Hever Castle: Tudor Day Trips From London.

Nestled amidst the picturesque countryside of Kent, Hever Castle is an enchanting building with its moat, turrets and Tudor-style architecture. Surrounded by lush gardens and the tranquil Kentish landscape, Hever was famously the childhood home of Anne Boleyn. Here, she received her early education under the watchful eye of her mother, Elizabeth Boleyn, and grandmother, Margaret Butler.

Today, much of what you see is the result of William Waldorf Astor’s remarkable efforts to save a long-neglected building; he used his fortune to restore and extend the castle in the early twentieth century.

In this mini ‘day-out’ guide, we will touch on the castle’s Tudor history, tour the Boleyn home, and cover some essential visitor information. This blog includes updated information regarding some of the very latest discoveries relating to the social and architectural history of the Boleyns’ erstwhile home. So, let’s go!

Hever Castle: Essential Travel Information

Travel:

- By Train from London Bridge to Hever Station – direct.

- By Car, around 2 hours from central London.

- Journey Time: 50 mins.

- Travelling from the Station to Castle: Hever Station is unmanned, and there is no taxi rank on site. So, if you want to travel to the castle from the train station, you must book a taxi before your arrival. However, walking to the castle, which is around one mile away across the pleasant Kentish countryside, is also possible. Here is a map of the walk from the station.

Introduction to Hever Castle

‘Remember me when you do pray, that hope doth spring from day to day.’

Anne Boleyn

For anyone who loves Anne Boleyn, Hever Castle in the heart of ‘England’s Garden’ of Kent is a natural place of pilgrimage. As the name suggests, it is located in the village of Hever and began as a country house, built in the thirteenth century. From 1462 to 1539, it was the seat of the Boleyn family.

Sir Thomas Boleyn inherited the property upon his father’s death in 1505. Subsequently, he redeveloped the somewhat outdated, moated medieval castle into a fine, contemporary English manor house fit for an aspiring courtier.

Anne spent much of her childhood at Hever before being sent to the Netherlands in 1513 to receive an education at the court of the Archduchess Margaret of Austria. Later, during the early days of Anne’s romance with Henry VIII, she would again spend time at the castle, including a long sojourn there over the winter of 1527/8.

During this time, in February 1528, Anne received Drs Edward Foxe and Stephen Gardiner on their way to visit the Pope in exile; their embassy from the King was to obtain a decretal commission from the Pope to allow the royal divorce case to be heard in England.

Anne returned to the family home in June of the same year. During that fateful summer, the Sweat returned to England, forcing Henry to flee to Waltham Abbey while Anne sought refuge at Hever. She was probably at Hever with her mother and father, as Thomas and Anne subsequently fell ill there in late June/July. Fortunately, both fully recovered, and Anne returned to court sometime in early December 1528.

Touring Hever Castle: Rediscovering Its Lost Past.

