Waltham Abbey, Essex

Distance from London: 20 miles

‘[The King] rode to Waltham; and from thens the High Way to Cambridge…’ Cotton Manuscript Julius B XII

We know from the records of Henry VII’s Herald that after leaving London, ‘the king first rode to Waltham’. Unfortunately, no further detail is provided of when Henry arrived in the town, where he was lodged, or indeed how long he stayed. In Cavell’s thesis entitled, A Memoir of the Court of Henry VII, the author says that the purpose of the visit was ‘devotional’ and to understand this, we need to consider the history of the town and its great abbey and reflect on the context associated with Henry’s visit.

If religious devotion was indeed the purpose of the visit, it may also steer us toward understanding the most likely location of the King’s overnight stay.

A Short History of Waltham Abbey

The village of Waltham was established by King Canute’s standard bearer, Tovi the Proud, in the early eleventh century, before the Norman Conquest. A wealthy and powerful Anglo-Danish Thegn, Tovi settled a village of sixty-six households, amounting to somewhere in the region of 300 people, on the site of what was to become the heart of Waltham Abbey. He also built a convent in which to house a Holy Cross, said to have been brought to Waltham by a miracle.

From the time of Edward the Confessor, Waltham became inextricably linked with the Crown. Edward conferred a considerable land grant upon his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, who enlarged the original church and established the first religious house there. This eventually became an abbey in the year 1184, when Henry II appointed William de Gant as the first abbot. According to The History of the County of Essex, ‘on account of its size, royal patronage and proximity to London, [Waltham] was one of the most important houses in England; certainly, the most important of those of the Augustinian order.’

The miraculous power ascribed to the Holy Cross at Waltham became legendary. Consequently, the power of Waltham to attract pilgrims grew, along with the influence of its church. This church was peculiar because it was always a royal free chapel exempted from episcopal control.

Thus, from its humble beginnings, Waltham was patronised by royalty. This was not only on account of the divine powers of the Cross, whose blessing the Kings of England no doubt craved but also on account of the geography of Waltham’s environs.

Waltham was only approximately twenty miles from London; it was not only possible to reach it overland but also by boat via the River Lea which, according to Leland’s Itinerary, originated three miles upstream from the town (although in truth, the River Lea originates many miles before that!) and discharged itself directly south into the Thames at Woolwich. This was almost adjacent to Greenwich Palace, a place greatly favoured during the early Tudor period. Furthermore, the only navigable part of the river at Waltham was called ‘King’s Stream’, indicative that the river was used regularly by the monarch to access Waltham from central London.

However, most importantly, Waltham sat adjacent to Waltham Forest (today the tiny remnant of this forest is known called ‘Epping Forest’), which rose gradually from the rich alluvial marshes and meadows near the river to a plateau of London clay in the east. The forest stood on this plateau, providing a playground for the Kings and Queens of England.

Apart from its situation and the possibility of good hunting, the Holy Cross at Waltham was also associated with a divine power to heal the afflicted. Certainly, we know that in the reign of Henry VIII, it was to Waltham that the king fled when the Sweating Sickness broke out in London. A few years later, it was where Thomas Cranmer would take refuge when the plague was rife in the city. Indeed, it was during that stay, at the house of a ‘Mr Cressy’ (whose sons Cranmer tutored) in Romeland, close to the abbey church, that the historic conversation occurred in which Cromwell quizzed Cranmer about his novel ideas on how the King might find a way to divorce Katherine of Aragon.

The Royal Lodgings at Waltham Abbey

We have no definitive account of where Henry VII lodged during his stay in Waltham, although there is more than one possible contender. Henry VIII had a residence in Romeland – a close of houses near the abbey’s gatehouse. Did he inherit that from his father? We do not know, but it is possible. Another possibility is the great Copped Hall, situated around 3 miles from the centre of Waltham. There had been a manor house on the site since the early medieval period, and at the time of Henry VII’s visit, was owned by the Abbots of Waltham, who used it as a mansion of pleasure and privacy.

However, bearing in mind the ‘devotional’ purpose of Henry VII’s visit, I believe that the most likely contender would have been the abbot’s lodging close to the abbey church. All great abbeys followed a similar layout –firstly the dominant abbey church, usually with a cloister lying to the south (to catch the sun). Surrounding the cloisters were conventual buildings, such as the refectory and chapter house. Sometimes, the abbot’s lodging was attached to the cloister; at other times nearby and set separately from it. It was the most palatial building of the abbey complex after the church.

