The Death and Burial of Elizabeth I: Hidden Tales from Inside the Vault

With the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II yesterday, I couldn’t help thinking of the demise of her namesake, some 419 years ago: Queen Elizabeth I. What struck me in revisiting this blog in light of these historic events, was the parallel between the impact on the people of these islands to the end of both of these long-reigning monarchs. Each embodied the best of what it meant to be English / British in their respective centuries.

The Death of Elizabeth I

What I discovered in writing this blog sent tingles up and down my spine. I love finding out details that are new to me, no matter how small! So, I was curious to find out more, not just about the death and burial of Elizabeth I, which has been well-covered by many writers, but about Elizabeth’s final resting place in the hidden vaults of Westminster Abbey.

The vaults are so inaccessible that my curiosity has hounded me gently for quite some time to go in search of any little-known detail that I might be able to unearth. What do we know of the actual place in which Elizabeth’s coffin is buried? Has the coffin been seen in recent times? What does it look like? Questions, questions, so many questions! Well, I went hunting, and thanks to some guidance from the Westminster Abbey library, I was led to a text that has given me far more than I was hoping for. It felt like I was opening up a whole, hidden world that has not been widely accessed for 130 years. Yes, thanks to the Victorians, I can now answer all my hitherto pressing questions. What to find out more about the death and burial of Elizabeth I? Read on!

The Decline of Elizabeth I

When Elizabeth I died in the very early hours of 24 March 1603, the sun finally set on the age of Gloriana. Indeed, a monumental era in England’s history was at an end. Even her contemporaries speak of how ‘strange’ the common folk of the realm found the name of ‘king’ when James VI of Scotland was proclaimed as her successor, just hours after her demise. There was to be no dynastic struggle, no bloodshed; just immense shock, sorrow and grieving for the only monarch many living in London at the time had ever known – for her reign of 44 years and 4 months was, at the time, ‘a far greater part of a man’s age’.

How did Elizabeth I die?

Elizabeth’s decline into ill health is noted by the chronicler, William Campden, as being from January of that year, 3 months before her death. He recorded how the queen, who had always enjoyed ‘health without impairment’, (which interestingly he attributes to her ‘abstinence from wine and a temperate diet’) became aware of ‘weakness’ and ‘indisposition’ in her health. On an icy and rainy January day, Queen Elizabeth I of England left Westminster for the last time. She travelled to Richmond to ‘refresh’ herself.

However, it was to be of no avail. This was indeed the beginning of the end for the 69-year-old queen. Her descent into despair and physical decay were inexorable from that point forward. As time went on, she spent increasing amounts of time in prayer and would speak only with the Archbishop of Canterbury, John Whitgift, and the Bishop of London, who encouraged her to turn her mind to God.

Interestingly, during this period, Elizabeth asked that her inauguration ring, which symbolised her marriage to England, and which she had worn since the day of her coronation, be ‘filed off her finger’ as it was ‘so grown into the flesh’. Ouch! I guess this means that no ring was actually taken off Elizabeth’s finger upon her death (as I have so often read before). The Tudors, a superstitious lot, saw this as a bad omen; with the physical removal of the ring, Elizabeth’s contractual obligation to the country was ended – and that ‘the marriage would be dissolved’. This being interpreted as heralding her imminent death.

Camden notes some of the physical and psychological symptoms as the end drew near: the ‘almonds’ in her throat swelled (her glands, I presume). Although that quickly subsided, her appetite soon began to fail. Eventually, she fell into a deep ‘melancholia’ and ‘she seemed much troubled by a peculiar grief’. Camden hypothesises many different potential reasons for her grief, but perhaps it was enough that she was old, indeed ancient for her time, and had seen many of those whom she had grown up with, trusted and loved, die before her.

Elizabeth was letting go of an extraordinary life.

By March, the queen fell into a ‘heavy dullness’; she would not speak, her throat was dry and sore, and she gave herself over to her ‘mediations’, allowing the archbishop to pray for her. As death approached, her Lord Keeper (Sir Thomas Egerton) and Secretary, (Robert Cecil) begged the dying queen to name her successor, which she did in a ‘gasping breath’: it was to be James VI of Scotland.

