Old London Bridge: Traders, Travellers & Traitors

What if you could time-travel to Tudor London? What places would be on your ‘must see’ list? I have a few; Whitehall Palace, the Old Palace of Westminster, Old St Paul’s, Cheapside, The Tower of London and The King’s Manor at Chelsea to name but a few. However, one iconic building that would have to be near the top of my list would be Old London Bridge; I am fascinated by it and rue the day that this incredible, gravity-defying structure was dismantled.

Tudor London must have been a fascinating place; a growing, cosmopolitan metropolis, bursting with so many notable medieval and Tudor landmarks that it would simply make a modern time-traveller’s head spin. In its blog, we are going to focus our attention on Old London Bridge, which once connected the City of London on the north bank of the Thames, with the colourful suburb of Southwark on the south bank.

A Brief History of Old London Bridge

There had been a bridge at this particular point across the River Thames since Roman times. Initially, it was a wooden structure and was constructed at the widest point on the river that the Romans were able to build a viable bridge; and so they did and the walled Roman city of Londinium grew up around it on the north bank of the Thames.

For centuries, Old London Bridge provided a vital crossing point into the City of London for anyone travelling from the south, so that during the Tudor period, if unable to use the bridge, a traveller would have had to make a significant detour inland to find the next nearest point to cross the Thames.

Owing to the fact that wood is a highly degradable material around water and needed constant replacement, and also because several fires destroyed parts of the bridge at various times over the centuries, the wooden structure had numerous iterations over its lifetime. It was finally replaced by a more durable stone bridge in the twelfth century. The master bridge builder responsible for its construction was Peter de Colechurch. As was common in those days, this man was not just an architect and builder, but also a priest at St Mary Colechurch, a church that once stood in the City at the junction of Poultry and Old Jewry (and which was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666). Under Peter de Colechurch’s supervision, the building of the new bridge began in 1176 and continued for 33 years. Constructing a stone bridge spanning around 1000 feet of a fast-flowing tidal river was an epic endeavour: a wonder of the medieval age!

When completed, the bridge was dedicated to Thomas Beckett by Henry II, a man whose life was almost contemporaneous with the building of the bridge. The unfortunate Archbishop of Canterbury had been slaughtered in his own cathedral just 6 years before the construction of Old London Bridge began. In honour of the newly created saint, de Colechurch built a fine chapel on the bridge. The upper chapel opened at street level, whilst a lower crypt was reached via a spiral staircase from the water. It soon became the traditional starting point for pilgrims making their way to Canterbury to pay their respects at Beckett’s shrine. Already the bridge was set to be a thriving centre of commerce!

Sadly, Peter de Colechurch did not live to see his masterpiece completed. He died in 1205, 4 years before the bridge was finished. This did mean, though, that his body could be laid to rest beneath the chapel floor, and thus it laid entombed in his own magnificent construction for the next 600 years.

London Bridge in the Sixteenth Century

At not far off 1000ft wide (905ft to be precise), the Old London Bridge comprised 19 narrow arches, supported on starlings, which were embedded into the river bed. As de Colechurch had to drive the elm posts into places where the river bed was firm, it resulted in the irregular spacing of the aforementioned arches; this asymmetry is clear on some of the images of the bridge around this time.

The effect of these arches was to reduce the space that the water had to flow downstream by up to 70-80% (NB: I have read various figures relating to this fact, and indeed this number did change over time as new ‘obstructions’, such as the Elizabethan corn mills, were added later in the sixteenth century. They had the effect of impeding the flow of water passing under the bridge to an even greater extent). This impediment to flow caused a difference between the height of the river on either side of the locks (as they were known) of some 6ft at low tide. This was called ‘The Fall’ and created sections of fast-flowing water between each arch (which, by the way, were individually named and were even given nicknames by boatsmen most familiar with them, such as ‘Gut Lock’ and ‘Long Entry’).

These rapids were highly dangerous to navigate, and very many people drowned whilst attempting to do so. Sailing a boat between the pillars was called ‘shooting the bridge’. The high casualty rate from this notorious section of the Thames resulted in the famous saying that London Bridge was ‘for wise men cross over and for fools to go under’. So did this mean that Henry VIII, each of his wives and high-status courtiers gambled with their lives on a regular basis as they moved by barge up and down the Thames?

Apparently, there is no record of Henry VIII avoiding ‘shooting the bridge’, although it is hard to envisage that he would put his life at risk so unnecessarily. However, we do know that Cardinal Wolsey fastidiously refused to do this on his many journeys from York Place and Hampton Court to visit the king at Greenwich. Instead, he insisted on disembarking upstream of the bridge. The usual point was at ‘The Three Cranes’ in Upper Thames Street. Wolsey then travelled by mule down Thames Street before embarking once more at Billingsgate, the usual point of re-entry.

