The 1502 Progress: The Old Manor of Woodstock, Oxfordshire

Itm: the xixth day of July delivered to the Quenes Aulmoner for money by him leyed out in aulmous [alms] from Windesore to Woodstok. Itm: the same day to the Quenes purse at Woodstock by thandes of my Lady Kateryne.’

The Chamber Books of Elizabeth of York, July 1502.

The Old Manor of Woodstock: Key Facts

– According to the Chamber Books, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York arrived at Woodstock somewhere between 19-21 July 1502.

– Sadly, the Manor was destroyed in the seventeenth century and there are no remains above ground today.

– Surviving records show the Manor was built upon a rocky outcrop of land, overlooking a shallow valley with the River Glyme meandering through its base.

– No contemporary floor plan of the medieval, or later Tudor, palace exists. However, records reveal many of the features of the palace.

– Woodstock was unusual in that it had two great halls, one on the Queen’s and one on the King’s side.

The Court Arrives at Woodstock Manor

The Tudor dynasty claimed six major royal houses that could accommodate the entire royal court of around 1000 people. Five of these majestic buildings, Whitehall, Richmond, Greenwich, Hampton Court and Eltham Palaces, were arranged in and around London. The sixth was an extraordinary outlier, situated around 65 miles northwest of the capital: Woodstock Manor in North Oxfordshire.

According to the Chamber Books, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York arrived at Woodstock somewhere between 19-21 July when there are records of the Queen’s Almoner providing alms, presumably to the poor, during the royal journey from Windsor to Woodstock. On the same day, money was received into the Queen’s Privy Purse ‘by the hands of my Lady Kateryne’. Sadly, we do not know which ‘Lady Kateryne’ this refers to.

These are not the only payments made during Elizabeth’s two-and-a-half-week stay at Woodstock. As the Privy Purse Expenses show, the Queen was in constant receipt of gifts, and during her stay at the ancient palace, she was presented with cheese from the Prior of Llanthony Priory in Gloucester, as well as two bucks brought to court by ‘a servant of Lord Mountjoy’ from nearby Cornbury Park.

Llantony Priory was well-known for its cheese: ‘Llanthony Cheese’. On this occasion, it was a gift of its new prior, Edmund Forest. According to Dr Chris Barnes, from Llanthony Secunda Priory, Edmund was prior by 15 September 1501. It is interesting to note that the previous prior, Henry Dene, was particularly close to Henry VII. The king visited the priory on several occasions, including the previous year, when on 7 August, Dene was indeed elected to the Archbishopric of Canterbury.

Upon his election to the archbishopric, he resigned from the priorate. He would officiate at the wedding of Prince Arthur and Katherine of Aragon in November 1501 and, after Arthur’s death in April 1502, would host Katherine at the Archbishop’s summer palace at Croydon, following Katherine’s recall from Ludlow.

As for Lord Mountjoy, this was William Blount, described as the ‘most influential and perhaps the wealthiest English noble courtier of his time.’ He was a renowned scholar and pupil of Erasmus, who called him inter nobiles doctissimus (“The most learned amongst the nobles”). He also happens to be the great-grandfather of Anne Boleyn through the paternal line. Cornbury Park (mentioned in association with Mountjoy) lies west of Woodstock. Today, it is a private estate; interestingly, it is also where Robert Dudley would die over 80 years later. At the time, Dudley was Keeper of the Park.

