The Tudor Gallery – The Wonder of the Tudor Age

In this blog we are going to learn all about the Tudor Gallery; who built them and why; what they were used for and how were they decorated. We will learn specifically about some of the finest galleries of the day, including those at Whitehall, Hampton Court and Eltham Palace and next week go deep into exploring one of the finest – and now lost – long galleries of the early Tudor period: The King’s Privy Gallery at Whitehall. So, let’s dive in and go time travelling!

The Tudor Gallery – Types and Purpose

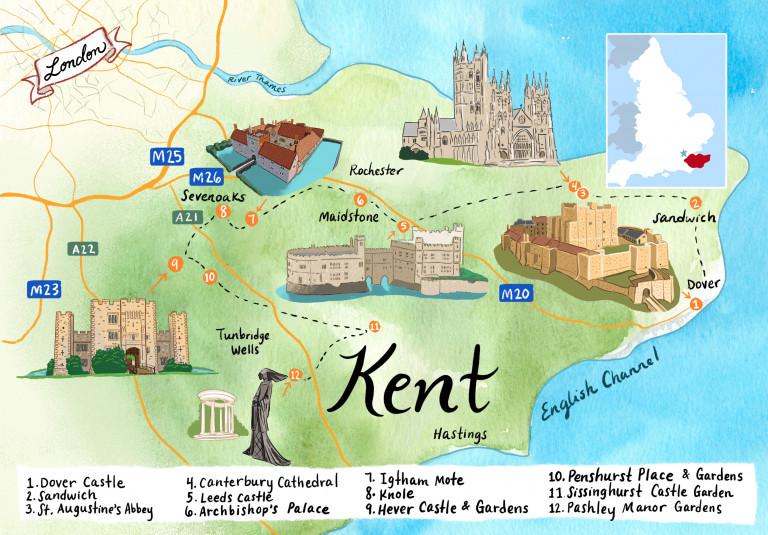

There are two types of Tudor Gallery. The first is the type of gallery which connected one set of rooms, or buildings with another. An example of such a gallery might be the famous ‘Haunted Gallery’ at Hampton Court Palace, which Katherine Howard is said to have run down, trying to reach Henry to plead for her life; the Staircase Gallery at Hever Castle, shown below, or the extensive gallery that ran around the edge of the privy gardens at Richmond Palace, connecting the privy lodgings with the Church of the Observant Friars.

The second type is the well-known ‘long gallery’; as the name suggests, a very long but narrow room, often constructed with a relatively low ceiling to create a sense of intimacy. In aristocratic houses, this type of gallery was usually accessed from the privy apartments but led nowhere in particular. So, it was not a public chamber, but it was used instead for private recreation by the family of the house and their honoured guests. Such was the case with ‘The Queen’s Gallery’ at Whitehall, built originally by Wolsey; or The Long Gallery at The More, in Hertfordshire.

In the case of the former, its purpose was functional, literally a space to connect one chamber, or set of chambers, to another. It was not uncommon, though, for these spaces to be lit by large windows which might have views out over either of the gardens, as was the case with ‘The King’s Gallery’ at Whitehall, or the river, as was the case with Elizabeth I’s ‘Prince’s Gallery’, also at Whitehall Palace.

One of the galleries at Hampton Court Palace, for example, connected the Great Watching Chamber with the Council Chamber. In fact, there are other instances of council chambers being sited off a gallery, such as at The Tower of London and at Whitehall. When this was the case, the gallery also provided a convenient place for courtiers and other invited ‘guests’ to wait until they were summoned inside.

Most galleries, particularly long galleries, were essentially for recreation; large flexible spaces allowing for a range of pastimes; walking, playing musical instruments, gaming or dancing, to name a few. There is even one recorded instance of Henry VIII’s gallery at The More being used for archery practice!