The Death and Lying-in-State of Elizabeth I: Richmond and Whitehall Palace

We know that Elizabeth I died in her privy chambers at Richmond Palace. The palace was just over 100 years old at the time. It had been rebuilt in 1501 by her grandfather, Henry VII, following a disastrous fire that largely destroyed the building in December 1497. Sited on the south bank of the Thames, some 10 miles or so upstream from Westminster, a Tudor herald noted its pleasant surrounding, ‘set and builded between divers high and pleasant mountains in a valley with goodly fields, where the air is most wholesome.’ No wonder Elizabeth sought refuge there as her health began to fail.

The privy lodgings were three-storeys high and built around a central courtyard; the principal chambers of the reigning monarch, which included Elizabeth’s private rooms one presumes, were on the first floor. One account, written 3-4 years after the queen’s death, comes from Elizabeth Southwell, a 16-17-year-old maid of honour in attendance upon the queen during Elizabeth’s final days. She confirms the queen resided in her ‘privy chamber’.

Elizabeth made it clear that she did not wish to be disembowelled following death (as would be customary). Yet shortly after the queen died, Rober Cecil left orders with the surgeons to do so, while he went to London to proclaim James VI the new King of England. And so the queen was embalmed and her body transferred to a lead-lined, wooden coffin.

Elizabeth’s body lay in state at Richmond (perhaps in the chapel – for similar, see Prince Arthur’s lying in state at the chapel in Tickenhall House) for several days before being transferred to a barge and brought downstream to the Palace of Whitehall. Elizabeth Southwell describes that the coffin, draped in velvet, was watched every night by ‘six several ladies’. No location seems to be given for the queen’s continued obsequies, but again, perhaps we might confidently assume that the chapel would have been the most appropriate place.

‘The queen did come to Whitehall by water, The oars at every stroke did tears let fall.‘

During the period in question, Southwell reports how there was a loud ‘crack’ from the coffin as Elizabeth’s ‘body and head’ broke open from the pressures of gases released as the corpse rotted. While the force of the explosion splintered the ‘wood lead and cere cloth’, people speculated on how much worst might it have been if the body had not been opened and disembowelled after death! It is interesting isn’t it, that the story of this event occurring after the end of Henry VIII is much repeated, and seen as a sign of his obesity and gluttony. But here we have the same thing happening with his daughter, who was not subject to such vices!

The Funeral of Elizabeth I

On 28 April, a little over one month after her death, Elizabeth’s body was conveyed in a grand procession down King Street (which today is known as Whitehall) to Westminster Abbey for burial. A complete list of all those persons taking part in this most solemn procession is preserved. Clearly, numbers run into hundreds, from poor men and women to trumpeters, members of Elizabeth’s household, to ladies-in-waiting, knights, squires, other gentry and nobility. The ‘Lady Marques of Northampton’, Helena Snakenbourg, acted as Chief Mourner.

‘The City of Westminster was surcharged with a multitude of all sorts of people in their streets, house, leads and gutters that came to see the obsequies… there was such a general sighing, groaning and weeping as the like has not been seen or known in the memory of man.’

