Tudor Day Trips From London: Canterbury

While London certainly has its fair share of sixteenth-century hotspots, many Tudor treasures lie beyond the city. Venturing off the Tudor trail means discovering lesser-known historic sites often set amidst stunning countryside.

About sixty miles southeast of London, Canterbury lies in the heart of the picturesque county of Kent. The seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the highest-ranking member of the clergy, Canterbury was an important medieval city. Wandering its cobbled streets and ancient walls, a considerable slice of medieval and Tudor Canterbury can still be seen today.

Canterbury: Essential Travel Information

Travel:

- By Train from London Bridge or London Victoria (Direct trains once an hour) to Canterbury.

- By Car, around 2 hours from central London.

Journey Time: 1h 30 mins (direct)

Distance from Station to City Centre: 10 mins walk

Key Locations:

- The Cathedral Quarter

- Canterbury Cathedral

- St Augustine’s Abbey and the Fyndon Gate

- The City Walls

Introduction to Canterbury City

Kent, according to John Leland: ‘Let this be the first chapter of the book…The King himself was born in Kent. Kent is the key of all England.’

Canterbury became established as the place where Christianity was re-established in southern England when the Pope sent St Augustine to England in 597 AD. Augustine established a monastery, whose ruins can still be seen today, and founded the first iteration of Canterbury Cathedral on the spot where the present medieval building now stands.

Certain parts of Canterbury are UNESCO World Heritage sites, including St Martin’s Church (the oldest existing parish church in the English-speaking world – circa 6th century), St Augustine’s Abbey and the Cathedral.

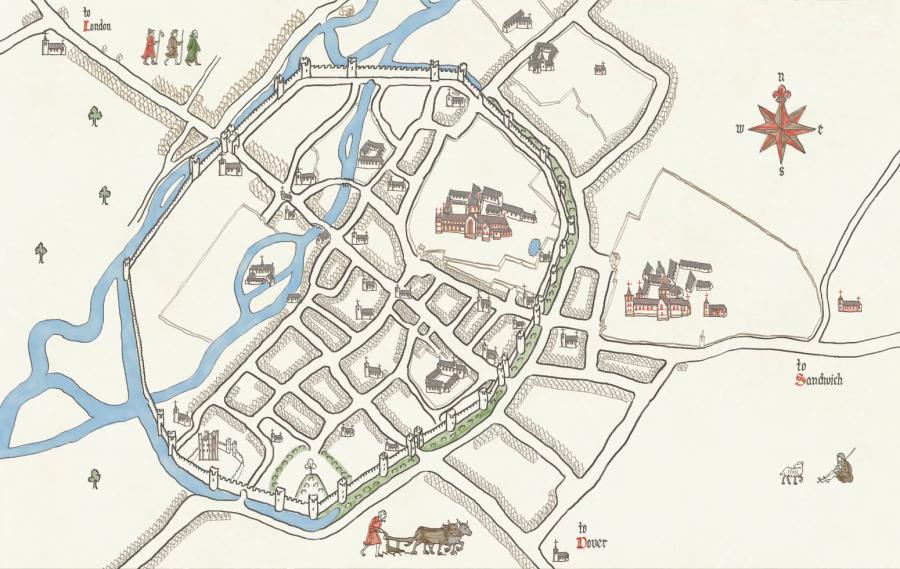

Map of Medieval Canterbury. Image courtesy of thebecketstory.org.uk.

Origin:

As mentioned above, Canterbury grew in importance because St Augustine was sent from Rome to convert the local Saxon population to Christianity, where he founded a monastery adjacent to the city, just outside its Roman walls. Later, following the murder and subsequent beatification of Thomas a Beckett, who was murdered ‘on the orders’ of Henry II in the Cathedral, Canterbury became a popular pilgrimage site, adding to the city’s prestige.

Canterbury is associated with no less than nine saints:

- Saint Augustine of Canterbury

- Saint Anselm of Canterbury

- Saint Thomas Becket

- Saint Mellitus

- Saint Theodore of Tarsus

- Saint Dunstan

- Saint Adrian of Canterbury

- Saint Alphege

- Saint Æthelberht of Kent

Canterbury c.1450. Image courtesy of thebecketstory.org.uk.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, when Canterbury was called Durovernum Cantiacorum, the city was walled. Although these had fallen into disrepair by the early medieval period, they were rebuilt between 1378 and 1402.