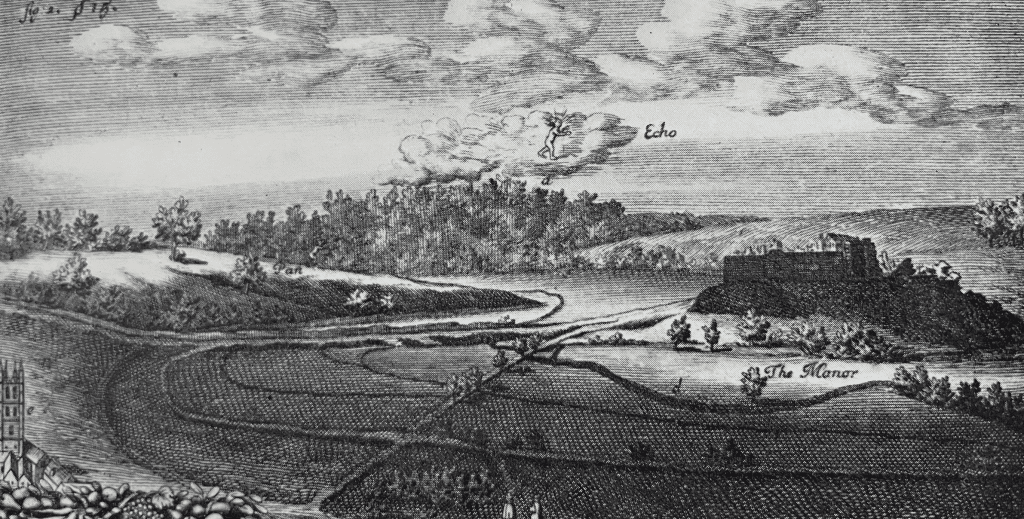

The Old Manor stood on the plateau of land to the right of the bridge.

Looking at the map, it seems likely that the royal couple would have hunted regularly in Cornbury Park during their stays at Woodstock and Langley (as we know Henry VII and Anne Boleyn did on the 1535 progress). I am also guessing that they likely passed through it to reach the next destination on the progress: The Old Manor of Langley. We will return to this shortly in our next entry.

When she arrived at Woodstock, Elizabeth was around 2-3 months into what would prove to be her final pregnancy. Having lost their eldest son in April of the same year, the Queen had famously comforted her grief-stricken husband with assurances that they could produce more children. This turned out to be no empty promise.

The Queen fell pregnant almost immediately, with May cited as the usual date that Elizabeth realised she was once more with a child. We know that Elizabeth’s previous pregnancies had not been without complications and that, at 36, she would be considered quite old to bear children. So, trying for another child to fill the Tudor nursery was likely to be an enormously risky business. It seems to me that this indicates Elizabeth’s wholehearted commitment to her role in bearing sons to maintain the stability of her husband’s dynasty. I am sure Elizabeth must have realised that it was not something to be undertaken lightly.

We know from an entry in the Queen’s Chamber Books in early August that the Queen fell ill while staying in Woodstock, and she paid for an offering to be made at the shrine of Our Lady at Northampton. Payments for such offerings are scattered through the Chamber Books, with others being made around this time at St Frideswides in Oxford, the Church of St Mary Magdalen in Woodstock and ‘the Roode at Northampton…and to oure Lady at Linchelade’. Clearly, Elizabeth feared the consequences of falling pregnant again and hoped her offerings might bring about the safe delivery of her unborn child.

What is interesting, and indeed it has been raised by other scholars, is why Elizabeth chose to undertake something as physically demanding as ‘going on progress’ when she must have been all too aware of how precious this new child would be to the future of the Tudors. Two sons had died within two years, leaving only Prince Henry as the sole male heir, alongside two daughters who could – and would – be married into powerful foreign dynasties.

In modern times, the late Diana, Princess of Wales, would speak about her duty to deliver an ‘heir and a spare’. This is clearly what Elizabeth was trying to rectify when the couple sought to conceive for what would be the seventh time. As I have indicated above, it was a decision made as a direct consequence of Prince Arthur’s death.

During the research of this progress, I was fortunate to meet with Samantha Harper to explore the fascinating history of Fairford and its parish church. Sam was one of the team that transcribed and helped digitalise the Queen’s Chamber Book records. She is clear that this progress was unusual. For example, It contained none of the usual pomp and ceremony associated with the usual royal progress, as we saw during Henry VII’s first northern progress in 1486. Instead, Samantha describes this ‘progress’ to south-east Wales as more like a ‘trip down memory lane’, with the King and his consort heading for Raglan Castle, one of Henry VII’s childhood homes. This was not a progress of ‘State’ but one of grief and healing through connecting with the past.