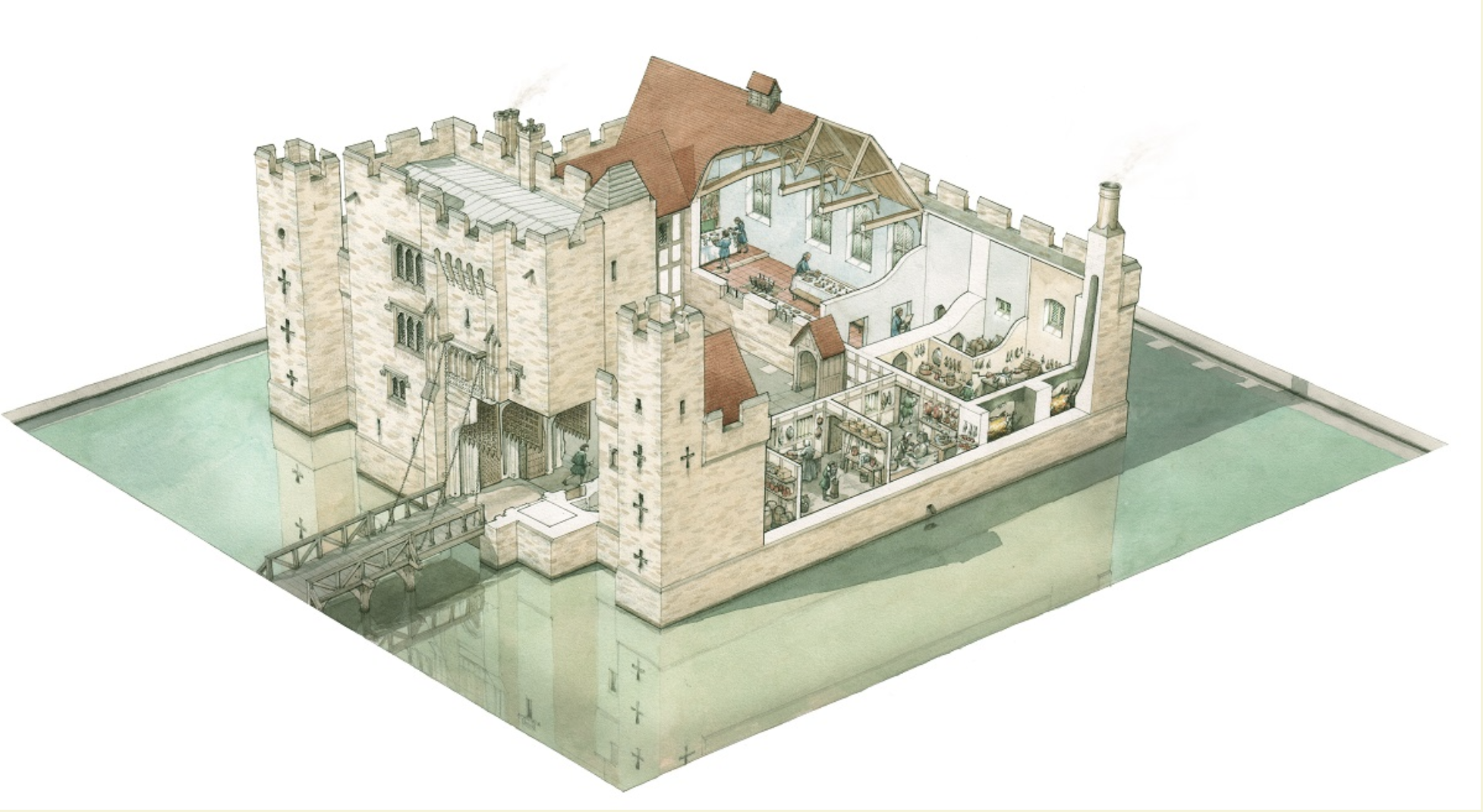

This quintessential fortified medieval manor house, nestled in the bottom of an idyllic, gently sloping valley, is utterly beguiling and instantly catches your heart. The setting makes the picture-perfect English postcard: sculpted lawns with pretty lily-covered moats. All around you, immaculately tended flower and herb gardens abound. However, do not be fooled by modern-day appearances. If you want to get a feel for how the castle looked in Anne’s day, you have to think rather differently about it.

The first thing you would see as you approach the castle is just how different the setting is. It was much wilder and more rugged than today’s cultivated gardens. The original Norman castle was constructed in the classic motte-and-bailey design, with a central timber-framed hall defended by a surrounding ditch and palisade. Later, a stone gatehouse was erected, which endures in its original form.

Directly opposite the gatehouse were the stables. These were contemporary to the Boleyns’ time at Hever and possibly pre-date it. The building was an extensive, timber-framed construction. Recent research undertaken by Dr Owen Emmerson has clarified that the building not only contained stables but had a vaulted hall with a crown post roof and five bedchambers. Thus, it was a substantial structure that can be seen in the old photograph shown below. Sadly, the structure survived into the 1890s but was demolished by the then tenant/owner of Hever, Guy Seabright, much to the chagrin of The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings.

While we are discussing Mr Seabright’s actions, I should mention that he was also responsible for tearing down the outer gatehouse, which once existed where the current visitor information hut is today, just outside the second moat.

Nearby, to the west of the castle, was the original village of Hever, consisting of a scattering of modest dwellings. Lord Astor had the entire village moved to its current position in the early twentieth century to allow the family greater privacy.

In the sixteenth century, the area in front of the building was covered in boggy marshland, and the castle was surrounded by dense forest. In Norman times, this forest was named Andredswald, which roughly translated means ‘the woodland where no man dwells’. Even the King’s map makers of medieval England knew of its reputation as notoriously lawless and dared not enter it.

Image one: A reconstruction of Hever Castle, showing an interior cross-section of the house;

Image two: Hever Castle by Edmund John Niemann, painted in 1858. Notice how the castle is surrounded by dense forest, with a marshy area in front of the gatehouse.

Images courtesy of Hever Castle & Gardens.

