The Burial of Anne Boleyn and the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula

The Tower of London has had its fair share of legendary inmates, including perhaps the most famous of all, Queen Anne Boleyn.

Over the centuries, many prisoners spent their final days in its ancient walls. Your status was a key factor in the conditions in which you could expect to be kept during your incarceration. We know that Anne Boleyn was lodged in the royal palace, and the apartments were refurbished for her coronation in 1533. But what about the others, including those of lower social status? Where were they housed, and what conditions did they endure?

At the spookiest time of year (Halloween), join me as I seek to answer some of these questions with our expert guide from Historic Royal Palaces, Alfred Hawkins, Assistant Buildings Curator. Together, we explore some of the well-known and much less well-known nooks and crannies of this notorious fortress/palace and prison.

Along the way, we will take you into the Bell Tower, which was the site of imprisonment of Thomas More and John Fisher; The Beauchamp Tower; the place of Sir Walter Raleigh’s incarceration – the Bloody Tower; the site of the lost royal apartments; a low-status cell and the infamous ‘long room’ – the place in which unfortunate prisons were tortured.

We also pause outside the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, the ancient parish church of the Tower community. Of course, this was the place in which some of the Tower’s most high-status prisoners were buried after their execution. So, to accompany this podcast, I am spotlighting an earlier blog, The Burial of Anne Boleyn and the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula, and the fascinating story of her later exhumation.

At the end of this blog, I have also included a gallery of images associated with my visit to the Tower. To listen to the podcast, click here.

Image: Author’s Own.

When Anne Boleyn was executed within the precinct of the Tower of London on 19 May 1536, no provision had been made for her burial. She had died a convicted traitor, guilty of adultery, incest, and treason. Henry had already washed his hands of her and would marry his third wife, Jane Seymour, within days. The late queen’s dramatic downfall had been as ruthless as it had been swift. As her decapitated corpse lay oozing its last vestiges of life, it fell to those ladies who had accompanied their mistress to the scaffold to care for her body.

Shockingly, little thought seems to have been given to the burial of Anne Boleyn. An elm trunk, that had been used to store arrows, was hastily requisitioned as a make-shift coffin. Anne’s ladies, ‘half dead’ themselves, wrapped their mistress’ decapitated body in cloth before the coffin was carried into the nearby chapel of St Peter ad Vincula. Here, Anne was buried in a shallow grave in front of the high altar and next to her brother, George, who had been laid to rest there following his execution just two days previously, on 17 May. They would be the first two sixteenth-century burials in that spot, but they would, sadly, not be the last.

In this blog, we will illuminate the sorry tale of Anne’s burial at the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula and the fascinating later exhumation of her body. Along the way, you will find out exactly why, in the nineteenth century, her bones spent five months out of the grave in which they had lain for over 400 years.

The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula: A Brief History

The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula is one of two chapels embraced by the formidable walls of the Tower of London. The first is the Chapel Royal of St John, situated within the White Tower. This divine Norman chapel is one of the oldest in London and was once adjoined directly with the early medieval royal apartments.

On the other hand, the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula sits in the outer bailey of the Tower, close to the north-west corner of the Tower precinct and overlooking an area that, today, is called Tower Green. It is an unassuming building, and its architecture is not immediately reminiscent of the sixteenth century, but it most certainly is a sixteenth-century building, having replaced an earlier, medieval structure that was badly damaged by fire.

The original chapel was probably built in the early twelfth century (although some say it predates the existence of the Tower itself) and interestingly lay outside of the Tower’s fortifications. Thus, during this early period, the chapel was a parish church, allowing the king and queen to be seen worshipping in public when not hearing mass in the privacy of the Chapel of St John.

It was not until the thirteenth century that St Peter’s was brought within the walls of the Tower’s fortifications, becoming a place of worship for its inhabitants. At this point, during the reign of Henry III, a vault was built underneath the chapel. This vault is the only surviving part of the early medieval church, which remains to this day beneath the north aisle of the current Tudor building.

There are detailed records from the reigns of Henry III and Edward I about embellishments and changes to be made to the chapel over the centuries; from the latter, it is clear that the king and queen regularly worshipped among the men of the garrison based at the Tower.

