Tudor ‘Houses of Power’ with Prof Simon Thurley

In this month’s episode of The Tudor Travel Show: Extra! Sarah is in conversation with Professor Simon Thurley, a pre-eminent architectural historian, specialising in Britain’s built environment. Sarah talks to Simon about the Boleyn properties of the early sixteenth century when the family was at the height of its power. She also explores with Simon the delights of his most recent book on Tudor buildings: Houses of Power.

Note: This blog on Tudor ‘Houses of Power’ is an abbreviated transcript of that conversation, which you can also listen to in full here.

The Boleyn ‘Houses of Power’

Sarah:

Welcome, Simon, to The Tudor Travel Show. It’s a total delight for me to have you here. As I think you know, you are one of my favourite authors in the Tudor-sphere and it would be great to be able to hear a little bit from you about the work that you are doing now. Most recently, I saw you on the Gresham College website, where you were delivering a lecture about the Boleyns property portfolio and their House of Power in the early sixteenth century. We are going to talk more about the Boleyns today. But before we dive into that, you also gave a lecture on a similar theme, but this time wrapped around the Cecil family. I was curious about why you picked those two families. Was there a particular question you were hoping to answer as you pulled together the work to deliver those lectures?

Simon:

Essentially, I chose families who acquired their wealth and their success in slightly different ways. The Boleyns are extremely interesting because they became an enormously wealthy landowning family with a huge number of properties and a huge amount land and, of course, their most famous child became, by default, the greatest landowner in England of them all. So it’s an aspect of a very, very well-trodden path that hadn’t really been looked at before. The Cecils likewise; although they came to power via a different route, through their skill in administration, they amassed an equally, and arguably even more impressive, portfolio of buildings and estates at a period when the monarchy was not so interested in doing that. Henry VIII, if he had seen any of the Cecil houses, would have licked his lips and probably persuaded them to give them over to him!

Sarah:

Well, let’s look at the Boleyns in more detail. One of the things that I found to be most interesting in your lecture was how you talked about Hever in relation to some of the larger Boleyn properties, Rochford Hall and Luton Hoo, for example. Everybody knows a lot about Hever, but maybe not so much about Rochford Hall or Luton Hoo. Can you tell us a little bit about those properties and, in particular, how they might have appeared during the sixteenth century when the Boleyns owned them?

Simon:

Yes, indeed. What the Boleyn family did essentially, was that they married into land. And, arguably, the whole story of the family dynasty is driven by women, because it’s through the female line that the Boleyns came into a series of massive houses. These aren’t small places; these are really big double or, in some cases, triple courtyard houses. Obviously, they’re not as big as Hampton Court but they are very, very substantial residences.