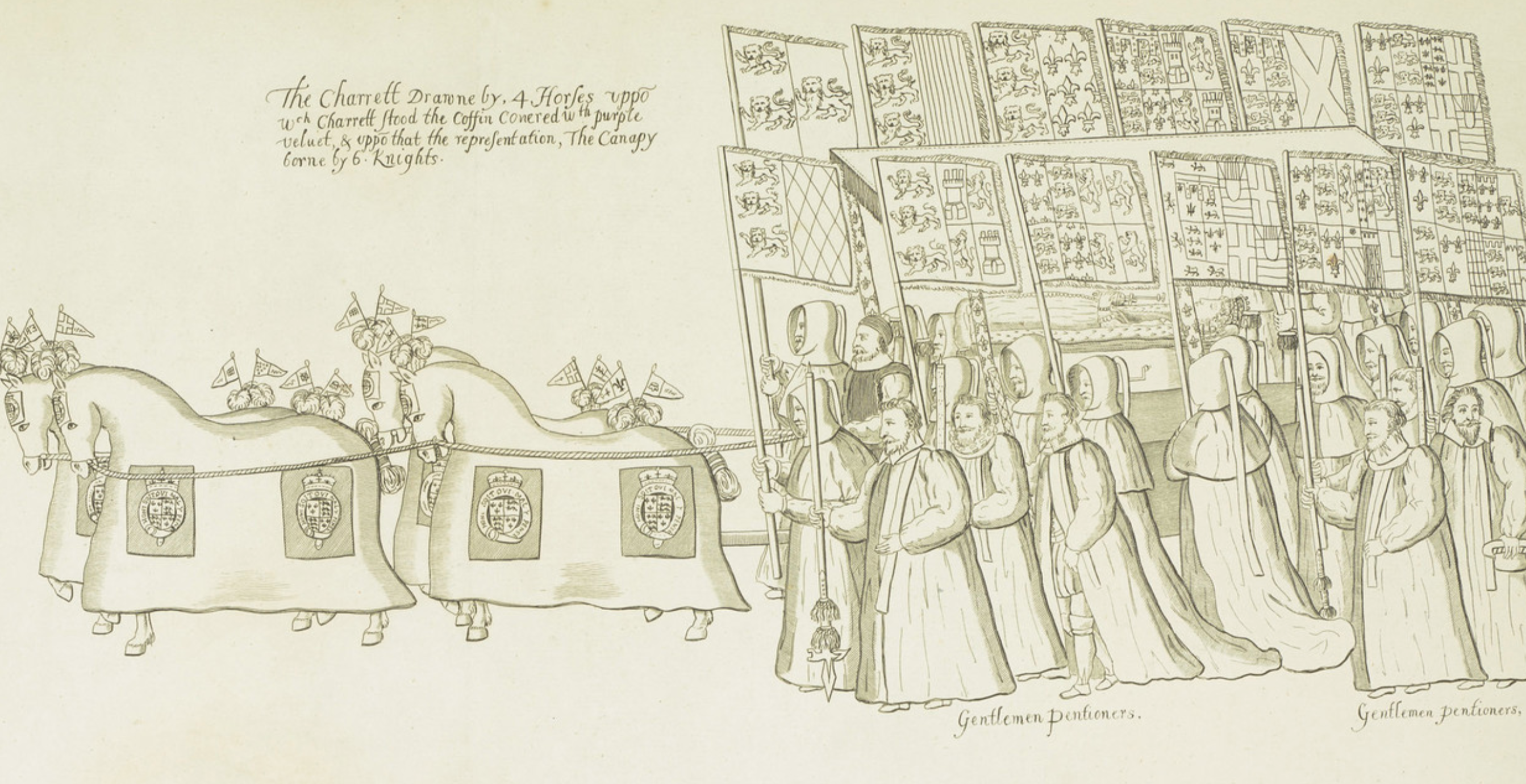

Perhaps most fascinating are the drawings of the procession, which show the hearse and likeness of the queen in some detail. John Nicols’ collection of contemporary documents entitled, ‘The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth’ describes the ‘lively’ effigy of the queen’s ‘whole body’, dressed in her parliament robes with her crown on her head and sceptre in her hand. The image rests atop Elizabeth’s coffin which is covered in purple velvet. This, in turn, is pulled by four horses trapped in black. A canopy is borne over the hearse, while noblemen carry twelve banners, six on either side of the coffin. ‘The Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey’, states these were ’emblazoned’ with the emblems of the House of York, but excluded those of Lancaster.

Stanley describes how Dean Andrews conducted the funeral service, before Elizabeth’s coffin was carried to Henry VII’s chapel. Initially, Elizabeth’s body was deposited in the vault occupied by her grandfather and grandmother, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. However, in 1607, her coffin was moved to the same location as her half-sister, Mary; a protestant princess to be interred alongside her Catholic half-sister. There is a note in the Westminster accounts sheet for 46 shillings and 4 pence for the ‘removal of the queen’s body’ to her new resting place. A magnificent monument, costing £1485 (about 1.5 times the income for a nobleman for a year) was commissioned by her successor, James I. It was carved in white marble and symbolically was smaller than the later monument that the new king erected for his mother Mary, Queen of Scots, on the south aisle.

Interestingly, although the likeness we see today is plain white, according to the Westminster Abbey website, it was once painted. An image, discovered circa 1618-20, ‘shows the queen wearing an ermine-lined crimson robe with a blue orb in her hand, a coloured dress and flesh colouring on her face. The four lions at each corner of the effigy were gilded. No trace of this colour now remains’. But here’s where it gets really exciting…

I came across a book written by Arthur Stanley, published in the 1880s. He had been given permission to survey all the tombs in the abbey by the then-queen, Victoria. It makes for fascinating reading since the crypt in which all royal burials are deposited is closed and I have never read anything specific regarding the Tudor tombs that lie beneath the abbey floor. However, Stanley gives us a glimpse inside these hidden vaults.

