A Tudor Weekend in Monmouthshire

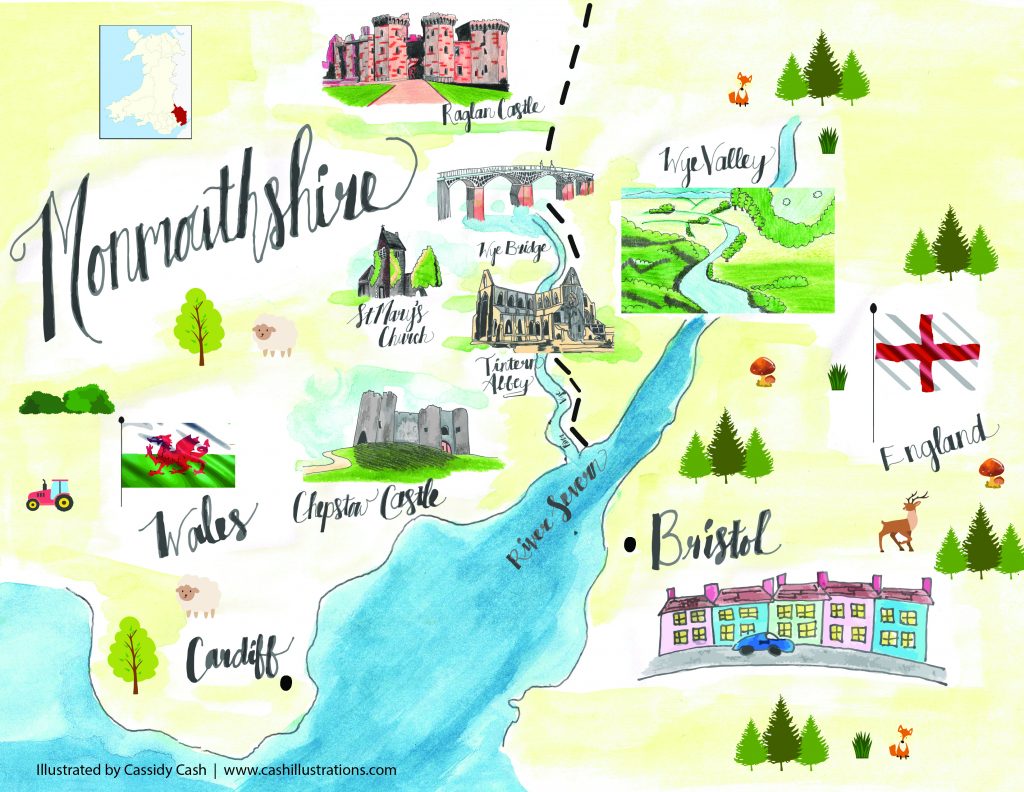

Monmouthshire in South East Wales is a delightful area to visit. Two locations included in this itinerary are in the Wye Valley, just inside the Welsh border, in an area considered to be of outstanding natural beauty.

This two-day itinerary will take you to visit two fabulous castles and a ruined abbey. Chepstow Castle has deep roots in early medieval history, while Raglan was created as a luxurious palace-fortress during the fifteenth century by the powerful Herbert family. Its connections to Henry VII make it a must-see location for anyone interested in early Tudor history. Finally, you can drive or walk to the idyllic Tintern Abbey, renowned for the beauty of its location, adjacent to the River Wye.

So, let us go exploring three wonderful Welsh locations…

Your Weekend Itinerary

Arrive Friday evening

Saturday

Morning: Raglan Castle

Lunch: A packed lunch at Raglan Castle or return to Chepstow for lunch by the river at The Boat Inn.

Afternoon: Chepstow Castle

Round off your busy day sightseeing with a cup of tea and cake at Marmalade Vintage Tea Rooms.

Sunday

Morning: walk along the Wye Valley from Chepstow to Tintern (around 5 miles).

Lunch: The Rose and Crown, Tintern (booking essential).

Afternoon: Tintern Abbey and possibly the ruined St Mary’s Church

Return by bus to Chepstow. There is a direct bus departing from Tintern Abbey to Chepstow Bus Station. Services depart every two hours and operate every day. The journey takes around 16 minutes.