Rather than the picturesque double moat that we see today, during the Tudor period, the front entrance to the castle was guarded only by a single moat, which was traversed by a stone bridge. The main body of the castle consisted of only two floors; William Astor added the third floor. However, the gatehouse has remained unchanged since it was built in the thirteenth century.

If the setting of Hever Castle is much changed, then too is its interior, which in Anne’s day would have been far less elaborate. The wealthy Astor family last extensively renovated the building in the early twentieth century. As a result, many of its rooms are now sumptuously clad in oak panelling; the staircase and minstrels’ gallery in the Great Hall is panelled with wooden interiors, intricately carved in the grotesque style so popular in Henry VIII’s palaces; the ceilings are ornately moulded in traditional designs; the rooms stuffed full of beautiful antiques, although not all contemporary to the sixteenth century.

Finally, its collection of Tudor portraits makes for a ‘Who’s Who’ of the Tudor court and has been described as second only to that of the National Portrait Gallery in London. As you wander around this charming little home, it is not hard to imagine Sir Thomas or Lady Elizabeth, or indeed any of the Boleyn children, moving about its rooms, perhaps even receiving the King of England as he visited Hever in passionate pursuit of Anne (although whether Henry visited Hever at all is currently a point of contention as no direct evidence of this has been found in recent research).

Regardless, there is a serenity about the castle, and it sucks you in, leaving space for the walls to whisper their secrets to you.

Now, let’s examine each room in turn and try to reimagine it as it would have been in the sixteenth century.

The Great Hall at Hever Castle

The Great Hall was a public space, and like all great halls of the time, its utility began to change in the sixteenth century. In the early medieval period, communal living was the norm, centring on the Great Hall. By the sixteenth century, well-to-do Tudor families increasingly used private spaces to pass the time, dine en famille or with honoured guests. Therefore, at Hever, the hall, which was the centre of the home, would most likely have been used by the Boleyns for dining and entertaining only on high days and holidays.

At the top of the hall would have stood a dais, upon which rested a grand table. During the day, when Thomas Boleyn was at home, he may have spent some of his time working there and attending to the family’s business. This place is also reserved for the Lord, his family and guests to eat. There would have been no fancy tapestries or fine oak panelling in the Great Hall. Instead, the walls were covered in plain, light-coloured plaster and simple terracotta floor tiles. The fireplace had no ornate stone carving; it would have been fashioned into the simple shape of the iconic Tudor arch that we now associate with the period. Also, there was no ornate minstrels’ gallery dominating the modern room. As a result, the hall would have looked much plainer and more open than we see it today.

Another feature that has greatly changed is the castle’s arrangement of windows. Initially, and certainly, when the Boleyns first took up residence, there were no large windows on any of the exterior walls of the castle. This was an early, defensive, medieval feature. Instead, the Great Hall would have been lit by windows on the south wall, which faced into the courtyard.

These south-facing windows were lost when the ground-floor gallery and staircase gallery were added during the mid-sixteenth century. However, as the threat of civil war declined through the early sixteenth century, so did the need for a castle’s defensive features. This, alongside the growing wealth of the Boleyns, allowed the family to make changes to remodel the castle and make it more contemporary and comfortable as a luxurious family residence. It is believed that it was at this time that Thomas Boleyn had the large windows, which now light the hall from the north, inserted.

The Inner Hall and Sitting Room

In Anne’s day, this hallway sumptuously decorated hallway (attributable to the Astors) did not exist. Instead, the kitchen and pantry occupied this part of the castle.

The sixteenth-century kitchens were double-height, and when in use, the two large fireplaces set against the east wall (where the current fireplace is located) would have made this room one of the warmest in the house. Sadly, the chimney stack that once served these fires is no more; it collapsed in the nineteenth century when the kitchens were no longer used.

Directly off the kitchen on the ground floor were two other domestic spaces used to service the needs of the family: the larder and the dairy. Sited on the castle’s east side, these rooms were cooler than their counterparts in the building’s west, or family, range. These rooms; the kitchen, pantry, dairy and larder were the domain of the Boleyn’s household staff; a now-lost vice-stair, inserted by the Boleyns, allowed the household staff to pass between these rooms on the ground floor and those on the first floor (where servants slept), without disturbing the family.