Over half the original circuit survives, and alongside the likes of the northern cities of York and Chester, they are some of the most magnificent in Britain. Most of the walls that can be seen today are medieval in origin, and of the original 24 medieval towers along the walls, 17 remain intact, and one entranceway into the city, the Westgate, also survives.

It was via the Westgate that most pilgrims would arrive from London. The High Street, which linked the Westgate with the cathedral precinct, had the wealthiest shops, selling souvenirs and providing rest and refreshments for travellers. You can follow this route today as you wander from Westgate train station to the Cathedral.

Westgate, Canterbury. DeFacto, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tudor History:

1520 saw the grand reception at the Archbishop’s Palace for the Holy Roman Emporer, Charles V. This was held over two days, just ahead of The Field of Cloth of Gold. Henry and the court were on the way to Calais. Positioned on the London-Dover road, Canterbury was a natural meeting point for the two monarchs.

Charles landed at Dover and was greeted by Wolsey, who rode out on a boat to greet Charles. After staying at Dover Castle and being greeted by Henry there, the pair rode back to Canterbury the following day to be received honourably by the city in the usual fashion.

Charles met his aunt Katherine (of Aragon), who was waiting for him at the Archbishop’s Palace. Piety and pageantry followed, with great pomp and ceremony centred around the Cathedral precinct. To read more details about this great Tudor ‘party, you can check out my two-part blog here and here.

In 1532, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn lodged at Canterbury on the way to and from the historic trip to Calais, in which Anne was presented to the French court as Queen-in-Waiting, having only recently been made Marquess of Pembroke at Windsor Castle on 1 September of the same year.

They stayed at Sir John Feneux’s house in the city. At one point, he had been Henry’s Lord Chief Justice. So, he was not only an influential man of some status in the city but also to the realm. As a result, he likely owned a property of some luxury, indeed suitable enough to house the King. (We should note that the natural choice for their lodgings in Canterbury would have been the Archbishop’s Palace. However, at the time, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham) was none-too-pleased with Henry for setting aside Katherine of Aragon and, therefore, may not have extended an invitation for the royal couple to stay there.)

A recent discussion with a historian of Medieval / Tudor Canterbury has indicated to me exactly where John Feneux’s house once was in the city, sitting on the High Street, adjacent to one of the tributaries of the River Great Stour as it flowed through the town.

The Cathedral Quarter

This area is the oldest part of the city. You will find narrow medieval streets, alongside many shops, bars and restaurants to enjoy. Why not enter via Westgate and wander down the High Street before turning left into Mercery Lane, a tiny medieval street that leads down to Christchurch Gate?

The gate was originally built to celebrate the marriage of Arthur, Prince of Wales, to Katherine of Aragon in 1502. However, it was not finished until 1520, probably for the Field of Cloth of Gold celebrations noted above, and was/is the main entrance to the cathedral precinct.

It has very recently been renovated and so is in exceptional condition.

Canterbury Centre; The Cathedral Gate, Tony Hisgett, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Canterbury Cathedral

Founded in 597 by St Augustine as a benedictine monastic community, the cathedral was completely rebuilt between 1070 and 1077. The east end was greatly enlarged at the beginning of the twelfth century to accommodate pilgrims who flocked to Canterbury to visit the shrine of St Thomas a Becket.

The Norman nave and transepts survived until the late fourteenth century, when they were demolished to make way for the present structures. These were built in the Gothic style. We should note that the Archbishop of Canterbury, then as now, was the premier prelate in England and, therefore, the most important Archepiscopal See in the country.

Canterbury Cathedral exterior, Hans Musil, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons;

Canterbury Cathedral interior;

Martyrdom, Canterbury Cathedral, David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons;

Royal window; The Trinity Chapel, Canterbury Cathedral, Photo: Laurence-OP, licensed-under Creative Commons.

