Thomas Wolsey’s Tudor Ipswich

Note: This is a show notes page accompanying my on-location podcast in Ipswich, recorded in the spring of 2023.

To commemorate Cardinal Thomas Wolsey’s death on 30 November 1530, this month’s episode of The Tudor History & Travel Show takes us to a town deeply connected to Wolsey’s early years: Ipswich in Suffolk. We’ll unpack Wolsey’s story from the place of his birth, c. 1470-3, to the college he founded in the town in 1528.

A Brief History of Thomas Wolsey

Wolsey was born and raised in Ipswich and is fondly known as ‘Ipswich’s Greatest Son’. Despite his humble beginnings, he displayed exceptional intellect and a talent for organisation from an early age. He matriculated from Magdalen College School in Oxford at a young age and eventually entered the service of Henry VII as one of his chaplains. This was his first taste of the royal court and a career of service that would span over a decade. Through his prodigious skills, the butcher’s son rose through the ranks of the church and state to become one of the most influential figures in the court of King Henry VIII as England’s Lord Chancellor.

During his time at court, Wolsey amassed unprecedented wealth and authority. Arguably, his influence surpassed any previous Crown servant in English history. Through his diligence and unswerving application to serving his master, Thomas Wolsey earned Henry’s unconditional trust. As the Pope’s legate in England, he also wielded preeminence in the English church, even over the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

However, Thomas Wolsey met his downfall over his inability to secure the annulment of King Henry VIII’s marriage from his first wife, Katherine of Aragon. This stalemate dragged on for six years. It became known throughout the court as ‘The King’s Great Matter’ and garnered enemies, namely in the form of the Dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, who temporarily allied themselves with the King’s wife-to-be, Anne Boleyn intending to bring down the Cardinal.

While Anne had long smarted from Wolsey’s intervention to prevent her earlier marriage to Henry Percy, the future Earl of Northumberland, the nobility resented the Cardinal for his presumption, arrogance and influence with the King. They considered Wolsey a ‘base born’ man who had reached beyond his station in life. The Cardinal’s failure to secure an annulment allowed Wolsey’s enemies to turn the King against his first minister and erstwhile friend.

After being charged with praemunire and forfeiting virtually all his offices and goods to the King, Wolsey retired to his diocese at York. However, he was arrested for High Treason three days before his intended enthronement at York Minster. During his journey to London, Thomas Wolsey was taken ill and died at Leicester Abbey. He was 57.

In this podcast, I’m joined by Phil Roberts, author, historian, and expert on the life of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. Phil takes me on a tour of Ipswich, reconstructing its Tudor streets and transporting us back to how it looked during the sixteenth century.

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Before we started the tour, I asked Phil a question I had been pondering for some time. His response has been summarised below:

Sarah: What do you think you learned about Thomas Wolsey that has really changed for you, or what are the biggest misconceptions that you would love to see put right?

Phil: One thing that comes to mind is his ‘softness’ with the Lutherans. Hugh Latimer was beginning to preach the Lutheran gospel in England and was a priest in the diocese of Ely, not far from Cambridgeshire. At the time, he was arguing with his bishop, Bishop West. Wolsey heard of this disagreement and wanted to interview Hugh Latimer, which he did. At the end of the interview, Wolsey gave Latimer a licence to continue his preaching, which to me is pretty remarkable! I mean, Wolsey never burnt any heretics as Thomas Moore certainly did – although he burnt some of Martin Luther’s books outside St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Sarah: But he didn’t burn any people?

Phil: No, not at all. No. He was very lenient towards this new movement. And who knows? He would have probably spoken to Thomas Cromwell about it, who was his loyal servant. As we know, Thomas Cromwell was one of these new Evangelists, as they were called then. So, I like the fact that Wolsey took on board differing views. He wasn’t judgmental and as conservative as we might think!

Thomas Wolsey’s Tudor Ipswich

All images in this gallery are the author’s own unless otherwise stated.

Here’s a summary of some places associated with Wolsey’s Tudor Ipswich. The map has a pin for each of the locations we visit. Tune in to the podcast to find out more.