However, in 1512, a fire swept through the building, destroying it and prompting yet another iteration of the chapel to rise up from the ashes. The building we see today was built around 1519-1520. When you visit the Tower, you might be surprised at how plain and unassuming it is for a royal chapel: it consists of a nave and chancel under one roof, lit by three south-facing windows, with a north aisle adjacent. However, it is not the appearance of the chapel that lovers of Tudor history come to see, it is to touch history by standing in a place smeared with the blood of the innocent.

The Burial of Anne Boleyn

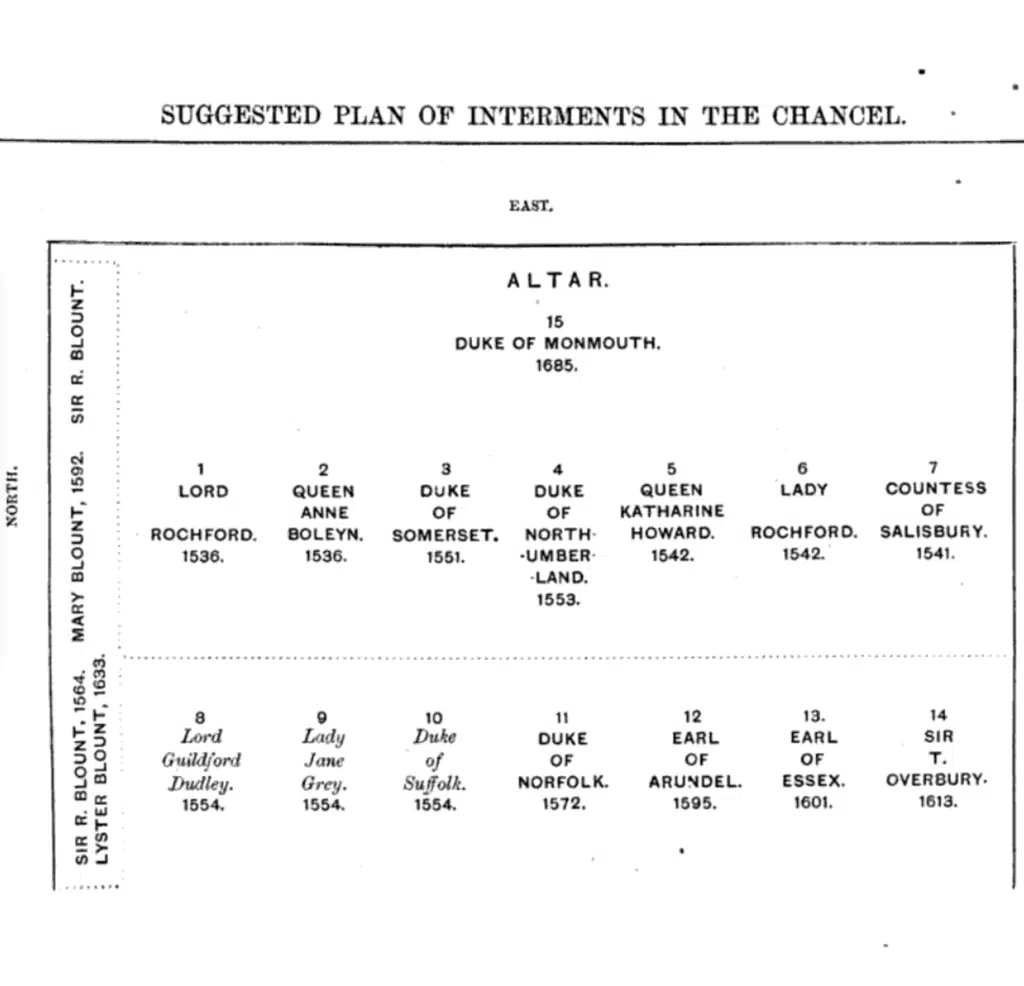

As we have already heard, Anne Boleyn was the second person to be laid to rest in front of the high altar of the chapel during the bloody days of the sixteenth century. In total, 13 men and women of note would follow her and George to their graves there during the Tudor era. These included including Catherine Howard, Lady Jane Grey, Lady Jane Rochford, Edward, Duke of Somerset, and John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. A plan of their projected burial positions is included in Doyne C. Bell’s account of the exhumation and reinterment of Anne Boleyn and other notables (see below).

