Austin Friars: Cromwell’s City Power House

Thomas Cromwell is one of the most interesting, complex and reviled characters in Tudor history, mainly because of his seemingly ruthless destruction of the Boleyn faction in May 1536. Despite his character flaws, his genius and astonishing talents are as apparent now as they were to the two men who would spot, nurture and reward them at the time: Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and, later, his master, King Henry VIII. During Thomas’ rise to power, through the 1520s until his downfall in 1540, Cromwell based himself in the north of the City of London in a tenement belonging to the religious order of the Augustine Friars, often referred to as ‘Austin Friars’.

Note: There is a podcast to accompany this blog. To learn more about Cromwell’s life, read on to the end of this blog for links to the episode in question.

In this blog, we will get a wonderful glimpse into Thomas Cromwell’s private life by recreating what is known about his London home, which became one of the largest and most palatial private residences in the City. But before we reimagine the building, let’s look at the Austin Friars complex and pinpoint exactly where this rising star of the Tudor court took up residence.

A Brief History of the Austin Friars of London

The Augustine Friars first set up their base in London in the 1260s, in an area to the north of the City, just inside the city’s walls. Over time, the new friars (of which there were around 60 at the Friary’s peak in the fourteenth century) built a grand church notable for its lofty steeple. According to Nick Holder, who has written extensively about the lost friaries of London, this distinctive building became both a ‘physical and spiritual landmark’ in the area for the next 200-300 years until its destruction at the Dissolution. Interestingly, John Stow notes in his Survey of London that Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, who was beheaded on the orders of Henry VIII in 1521, was laid to rest in this very church.

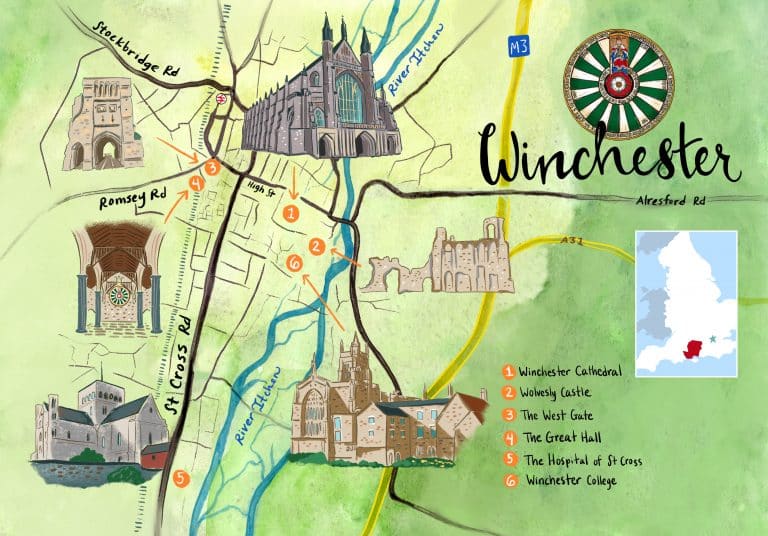

Like any religious foundation of the day, the Austin Friars’ precinct was demarcated by a boundary wall to provide the Friary with privacy and security. At its zenith, the precinct covered an area that extended over five-and-a-half acres and was accessed via one of four gates, which were sited in the boundary wall to the north, south, east and west of the friary church. However, the main gate was on the south side of the precinct, fronting onto Throgmorton Street, close to the junction with Broad Street. It was 12 feet wide and directly entered the Friary’s churchyard.

Also, like other religious houses of the day, the Friary rented out some of the peripheral buildings it owned as tenements to laypeople of the city. You will recognise many notable figures of the Tudor court listed on the roll call of tenants, each occupying various tenements at one point or another during the first half of the sixteenth century: Erasmus (who, Nick Holder notes, left without paying the bill!), Eustace Chapuys, Richard Rich, Thomas Paulet (brother to courtier William Paulet, later 1st Marquess of Winchester), Thomas Cawarden (Master of the Revels) and, of course, a certain Thomas Cromwell.

Clearly, this part of London was very cosmopolitan. It was populated particularly by Italian merchants, such as John (Giovanni) Cavalcanti, who would initially be Cromwell’s neighbour at Austin Friars (before Cromwell later bought up that property as part of the extensive expansion of his London home in the 1530s).

To understand why this area of London was particularly attractive to Cromwell, we would do well to bear a couple of things in mind. Firstly, as a younger man, Thomas had spent a considerable amount of time in mainland Europe, including a stint in Italy. During his time in that country, he lived for a period in Florence, immersed in the epicentre of the European Renaissance. You might argue that it was during this window in his life that Thomas was transformed from a brutish thug from Putney to a cultured, multi-lingual, man-about-town.