These lodgings were frequently used by royalty during their progresses. Oftentimes, the abbot would cede his quarters to the King. However, at Waltham, we find the more unusual arrangement of specific chambers being set aside for the King and Queen permanently. It is clear from an account of the reign of King Edward I that these chambers existed from the early medieval period.

There is a story about Edward and his beloved queen, Eleanor, staying at Waltham over Easter. After a hard day’s hunting, the King retired to his chamber; soon after, he was playfully set upon by the Queen and her ladies in a traditional game called ‘heaving’. The king was bound to a chair and only released when he agreed to their ransom. Whilst this is an interesting story, from our point of view, the more important point is that the account mentions ‘the royal chambers of the king, close to the abbey church’.

The inventory of the abbey taken at its dissolution in 1540 is an invaluable resource in our quest to uncover the lost royal lodgings at Waltham. Fortunately, the inventory of the seized goods is listed by room, so we learn of several sacred and domestic buildings and their furniture, all connected to the abbey and these royal lodgings.

It seems that the abbot’s lodgings at Waltham were considerable; a great hall comes first, followed by the abbot’s ‘utter’ [outer] parlour; then a ‘thinner’ [inner] parlour containing such furnishings as, tables, cupboards and carpets used as hangings; there is a ‘Grete Somer Chambor’ [chamber] and corresponding ‘Wintor chambor’; ‘the Abbotts Chambor’, which contained a featherbed, bolster and pillow, a ‘plaine new coffer’ and folding bedstead used in travelling, along with six cushions. Also listed are the ‘abbot’s inner chamber’, wardrobe and private chapel.

Then, we specifically hear of ‘The Kings Chambor’. This contained a folding bedstead, two featherbeds, two pillows and two bolsters; hangings of green silk with ‘borders of painted cloth’; a little square table, two cupboards, two old turkey carpets, two Kentish carpets, a Flanders chair and three old white cushions. As we might expect, there was also a ‘Quenes Chambor’ which was similarly furnished, including a set of old ‘Aris’ [Arras – tapestries] and a ‘trundell bedstede’ which was a smaller truckle bed, stored rolled under a standing bed.

Although now entirely lost, the abbot’s lodgings seem to have been located off the north-west side of the cloisters (the cloisters at Waltham were unusual in that they lay to the north of the abbey church). This made them readily accessible from the main abbey gatehouse. However, the exact arrangement of how the rooms related to one another is unknown.

The scale and importance of these lodgings to the Crown might also be underlined by the fact that several historic records mention ‘the king’s stables’ at Waltham Abbey. A review of all these sources by Peter Huggins of The Waltham Abbey Historical Society called, The “King’s Stables” at Waltham Abbey, and other local Tudor Interests concludes that the stables lay about half a mile to the south of the abbey, in a similar arrangement to the that seen at Hampton Court. Clearly, this location was in use frequently enough to house ‘les charet horses of the king’.

The Royal Lodgings at Waltham After the Dissolution

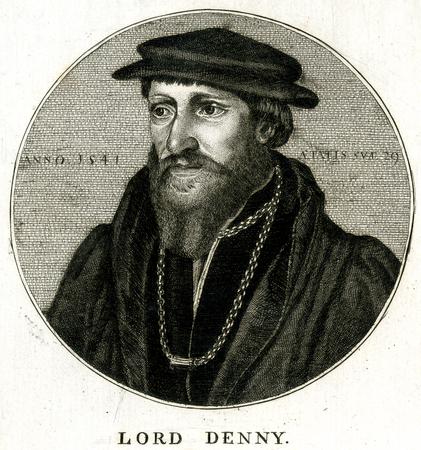

After the Dissolution, the abbot’s lodgings at Waltham met a fate similar to many others around the country. The Court of Augmentations gave the abbey to Sir Antony Denny, a Gentleman of the King’s Privy Chamber, who was made:

‘keeper of the site and chief messuage of Waltham monastery, Essex, and of the waters in Waltham Holy Cross, Essex’.

The Court of Augmentations for the same year also lists Sir Antony as Keeper of the Abbey Site and the King’s Mansion House at Waltham. In other parts of the country, such as York, Dartford, Rochester and Canterbury, we know that after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, previous monastic buildings that had hitherto been used regularly by the royal court as staging posts along major routes were often converted to royal lodgings and given the name ‘the King’s Manor’, or similar. This allowed for the monarch’s continued use after the monastic church had been dissolved. Although we have no direct proof that the royal lodgings included in the inventory of 1540 were indeed part of the new King’s mansion, it seems the most likely possibility.