The Tudor Gallery: Construction and Exterior Decoration

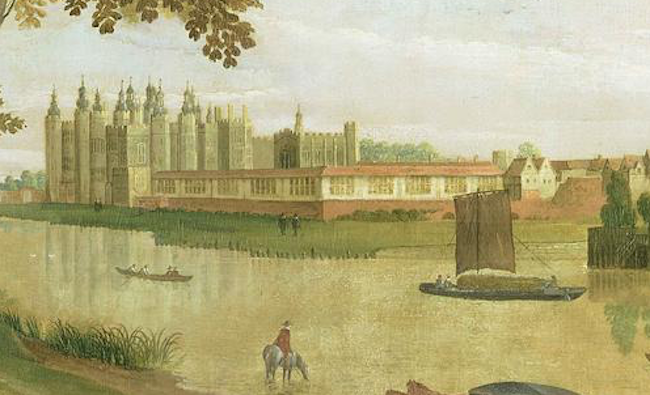

The wherewithal to build fine galleries was the preserve of the very wealthy. According to Simon Thurley, the prototype that all long galleries were to follow was the one built during the 1470s at Eltham Palace by Edward IV, for his queen, Elizabeth Woodville.

During this time, Edward commissioned a new range of queen’s lodgings on the west side of the palace. This range was innovative in that it sported large bay windows, which gave fine views of London. It also had a gallery. This was accessed from the end of the queen’s privy chambers and may have terminated in either a ‘closet or a banqueting house’. It was a design that would be widely copied thereafter by wealthy Tudors as they built their fashionable, new homes.

Indeed, Henry VIII had long galleries constructed at most of his great houses and other wealthy nobles followed suit, including Sir Thomas Boleyn. Shortly after the Boleyn family moved from Blickling to Hever in 1505, Sir Thomas had the Great Hall at Hever reduced in height in order to insert a long gallery above. Of course, Cardinal Wolsey was another great builder of long galleries; in fact, it was Wolsey who inserted the first long galleries at both Hampton Court Palace and York Place.

Most long galleries were two-storey buildings. The ground floor was not uncommonly built like a cloister, open to the outdoor space, but covered, as at Richmond Palace. The first floor was enclosed, and as mentioned above, was usually accessed directly from the secret lodgings of the lord and/or lady of the house. Once again, one of the most tantalising examples of this can be found at Hampton Court Palace.