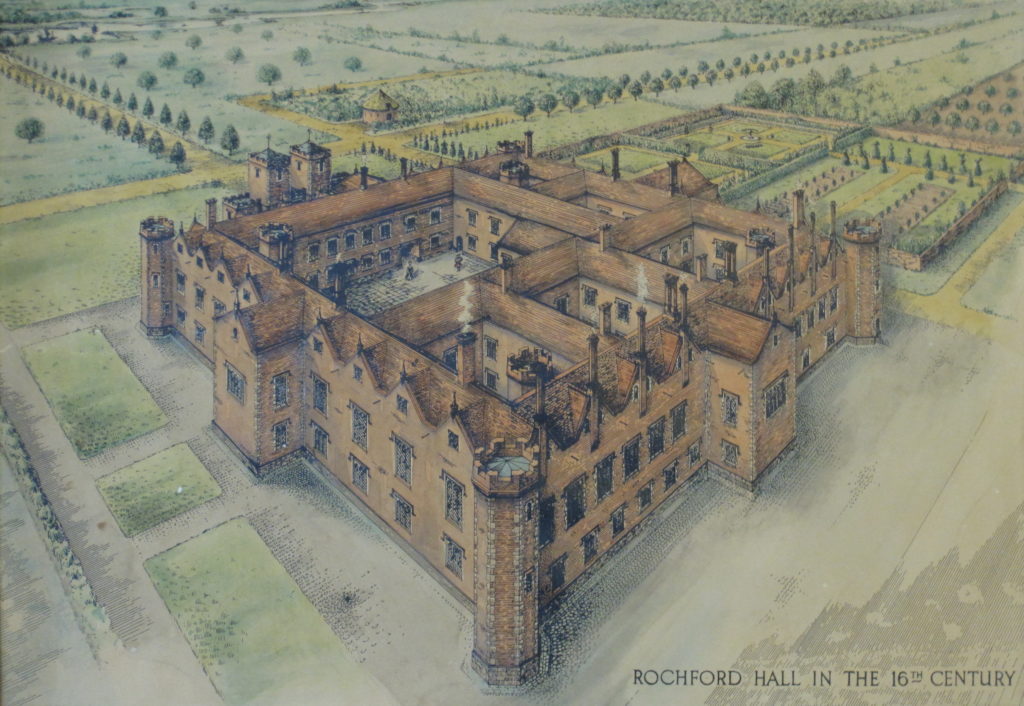

Rochford Hall, which is in Essex, still has big chunks surviving. The remains of the building are now on a golf course. It’s very, very close to the church and the church has a private pew in it, which I think may well have been a private pew that the Boleyn family, including Anne, would have used. So, you can get a little bit of a flavour of the size and splendour of the house and its landscape setting because, of course, although it wasn’t surrounded by a golf course in the sixteenth-century it was surrounded by beautiful, mature trees in parkland. The golf course still allows you to get a sense of that.

Now, with regard to what is left of Luton Hoo; there’s nothing, absolutely nothing! It’s very, very frustrating. The Hoo, as it was known, was another big house with a lot of land attached to it. However, in the seventeenth and eighteenth-centuries, and again in the nineteenth-century, a succession of very big building projects literally scalped the landscape clean. This is very frustrating because it’s quite clear that Thomas Boleyn, Anne’s father, spent a lot of time there; it was one of his principal residences.

Sarah:

I knew something of Rochford Hall and the likes of Blickling Hall, but I didn’t really know so much about Luton Hoo so, after listening to your lecture, I went away to try and research it a bit more. There doesn’t even seem to be any description of what the house actually looked like, is that right?

Simon:

Yes, that is right although that doesn’t mean that it isn’t there. I think that it is quite possible that more could be found out and it’s also perfectly possible that more could be found out about Rochford Hall, as well. It might even be possible there to partially reconstruct what it was like in the Boleyn period. I doubt that you could get that far with the Hoo, but I think it is possible to get further. I did look at quite a lot of primary documentation, including all the relevant wills and inquisitions post-mortem, but I suspect with a really sustained campaign, you might be able to get further than I did.

Sarah:

Thinking about the trio of properties we’ve already been talking about (Hever, Luton Hoo and Rochford Hall), I was left with the impression that Hever perhaps wasn’t used so much as a family home during the Boleyn children’s childhood. No doubt it was used, but I’d always thought that was the principal residence in which the children grew up. Would it be more accurate though to imagine that they would have moved equally between those three or four properties, or more?

Simon:

Yes, you’re quite right. Hever is very, very small and I was able to reconstruct in great detail the plan of the house in the time that it was owned by the Boleyns. It is a very, very small house and Thomas Boleyn was a very, very great man and there’s no way that his whole family (and there were a lot of children, plus all their servants and attendants), could have stayed there for any serious length of time.

There was very good hunting in the High Weald and I think it was very much used as a hunting lodge but also, and this is absolutely crucial to understanding it, it was close to Greenwich. In the early part of Henry VIII’s reign, when the fatal attraction between Henry and Anne began, Greenwich was the headquarters of the monarchy and it’s a very straightforward ride from Greenwich to Hever. So, there were a lot of reasons why Hever was geographically very convenient and, during that period, when Anne really had to keep out of the way because it was all very difficult, it was the ideal place to retreat to because there were hardly any servants there; it was a very, very private location, surrounded by a double moat in the middle of a hunting park. If you didn’t want people to bother you it was the obvious place to go.