Of course, dying accused of treason resulted in a deliberate and intended after-life of obscurity. The graves were not marked, although a register of the burials was kept. Furthermore, we have contemporary accounts confirming Anne Boleyn’s grave placement. John Stow, the Chronicler, is the first account to survive. He drew upon an eyewitness account of the events occurring between July 1553 and October 1554, capturing the titanic struggle for the throne of England following the death of Edward VI.

Whoever the mysterious diarist was, he recounted the deaths of John Dudley, Lady Jane Grey, and Guilford Dudley. He provides a detailed account of the death of the Duke of Northumberland (and the two men who died with him), concluding with, ‘Theyr corpse with the hedes were buryed in the chapell in the Tower, the duke at the high alter…’. Stow writes in his Chronicle that Dudley was buried next to the body of Edward, Duke of Somerset, ‘so that there lyeth before the high altar in St Peter’s church two dukes between two queens…the Duke of Somerset and the Duke of Northumberland between Queen Anne, and Queen Katherine, all four beheaded’.

Bodies of more unfortunates would follow over the next 200 years. In addition, it was also used as a burial place for inhabitants of the Tower and even burials of residents in the neighbourhood were ‘freely permitted’. Garrisons stationed at the fortress had also used the chapel for worship such that, over the centuries ‘various additions had reduced the building to a condition more resembling that of a neglected and insignificant parish church, than that of the Royal Chapel’. One visitor expressed his ‘disgust at the barbarous stupidity which has transformed this interesting little church into the likeness of a meeting house’. Aesthetics aside, the chapel faced more serious and pressing problems by the mid-1800s.

In 1876, a plan was submitted for the full restoration of the church, partly to install new heating but also for imperative ‘sanitary reasons’. The intent was to take out the ‘high pews and unsightly galleries’, to mend broken and uneven pavements, and refurbish the interior decoration by removing whitewash and ‘unimportant tablets’ disfiguring the chapel’s walls and columns. This was not the first restoration work to be done to the chapel.

Some 15 years earlier, a south-facing Elizabethan porch had been removed, and the original west-end entrance, which Anne’s body would have been carried through to reach its final resting place, was reinstated. Fragments of the original window that once was sited above the west door were found during this work, and the window was recreated. At the same time, a lathe and plaster covering was removed from the ceiling, revealing the ‘old chestnut beams of Henry VIII’s roof’.

However, the plans of 1876 were for a full restoration to architecturally restore the chapel to its original condition. One of the most serious problems those overseeing the work faced was that the pavement ‘had sunk and become uneven in many parts’. Upon lifting the flagstones and carefully excavating the ground, it was found that those bodies ‘buried within the walls of the chapel during the troublesome times of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, had been repeatedly and it was feared almost universally desecrated’.

All the remains found beneath the chapel floor were ‘carefully collected and enclosed within boxes, with suitable inscriptions; and all the coffins which were found intact were at once removed to the crypt’. A concrete floor was relaid, rectifying the parlous state of the chapel’s foundations. However, at this point, the area just in front of the high altar, where Anne Boleyn had been buried, remained untouched.

The intention had been to leave the chancel undisturbed because of the notable people interred there. The original plan had been to simply relay a pavement on top of the original, but a survey of the ground necessitated a rethink. Doyne C. Bell states this was ‘practically impossible, as in two places the pavement had sunk and showed signs of considerable hollowness beneath it’. The excavation on the spot of the burial of Anne Boleyn was commenced with ‘the greatest caution’. The earth was removed one spadeful at a time, and everything was sieved to ensure that no fragments of bodies were lost during the works.

Finding the Body of Anne Boleyn

On 9 November 1876, at 12.30 in the afternoon, five men gathered in the chancel of St Peter’s, in front of the high altar. Bell had produced a plan of the position of the burials known to occupy the space in front of the high altar. They began the excavations in the place where Anne Boleyn was thought to be interred by lifting the pavement and removing the earth to a depth of two feet, where the remains of a body were found, the bones all heaped together in one concentrated spot.

Clearly, the area had been disturbed before. Upon excavating the ground by a further two feet, the collapsed and decayed coffin of a 54-year-old woman, Hannah Beresford, who had been buried there in 1750, was found. This had been the cause of the localized pavement collapse, and it was concluded that the bones of Anne Boleyn had probably been disturbed at that time.