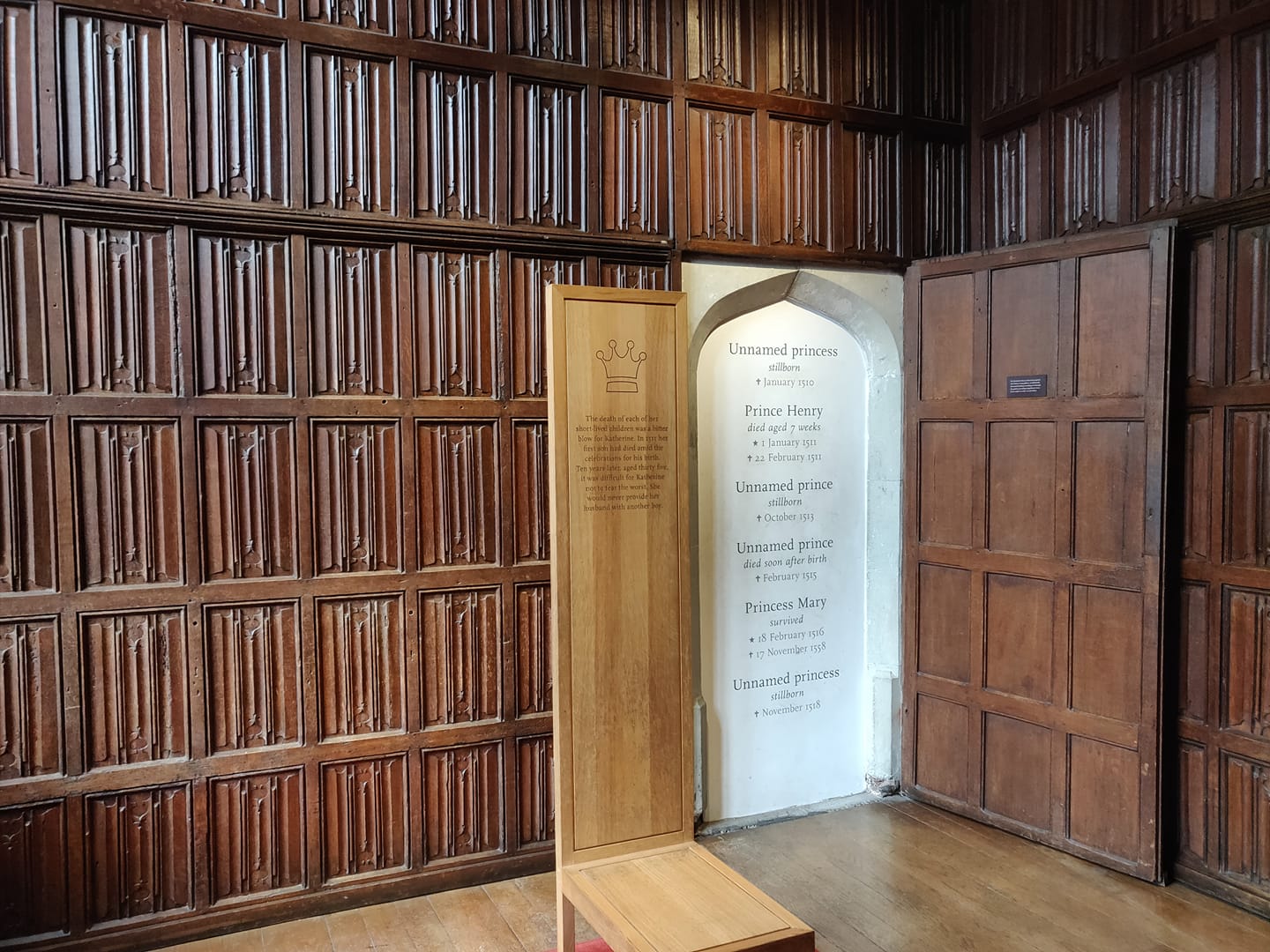

In the last room of Wolsey’s lodgings, there is a bricked-up doorway. Today, the doorway has painted upon it the names of the many children of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon (including miscarriages and stillbirths). Yet, more interestingly, this doorway once opened onto one of the greatest long galleries in England. How I have stood in front of that door, wishing the bricks and mortar would melt away so that I could step over the threshold and rediscover that lost gallery! Alas, I still wait.

However, what happened to the long gallery at Hampton Court when Henry VIII was ‘gifted’ the palace from Cardinal Wolsey is fascinating. Henry added a third floor – another indoor gallery built on top of the first. It must have been a monumental structure! As was the case with all other royal galleries, there was a privy stair leading down from the gallery to the privy garden below, so that the gardens became outdoor extensions of the indoor, private space of the lord or lady, to be used for recreation, private conversation or doing business.

In terms of decoration, galleries were most often panelled in oak. They might also be hung with expensive tapestries. There is a record of Wolsey’s Long Gallery at Whitehall being decorated in this way. Walls were also hung with portraits; at Hampton Court, we know that these portraits were held in place by red ribbon and were covered by little curtains that could be drawn open and closed to protect the pictures when they were not being viewed. Along the length of the gallery, various items of furniture might be found. According to Thurley, these included ‘tables, cupboards, stools – and musical instruments.

The exterior of these galleries also reflected the fashion of the day. Essentially, palaces such as Greenwich and Whitehall were brick-built, but the upper floors were sometimes timber-framed. This allowed the frame to be constructed off-site and assembled quickly once in situ. Antique-work, terracotta roundels and friezes were increasingly popular as Henry VIII’s reign progressed. We know such decoration adorned Henry’s Privy Gallery at Whitehall; it is believed that the building in the background of the painting known as The Family of Henry VIII shows how Whitehall, and probably the Low Gallery, once looked.

