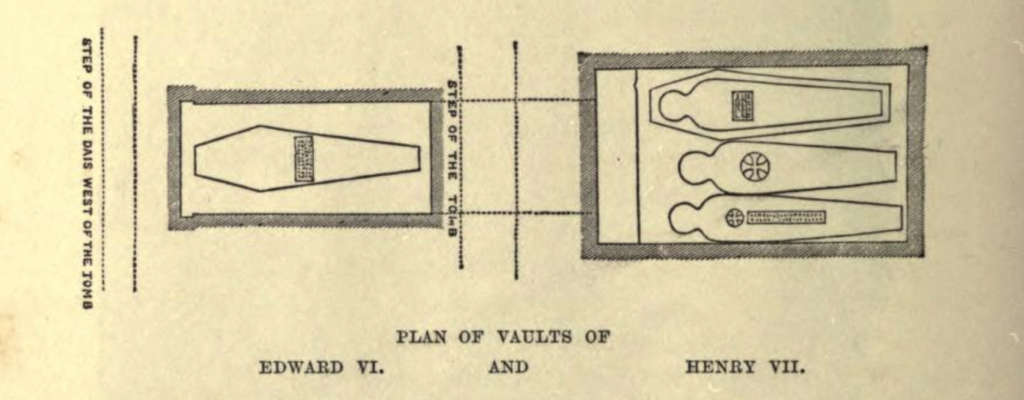

In his ongoing, and as yet fruitless quest, Dean Stanley and his team began to dig directly west of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York’s monument, in an area known to contain the tomb of Edward VI. Immediately, they came across a ‘shallow vault containing one leaden coffin’. He describes its appearance as being ‘rent and deformed as well as wasted by long corrosion and perhaps by having been examined before.’

The narrow vault in which the coffin was buried measured only 7.5 ft long and 2.5 ft wide. It was clear that no other coffin was present. However, Stanley found remnants of the lost Torregiano altar, which had once sat directly in front of the west end of the Henry VII/Elizabeth of York memorial. At the time, this altar was considered to be a ‘matchless’ piece of artistic work by the Italian artist. Steps up to the original dais, and a complete frieze of carved Italian marble depicting heraldic badges of the Tudor Roses and French lilies had survived its destruction, probably by Puritans, in 1641.

Underneath this debris was the coffin, its wooden case had ‘been in part cleared away’. However, at the lower end was the original coffin plate which was ‘loose and unsoldered’ and ‘curiously curled up’. The Latin inscription was indistinct but fathomable in full light, once the plate had been cleaned. Translated it read:

Edward the sixth by the Grace of God King of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith and on earth under Christ supreme head of the churches of England and Ireland and he migrated from this life on the 6th day of July in the evening at the 8th hour in the year of our Lord 1553 and in the 7th year of his reign and in the 16th year of his age.

The sad demise of Henry VIII’s great hope for the Tudor dynasty was recorded to the hour: 8 pm on 6 July 1553. Stanley eulogises about the inscription being the first to declare so emphatically the monarch’s position in direct relation to God as supreme head of the Church in England and Ireland. Unique at the time. After much debate, the plate was placed back into the grave, although the marble frieze, as a work of art, was ‘placed as close as possible to its original position’. However, annoyingly, James I of England remained elusive.

Having exhausted every other possibility, Arthur Stanley and his team turned their attention to the Tudor tomb of the founder of the chapel: Henry VII and his wife Elizabeth of York. He admits that while one account – the Abbey Register – had stated from the start that James was in fact buried alongside the two Tudor monarchs, its veracity had been rejected on account of three things. First, there were other conflicting sources pointing to different areas of the abbey, which seemed to Stanley to be a more likely burial place. Secondly, there was no evidence of disturbance of the marble floor of the chapel near the Tudor tombs, which might suggest that the vault had been reopened in the past. Finally, it seemed so improbable to Stanley that the first Stuart king should lie in the tomb of the first Tudor one, that he had dismissed the possibility out of hand. Consequently, the Tudor tombs known to contain the founder of the Tudor dynasty and his queen consort had been left untouched until all other avenues were exhausted. Perhaps we can be grateful that this was the case. Otherwise, we might well not have the information on the vaults of Henry VIII’s three children.