Alternatively, drive to Tintern. There is ample parking onsite, adjacent to the abbey.

Cadw manages all the sites mentioned in this article. Members of Cadw go free. If you have an English Heritage membership card, you can get free entry or use it to purchase tickets at a reduced price at many Cadw properties.

Chepstow Castle

Chepstow Castle was founded on the north bank of the River Wye by William Fitz Osbern, a French nobleman who came to England with William the Conqueror after the Norman invasion of 1066.

Building began in 1067, with the mighty castle being constructed on a plateau of a craggy cliff overlooking the River Wye on the Welsh side. This tidal river meanders through the eponymous valley, separating England from Wales. From here, Chepstow Castle could control this unruly part of the country and the flow of goods up and down the watery highway below.

Although in ruins today, the castle remains an imposing sight and is best appreciated from the early nineteenth century iron bridge spanning the River Wye. Its four baileys (or courtyards) rise with the contours of the land, from the gatehouse and Lower Bailey in the south, through the Middle and Upper Baileys to reach the thirteenth-century Upper Barbican in the north.

The earliest part of the castle is its breath-taking Norman, Great Tower, sandwiched between the Middle and Upper Baileys. This chamber block is the earliest example of its kind in England, providing accommodation for the early lords of the castle and their families. While the roof and interiors are gone, exquisitely carved masonry fragments survive. These give a glimpse into the lost elegance of these high-status chambers.

The revered William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke and Regent for the young Henry III, was the next owner of Chepstow Castle to leave his mark. He was responsible for aggrandising the castle by constructing the current main gatehouse and much of the curtain walls of the Middle and Upper Baileys in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.

When you visit the castle, you’ll find some of the most exciting features clustered around the first courtyard, also known as the Lower Bailey. Here, Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk (also the nobleman responsible for constructing Framlingham Castle), developed some of the castle’s finest buildings. In the thirteenth century, the Earl ordered the installation of a new privy lodging range. This included the kitchen and cellar on the lower floors, with the great hall and privy chambers on the upper floors. Explore the wine cellar for a fine view over the Wye Valley – there is a great photo opportunity if you want to capture something a little moody.

Across the courtyard stands the Marten Tower. Bigod probably intended this to be used as high-status guest lodgings, perhaps even for occupation by the king. Its presence was a sign of the Earl’s status and high standing with his monarch, Edward I.

While much of the castle’s history is dominated by its medieval Marcher Lords, there is still some Tudor History of note. This history is woven into the castle’s fabric and the story of the most dominant aristocratic family of the period: The Earls of Worcester.

As with Raglan, Chepstow Castle came into the ownership of the Earls of Worcester through marriage in 1508, when the heiress of both properties married Charles Somerset, later the 1st Earl of Worcester. Charles was a prominent courtier under Henry VII and his son, Henry VIII. It would be Charles’s daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, the Countess of Worcester, who would set the wheels in motion that would eventually destroy the Boleyn faction in 1536.

Charles instigated the first major redevelopment of the fortress since the time of Roger Bigod. His focus was on the Lower Bailey, which he turned into a more fashionable Great Court. The Earl retained the thirteenth century great hall installing new, Tudoresque fireplaces and windows. It is easy to see these sandstone features when standing in the Lower Bailey and admiring the exterior of the remodelled privy lodging range.

The most significant addition was a connecting range that ran from the north side of these medieval lodgings via new first-floor chambers adjacent to the gateway that divided the Lower Bailey from the Middle Baileys. While all these latter Tudor structures have gone, you can still see the unmistakable remains of Tudor fireplaces hewn into the dividing curtain wall.

When visiting Chepstow Castle, you must note that the Upper and Middle Bailey gateway doors are still in situ. Both of these are Tudor. However, the pièce de résistance is Europe’s oldest known castle doorway. It was once the gateway of the main gatehouse and has been carbon-dated to pre-1190. You can see this gateway inside the privy lodging range in the Lower Bailey, where it has been brought undercover to protect it from the worst weather. If only those doors could talk.

Before you move on from Chepstow, there are a couple of other historical sites to see. The most significant is The Priory Church of St Mary, where Elizabeth Worcester, the aforementioned wife of Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester, is buried. While visiting Chepstow, I tried to access the church and found it locked up. I recommend contacting Chepstow Parish to check when the church is open before your visit.