But what of the place that housed the royal court during the second half of July 1502? Sadly, there are no remains above ground today. The Manor was utterly destroyed in the seventeenth century. Only a stone plinth, erected centuries later, reminds us of the medieval palace that once stood there. Thankfully, there are enough surviving records to allow the modern-day antiquarian to recreate its former glory.

The Appearance of Woodstock Manor

One of the earliest drawings we have of Woodstock Manor comes from Dr Plot’s Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677), which shows the palace before it was demolished and the landscape redesigned by Capability Brown.

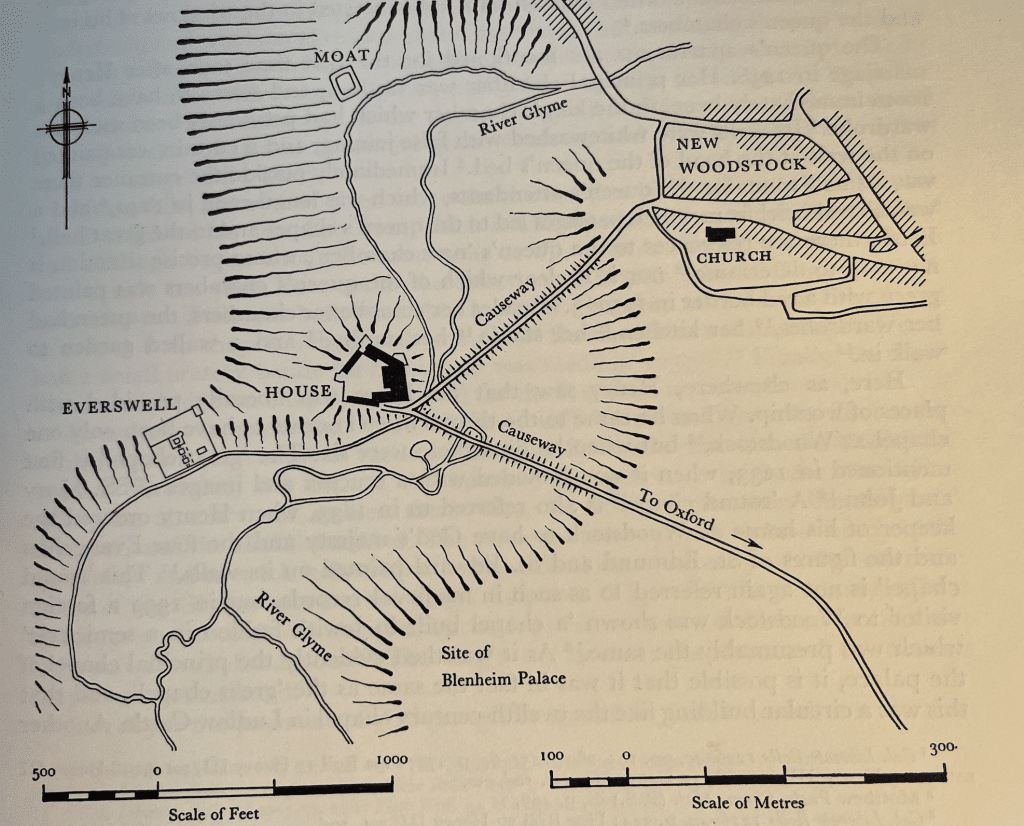

We can see that the Manor was built upon a rocky outcrop overlooking a shallow valley with the River Glyme meandering through its base. Two causeways can be seen. The first is heading to Oxford (around eight miles to the south), and the other, in the foreground, winds its way to the adjacent village of Woodstock. The parish church of St Mary Magdelene can be seen in the bottom left corner of the image.

As mentioned above, absolutely nothing remains of this once noble house. It was obliterated by Sarah, 1st Duchess of Malborough, during the building of Blenheim Palace in the eighteenth century. The reason? It ruined her view from her newly built home!