The ‘High Way’ at Waltham Abbey

One of the few facts we have about the early part of Henry VII’s progress is that he took the ‘High Way’ from Waltham to Cambridge. This was a major route north from the City of London to York in the sixteenth century and was based on the old Roman Ermine Street. Winding his way north from the Hospital of St John, the cavalcade would eventually have reached a branch off the main road, heading eastward towards Waltham Abbey.

At this junction stood the ornately carved ‘Eleanor Cross’; it was one of the 12 stone crosses that King Edward I had carved in memory of the sites where his wife’s body rested on its way back to London. Eleanor’s body had laid at Waltham. However, the cross seems to have been erected at this major junction of two roads, likely because it was here that it would have been most visible to passers-by.

By the sixteenth century, there was possibly a tiny smattering of buildings that had grown up around the cross, including two coaching inns. Interestingly, engravings of how the cross appeared before the area was heavily built-up show the branch road winding its way toward Waltham and a large edifice, quite probably of the abbey church, in the far distance.

Today, the branch road adjacent to the cross is pedestrianised and part of a busy shopping centre. If it were ever possible to see the abbey from this junction on the major route, it is certainly no longer the case. However, if you choose to go and see the restored Eleanor Cross, as I did, it is quite easy to let the busy hustle and bustle of everyday life melt away and see Henry, upon his horse, part of a magnificent entourage, snaking its way to and from the royal citadel at Waltham Abbey.

Visitor information

Any visit to Waltham Abbey has to begin outside what remains of the abbey church. Today, it is known as The Parish Church of St Lawrence. You might be lucky and find a parking space directly outside – although parking is very limited here. Alternatively, there is parking nearby Cornmill car park (EN9 1RB).

Close to the west end of the church, on Highbridge Street, is the Tourist Information Centre. You may find it helpful to pop in and ask for the ‘Discovery Walk’ of ‘Historical Waltham Abbey’. Another useful booklet, A Walk Around Waltham Abbey details various points of interest around the town, including a map on how to find them.

The route we are about to take you on does not entirely fit with that described in the Discovery Walk brochure. However, there is overlap, and it would give you an excellent overview of the key historical sites, buildings to see, and places to visit in the town, outwith our focus on the early Tudor period, if that is of interest to you.

Once you are standing in front of the church, look up and notice the tower. This was built in 1556 and replaced an early Norman one which collapsed around 1553. It is said to be the only church tower built anew in England during the reign of Mary I, not counting rebuilds. Although the church’s exterior is unremarkable, its interior is magnificent, boasting two colonnades of distinctive Norman pillars and a finely painted ceiling. Do note, though, that this ceiling was part of the restoration undertaken in the nineteenth century and is not original. However, it gives a fine idea of the colour once associated with the medieval abbey.

At one time, the parish church connected via a doorway at its east end with the ‘true’ abbey church, the domain of the abbot and his brethren. You can see the bricked-up doorways more clearly from outside at the east end of the church (where we will head shortly). When you have investigated all the church has to offer, including its famous fifteenth-century Domesday painting, head back outside and follow the path to the right, heading north, until you soon come across what remains of the main abbey gateway.

Once inside the gateway, walk forward for a few metres; you will see an open grassy. area to your right. This area, between the abbey and where you are standing, once contained the abbot’s lodgings and therefore, the royal chambers. Nothing remains today except a pile of brambles and some shrubbery. Continue to explore the park, once enclosed to form the abbey precinct and now opened up to the public as the ‘Abbey Gardens’. Walking further on ahead, and over to your right, through a small doorway, you will find all that remains of the abbey cloisters. Beyond these cloisters, make your way towards the rear of the church – and the supposed burial place of the last Saxon king, Harold II.

The east end of the current church shows scars of where the original abbey building once adjoined it – including the outline of two bricked-up doorways that we mentioned earlier. Try and find the tracing of the semi-circular east end of the Norman church and its transepts laid out in the ground near the east wall. The transepts were also the transepts of Harold’s earlier church, and you can still see some of his church’s herringbone rubble masonry in the east wall of the Lady Chapel. Now walk away from the church with your back to its east end, and keep going until you reach a cluster of small trees on your right, just before the moated area. You are now standing about where the east end of the abbey once stood. Looking back, you will see just how massive the abbey at Waltham once was! It rivalled Westminster in length.