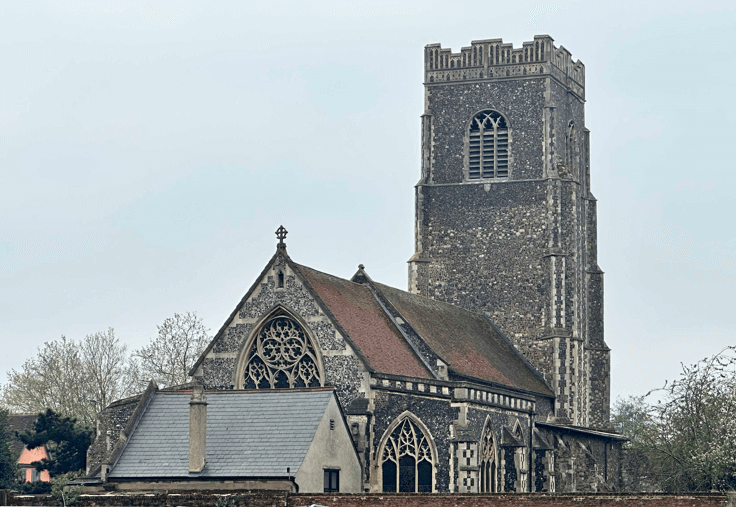

St Clement’s Church

One of twelve medieval churches in the town, St Clement’s Church was known to many as the Sailors’ Church’; St Clement being the patron saint of sailors. It stood close to the waterfront and Wolsey’s College at Ipswich. It certainly would have been a familiar sight to the young Thomas Wolsey.

St Clement’s Church, Ipswich.

Black Horse Pub

The Black Horse is regarded as the likely location of Thomas Wolsey’s birth circa 1470. Originally a merchant’s house, it is thought that the original medieval building dates back to when the Wolsey family were in residence. However, it is unclear how much of that original house survives and is incorporated into the fabric of the current building.

Wolsey’s father, Robert, was an innkeeper and subsequently a butcher. It is possible that they ran both businesses from the building that once stood on the site of the current Black Horse pub.

The Black Horse Pub, Ipswich. Scroll to see photos of Sarah and Phil outside the pub.

St Mary At The Elms, Ipswich

St Mary at the Elms is likely the place of Wolsey’s baptism, with the chancel and the altar remaining unchanged from the sixteenth century. The church is located literally just around the corner from the likely place of Wolsey’s birth (see The Black Horse above), and its main door is one of the oldest in the country. You can still get up close and run your fingers across the gnarled timber from which it is made or admire the font, which may have been used to baptise the infant, Thomas.

Both these locations were close to one of the most important Marian shrines in the country, known as ‘The Shrine to Our Lady of Grace at Ipswich’. It was an important pilgrimage place; as a child, Thomas would have seen many thousands of pilgrims flocking to benefit from the miracles attributed to the shrine.

St Mary at the Elms, Ipswich, by Heather Weir, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Close-ups of the church door, font and interior – author’s own.