In trying to find the actual coffin of James I, Stanley explored a narrow aisle located underground between the eastern end of Elizabeth’s monument and those of James’ own infant daughters. He had already looked in this area before; it was empty and seemed of little interest. However, upon closer inspection, Stanley found a tiny aperture in one of the walls. Upon peering inside, he saw a narrow vault containing two coffins, one placed upon the other. Because I have never read this account before, I am going to include it in some detail.

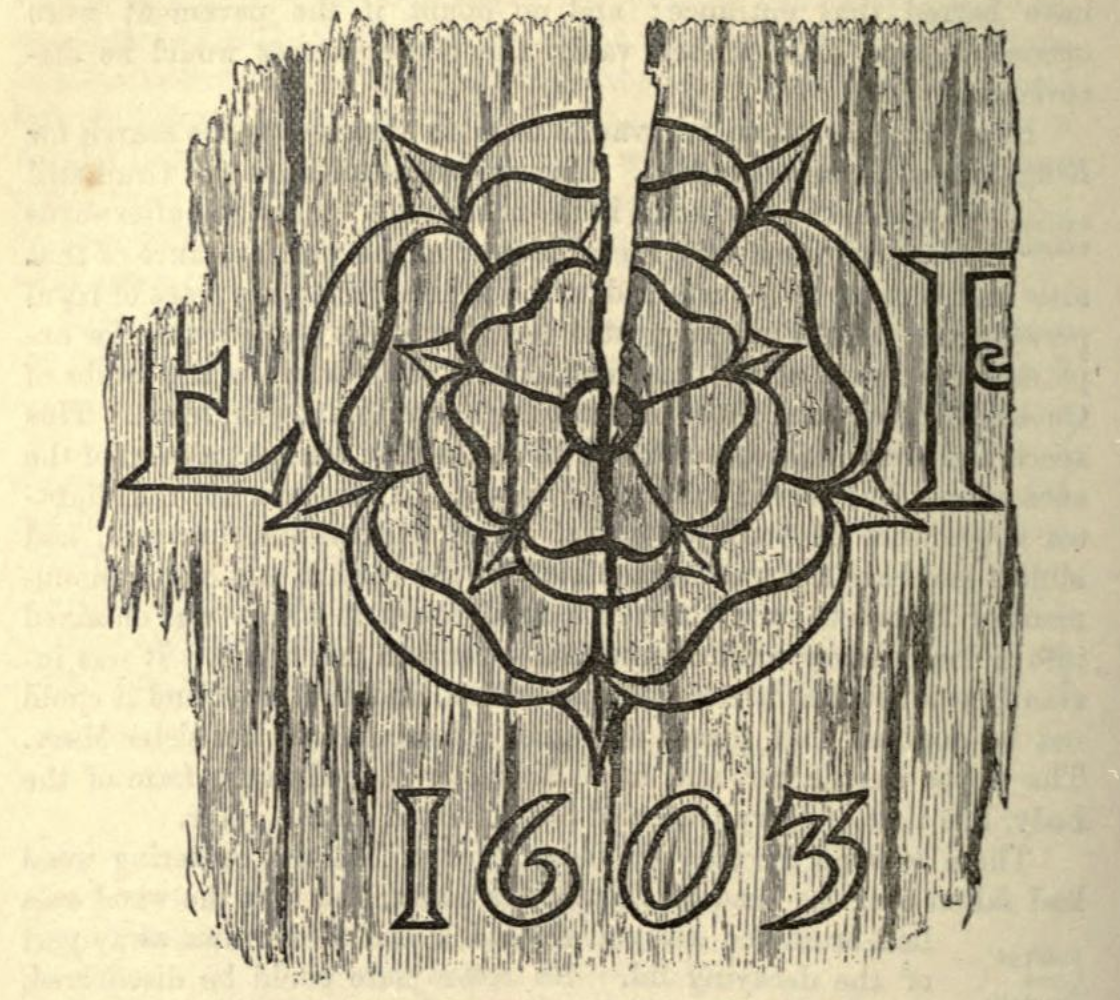

Our intrepid adventurer describes the scene: there was ‘no disorder or decay’ except the ‘centring wood’ at the head of the uppermost coffin had fallen in, and some of the sides were crumbling, which had ‘drawn away part of the decaying lid’. Although no coffin plate was present, a dim light illuminated the lid enough for Stanley to see a carved Tudor rose, ‘simply but deeply incised in outline. On either side of the rose were the carved initials ‘E.R’ and beneath the year ‘1603’. Stanley goes on to describe the lid being decorated with ‘narrow, moulded panelling’ made of ‘fine oak an inch think’, while the base was made of ‘inch elm’. The whole thing was covered in red silk velvet, ‘much of which remained attached to the wood’.

