Leez Priory & The Most Notorious Villain in Tudor History

When one of the most commonly cited life achievements of a man is the illegal torture of a defenceless young woman, you know that you must have met one of the most wretchedly cruel villains of Tudor history. However, this man was no shady character of the streets; not a heinous criminal bent on breaking the laws of the land, but a gentleman of the Tudor court who was granted wealth, lands and titles on account of his diligent – and some might say overly enthusiastic – pursuit of serving the blood-soaked whims of the reigning monarch.

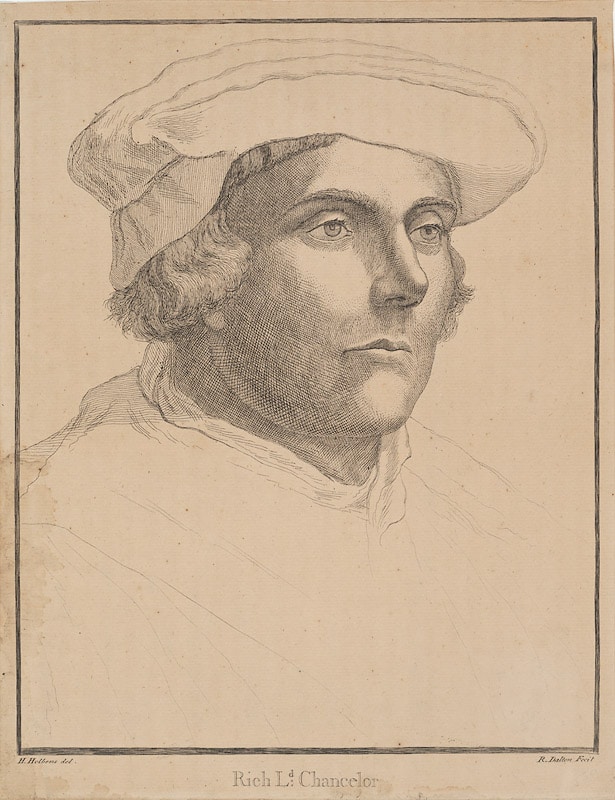

Let me introduce you to Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich, truly one of the most disliked men of his day. In this blog, I will share some of the ‘highlights’ of his extensive court career in which he doggedly appears, time and again, right in the thick of some of the most disturbing events in Tudor history. However, this is the context for our exploration of Rich’s country seat in Essex, Leez Priory, one of the many ‘assets’ Rich acquired due to his central role in the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The Rise and Rise of Richard Rich

I first ‘met’ Richard Rich many years ago when reading about his involvement in the fall of Anne Boleyn. Alongside Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Audley, Rich was tasked with collecting evidence against Anne, which he seems to have done with the same characteristic zeal that we can see repeated with his involvement in the prosecution of other, high profile prisoners of the state including notably, Thomas More, John Fisher, Anne Askew, Catherine Howard and the 3rd Duke of Norfolk. I confess that I developed an instant repulsion to him. It is a distaste that has only grown as I have researched the man for writing this blog. But before we turn to explore his grand country mansion, let us meander a little through his personal history and some of the ‘highlights’ (or ‘lowlights’) of his court career.

Rich was born in Basingstoke, Hampshire in 1496. At the time, the Tudor dynasty was in its infancy, and Henry VII was the reigning monarch. Henry VII’s second son – also called Henry – the first monarch Rich would personally serve, was just five years old. Rich was a self-made man, his intellect securing him a place at Cambridge University before he came to London in 1516 to train as a lawyer at Middle Temple.

By 1528, when Rich was 32 years years old, he began his stellar climb up the greasy pole of Tudor society. Clearly, Richard Rich was ambitious and proactive. He had already put himself forward for election to an office in the City of London, although he failed to secure the appointment. Undaunted, he then wrote to the premier statesman in the land at the time, Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, requesting a position in his household. Although he was not appointed there either, not long after, he secured his first substantive post, in December 1528, as Commissioner for the Peace for Essex and Hertfordshire. Here we see Rich’s connections with the County of Essex being well and truly forged, connections that would remain in place for the rest of his life. We will return to this topic shortly when we explore Leez Priory.

During this period, Rich made friends with the man who would be instrumental in forging his future career at the centre of court life: Thomas Audley. Audley was eight years older than Rich, a groom of the chamber and a member of Wolsey’s household. As Audley’s career took off, so did Rich’s, his progression facilitated by Audley’s rising star. Through the 1530s, the two pop up, repeatedly overseeing the downfall of one unfortunate soul or another.