Working with the team was Dr. Frederic J. Mouat, a surgeon, and local government inspector. He had been given the task of forensically reviewing any remains found. In relation to these bones, he ‘at once’ pronounced them to be:

‘a female of between twenty-five and thirty years of age, of a delicate frame of body, and who had been of slender and perfect proportions; the forehead and lower jaw were small and especially well-formed. The vertebrae were particularly small, especially one join (the atlas) which was that next to the skull, and that they bore witness to the Queen’s ‘lyttle neck‘. A later, more thorough examination concluded: The bones of the head indicate a well-formed round skull, with an intellectual forehead, straight orbital ridge, large eyes, oval face and rather square full chin. The remains of the vertebra, and the bones of the lower limbs, indicate a well-formed woman of middle height, with a short and slender neck. the ribs show depth and roundness of chest. The hand and feet bones indicate delicate and well-shaped hands and feet, with tapering fingers and a narrow foot.

Note: no sign of a sixth finger, folks, or indeed a ‘shew of naile’ noted in by George Wyatt in his sixteenth-century account! Even Bell says in the forensic report that ‘it was first thought that this malformation could be traced on one of the finger bones, but a more careful examination dissipated that impression’. Bell goes on to suppose that their findings line up with known descriptions of Anne Boleyn and the face of a woman who appears in Holbein’s purported image of Anne, which was in the collection of the Earl of Warwick at the time. Bell lists a more detailed description of all the bones unearthed from the burial of Anne Boleyn (Bell p 28). He notes that she could be estimated to have been about 5ft or 5ft 3 inches tall from her bones – ‘not more’.

All the gentlemen present were in ‘no doubt’ as to the identity of the female in question; not only on account of the forensic appearance of the bones but that they lay on the right, or ‘dexter’ side of the altar (with one’s back facing the altar), the position of highest honour. The burial of Anne Boleyn had been one of the first, just two days after that of her brother.

It makes sense that the bodies were buried much like words that are written upon a page, from left to right. However, the bones of George Boleyn, Lord Rochford, were not uncovered. Bell mused that it might have been that they lay more to the north (the left) from where they had excavated and that it was ‘not considered desirable or necessary to examine the ground [there], especially as it might have affected the stability of the Blount monument’.

All the excavated remains were gathered up, carefully sorted, and placed into boxes that were given to the custody of the Resident Governor of the Tower. They were stored in his residence at ‘The Queen’s House’, a late Tudor building south of Tower Green. Two days later, the men returned to complete the excavation on the south side of the chancel, where the pavement had also badly decayed.

Many more bodies were found, including, it is believed, the remains of Jane Rochford, the Countess of Salisbury, and John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. Once again, later burials were uncovered, explaining the displacement of many of the earlier skeletons and the cause of the collapse on this side of the pavement, proceeding from a later, early nineteenth-century burial.

The Reinterment of Anne Boleyn

Five months later, on Friday, 13 April, at Midday, seven men, including the Chaplain of St Peter’s, gathered once more. This time, the remains of each of the bodies had been placed in separate, specially-made caskets. Bell describes them as ‘thick, leaden coffers’ which had been ‘fastened down with copper screws in boxes made of oak plank, one inch in thickness’. An escutcheon engraved with the names of the dead, the year they died, and the date (1887) of their reinternment was affixed to the top of each casket.

The men watched as the boxes were reburied just four inches below the surface of the ground, carefully noting each one’s position. A stable concrete foundation was put down, and a fine, decorative tiled floor, marking the site of each person’s burial, was laid. According to Bell, a plan of the internments was recorded on vellum and, subsequently, was ‘deposited among the records belonging to the Tower’.

Thus, our sad tale of the burial of Anne Boleyn, her exhumation and reinterment, concludes here. After their deaths, Anne and some of those buried alongside her were sadly not left to ‘rest in peace,’ as the ground in front of the high altar was used and reused for subsequent burials. For a brief five months over the winter of 1886-7, Anne Boleyn resided once more above ground, although not in the royal apartments as she once did, but still within the confines of the Tower, forever its prisoner. At least we now know that her grave is properly marked, and if you are lucky, you can visit it today upon the anniversary of her execution and lay your flowers on the pretty tiled floor.

If you enjoyed ‘The Burial of Anne Boleyn’ why not check out another of my Anne Boleyn blogs, in fact, one of my most popular, Anne Boleyn’s Execution: The Surprising Truth.’