Yet, Woodstock Manor was the oldest royal palace, constructed by Saxon royalty. Early Norman kings consolidated Woodstock’s position as a major royal residence in the twelfth century. Henry I and then his grandson, Henry II, were responsible for most of its aggrandizement. The latter would inveigle the place with the stuff of myth and legend with the tale of ‘fair Rosamund’, the King’s mistress. Henry II lodged her nearby in a place synonymous with her name. You can read more about it here, in my original article on Woodstock Manor, which focused on the imprisonment of Princess Elizabeth in 1554-5.

The Norman kings regularly visited Woodstock Manor because of the peerless hunting in the extensive woodland surrounding the palace. The convergence of five forests, including Cornbury, Wychwood and Woodstock, resulted in around 500 square miles of prime hunting land. That is enormous!

The Layout of Woodstock Manor

Alongside building accounts recorded in The History of the King’s Works, there are a couple of eye-witness accounts from visitors to the palace before its eventual destruction. One of these is an anonymous seventeenth-century traveller, enigmatically known only as ‘the Lieutenant’. He describes the manor as ‘ancient, strong, large and magnificent’… deeming it ‘sweet, delightful and sumptuous, situated on a ‘fayre hill’.

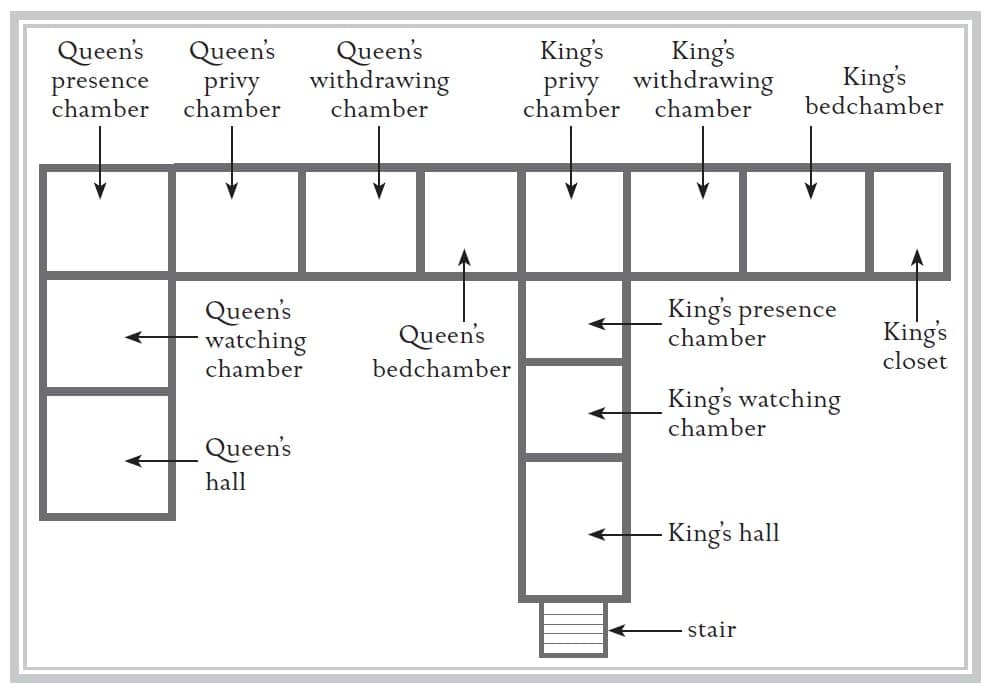

No contemporary floor plan of the medieval, or later Tudor, palace exists. However, accounts recorded in The Pipe Rolls (Financial Accounts from the English Exchequer, dating from the 1100s) reveal many of the features of the palace. Helpfully, Prof Simon Thurley has translated these into a floorplan of the royal lodgings. (Please check out his site at RoyalPalaces.com – you will find the link at the end of this blog).