Sarah:

That’s really interesting; it sheds a whole new light on the subject. And I guess the closeness to Greenwich would perhaps explain why she retreated there when she fell ill with the Sweat. I think they were at Greenwich when they were when the king first received news of the outbreak in London. Now I’m also curious about the Boleyn properties in London. I know that Anne occupied certain properties, I think Durham House was one when she was in her ascendancy, but do we know of any specific London properties like, for example, we know of Austin Friars for Thomas Cromwell?

Simon:

We do know where their houses were in the City of London. We know that and, in fact, one of the consequences of me giving my Gresham lecture on the Boleyns is that someone who is making a study of various aspects of this got in touch with me. She has managed to identify a Boleyn property in the City that I hadn’t found. So, there were a number of houses in the City but, of course, by that stage, these big aristocrats were moving West. They were moving out of the city and colonizing swanky residential areas, such as The Strand. We should also remember that Thomas and Elizabeth had lodgings in every single royal place, indeed quite extensive lodgings in some of them. So they were well provided for in London.

Sarah:

Do we know exactly where the Boleyn properties in London properties were?

Simon:

Well, for example, at one point there was a house near Lincoln’s Inn and at another time there was a house in Old Jewry, right in the centre of the City. These were probably pretty substantial masonry houses, but no house in the City was very big because it was very constrained space. The occupants would have spent most of the time at court and the moment that the ‘end of term’ came they’d be out of London. In the case of the Boleyns, this would have meant going to the larger houses, to Rochford or Hoo, in particular, and then also little trips to Hever to entertain themselves.

Sarah:

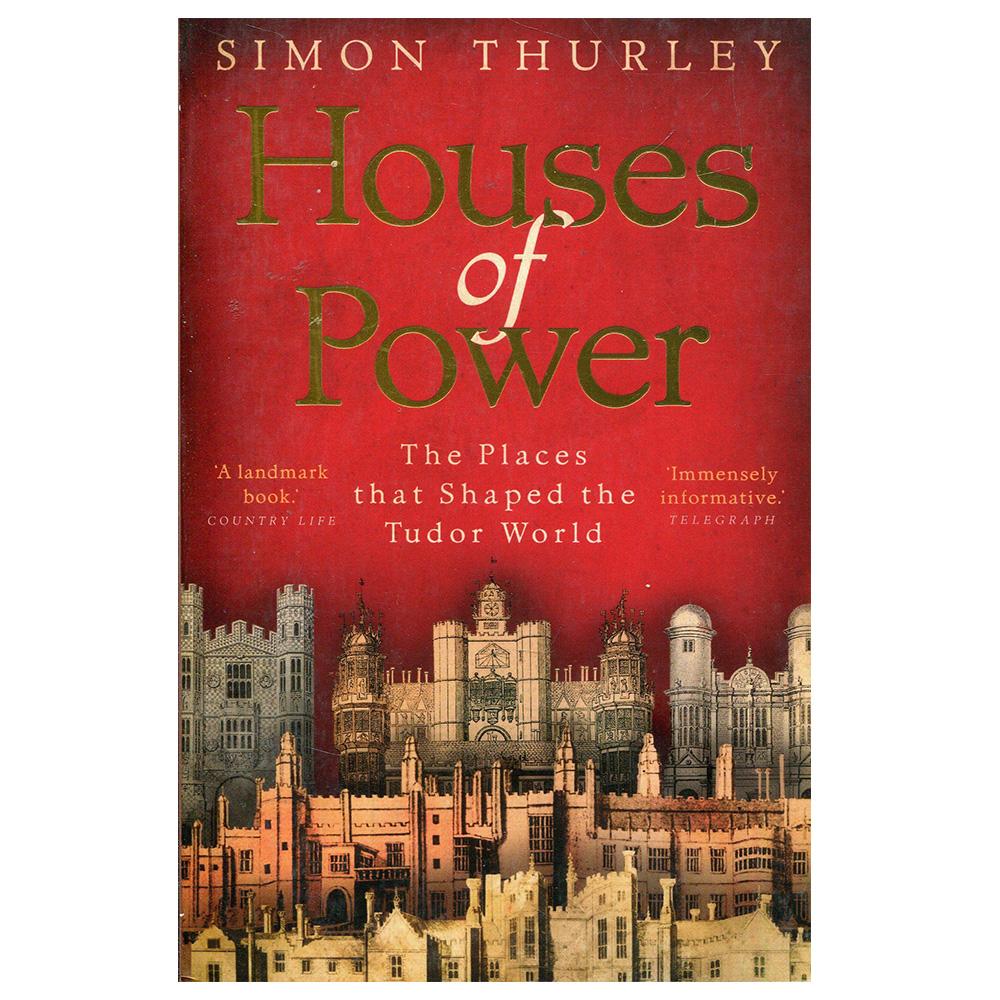

Great, I’m looking forward to it! Now, I want to talk now about your book ‘Houses of Power’. What an absolutely amazing book it is! It’s so packed with illuminating detail. I keep going back to it, having forgotten what I’ve read and going, “Oh my goodness!” all over again. Please can you tell us about what stimulated you to write it and if somebody was buying it, what could they expect?

Simon:

Well, I’m really someone who writes history through buildings and through places and this book is about buildings, but it is also about places. It’s about urban space and it’s about the countryside as well as individual buildings. It’s really trying to help us understand the Tudor court through the places in which it spent its time. Obviously, there is a considerable amount of information on Whitehall and the Thames Valley houses. This is where the court resided in the wintertime: Greenwich and Richmond etc. However, there’s also quite a lot about what happened elsewhere, including the progresses of Henry VIII and Elizabeth. The book also explores how those progresses worked; where they went; the houses they stayed in and what happened if you were unfortunate enough to be an aristocrat and Queen Elizabeth turned up on your doorstep!

Henry VII’s Houses of Power

Sarah:

When you wrote the book, were you collating all the knowledge you’d already acquired over the years or were you trying to research something else? And also, my second question, if I may, is did you learn anything through writing ‘Houses of Power’?

Simon:

‘Houses Of Power’ really came out of my very first book, that was published in 1993, and which was called ‘The Royal Palaces of Tudor England’ and that was essentially my PhD. That book had a number of flaws. The two principal flaws were, firstly, that back in 1993, I hadn’t really properly understood Henry VII and, secondly, that the book didn’t go on to explore the residences of Edward, Mary and Elizabeth. Both of those shortcomings made quite a big difference to the sort of the picture I was able to paint; particularly in relation to not really fully understanding Henry VII.

So by the time I started writing ‘Houses of Power,’ I thought I knew everything about the subject. Then, I found to my complete horror that I really didn’t and I had got it quite muddled up and misunderstood. And so certainly the material on Henry VII is very original; I don’t think anybody previously understood the interrelationship between Henry VII and the places in which he lived. I think that is a very new insight. Also, the Elizabethan stuff; by that, I mean properly understanding Queen Elizabeth I’s attitudes to architecture and to the places in which she lived and how she used them. Everyone says she wasn’t interested in building, but actually, she built some pretty important things. So, I think the book did surprise me. Having worked in this area for more than 30 years, I realised how much I really didn’t know and didn’t understand. I felt that it was very important to try to get it all together in one place as a coherent narrative.

Sarah:

I was really fascinated by what you were saying there about Henry VII. Can you talk a little bit more about that; about what you learned about him and the places he occupied and what that reveals about him?

Simon:

I think the single most important thing that one has to remember is that it’s been very, very unusual in English history for a monarch to come to the throne who had really never stepped inside a royal palace before he became King. On one occasion, for a matter of hours, Henry VII came to London, went into Westminster Palace, saw King Henry VI and that was it.

So, when he became King, every single royal house he went into was completely new to him. He had been in Westminster as a teenager 20 years before he came to the throne, but he’d never been to Windsor; he’d never been to Woodstock; he’d never been to any of the big palaces. So there’s a real sense of a reinvention that takes place and that reinvention can only really take place when he feels a bit more secure on the throne.

For the first part of his reign, he’s looking over his shoulder in every direction for rebellions. He could have lost the throne at any moment. But the moment he feels secure on the throne, after about 1500, you do see him taking a completely different course. He’s able to reinvent things in his own image. There is a sense then that Henry VII starts afresh. One of the reasons he can do that is that he’s not encumbered by a huge back history of tradition, because he didn’t know what it was like being at court before he got there.