Sources:

When writing about the burial of Anne Boleyn, I consulted the following sources:

Notices of the Historic Persons Buried in the Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London by Doyne C. Bell. London: 1877.

The Chronicle of Queen Jane, and of two years of Queen Mary, and especially of the Rebellion of Sir Thomas Wyat, by Nichols, John Gough, 1806-1873.

Annales or a General Chronicle of England by John Stow, p615

A chronicle of the kings of England from the time of the Romans government unto the death of King James, Sir Richard Baker. London: 1670, p315.

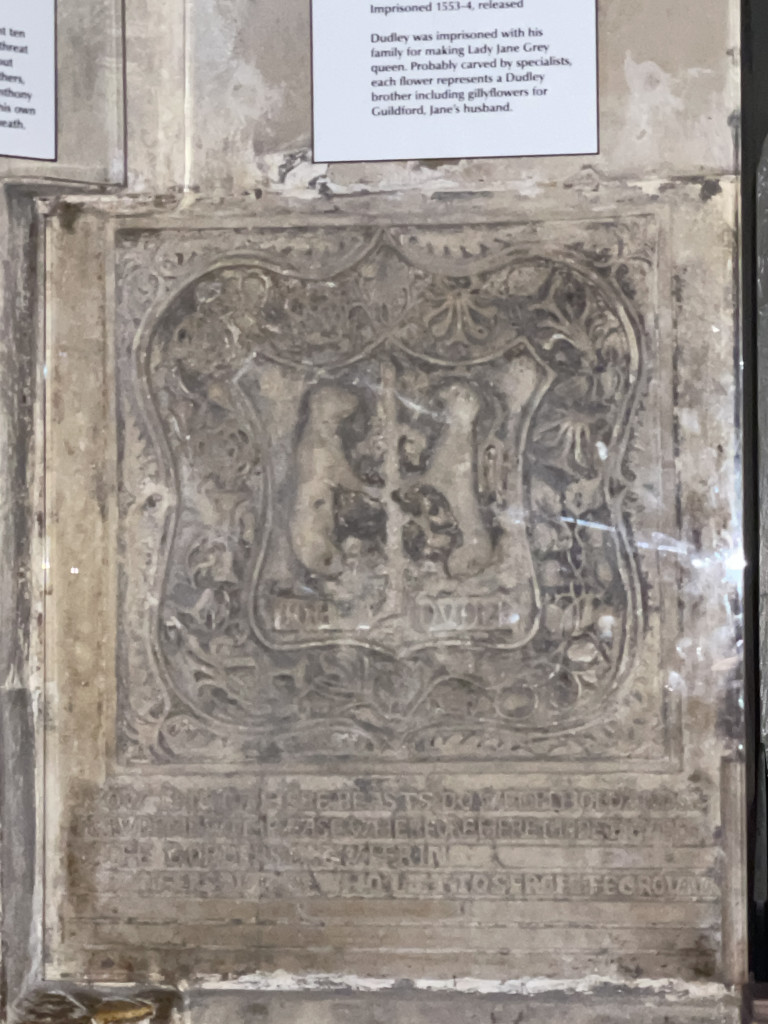

Gallery of Images

This gallery of images is associated with a podcast from The Tower of London. Joined by Assistant Buildings Curator Alfred Hawkins, I explore some of the well-known and much less well-known nooks and crannies of this notorious fortress/palace and prison.

To listen to the podcast, click here.

You may also find this video interesting – it details the now lost apartments that Anne Boleyn stayed within prior to her Coronation in 1533, and prior to her Execution in 1536.

To find out more about Historic Royal Palaces click here, for information on visiting The Tower for yourself click here.

The images in this gallery are the author’s own.

Such a sad and brutal end, vividly brought to life by your wonderful reinactments Sarah, they have moved me to tears several times. We become detached from just how terrible it must have been. To be accused of such crimes, then to know that you will suffer a brutal end, that your sibling and friends will also die, that you will never see your beloved child again. It must have been unbearable.

I echo what Carol Kennedy said in her post. Anne Boleyn is so often just “another historical figure” but your video diary brought her to life, showing her as a real person with the conflicting emotions she must have had in the weeks leading up to her death, far more vividly than any book.

I was gripped by your performance which was well researched and brought up so many details. Well done Sarah. More please X

Such a sad end! Very touchingly written Sarah and I thank you for that!

Thanks, Mark!