The only surviving gateway to the old town is to be found at the top of the High Street. This structure is Tudor, having been rebuilt from the deep pockets of Charles Somerset.

Places to eat and drink in Chepstow

My favourite tea room was Marmalade Vintage Tea Rooms at the top of the High Street, near the surviving Tudor gateway into the town. For lunch, try The Boat Inn, just a 5-minute walk from the castle. It is a characterful pub. The food is basic but adequate.

Raglan Castle

The magnificent castle at Raglan exists today thanks to a Welshman from a minor gentry family. His name was William ap Thomas. The story of this family is entwined with the bloody struggle for the English throne in the mid-fifteenth century, a struggle we know today as The Wars of the Roses.

Raglan was situated in a strategically important spot close to the border with England. This border area was renowned for its lawlessness and was ruled over by the so-called ‘Marcher Lords’. By the mid-fifteenth century, they oversaw the region on behalf of the English Crown.

William ap Thomas married well; two wealthy heiresses provided the money that allowed him to begin building a grand, new house on the site of an earlier medieval fortress. His son, another William, would complete the job. He left behind a magnificent palace-fortress whose architectural splendour and size rivalled any royal residence of the period.

The younger William restyled himself, anglicising his family name to ‘Herbert’. His fate would be inextricably linked to the English Crown for the remainder of his life.

In 1442, William ap Thomas died, leaving his elder son to inherit the family title and lands. William the Younger began his career by fighting with English forces in France. By the 1450s, he was a vassal of Richard Neville, also known as Warwick the Kingmaker. The latter was thus styled because of his pivotal role in securing the future Edward IV his throne.

At this time, Neville owned land in south-east Wales. He appointed William Herbert to protect his local interests. Herbert allied himself with the interests of the House of York. However, Herbert’s allegiance to York was, shall we say, ‘flexible’. As the protracted tussle for power grumbled on through the 1450s to the early 1470s, William Herbert choreographed a delicate dance between the Houses of York and Lancaster. At one point, he was even knighted by the Lancastrian King, Henry VI, alongside the latter’s half-brothers, Jasper and Edmund Tudor.

William Herbert was fighting for the Yorkist cause, alongside Edward, Earl of March, at the decisive battles of Mortimer’s Cross and Towton. The bloody battle saw the House of York seize the throne, and the Lancastrian forces routed. The new King Edward IV showed his gratitude to William by endowing him with wealth and status. He was knighted at Edward’s coronation, becoming Sir William Herbert. William was now an extraordinarily influential and wealthy man at court, and Edward entrusted his loyal servant with ruling Wales on behalf of the Crown.

Even though the House of York now held the Crown of England, pockets of stubborn Lancastrian resistance remained, notably in Northumberland and Herbert’s home country, Wales. William Herbert was assiduous in the task, laying siege to two notable, Lancastrian strongholds: Harlech and Pembroke Castles.

At the time, Pembroke was the home of Jasper Tudor, the half-brother of the deposed King Henry VI and the guardian of a young Henry Tudor. William Herbert laid siege to Pembroke when little Henry was just four years old. The castle fell, and Jasper Tudor fled abroad, leaving Henry behind. The young boy was taken by Sir William, who acquired Henry’s wardship from the king in return for paying a large sum of money to the Crown.

For seven years, Henry Tudor lived at the castle as a ‘prisoner’ (Henry’s own words, uttered much later once he was king). However, he was treated more like a welcome house guest, learning from the best tutors that money could buy, alongside Sir William’s two sons, Walter and (another) William. The bonds of friendship forged between these young boys in the schoolroom at Raglan would see Walter Herbert fight alongside Henry and the Lancastrian cause many years later at the Battle of Bosworth.

Henry’s stay at Raglan as the ward of Sir William ended on the latter’s death in 1469. Sir William was brutally put to death on the orders of Warwick the Kingmaker, a former friend, now turned mortal enemy, following the Battle of Edgecote, near Banbury in the English south Midlands. His body was eventually conveyed to Tintern Abbey and laid to rest in the abbey church.