Sarah:

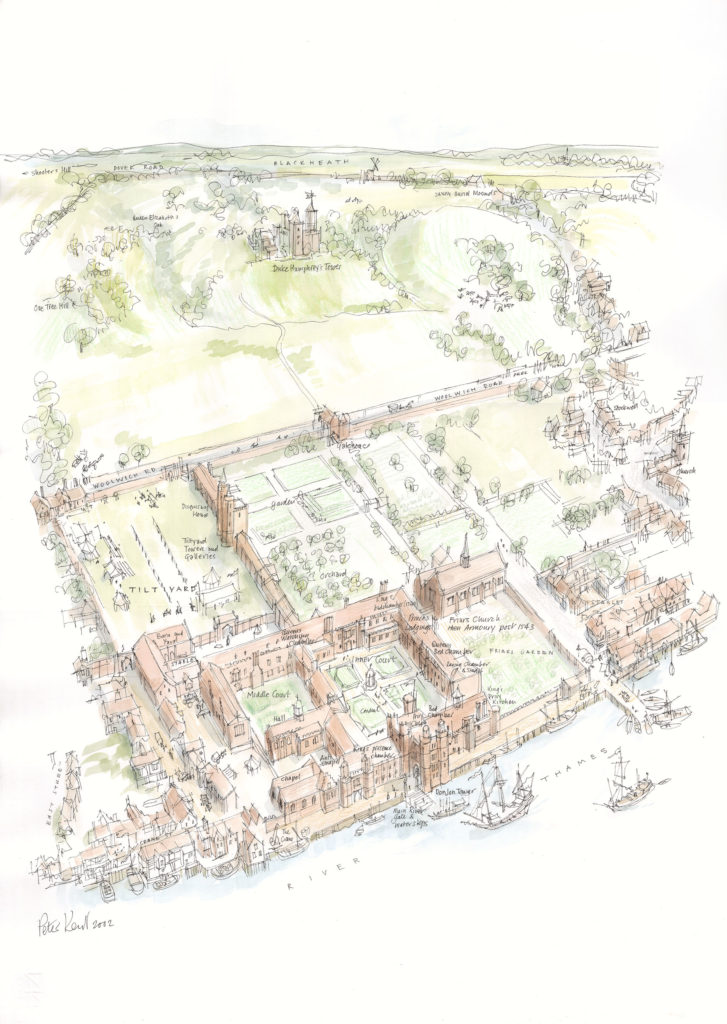

Do you think that reinvention you’ve referred to was evident in his development or rebuilding of what was the Palace of Placentia, Duke Humphrey’s old palace, which became Greenwich? Was that his first major building project, and can that building at Greenwich tell us anything more about his aspirations, tastes and so on?

Simon:

Yes, I think it definitely can. Placentia or Greenwich (depending on what you want to call it, it’s called different things at different times) is a very particular type of palace because it is one that has a physical division between a sort of pleasure area and a more public area. I think what’s very important about Henry VII is that he’s involved in a break with tradition, whereby he more or less insists on having a private and safe environment after he discovers a plot in which his Lord Chamberlain and his Lord Steward are implicated. It’s pretty horrific. He is determined to create an environment within the royal houses where he could be safe and secure and that leads to the whole new concept of private residences within these places.

Sarah:

That’s very interesting! Now, one of the aspects on which I completely resonate with you is my love of seeing history through places. What I have found out is that when I understand more about a Tudor building, I understand more about the history and the events and the people that lived there. I know you share that feeling; can help me explain why that might be the case?

Simon:

Well, imagine you’re thinking about the Reformation and you live in Bolivia (assuming anyone in Bolivia is remotely interested in English history) and you’re reading textbooks. You can appreciate that there was a big moment that happened in English history. Then imagine that you get on an aeroplane and you go to Fountains Abbey and you see this huge magnificent building of stone for yourself. You begin to understand the investment in bricks and mortar and money that went into the whole of monasticism. Then you begin to understand that there were reasons why the monastic life was not fulfilling its original purposes; that there was corruption and there were abuses; that there was a process of reform and a greedy king who wanted to liquidise its assets for himself.