However, if we are generous to both gentlemen, then it would be to consider the nature of their appointed roles as Henry VIII’s ministers of state. Like Rich, Audley was a lawyer trained at Inner Temple in London and on 26 January 1533, the day after Henry VIII’s secret marriage to Anne Boleyn, he succeeded Thomas More as Lord Chancellor. Not long after, probably with Audley’s help, Rich was appointed as Solicitor General, the premier lawyer in the land. Thus, both were in positions of power, overseeing the judicial and legislative functions of the realm. An integral part of the job descriptions of both men would have required them to dispense the king’s ‘justice’. However, my generosity for Rich ends there for as I have intimated above, it seems that sometimes he went above and beyond the call of duty in pursuing the ‘truth’

We know that Rich was not only involved in the downfall of Anne Boleyn but, as I have also stated, that of Bishop Fisher, Sir Tomas More, Catherine Howard, Anne Askew and Thomas Cromwell. Rich had been one of Cromwell’s proteges but entirely abandoned him in his hour of need and without, it seems, any qualms, happily providing damning testimony against his former friend. As for the 25-year-old Anne Askew, we know that Rich personally turned the wheel on the rack that broke Anne’s body.

Torturing a woman at the time was illegal, and the Constable of the Tower, Sir William Kingston, had refused to do so. Nevertheless, this did not prohibit Rich’s pursuit of a confession that, if given, would have implicated Katherine Parr and some of her ladies in charges of heresy. Bravely, and despite her ordeal, if Anne did know anything of Katherine’s possession of heretical, Protestant texts, she refused to yield to Rich’s bullying and torture.

While we might look back at Rich with distaste, if we were to wonder whether our view is being distorted by the lens of time, we only have to read Sir Thomas More’s damning testimony of Rich’s character to know that even in his day, the man was thoroughly disliked by most of his contemporaries. At his trial, More accused Rich of being a perjurer, an idler and a gambler. Marillac, the French Ambassador, would refer to Rich as a ‘wretched creature’ and, more recently, eminent historian Hugh Trevor- Roper described him as someone ‘of whom nobody has ever spoken a good word’. Quite an achievement!

Around one year later, Richard Rich was appointed to a role that would make his previous participation in such dreadful deads look like child’s play. On 19 April 1536, Rich became the Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations. This office placed Rich as the chief minister overseeing the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the subsequent dispersal of monastic property. In the same breath that called Rich a ‘wretched creature’, Marillac lays the blame squarely at the door of the new chancellor as ‘the first inventor of the destruction of the abbeys and monasteries [and] the general confiscation of church property’. This bloody schism would result in death and misery for hundreds of people, while men like Rich profited enormously from the spoils.

Being Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations meant that Rich had the pick of the crop of newly dissolved monastic properties to add to his property portfolio. Two properties were snatched up by him, thereafter becoming Rich’s main town and country residences. His new townhouse lay just outside London’s city walls at the dissolved Priory of St Bartholomew’s in Smithfield, where his family took up residence in the old prior’s lodgings.

Today, the ancient and entirely glorious church of St Bartholomew the Great still stands, although, thanks to Rich, in a greatly reduced state. Nevertheless, part of the north and south transepts, one range of a cloister, the chancel and Lady Chapel remain and functioned from the time of the Dissolution as the local parish church. St Bartholomew’s has some of the most glorious early Norman architecture of any church in London and is worth visiting. If you wish to find out more about its story, you can purchase ‘Day Three of my Virtual Tour of Tudor London‘ from my Shopify store in which you will explore the Tudor history of the church with your Tudor guide.

The Building of Leez Priory

May 1536 was a busy month for Richard Rich. Just as he was finishing up with the wholesale destruction of Anne Boleyn and the Boleyn faction, on 27 May, Rich granted himself the recently dissolved priory at Little Leighs, in Essex. This monastic institution had been founded some 300 years earlier by an order of Austin Canons. While Rich required a London base from which to transact court business, clearly he was fond of Essex, and Leighs Priory would, after that, become his principal country seat.

His new home at Leighs – which Rich later renamed ‘Leez Priory’, was situated about 40 miles north-east of his London townhouse in Smithfield. It lay amidst the picturesque surroundings of the Ter Valley, with the River Ter running just to the north of the priory. At the same time, he also acquired several other properties that had belonged to the priory, including the manors of Great and Little Leighs and two manors in Felsted.