At this point, I invite you to stroll through the palace alongside our ghostly guide, ‘the Lieutenant’ and let our imagination conjure up this magnificent building once more…

The Gatehouse and Courtyards

The Palace was laid out in an irregular pentagon, measuring roughly 100m long from north to south and the same east to west at its widest points. This is best seen in a map of Woodstock taken from The History of the King’s Works (see below).

The entrance to Woodstock Manor was via a gatehouse on the south side, which the Lieutenant describes as ‘large, strong and fayre’. The History of the King’s Works (Vol. 4, Part II) notes two cant windows over the arch [Note: A cant window is a projecting window with angles, sometimes distinguished from a bow window], two porter’s lodges, two rooms adjoining these and 12 more. There was also an inscription in ‘English rhythmical verse above the gatehouse arch. Translated, this meant: Henry the seventh built these famous houses.

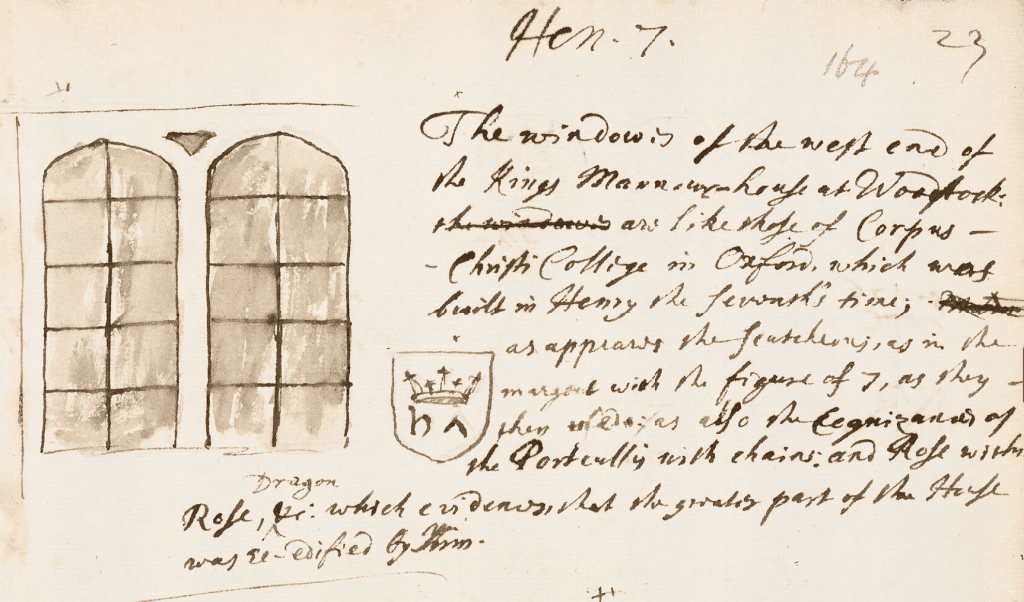

This is a slight exaggeration of the truth. According to seventeenth-century antiquarian Sir Issac Wake, who wrote about the manor in his book dated 1607, called Rex Platonicus, the first Tudor king built only the ‘front and outer court’ and updated and altered many of the existing medieval buildings. Still, this was a significant building project.

Another perspective comes from the notes of John Aubrey, an antiquary, who visited Woodstock a little later in the century, just after the English Civil War. His papers are preserved in the Bodleian Library and include a sketch of a pair of windows whose architectural style fitted with the reign of Henry VII. He notes that the emblems of the Tudor dynasty (the Beaufort portcullis, the ‘rose within a rose’ and dragons) were prevalent in and around the palace buildings. He concluded that the ‘greater part of the house was re-edified by him’.

More specifically, Simon Thurley notes, ‘Henry VII spent over £4,000 rebuilding the house. He put up a new gatehouse, a new roof for the great hall, bay windows, and a jewel house that allowed him to bring his cash when he visited.’ So, while the medieval kings established Woodstock Manor, Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty, showed considerable interest in maintaining the property. He made frequent visits to Woodstock during his peripatetic progresses through England.