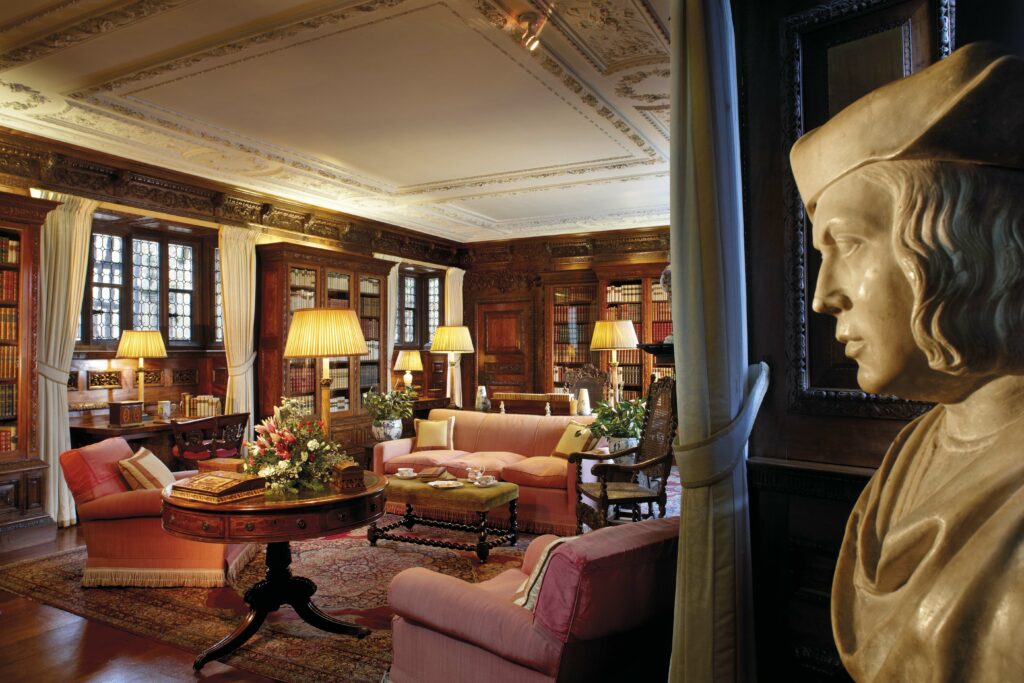

The Library and the Parlour

The side of the castle, the west wing, contained the family’s private rooms. Today, the ground floor is occupied by the elegant library created by W.W. Astor; its walls are crammed with precious books in fine oak cases. However, this wing of the Boleyn family home was not always so grand. Nor is it likely that an extensive library existed; books were far too rare and precious, and such libraries were probably the preserve of only the King, the most high-status nobles and great religious houses.

Instead, the library and the room beyond that, which is not (yet) open to the public, would have formed the central administrative, or châtelaine’s, office where Elizabeth Boleyn would have run the estate in her husband’s absence.

The retiring room, or parlour, was the principal private reception room for the family in Anne’s time. It was created by the Boleyns by partitioning off the westernmost end of the original Great Hall. A now-lost door would have connected the two. The creation of this parlour speaks to a desire in the Tudor upper classes for increasing privacy. It served as a ‘withdrawing’ place for Thomas Boleyn and his family. As a guest, you would be entertained by a roaring fire in the winter or offered a drink to quench your thirst in the summer.

The Staircase and Staircase Gallery

Another major difference in the castle’s layout between the sixteenth century and today is the position of the main staircase leading to the upper floors. Many changes have been made over time to the castle’s principal family staircase, stretching from the castle’s inception in the fourteenth century to Astor’s refurbishment of Hever at the turn of the twentieth century.

The family staircase originated in the west wing, next to the châtelaine’s office. This steep flight of stairs pre-dated the Boleyns’ time at Hever and probably dated to around the 1380s when the castle was first built. After the Boleyns moved to Hever in 1505, they added the stone vice-stair that connected the parlour with a room that today we know as ‘Anne Boleyn’s Bedroom‘, keeping the 200-year-old principal staircase intact in the west wing.

The next major redevelopment occurred in the mid-sixteenth century when Anne of Cleves made Hever her main home (having lost the Palaces of Richmond and Bletchingley). Anne had the lower and upper (or Staircase Gallery) inserted, connecting directly and, for the first time, the east and west wings of the castle. At this point, she had a staircase inserted just to the left of the current main entrance.

This remained the principal staircase until around 1830, when the then owner/tenant, Jane Waldo, removed it and placed it almost directly opposite but slightly to the right of the main entrance. Finally, W.W. Astor demolished it, rearranging the staircase so that it originated in the inner hall where you see it today. That’s a lot of change!