That visit to Fountains Abbey will tell you an awful lot more than reading four or five books because you’re actually there and you can see the physical impact. You can replicate that with the Tudor world; you can visit the Tower of London or Hampton Court – there are all sorts of places you can go to – and suddenly you begin to get it. I think that’s it – you step into a place where you can touch the very brick that was touched by the people you are reading about and studying. Obviously, things will have changed, but without going to a place it’s very hard to understand.

When I write about places I never ever write about them unless I have been there and really properly studied the place as much as I can in its physical sense. When writing ‘Houses of Power’, I had visited them all before, but I went back to dozens and dozens of places to look at them again to make sure I was really understanding their landscapes and setting; how the parks related to the houses; where the rivers were; where the roads were; how you’d get to them – all of that you need to get your teeth into.

Sarah:

I know it’s a bit of a clichéd phrase, but it absolutely does bring it all to life when you can understand how people would have arrived at the place and how they would have used the rooms. Anybody that follows this show will recognise the expression that I use with my co-author of the ‘In The Footsteps’ books, Natalie Grueninger; that is that ‘it is that it’s only time and not space that separates you’ when you visit a historic site. I think that’s exactly what you’re referring to there about being able to touch the bricks – and that’s very special.

Simon:

Yes, very neatly put.

Simon’s Top Tudor Places

Sarah:

Sadly, we’re coming towards the end of our chat. I have a couple of slightly whimsical questions for you now, if I may, Simon. First, of all the places you have studied over the years, is there a particular place, house or chamber from the Tudor period that you would love to see recreated in all its former glory and why would you choose that one?

Simon:

There is one building that I’ve researched more than anywhere else and really thought about more than anyone else and gone back and back and back to – and that is Whitehall. Whitehall is really such an important and influential building and, despite all my efforts over 30 years, it is still fundamentally misunderstood. People call it a jumble of buildings, a pile of disorganised structures hurled together – but that simply isn’t the case.

Whitehall is really such an important place; to understand how it worked explains how politics worked and how the government worked at the time. So, if I could have my day in the past, unquestionably I would want to spend it in Whitehall. Incidentally, I was reading seventeenth-century diarist, Robert Hook, the other day and was fascinated to learn that Christopher Wren apparently played exactly the same game in the 1670s, asking where would you go back to if you could go back in history. So, it’s an old game, but it’s a really nice one, isn’t it?

Sarah:

It is. For me, it would have to be the Royal Apartments at The Tower, simply because Anne Boleyn is my historical heroine, as many listeners will know. To be close to the place where she saw her moments both of triumph, and of tragedy, would be incredible. Anyway, enough about me and my whims! My next whimsical question is: if there is one so far unanswered question about Tudor houses of power, to which you would really love to have the answer, what would it be?

Simon:

Well, there are a number of very important houses of power about which we still don’t know as much as we want to. There are some quite specific things I’d like to know. For example, I would love to do a bit more digging at Greenwich. If someone were to say ‘Okay, you can do a really massive archaeological dig at Greenwich’. That would be great. The lawns are all there ready and just waiting for my spade! I think the question I’d want to answer would be about the inner court there, which Elizabeth I remodelled. I’d really love to see if I could find some big chunks of stucco or terracotta to understand exactly how classicizing that courtyard was. I think it was rather an amazing courtyard and because it is lost to history, people believe that Elizabeth I didn’t do anything, but I think that she did something there that was pretty amazing and we just don’t really know about it.

Sarah:

Well, my final question is about up and coming projects. I’ve mentioned, of course, your Gresham lecture coming up on the Cecils that everybody should make a beeline for. Are there any other projects you can tell us about?

Simon:

I’m in the process of completing a sequel to my ‘Houses of Power’ book which, you’ll be disappointed to hear, is about the seventeenth-century and the Stuarts. So, I can’t really mention that in this environment! But I do actually have a project about Tudor merchants’ houses in the City, which will see the light of day as a book in due course. I think that will be interesting and revealing for people because only one of them survives and that is Crosby Hall, which is now in Chelsea, and which was owned by Thomas More. That will be the centrepiece of the book.

Sarah:

That sounds marvellous, I can’t wait! In the meantime, I just wanted to thank you so much for taking the time out and talking to us today about these wonderful houses of power.

Simon:

You are welcome! It was really nice to talk to you.