In addition, when Cromwell first took up residence in Austin Friars, he was still plying his father’s trade as a cloth and wool merchant, alongside his profession as a man-of-the-law. Austin Friars was one of the City’s centres for such activity. I have already noted the high population of Italian (and German) merchants. Cromwell must have felt right at home; the vibe, culture and opportunities afforded for doing business in the area perfectly suited his personal tastes and professional requirements.

Thomas Cromwell Moves into Austin Friars

The first evidence of Cromwell at Austin Friars comes in 1525. Thomas was then 40-years-old. He writes to his ‘well-beloved wife, Elizabeth’…’agenst the Freyers Augustines in London be this given.’ He is clearly away from home in Kent but sends her a doe to use at her pleasure. However, Nick Holder notes that ‘he [Cromwell] attended the wardmote meeting for Broad Street ward in December 1522, as though he were already living in the area’. Thus, it is likely that we can date Thomas Cromwell’s arrival at Austin Friars to the early 1520s. At this point, Thomas was in his mid-late 30s and, as noted already, well-established in London’s mercantile and legal communities.

Cromwell’s house at Austin Friars is fascinating. The development of the property is well documented. It reflects, in a very physical way, Thomas’ steady aggrandisement at court, rising from being a mere clerk in Thomas Wolsey’s household to becoming the King’s First Minister and a peer of the realm to boot. He must have held his property in Austin Friars in high esteem for rather than move out and buy a ready-made, larger property elsewhere (as befitting his elevated status), the story of the Austin Friars house during Cromwell’s tenure is one of continual expansion and embellishment.

There are two distinct phases of development to explore. Cromwell’s original rented tenement is the first. The second is the house as it was at its zenith, at the time of Cromwell’s downfall in 1540. Let’s look at each in turn…

Thomas Cromwell’s First House at Austin Friars

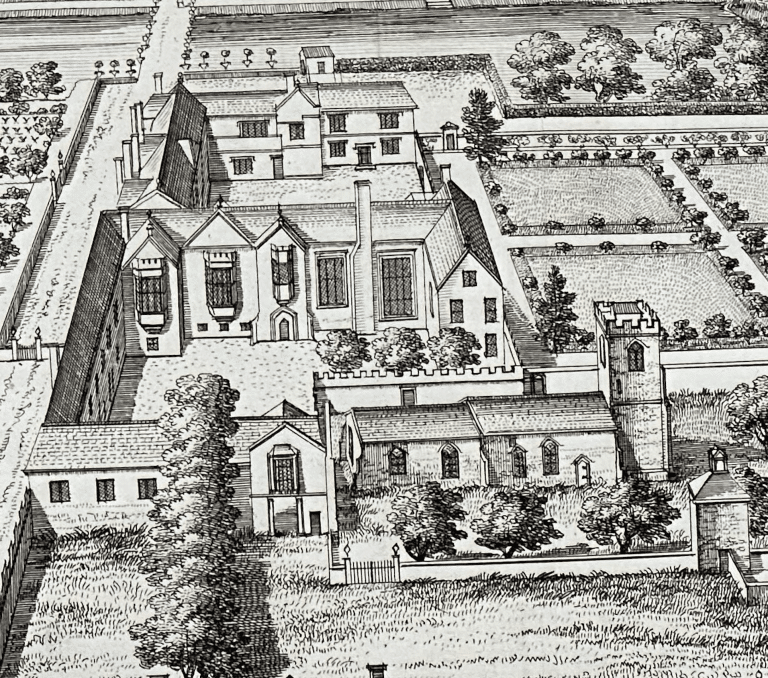

The sources through which we can recreate Cromwell’s house at Austin Friars are several-fold. Thankfully, the house (purchased from the Crown by the Drapers’ Company after Cromwell’s execution) survived long enough to be illustrated on a survey drawn for the Company in the 1640’s or 1650’s. Two inventories survive, one from 1527 (when Cromwell was yet to rise to the dizzy heights he would reach in the mid-1530s) and the second from 1543, three years after his execution. Together, they are illuminating. Thanks to the work of Nick Holder, we can bring all of them together to walk once more through the ghostly corridors of Cromwell’s lost mansion.