Architecturally, the building work at Raglan flourished during Sir William’s guardianship. He continued the work started by his father and is credited with building the impressive gatehouse, flanked by striking octagonal towers and embattled machicolations. He probably constructed the distinctive octagonal keep as the last line of defence in case of attack from his arch-enemy Richard Neville or the Lancastrian forces. With a kitchen on the ground floor and a well to access fresh water, Sir William and his family could retreat to the tower and be self-sufficient for some time if the castle was ever besieged.

While distinctive defensive features are associated with the castle, there is no doubt that Raglan was a luxurious residence built by stonemasons of the highest calibre. An integrated series of guest suites consisted of two or three chambers each, accessed by an elegant processional stair. You can still see the fine stone carved windows and a state-of-the-art garderobe tower near the principal privy lodgings. These features speak of the sumptuous comforts enjoyed at Raglan by Sir William, his family and honoured guests.

The castle is accessed by the gatehouse, which leads into the first of two courtyards. The outer courtyard at Raglan is known as the Pitched Stone Court. In keeping with any outer courtyard of a castle or Tudor palace, it was surrounded by service offices and kitchens. A prominent feature is a porch, which draws us in to explore the lower end of the great hall. This occupied a central part of the cross-range that divided the outer from the inner courtyards.

Like all the buildings at Raglan, the great hall is now roofless. The screen, and hence any pre-existing screen’s passage, has gone. But the scale of the hall is clear. Here, Sir William Herbert spent his last evening at Raglan feasting with his comrades before setting off to the Battle of Edgecote.

Other notable architectural features common to any great hall of the period can also be seen here. The towering oriel window that once illuminated the high end is a fine feature. The passages leading to the pantry, buttery and the kitchen at the lower end are still intact. However, the door leading to the privy lodging range at the high end is gone. Through this gaping hole, the lord and his lady would have retired to occupy a suite of rooms looking out over the moated keep on one side and the inner courtyard on the other.

This courtyard was known as Fountain Court because of the fountain at its centre. Here, you will also find the footprint of the chapel. Standing in the chapel with the hall on your right, look up to see the remains of a Tudor window. This was once sited at the end of the Tudor long gallery. Unfortunately, the window is all that remains to speak of its presence at the castle.

Finally, enjoy the gorgeous processional stair in the far corner of the courtyard. This led to the guest suites. Views from the tower here, and those at the top of the keep, provide some of the most dramatic photo opportunities of the castle’s ruins and surrounding countryside.

Raglan is a spectacular place to visit, and as one of the childhood homes of the future Henry VII, it is a significant place for any Tudor enthusiast.

Places to eat and drink at Raglan

There is no cafe at Raglan Castle, although you can pick up water bottles and cans of drink and ice cream from the visitor centre. There are toilets on-site. There is a large grassy area with a handful of picnic tables. With a view of the castle and the surrounding countryside, this makes for a lovely place to enjoy a packed lunch.

There is parking on-site, adjacent to the castle.

Tintern Abbey

When you visit Tintern Abbey, you will be walking in the footsteps of thousands of people who have gone before you and have made the pilgrimage to visit this glorious ruin, celebrated across the centuries for its peaceful isolation and romanticism. Famous English painters, such as J M W Turner, have captured its crumbling, ivy-covered walls and poets, such as William Wordsworth, have been enraptured by its breathtaking beauty and the timeless serenity of its surroundings.

Arrival by boat was once the only reliable way to reach Tintern Abbey. Today, good road connections have facilitated many more tourists reaching the area. Although it can get busy, the setting for this ancient, monastic property remains charming. It is easy to see why the Cistercians, who sought withdrawal ‘from the conversations of man’, chose this spot.

Tintern sits just on the Welsh side of the Welsh/English border, in the heart of the picturesque Wye Valley. On either side of this valley, and towering over the abbey, are lush, wooded escarpments that rise to lofty hilltops, while the River Wye meanders along the valley floor adjacent to the abbey.

In many ways, the life and decline of Tintern Abbey are no more remarkable than any other medieval monastery that was founded in the early medieval period, flourishing under wealthy patrons (many of whom are buried in long-lost graves inside the abbey church, including that of the executed William Herbert, whom we met at Raglan Castle), before being smashed by the power of the Tudor state during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It is of some note for being only the second Cistercian monastery to be founded in the British Isles (and the first in Wales), after the Cistercian abbey of Waverley in Surrey.