Visiting Today

By far, the most significant and interesting Tudor event that I know of that happened at Canterbury was the meeting of five monarchs at the Cathedral (Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon, Charles V, Queen Germain de Foix and Mary Tudor, Queen of France). I encourage you to read my two blogs before your visit and then walk up the nave to the chancel, where, no doubt, in positions of honour, these monarchs heard the Mass being said by Archbishop Warham. Let your imagination run wild! However, here is a snippet:

Having entered by the principal door, the Sovereigns walked over a carpet of purple velvet to a kneeling desk for two persons, in the English fashion, covered with gold brocade and furnished with two cushions to correspond. There they knelt, the Emperor on the right hand, the King on the left; and the Archbishop of Canterbury, standing before them in his episcopal robes and mitred, presented the cross for them to kiss, commencing with the Emperor and then saluting them with the censer and incense; finally, he sprinkled them with holy water, always commencing with the Emperor. Their Majesties then rose and were conducted under a canopy of cloth of gold to the high altar, where, in like manner, a kneeling desk had been prepared with cushions of cloth of gold and the ledge covered with crimson velvet. There they again knelt, and the Archbishop presented them with the wood of the holy cross to kiss and then commenced the hymn, “Veni Creator Spiritus” which was suited both to the day, Whit Sunday and also to the conference between the two Sovereigns, united by spiritual love and goodwill for the benefit of Christendom.’

Sadly, once adjacent to the cathedral’s west end, the archbishops’ palace is all but gone. Some fragments are incorporated into later buildings.

Henry IV and his Queen Consort, Joan of Navarre; Shrine of Thomas A Beckett; Tomb of Edward, the Black Prince.

Other significant but non-Tudor favourites are:

- The Trinity Chapel and the Corona Chapel, where the shrine of St Thomas and his skull were located, respectively, before the Dissolution.

- The place in which Thomas a Beckett was martyred is an area now called ‘the martyrdom’ and is conspicuously marked. You cannot miss it.

- The crypt where Thomas’ body was first buried until the bones were moved to his newly-built shrine in the Trinity Chapel in the thirteenth century.

- The tomb of Henry IV and his Queen Consort, Joan of Navarre: the only English King buried at Canterbury because of his devotion to the cult of St. Thomas.

- The fabulous tomb of Edward, the Black Prince. He was the eldest son of Edward III and was, therefore, Prince of Wales. However, he died before his father, leaving his son to become King Richard II. His surcoat, helmet, shield, and gauntlets are still preserved. His epitaph reads:

‘Such as thou art, sometime was I.

Such as I am, such shalt thou be.

I thought little on th’our of Death

So long as I enjoyed breath.

On earth I had great riches

Land, houses, great treasure, horses, money and gold.

But now a wretched captive am I,

Deep in the ground, lo here I lie.

My beauty great, is all quite gone,

My flesh is wasted to the bone”

St Augustine’s Abbey and the Fyndon Gate

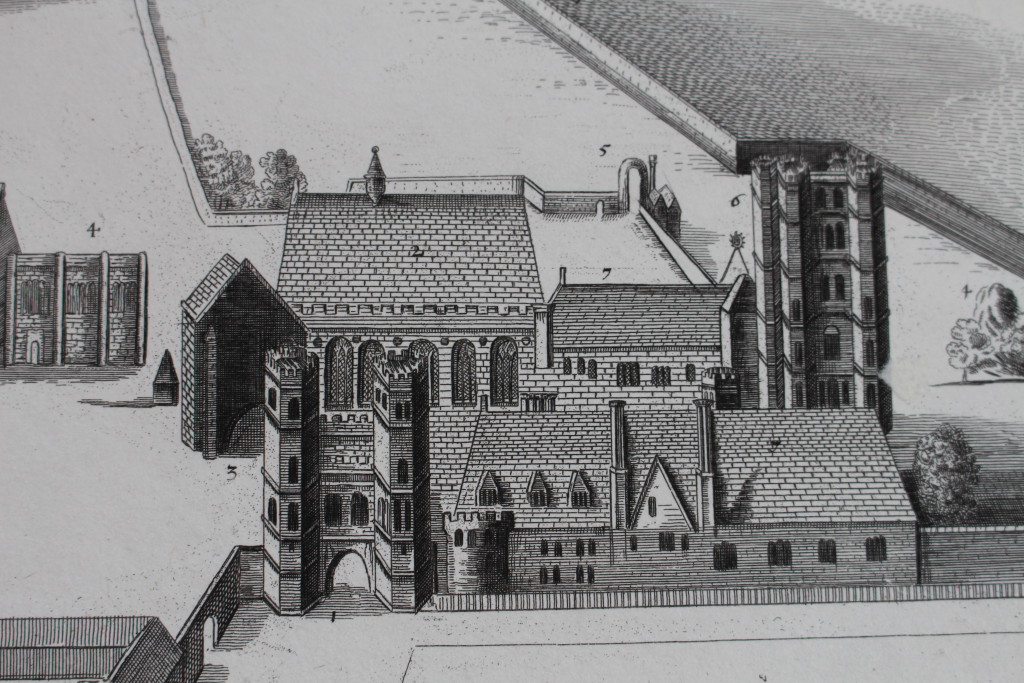

The Abbey was founded by St Augustine after his consecration as the first Archbishop of Canterbury in 597.