The arrangement of the buildings associated with Cromwell’s first house is shown in the figure below. Various contemporary letters indicate that the property was close to the main gateway to the Friary. One letter records the address in 1531 as the ‘dwelling at the Freare Awstens gatehouse’. In its earliest iteration, the house was set back from the main street (Throgmorton Street). It was directly north of a property owned by the aforementioned Italian merchant, John Calvacanti, and a large inn known as ‘The Swanne’. All this would change, as we shall hear shortly!

This first house had three wings or ranges, almost forming the shape of a lop-sided ‘U, enclosing a courtyard (see layout below). The great hall occupied the bottom of the ‘U’. The kitchen and associated offices were off its low end to the west and the family’s privy rooms off the high end to the east of the hall. These latter chambers abutted the edge of the Friary churchyard.

Overall, there were ‘fourteen rooms arranged over three storeys with, in addition, at least one cellar and some garret rooms in the roof’. All the main privy chambers were sited at the first-floor level; bedrooms were located on the second, and the servant’s quarters were in the garret rooms on the roof. The house was entered via a porch which led into a carpeted hall containing ‘several tables and chairs and a mirror’. At the high end, this led into a grand parlour, which Holder notes as particularly ‘impressive’ being ‘carpeted and fitted with a long table and a screen’.

Both the hall and parlour were decorated with a series of religious images; decorative tapestries are noted, including a ‘pycture of occupation and Idylnes’ set alongside paintings, one of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. Holder describes how ‘Cromwell demonstrated his loyalty with two separate painted panels of Cardinal Wolsey’s arms (a canvas one in the hall and a wooden one in the parlour)’. Two altars are also recorded, alongside a generous inventory of silver and gilt plate. On a more personal note, 28 rings are listed, three of which Cromwell was apparently wearing when the inventory was taken. What a wonderful snapshot of a house captured during one fleeting moment in time!

The original house also had a small garden (‘one-twentieth of an acre’). This was sited across the courtyard and to the north of the house. A seventeenth-century survey shows a garden laid out in two, square knots surrounded by gravel paths; perhaps this was the garden that Cromwell knew.

Cromwell’s Second House

By 1532, the future was looking bright indeed for Thomas Cromwell; his patron, Thomas Wolsey, had been dead for two years. Thomas had emerged from the Cardinal’s shadow unscathed by his master’s downfall. His formidable talents in helping his new master, Henry VIII, free himself from the grip of Rome and thereby paving the way for the resolution to ‘The King’s Great Matter’ did not go unrewarded by a grateful king. Cromwell was now all but the King’s First Minister in deed, if not in name.

To keep pace with his elevated status, Thomas set in motion plans to enlarge his Austin Friars home. This was a man on a mission! In June 1532, his ‘grand design’ got underway with the first of several purchases of several surrounding properties, including that previously occupied by John Cavalcanti, as well as the Swanne and Bell Inns, fronting onto Throgmorton Street. This buying frenzy left Cromwell with ‘one of the largest pre-Dissolution private properties in London, owning 2? acres of land, including a 1¼-acre ‘greater garden’ and a quarter-acre ‘lesser gardeyn’.

Having acquired the land, the building project that followed began in July 1535. This was the month that Sir Thomas More lost his head on Tower Hill and Henry VIII headed out on the historic 1535 progress with Anne Boleyn at his side. Thomas was with the royal couple for a significant portion of that progress. Letters signed by Cromwell trace his steps on progress from Winchcombe in July to Winchester at the end of September. During that time, he began to diligently oversee the first ‘visitations’ of the ‘lesser’ religious houses in England. This would eventually snowball into the full-scale Dissolution of the Monasteries.

At the same time, on the domestic front, we might imagine Cromwell bidding farewell to his household in the courtyard of his first, modest home (his wife had died in 1529), leaving instructions for the master architect, or supervisor, a certain ‘Sir John’, to begin the building campaign that would end four years later in July 1539. (It is worthy of noting that apparently everything ground to a halt for a year in 1538, while ‘Sir John’ was away dealing with another of Cromwell’s projects to dismantle the priory at Lewes).

Nick Holder calculates that at least £1,000 was spent (and probably much more, as some of the accounts have been lost) on enlarging the house. In the month following the commencement of the project, 98 workers, primarily carpenters, were working on site. One can only imagine the banging, sawing and hammering that the neighbours had to put up with during this period!

As noted, the house Cromwell was to create was palatial. Much of it was constructed in brick. This was certainly true of the range, which contained the most glamorous chambers and fronted onto Throgmorton Street. However, variable thicknesses of the walls make it likely that at least, in part, some sections of the building were timber-framed and filed in with wattle and daub. The house was, for the most part, two storeys high, except again the front range, which was extended by another floor and contained garrets in the roof for servants’ lodgings.