Luckily for us, substantial ruins remain behind, despite the fabric of the building being torn apart during the sixteenth century and the site later being used as a wireworks. The most impressive of these ruins are the remains of the late twelfth/early thirteenth century Gothic church. This was constructed thanks to the deep pockets of its then patron, Roger Bigod, who we first met at Chepstow. The spiritual lives of the Lords of Chepstow were intimately bound up with the monastery’s history, which lies five miles upstream from the castle.

Walter Fitz Richard de Clare, the Anglo-Norman Lord of Chepstow, was responsible for founding the abbey on 9 May 1131. The early abbey was simple in design and reflected the spiritual aspirations of the early order. It was served by a Romanesque-style church, with its clean and austere style. Today, all trace of that church is gone, for in the late thirteenth century building began on the much more flamboyant Gothic church, whose ruins we can enjoy today.

The abbey flourished across the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with the size of the abbey complex increasing over time. An original cloister was supplemented with a smaller infirmary cloister. The imprint of both of these can easily be made out when you visit today, although, unfortunately, the exquisitely covered walkways, with their syncopated arches, proved too fragile to survive the passage of time.

By the late middle ages, many of the original buildings had also been expanded; a large infirmary was built alongside a warming house and sumptuous abbot’s lodgings.

Despite Tintern being the wealthiest abbey in Wales, the Valor Ecclesiasticus estimated the value of the monastery to be just under £200 a year. This made it a target of the first Act of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, aimed at the smaller religious houses. Despite having more than the required number of monks and lay brothers, Tintern Abbey was closed on 3 September 1536.

Not all Lords of Chepstow Castle had such a harmonious relationship with the brethren of Tintern. During the first twenty years of the sixteenth century, Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester, seems to have been a proverbial thorn in the side of its then abbot, Richard Wyche. Wyche had previously sought to temper the Earl’s covetous ambitions concerning the abbey estates by bringing a list of grievances against him in the Star Chamber. In the end, the family won the day. Like many local leading nobles, they profited from the abbey’s closure, with Charles’s son, the second Earl, Henry, being granted the property shortly after its closure and after all the precious items had been sent to the King’s Treasury.

Making the most of your visit today…

If you are there as the doors open at 9.30 am, you will likely have some precious time alone to enjoy the abbey’s remains and soak up its charms. The wonderful thing about Tintern is that dogs are warmly welcomed at the abbey and in local cafes and pubs.

After visiting the abbey, you might want to make the short but steep climb along an overgrown cobbled road that leads up to the ruined church of St Mary. This was a monastic retreat for the abbey and later became Tintern’s parish church. Sadly, the church was ravaged by fire in 1977. Today, its overgrown churchyard is roughly tended, and a plethora of higgledy-piggledy tombstones lead up to the entrance porch. It is possible to push open the wooden door and explore the interior of the body of the church. It is roofless and derelict and long since consumed by nature. It’s a haunting spot. The climb up to the church gives some lovely views over the valley.

From here, you can see a footbridge over the River Wye that takes you onto the Gloucestershire side of the valley. One of the locals assured me there is a lovely five-mile walk along the valley to Chepstow. If you’re a walker, I could imagine a walking tour from Chepstow to Tintern, sightseeing with a hearty lunch at The Rose & Crown before heading back to Chepstow on foot or by bus.

Much of the abbey church is roped off currently. Although you can see the church’s interior, you cannot roam freely through it. The staff in the visitor centre explained that the sandstone is crumbling away, and falling masonry has required them to limit access. Restoring the church’s fabric may take some time, so do not expect this to be resolved any time soon. The old iron footbridge across the River Wye closed in June and will remain so for several months for urgent repair work.

Despite this, Tintern Abbey and its surroundings remain charming and make for a pleasant half-day visit.

Accommodation Suggestions

I stayed at The Coach House, a charming little Airbnb just on the outskirts of Chepstow. It was very well situated to access the town (by car) and was extremely comfortable for two people.

Alternatively, if you wish to stay in the heart of the Wye Valley, try Parva Farmhouse, a highly rated B&B in Tintern village, within walking distance of the abbey. Note: this seems to be rated highly, although I haven’t stayed there myself.