The Tudor Gallery: Interior Decoration and The Queen’s Gallery at Whitehall

No account of a gallery would be complete without describing in more detail what you would have seen if you had visited one of Henry VIII’s palaces in the early 1530s. At the heart of the capital, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn were busy planning the enlargement and refurbishment of Wolsey’s York Place: the future Palace of Whitehall. Ultimately, the palace would have several galleries. Here we name but three of the original ones.

In 1531, Henry VIII had Wolsey’s gallery from Esher taken down and used as a basis for constructing what would become ‘The King’s Privy Gallery’ at his showpiece palace of Whitehall. This gallery formed the backbone of the palace and linked the main palace buildings in the east to the leisure complex, and St James’ Park, in the west. There was also ‘The Low Gallery’, a ground floor gallery which ran at right angles to ‘The King’s Privy Gallery’ along the east side of the privy garden. Its interior was adorned with an enormous mural depicting scenes from the king’s coronation. Finally, there was ‘The Queen’s Privy Gallery’. Once again, this had originally been built by the Cardinal before his fall from grace.

This latter gallery was Anne Boleyn’s privy gallery and was sited at first-floor level. Like most of Wolsey’s galleries, it was around 200ft in length and around 20ft wide. The gallery stretched away from the queen’s privy apartments but terminated in a blind end and was purely for recreation. A series of eight large windows gave magnificent views across the river, but also served to flood the chamber with light, whilst three open fireplaces kept any chill at bay. A Venetian count, who visited Whitehall during the period that it was being transformed by Henry and Anne, noted:

“I saw three so-called ‘galleries’, which are long porticos and halls without chambers, with windows on each side looking on gardens and waters, the ceiling being marvellously wrought in stone with gold, and the wainscot of carved wood representing a thousand beautiful figures.”

As this gallery was complete at the time of the count’s visit, it is perhaps ‘The Queen’s Privy Gallery’ that he was describing. What we do know for certain was that it was hung with a magnificent set of twenty-one tapestries, telling the story of Jacob and John; these had been commissioned specifically by Wolsey to adorn the space. Shot through with gold and silver thread, and next to other hangings of cloth of gold and silver, it must have been a truly breath-taking sight. Sir Thomas More is said to have commented to Wolsey that he had a distinct preference for it over the Cardinal’s gallery at Hampton Court.

So now, in your mind’s eye, imagine a space 200ft long and 20ft wide, with fine river views to your left; beneath your feet, you feel the heavy rush matting that covers the floor. All around you, sunlight pours through ornately carved windows and the smell of wood smoke from the three fires spaced along the length of the gallery fills your nostrils.

Look along the length of the room; above you, see the ornately carved, stone ceiling covered in gold; on the walls, see how the decorative carving of around one thousand figures is also picked out in gold, while twenty-one enormous tapestries gleam with gold thread running through them; and all around you, everywhere, on everything are fabrics, upholstery, embroidery and fringing, heavy with more gold thread. Now you have tasted the splendour of a royal, Tudor long gallery!

Next week will we explore one of The Tudor Travel Guide’s favourite lost galleries: Whitehall. The following week, we will be listing our top Tudor galleries, which have all survived stalwartly the test of time. But I need your help; my invitation to you is that this is OUR list. We have our own favourites here at The Tudor Travel Guide, but what about you? Leave your suggestions in the comment box below – and I’ll also be asking the same question throughout the week on social media. Let other people know the top galleries to visit and post now!

To learn more about The Anne of Cleves’ Heraldic Panels, click here. To read more about the rooms in a royal palace read, 9 Key Features of a Tudor Palace. If you want to learn more about Cardinal Wolsey, the great builder of long galleries, please Follow this link to our friends at The Tudor Times.

One Comment