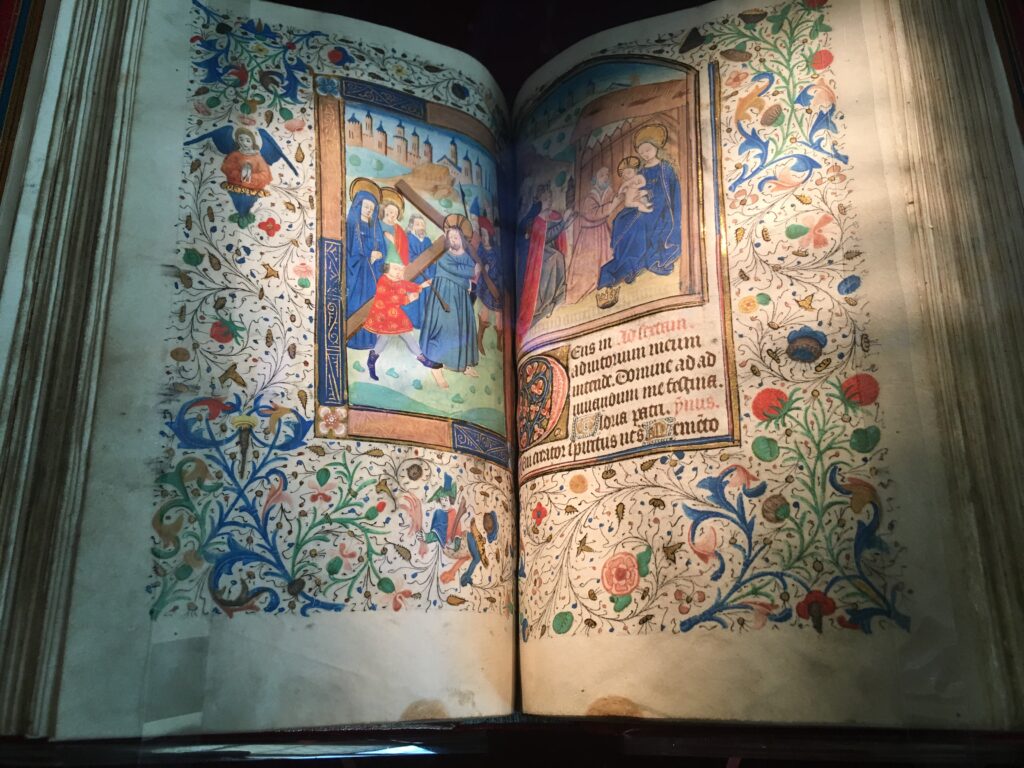

Anne Boleyn’s Bedroom and the Book of Hours Room

Yet again, this part of the castle looked entirely different from how we have come to know it in modern-day life. In the twenty-first century, it is divided into distinct and separate rooms: Anne Boleyn’s bedroom in the northwest, a large room which houses two of Anne’s prayer books (The Book of Hours’ Room), and finally, overlooking the moat to the south, a bedroom containing numerous fine Tudor portraits.

When I first began writing about Hever, there was a distinct lack of clarity about how exactly this space was arranged and used. However, Owen Emmerson and the team at Hever’s more recent and extensive research on the social and architectural history of the castle has shed a considerable amount of light on the subject, greatly expanding our understanding of how this west wing was used.

A stone vice-stair led up from the parlour; this disgorged itself into an antechamber (now Anne Boleyn’s Bedroom). During the Boleyn’s time at the castle, this room had a peephole in one wall, allowing the family to look down on the goings-on in the hall below. The sequence of rooms on this floor was collectively known as a ‘Solar’. This was the main family room, comprising the aforementioned ante-chamber, the head of the Great Stair, the Great Chamber (the large, central chamber which today is The Book of Hours Room) and the best bedroom beyond.

In this privy space, the family would relax, dine privately, read, discuss matters of the day and sleep. Indeed, many private and sensitive conversations must have occurred here! At the far (south) side of the solar, a doorway opened into the best bedchamber; this is where Thomas and Elizabeth Boleyn would have slept apart from the children. If you are wondering where exactly Anne and her siblings would have slept, they would most likely have bedded down together somewhere in the Great Chamber.

The Staircase Gallery

On the first floor, you will find the magnificent Staircase Gallery, now thought to have been an addition made by Anne of Cleves when she was in residence in the 1550s (and not commissioned by Thomas Boleyn, as has been previously thought). It was created to connect both wings of the house on the first floor and also with the newly created long gallery upstairs. At the time, it would have undoubtedly been the epitome of sixteenth-century fashion.