Once through the gatehouse, the outer courtyard sounds extraordinary, measuring 3339m2 with a fountain at its centre; this sported five spouts fed by a local spring. On the far side of the courtyard, a stately set of 35 steps ‘of freestone’ [Def: ‘Freestone’ – a type of fine-grained stone, in particular, a type of sandstone or limestone] led up to a porch. This porch was noted to be wainscotted during the medieval period, with the wainscot, door and window shutters all painted green. Beyond the porch was the ‘church-like’ great hall, reflecting the scale of the rest of the palace.

DID YOU KNOW? Did you know that Woodstock was unusual in that it had TWO great halls, one on the Queen’s, and one on the King’s, side?

Into the King’s Lodgings…

The King’s Hall was described as ‘spacious’ hall, with having ‘2. fayre lies [ailses], with 6. Pillers, white and large, parting either aisle, with rich tapestry hangings at the upper end thereof, in which was wrought the Story of the Wild Bore’.

One of the fascinating aspects of the palace was its number of chapels. When Henry II ascended the throne in 1154, there was only one chapel at Woodstock; when he died, there were six. The most curious was accessed from the left-hand side of the King’s Great Hall. It was unusual because it was round, like the surviving round chapel at Ludlow Castle.

The Lieutenant leaves us with his impression of the structure, which he states was a ‘neat, and stately, rich Chappell, with 7. round Arches, with 8. little windowes above the Arches, and 15. in them; A curious Font there is in the midst of it, and all the Roofe is most admirably wrought; the entrance thereunto correspondent to her Selfe, is neat, and lofty, with many curious windowes on both sides’.

Fabulous!

From here, our ghostly guide distinctly refers to ‘ascending from the hall’ into the Guard-Chamber, which ‘look’d big enough’, although he notes that ‘the Keepers were absent’; so he was able to pass ‘uninterrupted’ into the King’s Presence Chamber. This suggests another stair connecting the Great Hall to the latter chamber. The size of this hall and the stately steps leading to and from it must have been quite a majestic sight!

As you can see from Simon Thurley’s floor plan, the King’s Presence Chamber led into the King’s Privy Chamber. This occupied the centre of the confluence between the King’s and Queen’s sides.

Running parallel to the King’s Hall was the Queen’s Hall. This presumably had a similar arrangement to the King’s, with a flight of stairs ascending to the Queen’s Watching Chamber. As shown in Thurley’s floor plan, this joined the Queen’s Presence Chamber. Presumably, sequentially smaller rooms, including the Queen’s Privy and Withdrawing Chambers, connected with the final room in the sequence on the Queen’s side: the Queen’s Bedchamber.

This bedchamber connected directly to the King’s side via his Privy Chamber. This meant that the King could pass privately between his chambers and that of his wife, should he wish to spend the night with her. This practical and cosy arrangement was typical in Tudor royal palaces.

The Lieutenant notes that the King’s Privy Chamber ‘lookes over the Tennis Court into the Towne’, while ‘the King’s Withdrawing Chamber, and the bed-chamber…have their sweet prospect into the Privy Garden’. This places the range of lodgings on the east side of the palace, overlooking the valley and the little town of Woodstock beyond that.

If you were to visit the site today, even though the valley has been flooded to create the eighteenth-century landscape associated with Blenheim Palace, you would still appreciate what a fine view the royal couple enjoyed from their private chambers.

Today, a plinth commemorates the original site of Woodstock Manor. It stands atop the plateau overlooking the now-flooded valley and Blenheim Palace beyond. The whole area is part of Blenheim Park, and with a ticket to the grounds, you can wander across the site of the lost palace between mature trees, which have now claimed the space as their own.

Perhaps you will walk to the easterly edge of the plateau, which faces towards the village of Woodstock, and imagine the lake dissolving away to see the river, snaking through the bottom of the shallow valley, the two causeways leading the visitor to and from the palace. This is the view that Elizabeth of York would have enjoyed during that summer of 1502.