This was Elizabeth’s coffin, her final resting place, laid directly upon the mortal remains of her half-sister, Mary. It is an incredible account – and quite probably unique. It is not the end of our adventures, for I hope to take you exploring the vault in which Henry VII, Elizabeth of York and Edward VI all lie in a future blog. But for the time being, I’d like to thank Queen Victoria and Mr Stanley for bringing us these fantastic tales of the death and burial of Elizabeth I and the secrets hidden in the vaults of Westminster Abbey!

My sincere thanks go to Christine Reynolds, Assistant Keeper of Muniments at Westminster Abbey Library for pointing me towards Stanley’s research of the abbey vaults.

Sources I have found useful in writing this blog:

- Annals of England to 1603, by John Stow

- The History of the Most Renowned and Victorious Princess Elizabeth Late Queen of England, by

- Elizabeth Southwell’s Manuscript Account fo the Death of Queen Elizabeth I, by Catherine Loomis

- The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth by John Nicols

- Reading the Tomb of Elizabeth I by Julia Walker

- Historic Memorials of Westminster Abbey by A. P. Stanley

Fascinating post Sarah I didn’t know the tomb was once coloured. I looked it up of the Westminster Abbey website where is says it was done by the king’s Flemish Serjeant Painter Jan de Critz. We should commission an artist’s impression! On the Abbey audio tour you can hear Elizabeth arguing with her half-sister, Mary 🙂

The image still exists – and I have a very small version but am going to try and eventually get hold of a high res version. Anyway, thanks for dropping by and reading! Much appreciated!

I understand her but why?!! Why did I not get to see her coffin? Whether i like it or not though, I wish her to rest in thou peace.

This is incredibly detailed information! Imagine having the opportunity to squirrel about in that space surrounded by such history! The carving from Elizabeth’s casket is lovely, plain but stately. I have to think she’s enjoy that she’s on top of Mary.

Very interesting well written information. I enjoyed this post and learned a lot. Now I am intrigued to learn more!

Thank you so much for stopping by – and for the feedback. I have found that there is always more to learn and that’s what makes it so interesting!

Thank you for such an informative read!

Could you please explain the discrepancy between the memorial plaque which has Elizabeth’s death dated at 1602 ( although we know it is 1603) & the date on top of the coffin of 1603 according to Arthur Stanley’s sketch? Wouldn’t that have been recorded as 1602 at the time? Hope that’s not a silly question ????

Hi Lea, thanks for your lovely feedback. Umm..I don’t know for sure but here’s a theory off the top of my head: is it something to do with the Tudor new year, which began in March. Was it the 25th? She dies on 24th? Maybe her death was in 1602 but her burial was (as far as the Tudors are concerned), 1603.

Absolutely love this blog post. I was wondering where I can get a hold of Stanleys research to read for myself. I cannot seem to find the book mentioned anywhere.

Hi Caitlin, Look right at the bottom of the blog. It is the last book listed. There is a copy you can view online. There are several volumes, I think, but you can also find the books for sale online. I always try Abebooks for old books.

Fascinating, has whetted my appetite for more.

I’ve read in other places that Elizabeth Southwell isn’t generally considered to be a reliable witness, as she became a Catholic right after Elizabeth’s death and was either pressured to or on her own volition made statements in the interests of making Elizabeth look bad.

It seems someone’s head wouldn’t crack open like that based solely on decomposition and the body had been disemboweled. But then again she was there for a month, so who knows?

Either way, I’ve been reading quite a bit about the Tudors lately and it seems both Elizabeth and Henry VIII were truly remarkable people, not just royal but extremely powerful, both mentally and physically, even when judged by the standards of today.

Remarkable they were – to keep us all transfixed 500 years into the future and I dare say for some time to come!

Love this site I learn something new every time to the page

Thank you!

Just came across your site, love the information and how you paint the story. Can’t wait to pour some more wine and start going from page to page

I LOVE this. Welcome1 and I hope you enjoy them. There are a lot to choose from ????????????