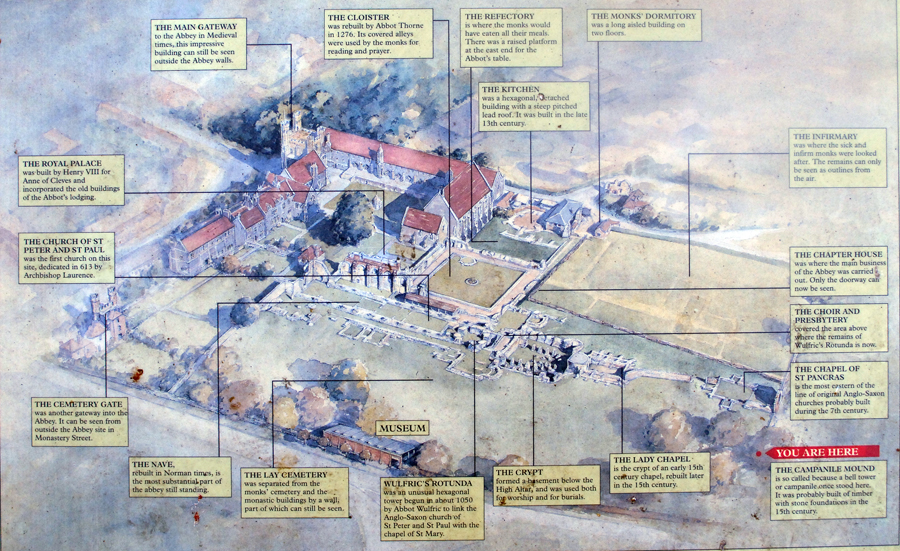

The abbey lay just outside the city walls and Burgate, east of the city. A recreation of the one-time appearance of the abbey demonstrates its scale and importance: it was the epicentre of Christianity in England. The body of St Augustine himself, along with several generations of Saxon archbishops, were laid to rest in the abbey church.

After about 900 years of Christian worship, Henry VIII, aided by Thomas Cromwell and his men, brought that to an abrupt halt on 30 July 1538, when the abbey was dissolved, and the church and many of the associated buildings were torn down.

Fydon Gate today; the damaged Fydon Gate; Plan of St Augustine’s Abbey; The King’s Manor, St Augustine’s.

The Tudor History Of St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury

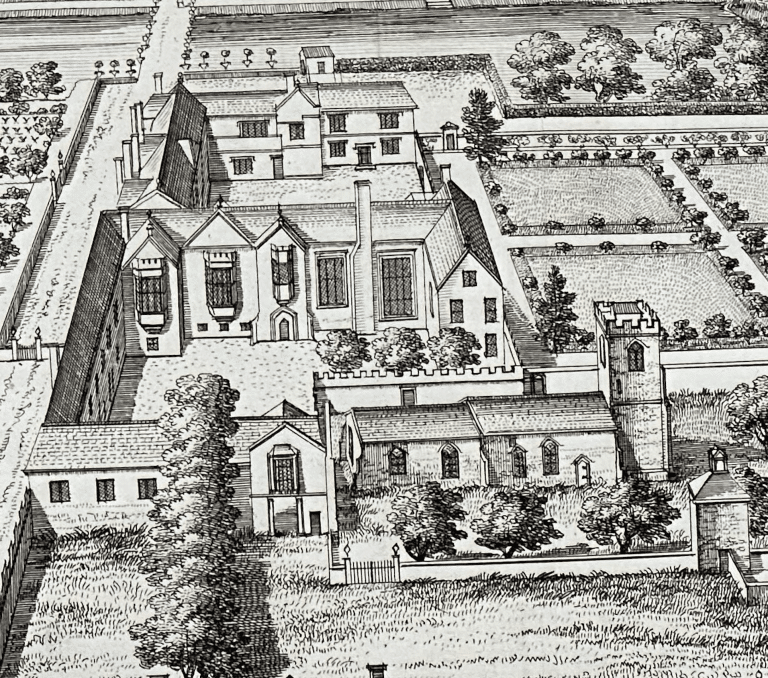

The abbey’s end is the beginning of its Tudor story. Henry had some of the claustral buildings refurbished and rebranded as the ‘King’s Manor’ and redeveloped an entirely new range of buildings for the Queen’s side. The work was to be completed in time for the arrival of Anne of Cleves in England. She was, of course, being received on her way to marry the King.