Visitor Information

To visit the site of Woodstock Manor in Blenheim Park, check out the Blenheim Palace website...and, of course, visit the later palace too. It’s a World Heritage Site, the birthplace of Winston Churchill and the only non-royal palace in England. During the summer, jousts are often held on the grounds, taking us back to its earlier medieval and Tudor history.

THE NEXT STOP ON YOUR PROGRESS IS THE OLD MANOR AT LANGLEY: Click here to continue.

Other Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest:

The Star Inn, Woodstock: I once read that this was where a young William Cecil based himself while Princess Elizabeth was being held under house arrest at the Manor. I have not yet been able to confirm this fact, but this is intriguing, and it is on my ‘to-do’ list to find out more!

There are one or two other places that you should consider looking into while you are in the area. The first is a building in Woodstock itself. You could easily miss its history!

To reach the inn from inside Blenheim Park, walk through the Park with the lake on your left, exiting via one of the back entrances to Blenheim. This leads onto Park Street. Walk down Park Street to the centre of the village. You will find the inn in the marketplace on your left. The inn still functions as a good, old British pub.

Oxford (10 miles): Don’t forget to explore the City of Oxford. It is about 10 miles to central Oxford from Woodstock, travelling in a southerly direction. Transport is by car or bus. There is no train station at Woodstock.

Many of Oxford’s colleges are medieval or Tudor in origin. Some of the best and most historic include Christ’s College, Magdalene (pronounced Maudlin) College, Oriel College, New College, Merton College and Trinity College. If you need up-to-date information on which colleges can be visited, their opening hours and entrance fees, click here.

Of course, from a Tudor point of view, Oxford is perhaps best known for the Oxford Martyrs: Thomas Cranmer, Hugh Latimer and Nicolas Ridley. All were executed on the orders of Mary I by being burnt at the stake just outside the City walls in 1555 & 1556. This area now lies in the heart of the city. You need to make your way to Broad Street. A small area paved with granite setts forms a cross in the centre of the road, outside the front of Balliol College. This marks the site of their execution. The Victorian spire-like Martyrs’ Memorial, at the south end of St Giles’ nearby, commemorates the events.

Also, about 100 m or so away from the place of execution of the three men, you can view the heavy, oak door from the Bocardo Prison, where Thomas Cranmer was held during part of his house arrest in Oxford. However, he also spent time in luxurious surroundings, including a brief stay with the Dean of Christ Church College. Bocardo Prison once sat above the City’s north gate but has long since been destroyed. To see the door to Cranmer’s cell, you must pay to access the nearby medieval tower of St Michael at the North Gate.

Finally, visit the University Church of St Mary the Virgin. It was here that the three men were publicly tried and then brought just before being led to their execution. It is pretty amazing and poignant to stand where these dramatic events unfolded.

Sources

Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York: Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger. Amberley Publishing. 2013.

The History of the King’s Works, Volume II: The Middle Ages, ed. by H.M Colvin. London: HM Stationery Office, 1963 p. 1009-1017.

The History of the King’s Works, Volume IV: 1485-1660, ed. by H.M Colvin. London: HM Stationery Office, 1982. p. 349-355.

A Chronicle of England During the Reign of the Tudors from AD 1485 to AD 1559, by Charles Wriothesley.

A relation of a short survey of 26 counties observed in a seven weeks journey begun on Aug. 11, 1634, by Captain; Legg, L. G. Wickham (Leopold George Wickham), b. 1877; Ancient; Lieutenant. p.118-119.

John Aubrey’s Oxfordshire Collections: An Edition of Aubrey’s Annotations to his Presentation Copy of Robert Plot’s Natural History of Oxfordshire, Bodleian Library Ashmole 1722, by Kate Bennett. p.77.

Actes and Monuments, by John Foxe, p294-295.

A Journey Into England, by Paul Henztner (1598). Horace Walpole, ed. 1757.

One Comment