You can cut through from the Abbey Gardens onto Sun Street and head to the Epping Forest District Museum. It is beautifully arranged with some fascinating local artefacts, including some exquisitely carved oak panelling, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Documented evidence shows it was once in Abbey House, a mansion built by Sir Anthony Denny after the Dissolution. However, as it contains symbols relating to the early Tudor period, including a Beaufort portcullis, a Tudor rose and a split pomegranate of Katherine of Aragon, it is just possible it may have originally been fitted in the royal apartments which we have been discussing. It is a tantalising possibility!

There are many places in Waltham for refreshment, but most conveniently there is a very pleasant, small café almost opposite the entrance to the church called The Gatehouse Café. It is a perfect place to rest and digest all you have seen as you imagine Henry VII’s royal cavalcade passing by the window as the King heads into the abbey precinct to take up his lodgings in what was essentially a long-established royal citadel.

Postcode for the Parish Church of St Lawrence: EN9 1DJ

Postcode for Epping Forest District Museum: EN9 1EL

THE NEXT STOP ON THE PROGRESS IS ‘CAMBRIDGE’. Click here to continue on your way.

Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest

Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge: (4.5 miles) This hunting lodge is a delightful survivor in the heart of Epping Forest, Today it is managed by the City of London, and their website encourages us to ‘Explore the Tudor history of Epping Forest at Queen Elizabeth’s Hunting Lodge, built in 1543 for King Henry VIII and renovated by order of Queen Elizabeth I.’

Hertford Castle: (13 Miles) Hertford Castle was originally built on the site of a Norman Castle situated by the River Lea in Hertford, the county town of Hertfordshire. The building dates from the mid-fifteenth century situated in beautiful grounds at the heart of Hertford. The Castle was a Royal Palace for over 300 years. it was undoubtedly visited by Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, Edward VI and Queen Elizabeth I. Only the gatehouse of the castle’s complex of buildings survives. Check out the castle’s website for visitor information. Hertford Castle is also one of the 70 locations in my co-authored book In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn.

Hatfield House: (17 Miles) Hatfield House, more than any other location, may be considered to be the childhood home of Elizabeth I. Although Elizabeth moved around as a child, Hatfield was her favourite residence. It was also the place where she was residing when she discovered that she had become queen at the age of 25. You can read more about the Old Palace at Hatfield via my blog: The Old Palace of Hatfield: The Cradle of the Elizabethan Age. Hatfield House is also one of the 70 locations in my co-authored book In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn.

Ingatestone Hall: (22 Miles) Ingatestone Hall is a sixteenth century manor house in Essex. It is located outside the village of Ingatestone, approximately 25 miles north east of London. The house was built by Sir William Petre, and his descendants live in the house to this day. The Hall has received royal visits from Mary I and Queen Elizabeth I.

Layer Marney Tower: (47 Miles) Layer Marney Tower is what remains of a once magnificent Tudor manor house, composed of buildings, gardens and parkland. It was constructed in the first half of the reign of Henry VIII, circa 1520. The gatehouse tower at Layer Marney is in many ways the apotheosis of the Tudor gatehouse and is the tallest example in Britain. Quite spectacular!

Leez Priory: (35 Miles) Leez Priory was once the country seat of Sir Richard Rich. It was built following the priory’s dissolution, after which it is named. Today only fragments of Rich’s fabulous country home survive, including a fine outer gatehouse range and a splendid inner gatehouse. It has been an exclusive wedding venue for the past 30 years. technically, it is not open to the public. However, if you phone ahead and a wedding is not scheduled, you may be allowed to wander around – and belive me, you will love this hidden gem! If you would like to read more about Sir Richard Rich at Leez Priory then check out my blog: Leez Priory & The Most Notorious Villan in Tudor History

Sources and Further Reading

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

The History of the Ancient Parish of Waltham Abbey, Or Holy Cross, by William Winters. 1888

A History of the County of Essex: Volume 2. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1907.

The Excavation of an 11th-century Viking Hall and 14th-century Rooms at Waltham Abbey, Essex, 1969-71, by P.J. Huggins for The Waltham Abbey Historical Society.

Monastic Grange and Outer Close Excavations, Waltham Abbey, Essex, 1970-1972, by P.J. Huggins.

Edward I, by Robert Seeley.

The “King’s Stables” at Waltham Abbey, and other local Tudor Interests, BY P.J. Huggings for The Waltham Abbey Historical Society.

Many thanks to Clive Simpson, a local historian, for his enthusiastic help in researching the lost royal lodgings at Waltham Abbey.