The front range deserves special attention. A copperplate engraving of the 1550s clearly shows this facade was embellished by three highly decorative oriel windows spanning both the first and second floors, with a large, arched central gateway situated beneath them. This was the main entrance to Cromwell’s triple courtyard house.

By late 1539, just as the Anne of Cleves’ marriage was being finalised, Cromwell’s second house was complete. It contained 50 rooms arranged around the aforementioned three courtyards. A main central courtyard and a second one, accessed separately, lay to the west of the Great Courtyard, which contained a hall and chapel. Finally, a third courtyard was located on the east side of the complex, around which the main kitchen and service offices, such as the buttery, pantry, wine cellar, and pastry kitchen, were arranged.

According to Nick Holder’s ground floor plan, all three courtyards were accessed independently. Clearly, high-status visitors would be welcomed via the great courtyard and then led up a grand staircase (3) to the privy chambers on the first floor, which included two halls (33 and 42), a ladies’ parlour (35) and the principal parlour (36). The hall fronting onto the street not only had the three large bay windows facing onto the street below (which are evident on the copperplate engraving) but one additional one that looked down onto the inner courtyard. The second hall, as you can see from the plan, was even larger. Holder postulates that it may well also have had oriel windows. Both were undoubtedly hung with decorative tapestries, including a set that would be later confiscated by Henry VIII following Cromwell’s execution.

Two galleries connected the ranges (43 and 44) with Cromwell’s private chambers, most likely sited in the north-west corner of the house (45, 46, 50, 51) with views overlooking his, by now, extensive gardens. These gardens are noted to have contained a bowling alley and a maze. Thanks to John Stow and his Survey of London, we are even treated to a snippet of controversy, which clearly raged around the building of those gardens. John Stow’s father was unfortunate enough to own property adjacent to the burgeoning Cromwell family home. Stow leaves us a record of what happened next:

‘This house being finished, and having some reasonable plot of ground left for a garden, he [Cromwel] caused the pales of the gardens adjoining to the north part thereof on a sudden to be taken down; twenty-two feet to be measured forth right into the north of every man’s ground; a line there to be drawn, a trench to be cast, a foundation laid, and a high brick wall to be built. My father had a garden there, and a house standing close to his south pale; this house they loosed from the ground, and bare upon rollers into my father’s garden twenty-two feet, ere my father heard thereof; no warning was given him, nor other answer, when he spake to the surveyors of that work, but that their master Sir Thomas commanded them so to do; no man durst go to argue the matter.’ His next words are poignant, given Cromwell’s precipitous fall. ‘Thus much of mine own knowledge have I thought good to note, that the sudden rising of some men causeth them to forget themselves’.

The House After Cromwell’s Downfall

When Cromwell was executed on Tower Hill on 28 July 1540, he was less than a mile from his cherished Austin Friar’s home. With all his goods forfeit to the Crown, as was customary, his home and contents were seized. Even before his death, after he was arrested on 10 June, there are records of goods being removed the very same day and given to Anne of Cleves as part of her annulment settlement. The property then lay empty for three years until purchased by the Draper’s Company, who still own the land.

Cromwell’s house is long gone, but it witnessed one man’s rise to greatness and dramatic fall. Within its walls, conversations took place, changing the course of English history; the English Reformation was ignited, and the plot to bring down Anne Boleyn may have been hatched there. Many notable names in Tudor history passed through its halls and corridors, including Henry VIII himself and the reformer Miles Coverdale. For around 20 years, Austin Friars was Cromwell’s powerhouse in the city that now, tragically, must live on only in our imaginations.

If you want to hear more about Cromwell’s life, why not tune into my podcast, ‘The Life and Times of Thomas Cromwell: Brutish Thug or Sophisticated Courtier?’ with the author, Carol McGrath.

Sources

First, I must acknowledge a huge debt of thanks to Nick Holder for his outstanding work in pulling together all the relevant documents that allow us to enjoy such a vivid representation of Cromwell’s house at Austin Friars. You can buy his book on The Lost Friaries of Medieval London here or download his excellent PhD thesis, which contains this information, here.

Other sources I found helpful in writing this blog are:

Roger Bigelow Merriman. “Life and Letters of Thomas Cromwell, Vol. 1 of 2 / Life, Letters to 1535”.

The Survey Of London by John Stow

Very interesting what stands on the grounds of Austen Friars now

What a marvellous article on poor Thomas. I only realised this was where his house was because of a small plaque on a wall nearby. I had to walk through this area to go to my physio nearby.

Glad you enjoyed it!