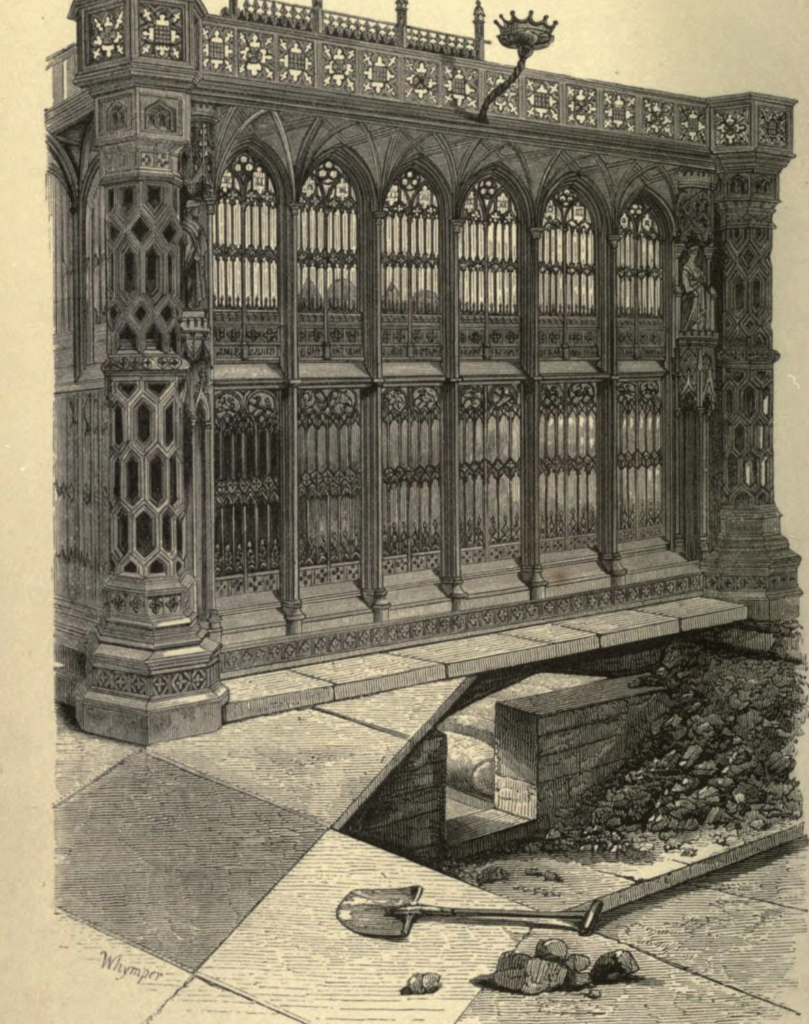

Having carefully examined all sides of the tomb for the most likely entrance point, Dean Stanley describes how his workmen set about opening up a narrow space, close to the vault of Edward VI, to the west of the monument. Immediately, the earth beneath was found to be disturbed, loose and full of bricks. It seemed somebody had been here before!

As the earth was cleared, a stone step was uncovered, and with further removal of debris, eventually, the team encountered a large stone ‘surmounted and joined on the north side with smaller stones and brick-work all over’. As the brickwork was removed, the vertical end of a flat-pointed arch, which was clearly the entrance to the tomb, was exposed. Excitement was building. Can you imagine? You are about to open a tomb that has not been seen in nearly 400 years? At this point, I must let Arthur Stanley speak in his own words, for who better to convey what they were experiencing that day?

It was with a feeling of breathless anxiety amounting to solemn awe, which caused the humblest of workmen employed to whisper in baited breath, as the small opening at the apex of the arch admitted the first glimpse into the mysterious secret which had hitherto eluded this long search.

A light was introduced, penetrating the inky blackness to reveal three coffins; two of them ‘dark and grey with age, the third somewhat brighter and newer’. The two darker ones were leaden, one with an inscription plate. The newer one still maintained its wooden case and also bore an inscription upon the lid.

To enter the tomb, Stanley and his workmen had to remove the loose brickwork at the apex of the vault. The gap – only 12 by 9 inches – had once served as the small man-hole through which the person who had stayed inside the tomb to help move the large stone into place (thereby blocking the entrance) could escape. Ugh! I don’t know about you but I wouldn’t have had that job for all the tea in China!

Stanley’s team measured the vault to be 8ft 10 inches long, 5 ft wide, and 4.5 ft high, with the roof fashioned into the shape of a low Tudor arch. The vault was sunk 5.5ft below the floor of the chapel. Within the vault, the stone floor was in pristine condition. No condensation was noted, suggesting that the coffins had not been affected by corrosion. Stanley recalls how he had been struck by ‘a deadly chill’ when the vault was first opened but, having climbed in, he began to examine, and record, what he found there.

The coffin lying on the north side was immediately identifiable as the elusive James I, on account of the inscription plate set upon the wooden lid. However, as the Stuarts are not my thing, I will focus on the other two burials, which were undisputedly those of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII.

Both coffins were of lead, with the whole of the wooden casing having been removed in both instances. Arthur Stanely concluded that this had been done deliberately during the internment of James I to make space for his body in this snuggly-fitting vault. At this point, Elizabeth’s coffin was moved from the north of the vault into the centre as the third resident was laid to rest.

Each Tudor coffin was shaped at the head and shoulders, then ran straight down. As stated above, Elizabeth’s lay in the centre, a Maltese cross engraved into the lead. To her right was her husband, whose coffin bore a lead inscription plate, running lengthways, which read from west to east. Although my Latin is a bit rusty, here goes with my translation:

Here lies Henry VII, King of England, France and Ireland, who died the 21st Day of April in the 24th year of his reign and in the year of our Lord, 1509.