Rich needed to create a stunning landscape to set off the grand Tudor mansion he began building shortly after the priory came into his possession. To create this landscape, Rich acquired additional land to create two new parks, all stocked with deer to provide for the noblest of Tudor pastimes: hunting. One of the parks, known as Pond Park, consisted of 12 lakes that ran along the course of the River Ter, stretching over a distance of 2.5km. These have been called ‘fishpools’ and ‘millponds’ over time. They were, no doubt, a source of food for the kitchen, but the scale of the artificial undertaking to create the lakes points to Rich’s primary aim; to create an impressive landscape that spoke of his power and wealth.

Whatever grand entrance to Leez Priory existed back in the sixteenth century has long since been lost. According to the Essex Garden Trust, who has written a lovely paper about the parkland at Leez Priory, ‘The original grand approach to the house was from Crow Gate on the Chelmsford/Dunmow road, and it can still be followed on a bridleway named the Causeway. It curves down through Littley Park to cross the floor of the valley of the River Chelmer…The route curves up to and beyond the park lodge to reach a large flat plateau. Here it runs dead straight on a low embankment. At the northern edge of the plateau, the towers and roofs of Leez Priory, and the chain of lakes in Pond Park in the valley of the River Ter, would have come dramatically into view’. And there is Rich’s intention; to make a statement and impress any visitors to Leez Priory.

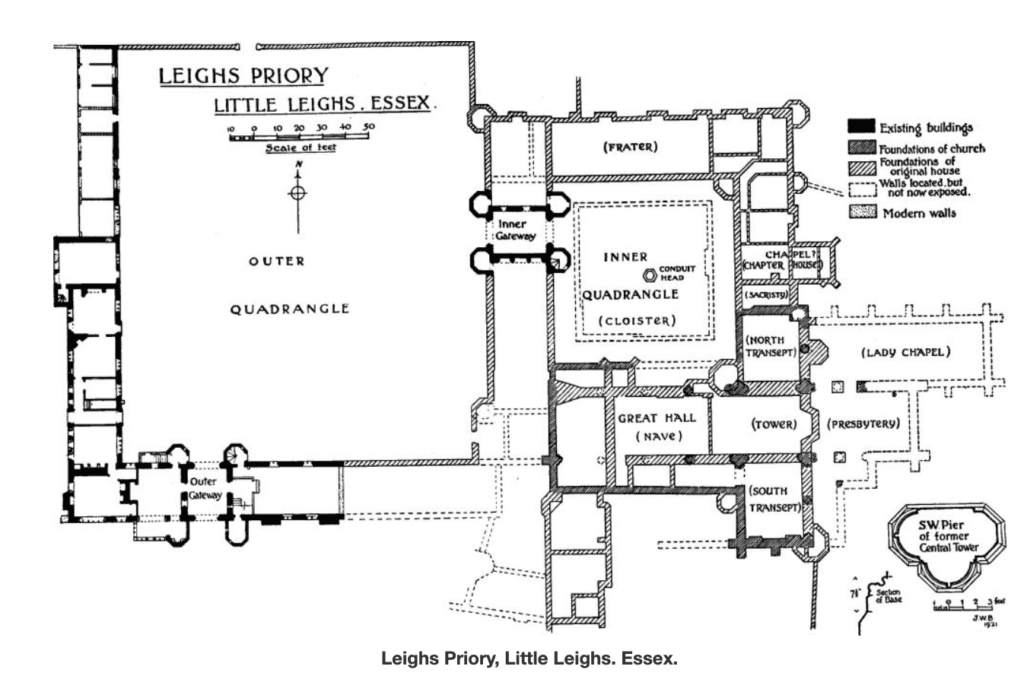

So what about the house itself? What did Rich do with the pre-existing priory and what did the Tudor manor look like? To answer the first question, like many dissolved properties, Rich retained part of the priory church and its buildings, much as he did at St Bartholomew in London. The plan above shows the mansion Rich built for himself – as well as highlighting those parts of the original priory buildings that were lost. So, we can see that the presbytery and Lady Chapel were taken down, but much of the priory was incorporated into the new building. Thus, the nave of the church became the new great hall.

According to British History Online, the foundations remain, showing us that the hall was accessed via a porch and had an oriel window projecting into the inner courtyard. The north and south transepts and the central tower became part of the south-east corner of the inner residential lodgings. The old chapter house was probably converted to a chapel in the same eastern range and enlarged.