Work began on 5 October, the day before the marriage treaty was signed. Three hundred fifty workmen were recruited to finish the work on time. There are copious notes of the work undertaken to redevelop this new range of lodgings under the lead of the Surveyor of the King’s Works, James Needham. So great was the task, and so little the time available, that the workforce toiled in shifts, working through the night by candlelight and with braziers burning constantly to dry out the plasterwork.

The new queen’s lodgings consisted of two ranges; one contained the outer/public facing ranges, situated directly across the courtyard from the King’s range (which were the refurbished Abbot’s lodgings). Running perpendicular to the aforementioned range, the second contained her privy lodgings. These joined the King’s at the old abbot’s chapel. This became known as ‘The Chapel Royal’.

The following is an extract from In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII describing the Queen’s new lodgings…

‘The new queen’s lodgings consisted of two ranges. The first range contained the principal privy chambers, which ran perpendicular to the king’s in an east–west direction and were sited at first-floor level. Both these sides joined each other at the old abbot’s chapel, positioned directly north of the defunct abbey church (which was demolished 1541–53). This would henceforth be known as the Chapel Royal. Adjacent to this chapel was a ‘little chamber’ that appears to have separated the king and queen’s bedchambers. The second range contained the queen’s public chambers (these being the outer great chamber and the great chamber). Running on a north–south axis, parallel to the king’s side, this second range joined the main gatehouse in the north to the queen’s privy apartments in the south. It formed the final wing of the new complex, all of which fronted on to the renamed ‘palace courtyard’. In all, Anne’s new lodgings included an outer great chamber, a great chamber, a watching chamber, a presence chamber (which probably doubled up as a dining chamber), privy chamber, bedchamber, closet and chapel. According to the History of the King’s Works, the main building was a timber-framed structure 13 feet 6 inches high standing on brick basement walls … apart from the basement walls, the principal features built in brick were five chimney stacks, some gable ends and two jakes. The fireplaces were provided with … mantles of stone. The roofs were tiled …The buildings were finished inside and out by plasterers who lathed and ceiled the roofs [and] pargetted the internal partitions.

The account of the plasterers ‘whitening the outside of the hall’ on the King’s side, along with painting the King’s lodgings with yellow ochre and his privy lodgings with ‘pencilled’ red ochre, conjures up images of Whitehall Palace. This part-timber, part-brick building had been similarly decorated several years earlier in the height of Renaissance fashion.

Finally, Anne was to be honoured with the placement of her badges alongside the King’s in the new windows, glazed by the King’s master glazier, Galyon Hone. At the same time, four representations of her arms were painted by John Hethe of London, ‘one in the waiting chamber and ii [2] in her chamber of presence’, the final one being executed in oil and set over the half-pace stair going up to the Queen’s lodging. Perhaps it was the first time Anne had seen her badge so proudly displayed on English soil.

In a letter written to Lady Lisle, we hear how Anne entered her ‘grett chamber’ upon arrival at the abbey. Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and Sir Thomas Cheney go on to say in their joint missive, written to Cromwell from the abbey that very evening, that in that chamber ‘were 40 or 50 gentlewomen [who waited] in velvet bonnets to see her, all which she took very joyously, and was so glad to see the King’s subjects resorting so lovingly to her, that she forgot all the foul weather and was very merry at supper’. ‘

Canterbury City Walls

You can walk a section of the city walls. Sadly, it is right next to a very busy road! The best city walls I have encountered so far are in York, and I highly recommend them to you if you want to enjoy an experience of ‘walking the walls’.

One part of the walk gives a view of all that is left of Canterbury’s medieval castle. This consists simply of an earthen mound located in Dane John Gardens. However, this mound was remodelled from the original one that formed the motte of an eleventh-century castle. The castle was later abandoned, and a second iteration was constructed nearby. The gardens surrounding the mound were created in the late eighteenth century to incorporate the mound and part of the city walls.

Useful Links

For visitor information on the places mentioned in this blog, please use the links below:

Some of the locations in this blog are explored in my book, In The Footsteps Of The Six Wives Of Henry VIII – you can purchase a copy here.