Our tenacious explorer concludes by noting that the pall of silk known to have been buried with Henry VII; the urns associated with each burial, and probably any other thing of value, was gone. Graffiti etched into the lead, revealed that a certain ‘John Ware’ and ‘E.C’ had been there in 1645 – the year James was interred in the vault. After having recorded that several people associated with the abbey viewed the vault, it was once again closed. At its base, a tablet was inscribed: ‘This vault was opened by the Dean, February 11 1869’. (How curious that it coincided with the anniversary of the death of Elizabeth of York in 1503!)

And so inside these fascinating Tudor tombs, the first ruling Stuart of England took his place alongside the founders of the Tudor dynasty. I suppose James was Henry’s great-great-grandson. So, although not of the same ‘house’, the three bodies that lie entombed in the chilly darkness share common fealty in Margaret, the Tudor princess who ultimately untied the kingdoms of Scotland and England.

The End of an Adventure

As Arthur Stanley’s adventure comes to end, I realise so does my hope of ever getting a glimpse beneath the marble floors of Westminster Abbey. I know that I am never likely to tick ‘seeing the vaults of Westminster Abbey’ off my bucket list. However, at least now I know exactly what, and who lies beneath my feet next time I explore the Tudor tombs of the awe-inspiring Henry VII Chapel. But what about you? What Tudor tombs most intrigue you and what’s still on your ‘bucket-list’?

If you wish to read more about the death and burial of Elizabeth of York, follow this link. If you want to find out about the location of other Tudor tombs, On the Tudor Trail has a comprehensive list here.

If you have enjoyed touching the past through this blog, do remember you can subscribe to my mailing list to receive all the latest news on new blogs, podcasts, videos and in-person events by clicking this link.

Notes:

This information in this account comes from the Historical memorials of Westminster Abbey by Stanley, Arthur Penrhyn, 1815-1881.

Notable Tudor figures and relatives buried in the abbey include: Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, Margaret Beaufort, Edward VI, Anne of Cleves, Mary I, Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots, and James I.

Thank you for this very interesting article

You are welcome! Thanks for dropping by and reading.

I have been interested in Tudor history since I was 13. Today I turned 65. Love your articles. Would love to visit England but will need to be satisfied with pictures.

Thank you! So glad you could be here.

An interesting and fascinating account. I also thought it was well illustrated. I am an avid reader of Tudor history and have amassed quite a collection of books over the years. This is an area , certainly in this detail is rarely touched. Thank you.

Am honoured by your comments. Thank you, Barry!

I just downloaded Arthur Stanley’s book on the WA vaults not realizing it’s over 600 pages. I need a cooy or at least a print out of Chapter III, Royal Burials. It’s fascinating. I fall into a trance in the Henry VII Lady Chapel every time.

Well, that will keep you busy! : )

This is amazing, I have always been fascinated by the Tudor tombs and graves too. I would love to know more about Henry VIII and Jane Seymour’s tomb, we have one sketch showing the tomb and the damage to Henrys coffin and debris, it would be fascinating look again

I too have been fascinated about Tudor period, I have been to Hampton court palace, Westminster Abby. I

Have always felled sorry for Catherine of aragon, for the way Henry treatreated her, I have to say my favorite is Ann Boylan, since she didn’t give him a son, de he really have to kill her. I believe they really did love each other. I could not have lived in that period. A love of Tudors, you must love things that are 500

Years old

Thank you! I attended the University of Massachusetts. Boston where the library archives had a 1st printing of Stanley’s “Westminster Memorials”. As a History/Education major, I would pour over it for hours at a time. Always wondered about the final resting place of Edward VI. Much has been written about his illness & death. Conspiracy theories still abound about the final days of the last Tudor king & first Protestant one as well.

Fascinating stuff! The introduction of the remains of James I into the Henry VII/Elizabeth vault seems a strange choice to me also! ?

Fascinating, Thank you, Wonderful articles on the Tudor graves and Stuart

I have been student of Tudor History awhile. and learn something new every day ??

I love that! Thanks for reading the blog ?

I truly believe King Edward the Sixth was poisoned. over a prolonged period.

possibly by by the duke of Norfolk.

Question .thomas more, thomas cromwell and all of KHVIII Victims. were they buried honrably within the chapel tomb .

or just thrown inside.. Coming from New Zealand and been fortunate to have over the past decades visited the tower ,Chapel, and read the list of names interred if tomb matched

st Georges at Windsor,

None of the experts even give mention in the documentries.

Perhaps in time my query will find an answer.

Thank you so much for sharing your tudor world,

Michael Deauchamp

A Tudor student

.

Hi Michael, They were all buried with Christian rites, I believe, although in different places in the chapel of St Peter (if you are talking about those who were executed. I know More’s remains are in the crypt of St Peter’s at the Tower and many of the noblest, including Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, are in front of the high altar. Thanks for your kind words. PS Have you read my blog on the burial of Anne Boleyn (and others) in the Tower? https://thetudortravelguide.com/2021/05/18/the-burial-of-anne-boleyn/