As noted previously, when this structure was inserted, the head of the principal stair led into this gallery at the first-floor level, hence its name, ‘The Staircase Gallery‘.

The Waldegrave Room and the Henry VIII Room

When the Boleyns occupied Hever, the rooms in the castle’s east wing were used by servants and never by the family. In truth, the magnificent Henry VIII Bedroom, which currently occupies part of this wing, is sadly only named in honour of the King; it is unlikely that he ever used this room. In fact, despite the popular Victorian myth, which has been replicated in many Hollywood movies, there is no definitive evidence that Henry VIII ever visited Hever (Thanks to Owen Emmerson, who is currently researching Hever’s entire social history, for sharing this with me). This does not mean that we can say he didn’t visit Anne at Hever, but just that there is no direct evidence for it.

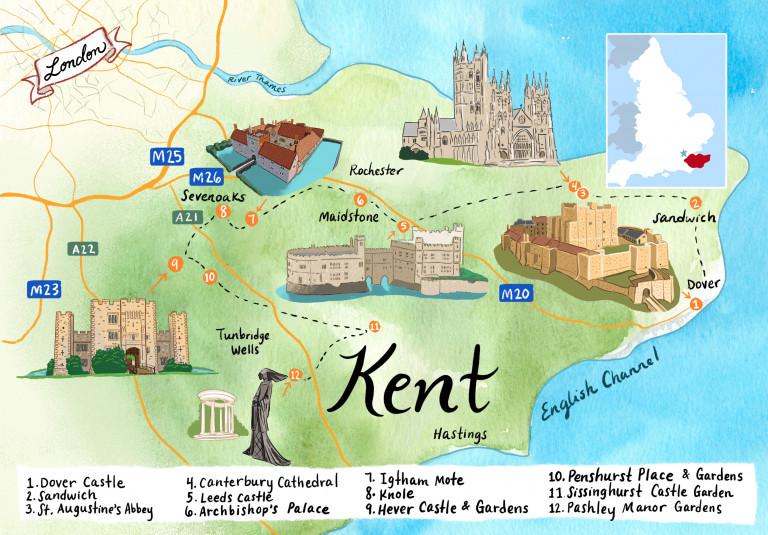

However, IF Henry had ever pitched up at the Boleyn’s front door, it would most likely have been during a day’s hunting while based at the King’s own manor of Penshurst. Penshurst Place, lying just 3-4 miles away, would have been within easy reach of Hever when the King and his entourage were staying in residence; a day trip with a discreet hunting party in tow, comprising some of the King’s most trusted friends and courtiers, would have been entirely possible.

The Long Gallery at Hever Castle

This is another space that was long thought to have been a Boleyn creation. Thanks to research by Dr Simon Thurley, it has now been attributed to Anne of Cleves, who lived at the castle after her divorce from the King and after her manors of Ricahmond and Blethcingley had been forcibly removed by Edward VI’s council. Anne commissioned the gallery as part of the renovations undertaken at Hever to make it a more comfortable and stylish dwelling.

The gallery was created by putting a ceiling over the Great Hall below. Once again, the sixteenth-century gallery appeared much simpler than the sumptuously wainscoted room we see today. However, there would have been a pretty, decorative ceiling stuccoed with foliage. Of course, the long gallery served several purposes; many pieces of art could be displayed along its walls, while its size provided the perfect space to exercise when the weather forced Hever’s residents indoors. The Tudors tended to live outdoors, coming in only to shelter in the foulest weather, to eat, sleep, or entertain guests.

Footnote: Much has been done in the last few years to extend our understanding of the social and architectural history of Hever, the former led, in particular, by Dr Owen Emmerson, while for the latter information on the Staircase and Long Gallery, we can thank Professor Simon Thurley and his team.

Since I first researched and wrote about the castle for In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn over ten years ago, it has been fascinating to watch these new discoveries being made and how our understanding of the castle’s history has evolved. I am grateful to both these scholars for their outstanding contributions to the Boleyn story and that of their most famous residents.

Visitor Information: If you plan a visit, it is always wise to check out the Hever Castle website for all the latest visitor information.

Sources and Book of Interest:

The Boleyns of Hever Castle by Owen Emmerson and Claire Ridgway.

Houses of Power, by Simon Thurley.

Other Tudor places to visit nearby:

Of all the counties in England, Kent has many Tudor riches to enjoy – find them here in my Kent itinerary.