Almost as soon as the bridge had been completed, buildings began to be built on it along either side, eventually leaving a narrow, 12-foot wide roadway along which both north and southbound traffic was required to pass. By the Tudor period, there were around 200 houses and shops on the bridge, some rising to 3-6 storeys! Whilst numerous latrines (both private and public) projected outwards from the bridge to deposit their contents directly into the river below, the upper levels teetered inwards, creating a dark passageway beneath. Because of the compact nature of the buildings, it was said that you could walk halfway across the bridge and yet be unaware that you were out over the water! This account, from Thomas Pennet, an eighteenth-century traveller, described how it felt to experience the sights and sounds of old London Bridge:

‘I well remember the street on London Bridge, narrow darksome and dangerous to passengers from the multitude of carriages; frequent arches of strong timber crossed the street, from the tops of the houses, to keep them together, and from falling into the river. Nothing but use could preserve the rest of the inmates, who soon grew deaf to the noise of falling waters, the clamours of the watermen, or the frequent shrieks of the drowning wenches’

Old London Bridge and its Buildings

Apart from the chapel of St Thomas Beckett, located near the centre of the bridge, there were some other notable buildings and features that are worthy of mention. Like its wooden predecessor, old London Bridge had a central drawbridge where the river was at its deepest, so that tall ships could sail upstream at high tide. An ornately decorated wooden gate, known as Drawbridge Gate, stood at the northern end of this central drawbridge. More on that structure in a moment!

A second drawbridge was located at the Southwark end of the bridge. Both of these drawbridges performed a vital defensive role when the city was under threat. More than once they were raised to prevent insurrection and defend the city from attack. One such notable event, occurring during the Tudor period, was the Wyatt Rebellion against Mary I and her planned marriage to Phillip of Spain. Wyatt’s troops tried to cross old London Bridge, but it was overrun by Mary’s supporters. No doubt the drawbridge was raised, forcing the troops to turn back and try to cross the river some distance upstream at Kingston.

The Traitors of Drawbridge Gate

We have already mentioned Drawbridge Gate. This mighty gatehouse became well known as the place where the severed heads of traitors and various limbs (or quarters) were placed on spikes for all London to see following their execution. Unbelievably, there were often so many heads and limbs on display that a ‘Master of the Heads’ was appointed to manage the ‘congregation’! He was responsible for putting the gruesome artefacts on spikes and disposing of them into the river at the appropriate time.

Sometimes the heads were left there for months, if not years. Apparently, the whole spectacle was quite a tourist attraction! William Wallace was the first victim whose head was displayed there in 1305, and famously during the Tudor period, Sir Thomas More’s head was also placed on display above the gate. It was later retrieved by his devoted daughter, Margaret Roper. One assumes she may well have bribed the Master of the Heads to get her father’s head back!

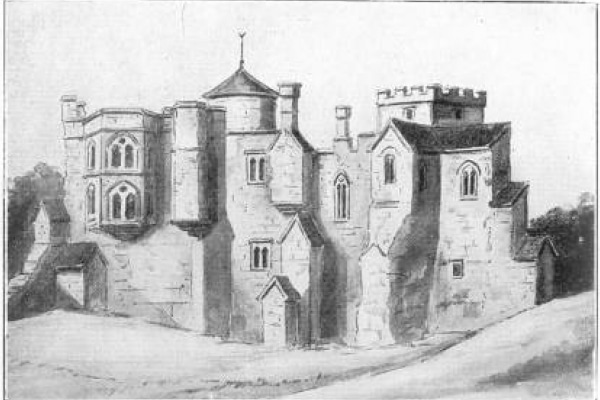

However, during the Elizabethan period, Drawbridge Gate was dismantled and replaced by a spectacular prefabricated building shipped to England from Holland – Nonsuch House, which was built in 1577. Possibly used as the Lord Mayor’s residence, it became THE most desirable house in London. As a result, the heads of traitors were moved to the gatehouse on the Southwark end of the bridge (shown in the image above). This practice continued in London until well into the seventeenth century.

The End of London Bridge

Interestingly, whilst many people drowned trying to navigate under the bridge or, presumably, falling from it, the recorded incidence of disease occurring on the bridge was low compared to those rates clocked up in the City of London. For example, during one outbreak of the plague, which carried off many Londoners in the City, there were only 2 recorded cases on the bridge. It is thought that the fresh air (if you have ever taken a boat trip down the Thames you will know that even when the city streets are stifling in summer, there is often a refreshing breeze over the water), together with the access to a natural system for sewage disposal, were responsible for creating a relatively healthy environment. This was part of the reason that the bridge became such a desirable place to live.

However, in the eighteenth century, after London was rebuilt following The Great Fire of 1666, cramped streets were being swept away in favour of wider thoroughfares and open squares; sanitation systems and freshwater were becoming more widely available, and so the rampant and deadly diseases, which had so afflicted London in days gone by, rapidly diminished. In contrast, London Bridge remained cramped and a serious traffic bottleneck. People wanted a wider bridge, and so the death knell tolled for this iconic structure, which held the record for being the longest inhabited bridge in Europe. Safe to say that it was surely a medieval marvel!

Nice photos! Thank you for sharing!

You are welcome!

Amazing history – if only we had kept a version of the medieval bridge then built another more modern and practical one alongside it…..one is reminded of Bath and also Florence – a great tourist attraction – where one of the original bridges had been sufficiently preserved over time…

I did not know that we too had used wood driven into the river bed – it makes sense of Venice and their sad problems of sinking more comprehensible.

Absolutely. I too have seen the one in Florence…so sad we lost this bridge. can you imagine what an amazing tourist attraction it would have been? It would have been like Diagon Alley! Thanks for reading and commenting!