Since we are speaking of the chapel, on the face of it, it is difficult to decipher Rich’s true religious inclinations; he launched himself with alacrity into the Dissolution of the Catholic Monasteries yet was embroiled in Bishop Bonner’s pursuit of the eradication of Protestants in London in the 1540s. He helped bring down the conservative 3rd Duke of Norfolk, yet assented to the Proclamation of Lady Jane Grey as Queen, before being one of the first to embrace the new Marian reign under which he would supervise the burning of heretics in his adopted home county of Essex. However, on balance, most historians seem to agree that Rich was a Conservative Catholic at heart, his religious convictions shifting with the prevailing whims of the reigning monarch.

This eastern range, where the chapel was sited, was most likely the privy range occupied by the family, as it looked out over the gardens. This garden was rectangular, walled and with octagonal summer houses at each far eastern angle, while a bridge crossed over the River Ter to the north of the house.

At the house, octagonal turrets decorated the outer angles of the ranges surrounding the inner courtyard and probably also in the inner angles. The remainder of the cloisters formed the rest of the north and west ranges. This inner courtyard was accessed by a gorgeous, turreted inner gateway, resplendent with all the features one would hope to see from the architecture of the day: red brick and diapering; an entrance framed by a typical Tudor arch; tall, mullioned windows and octagonal side towers. Thankfully, this inner gateway still stands and can be enjoyed in all it’s glory (see the image below).

Turning back to our plan, we can see a large outer court to the left of the image. This was bounded on the east by the west range of the inner cloister, to the north, south and west by new ranges, which Rich commissioned after acquiring the priory. Undoubtedly, these ranges contained either offices serving the functioning of the house and/or additional accommodation for guests. The entry point to this base court was via an outer gateway in the south-west corner of the courtyard. Once again, we are lucky in that this outer gateway survives, as do more than half of the west and south ranges. The remainder of these lost ranges, and the northern range, have been replaced by low walls, which according to BHO ‘incorporates the base of the original ranges’.

The End of Richard Rich

Whatever one might say about Rich, his morals and career, he was undoubtedly a survivor at a time when wealth, status and power so easily garnered enemies that could result in swift personal annihilation. After the death of Henry VIII in 1547, he went on to win the support of every subsequent Tudor monarch that followed, being made 1st Baron Rich under Edward VI, while persecuting and burning heretics under Mary I. He served Elizabeth I, and was styled as ‘councillor’. However, he never officially sat on the Queen’s Privy Council. Perhaps she remembered his role in her mother’s downfall.