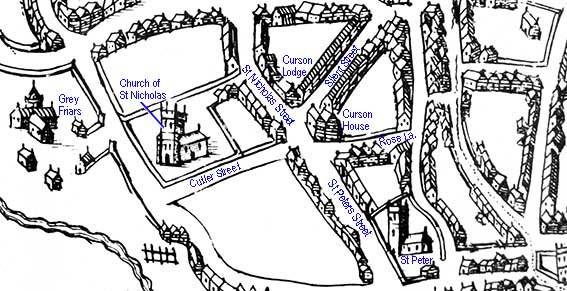

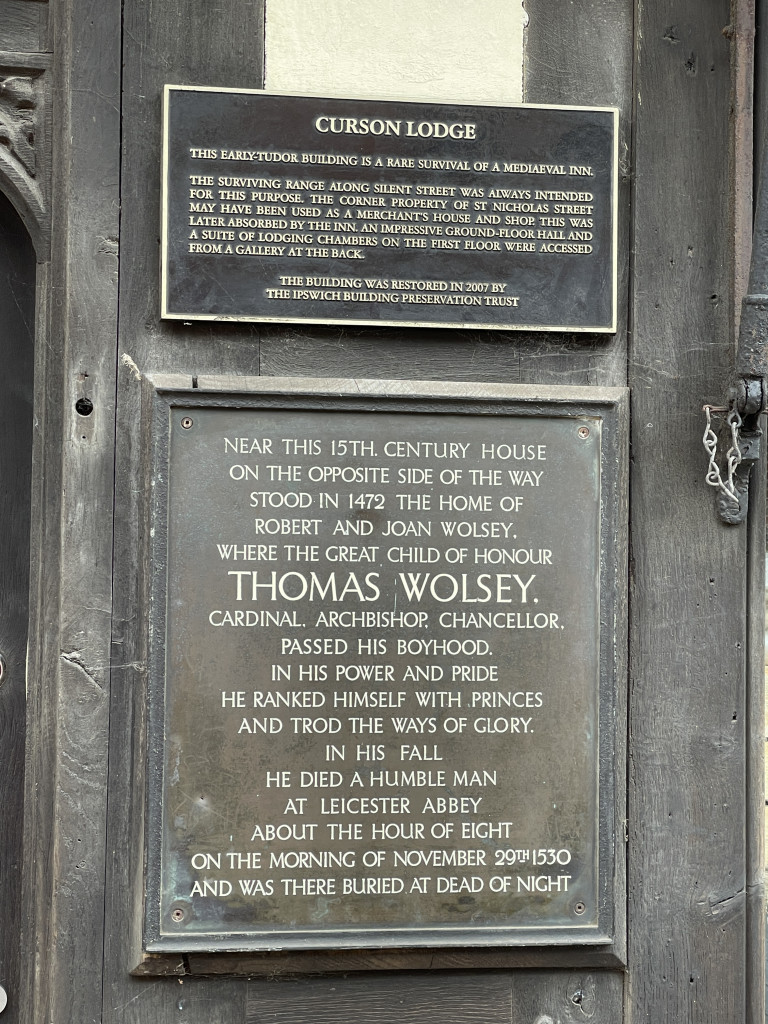

Curson House & Curson Lodge

Curson House was once the grand townhouse of the Tudor courtier, Robert Curson. He is believed to have hosted some important Tudor visitors at his swanky mansion, including Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon. Although Curzon House has been lost, some original medieval buildings remain across the road. This range that fronts onto Silent Street was once known as Curson Lodge. This range of timber-framed buildings would have provided additional lodgings for courtiers travelling with the royal entourage.

While on our walking tour of Ipswich, I was lucky enough to be introduced to the current custodian of one of those houses. He was kind enough to invite us inside, share the building’s incredible history, and show us some of its surviving architectural features. Below is a summary of part of our conversation:

Sarah: We’ve come to meet Daryl, the guardian of this ancient building.

Daryl: My wife and I took over guardianship about five or six years ago. We fell in love with the building and thought it needed looking after.

Sarah: Can you tell us what this building is?

Daryl: Sure, it’s believed to be built as an inn. We know it wasn’t built as a house because of the height of the ceilings and the configuration at the back of the building.

Sarah: As we explore Thomas Wolsey’s association with Ipswich, I imagine this had something to do with Wolsey’s life at some point. What is that?

Daryl: I think certainly he would have known this as a young man. When we took over the building, we were told they thought it had been put up about 1485. After a couple of years, we decided to try to narrow that down and find out a bit more about the age of the building. We decided we’d go to a dendrochronologist. We were lucky that we got permission from the conservation officer here in Ipswich to do some drilling into some of the main timbers on the building.

We were worried as the dendrochronologist said they might not get a precise result because timber growing in the east of England doesn’t have the defined ring pattern it does in the west and the south. However, thankfully, they came up with a date. It turns out that the timber had probably been felled in the winter of 1430, and work would have started the following spring. So, we’ve gone back a whole generation! So, yes, Wolsey would have known this building.

Directly opposite here was the home of Lord Curson. He entertained Henry VIII and, on two occasions, Katherine of Aragon, both of whom had come to visit the Shrine of Our Lady. Legend has it that this building, having been put up as an inn or a dwelling house, may have been used as accommodation for the entourage when royalty came to the town.

Sarah: So what happened to this building over time? And maybe you could point out some architectural features that survive.

Daryl: It’s a rather complicated building. They believe that the building was knocked down, and a wool merchant probably had this new building put up. He wanted to show his wealth, so he commissioned some lovely carvings on outside-facing timbers. These timbers would have decorated an archway that led out into the street, allowing horses and carriages to come and go underneath it. These carvings (shown in the pictures below) survive. However, we haven’t had those timbers dated, so we don’t know the age of the carvings for sure.

Sarah: The wood carving that I’m looking at, is it a dragon?

Daryl: It’s a wyvern, which is a mythical creature with two front legs and a tail and wings. And this one here looks as though he’s facing its young. You can just see there with his teeth open. On the other side of the bracket, they believe that this is a representation of a pomegranate. If it is, that would tie in with Katherine of Aragon. As we all know, the pomegranate was her badge. Again, we don’t know for sure, but we have been told it could be.

Sarah: It’s a beautiful carving.

Daryl: It’s almost church-quality carving, I think – indeed, you see this quality in Suffolk churches. Somebody wanted to show off their wealth. They’d made a lot of money in the wool and cloth industry. This wasn’t St Peter Street in those days; it was ‘King Street’, and it ran down to the river, where most of the business came into town. And the main street, which is close by, would have been the main thoroughfare up into town.

Sarah: That makes so much sense. Thank you for that and for putting the geography in perspective.