This is one of the greatest explanation I have read so far. Thank you!!!

Thank you so much!

Hello! I have come to find out that I am related to Queen Anne and Queen Elizabeth. Queen Anne is my 2nd cousin 16X removed and Queen Elizabeth is my 3rd cousin 15X removed! All very exciting! I hope to one day visit England and learn so much more! Thanks for the article!

Kelly

Wonderful! Thanks for dropping by. I hope to see you around the Tudorsphere again soon!

Just found your wonderful guide, absolutely spell binding. Queen Elizabeth just passed and I’m guessing that is why you popped up on my Instagram. Love your writing and will read everything you’ve posted. Thank you.

Oh, thank you! I am so glad we found each other and I do hope you enjoy my articles – and podcast and video channel – if that is also of interest! Best wishes, Sarah

Excellent story. With a bit of color. Who knew the body of Eliz. 1 cracked open? Juicy. It is said she was covered in about an inch of lead based makeup on her face. I bet it had something to do with her death. Looking forward to more!

Hi ..have been following you for a while. Always learning so much. Love Tudor history. After reading this article I need clarification from you. I went to England years ago and went to Westminster. Saw Eliz I and Mary’s tomb. Is there nothing in there? Are they empty?

The bodies are in a vault under the floor of Westminster Abbey. So they are there but not inside the memorial / tomb which is above ground.

I want to thank you for your great work, it is a pleasant moment to be able to read your words, which satisfy my anxiety to learn. This publication in particular seems compelling to me, especially the exclusion of the Lancaster coats of arms. Thank you very much for your great effort in this productions. Atte. Juana M. Gestido

You ar welcome!

Thanks – some very interesting detail here. Your readers may also enjoy the Two Mary’s episode from Simon Schamas History of Britain series, which begins with the filing of Elizabeth’s ring from her finger. And for the immediate aftermath of Elizabeth’s death, Leanda de Lisle’s After Elizabeth is a good and authoritative read

I’m hooked. Where do I subscribe?

Hi! Thank you! Just head to my home page https://thetudortravelguide.com and his one of the buttons on the home page, to subscribe and pick up your free mini-guide as a ‘thank you’ for becoming a part of the community.

I’ve always been interested in the royal tombs at Westminster and like you, I was curious about the vaults beneath. Thank you for such an informative article. For your information, I last visited the Abbey in 1992 when I was studying in London (I’m from Malaysia)

I think you are due for another visit! Thanks for leaving your comment. Glad you found it useful. ?

Interesting post. It is interesting that initially she was buried with her grandparents, which I didn’t know before. However there are still a lot of things which puzzle me, and I wondered if you can throw any light on them? First, didn’t she leave any instructions for her own tomb, and if she did so, what were they and why weren’t they followed? Second, I have always wondered why Elizabeth’s body was buried with that of Mary I, it seems such a strange arrangement and is not made any less so by the fact that she was originally buried somewhere else – do you have any theories about that? Third, what were the arrangements for her half sister Mary’s tomb. Mary would have been dead for over 40 years by the time Elizabeth followed her, that means there was ample time for her to have had a tomb of her own, so what happened to it? Sorry if I’m asking too many questions, but will be very interested in the answers.

Hi Irene, Not sure I can answer your questions accurately but I will say what I know or what my theories are. WRT Elizabeth’s tomb. I don’t think Elizabeth liked to contemplate her death too much . She new it was the end of the dynasty. I don’t recall ever reading about plans she made for a tomb. I am not sure she had one. WRT the second point. I jut think it was convenient. The vault was part of the Tudor mausoleum; they were half sisters and there was room in there! As for Mary’s tomb; it seems that often what was constructed after a monarch’s death was in no small part down to the enthusiasm of those left behind. I suspect when Mary died many (Protestants) were glad to see the back of her and were in no mood to glorify her memory.

I don’t know if this has already been asked and answered, but I didn’t know it was usual for monarchs to be disembowelled? I’ve never heard of that before and was wondering if you had any sources I could like at talking about the subject. I thought this was only common for criminals? fascinating read btw!

Removal of the bowels was common / usual practice AFTER death. It was part of the embalming process and prevented the bowels / body exploding under pressure of accumulating gases that occurs post-mortem. Traitors who were hung, drawn and quartered were disembowelled while still alive – yikes!