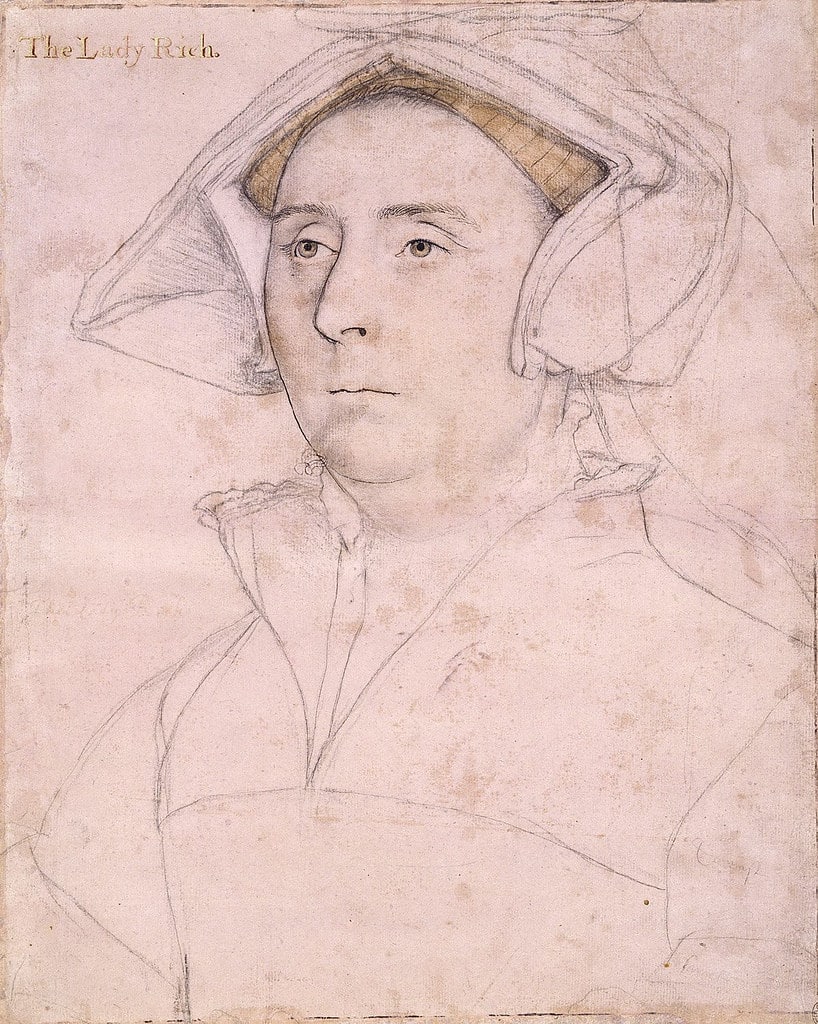

During his life, Rich had 11 children by his wife, Elizabeth Jenks (see above), who he married in 1535. He also had at least one illegitimate son; clearly, he was as active in his private life as in his public one! Yet there seems little justice in this world, as Rich lived to die in his bed at Rochford Hall in Essex, the one-time home of a family he had once helped destroy – the Boleyns. The date of his death was 12 June 1567. He was 70 years old.

However, Rich was not buried at Rochford parish church but carried the 30 miles or so north back to his estates surrounding Leez Priory. In this last act, we see Richard Rich’s love for his adopted home county, not too far from where he had first been elected to a substantive office as Commissioner of the Peace. He was finally laid to rest in Holy Cross Church, Felsted. A fine tomb survives that shows the elder statesman dress in the garb of Lord Chancellor, a position he held under the reign of Edward VI. The figure is recumbent, resting his elbow upon a pillow, the knuckles of his left hand supporting his chin, his right clutching a book. From lifeless eyes, Rich stares out coldly at any passer-by who might care to pause and reflect upon his life, a life that saw so much destruction and suffering inflicted on those who were unfortunate to cross the path of one of the most notorious villains of Tudor history.

In the Footsteps of Richard Rich: It is still possible to visit several sites associated with Richard Rich. Leez Priory is run as a wedding venue, but the grounds are open to the public. The remains of the Church of St Bartholomew the Great still stand in Smithfield and, of course, you can visit Rich’s tomb in Felsted church.

Useful Links and Sources

Little Leighs, British History Online

Leez Priory – Essex Gardens Trust

Richard Rich – Spartus Educational –

RICH, Richard (1496/97-1567), of West Smithfield, Mdx., Rochford and Leighs, Essex.The History of Parliament.

Richard Rich MP (abt. 1496 – 1567), Wikitree

Enjoyed this story do very much. Thank you for doing it.

Thank you! Much appreciated.

I think his true religion was Psychopath. He believed in anything that would allow him to seize property and torture people.

Yay …I found out he his a grandfather of mine .

I couldn’t agree more, horrid little man.

Thank you Sarah. A really interesting and well illustrated story.

Thanks so much, Barry!

I live very near Leez Priory. Wanted to get married there but was far too expensive for us.

Really interesting. I have read about him for some time-and still wonder why everyone ‘knows’ about Cromwell, but relatively few about Rich. I also think he had only one religion-the religion of Richard Rich, but that is a personal view.

Hi Jane, Absolutely – I couldn’t agree more – on both counts. I find Cromwell’s men fascinating and will be writing about Ralph Sadler next.

Will look forward to your writing on Ralph Sadler. How about Gregory Cromwell?

Both are on my list. So keep an eye out! ????

Thank you for featuring Leez Priory. It was also favored by his grandson’s wife, Penelope Devereux Rich, during their marriage. They were not happily married, but she favored Leez as a retreat and spent quite a bit of time there with her children (those fathered by Robert Rich and her lover Charles Blount). A couple of other interesting parallels with her grandfather-in-law: Penelope was the great-granddaughter of Mary Boleyn, and she was interested in aspects of the Catholic faith or at least sympathized with those who were practicing Catholicism. She definitely lived life on the edge of danger.

Hi Laurie, Thanks for the little bit of extra info. Nice one! ????????????

I did too!!! He is like my 13 grandfather of all the people— he had a son out of wedlock named Richard who had a daughter named Ann her son Nathaniel Brown is who I am descended from