Map of Curson Lodge and Curson House, courtesy of ipswich-lettering.co.uk;

Exterior of Curson Lodge; Daryl, Sarah and Phil outside Curson Lodge;

Wooden carvings inside Curson Lodge; Interior of Curson Lodge;

Tudor house next door to Curson Lodge.

Wolsey Statue

Close to the site of Wolsey’s later family home on St Nicolas’ Street is his bronze statue, designed by David Annand. It was unveiled in 2011.

Sarah and Phil by the statue of Thomas Wolsey.

St Peter by the Waterfront & Wolsey’s Gate

St. Peter’s played a crucial role as a church, serving the parish and the mariners arriving in Ipswich’s bustling medieval port. Initially constructed from wood, it evolved into a stone building as part of the Augustinian Priory of St Peter and St Paul in the late twelfth century. During this period, St. Peter’s acquired the impressive Tournai Marble font, crafted from limestone originating near Tournai in Belgium.

In Tudor times, St. Peter’s gained prominence when Cardinal Thomas Wolsey repurposed the church as the chapel for his College of the Blessed Virgin Mary following the closure of the Priory. This era witnessed significant modifications to the structure, including the relocation of the tower, the addition of north and south aisles and the introduction of a new chancel. Today, the ‘Wolsey Gate’, a watergate on College Street, stands as a reminder of Wolsey’s ambitious plans.

Below is a summary of a snippet of a conversation with Phil about the Wolsey’s Gate:

Sarah: Towards the end of Wolsey’s life, in 1530, he’s arrested at Cawood near York to be brought to London. He died at Leicester Abbey at the end of November 1530. And it sounds as though his grand plans for his college were not completed. So what was here at the time, and what was incomplete? Can you tell us a bit more about that?

Phil: There was going to be a large college here called St Mary’s College of Ipswich. Building work had begun. And today, what we have left is a small fragment of much grander plans, including the so-called Wolsey’s Gate. This was once an entrance on the east side of the church. The River Orwell would have come up right up to the gate, but today, it’s a busy road!

The original turret of the College wasn’t pulled down until the 1830s, so, sadly, it doesn’t exist, but it was pulled down to widen Silent Street. So, the Wolsey Gate is the only surviving structure we have now. A seal associated with the College was dug up by a builder near Wolsey’s old Grammar School, the school Wolsey attended as a child. On the seal, you can see that it has an image of Mary the Madonna, and it says ‘Gibswick’ on it, which was the Tudor name for Ipswich. It also bears Cardinal Wolsey’s name.

Sarah: And where is that held?

Phil: So that’s in Magdalen College, Oxford. Also, the foundation stone of Ipswich College was found just at the back of this church, and it states who laid the stone – the Bishop of Norwich. And again, that’s at Magdalen College, where it has been set in a wall.

Sarah: Can you see that stone and that seal at Magdalen, or do you have to visit via special appointment?

Phil: No, it is by special appointment only, as it is in the Great Hall.

Sarah: Now, did Wolsey ever come here? Once he’d founded his grammar school?

Phil: He came to the shrine in 1517 but not to his school. Wolsey put Cromwell in charge of the building work here, in Ipswich. There’s also an account that the Duke of Norfolk came here to Ipswich and even advised Wolsey on the cheapest stone to buy to build his college. I find that interesting because it’s often said that the Duke of Norfolk was an enemy of Wolsey.

Sarah: It is. Wow. That’s amazing. What a rich history!

Wolsey’s Gate; Interior of St Peters; Medieval Tournai marble font with replacement Tudor freestone stem.

Christchurch Mansion

This splendid Tudor manor was constructed upon the former grounds of the Holy Trinity Priory. Following the Dissolution, between 1536 and 1541, the land came into the possession of the Withypoll family, who oversaw the construction of the house between 1548 and 1550.

It has undergone substantial alterations throughout its long history. The final proprietor, Felix Cobbold, who was from another illustrious Suffolk family, transferred the house and its surrounding land to Ipswich Borough Council in 1895. He stipulated that the land be transformed into a park, serving as a valuable amenity for the town’s residents.

Although not directly connected to Wolsey, there is a lovely room clad in Tudor panelling with other early artefacts, which is worth a look,

Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich

Useful Links

Phil’s book, Cardinal Wolsey For King & Country, is available here.

To read my blog about Wolsey’s death at Leicester Abbey, click here.

My Four Day Tour of Tudor Suffolk itinerary details other places to visit nearby.

If you have enjoyed touching the past through this blog, you can join my membership, The Ultimate Guide to Exploring Tudor England, which brings together all my best, most comprehensive content in one place: blogs, videos, live chat, progresses, maps, itineraries, travel information and podcasts.