Cowdray House & the Sinister Curse of Fire and Water

Every now and again, a tragedy befalls a Tudor house that is so catastrophic that the sorry tale makes you want to weep at the mere thought of what has been lost. The focus of this blog tells such a story. On the fatal night of 24 September 1793, a fire broke out in one of the most significant and majestic Tudor houses in England. It spread through the building with an angry fury that was unstoppable. As the sun rose, the house had been devoured, such that all that remained was ‘blackened walls and dismay and ruin’. This is the story of Cowdray House and the curse said to haunt the descendants of one of the most powerful men of the Tudor age.

If you want to listen to me on location recording an episode of my podcast, The Tudor History & Travel Show with our expert guide, Paul Ullson, then you can now do so by tuning in here.

The Rise and Rise of William Fitzwilliam

My attention was first drawn to Cowdray when I was writing my novel, Le Temps Viendra: A Novel of Anne Boleyn. In researching the second volume, I had the misfortune to spend time with a gruff and austere character: Sir William Fitzwilliam, one of the three royal councillors appointed to initially interrogate Anne Boleyn, following her arrest at Greenwich Palace. A contemporary account of William Fitzwilliam’s survives. During his lifetime, he was described as a ‘wise, discreet and sober man’ who ‘hath the language of the French tongue’. His cunning is also without doubt; during the same rout of the Boleyn faction in May 1536, it was Sir Henry Norris who accused Fitzwilliam of falsely procuring a confession of his guilt in relation to accusations laid against him.

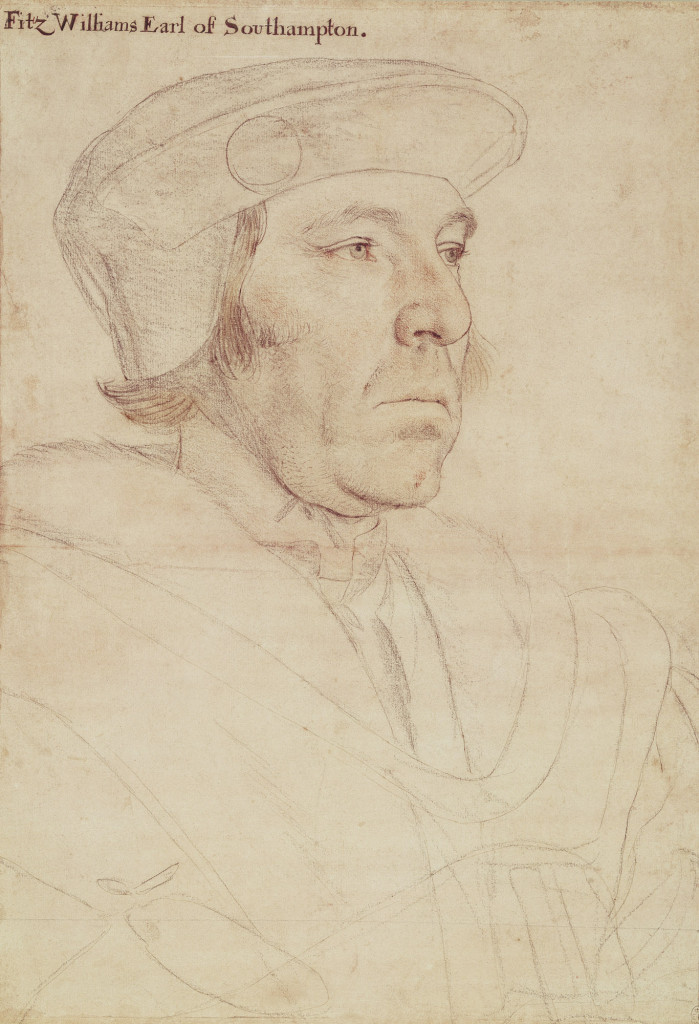

In addition to the descriptive legacy of Fitzwilliam’s character, we also have a surviving Holbein sketch of the man. When I first studied this, his cold, penetrating gaze and course features reminded me of Cromwell’s (similarly captured by Holbein) and in my novel, I described his character as being ‘hewn from the granite of Yorkshire’, which was his paternal country of origin. You decide for yourself; would you like to be on the wrong end of Sir William’s displeasure?

Fitzwilliam was of noble descent. His mother, Lucy Neville, was the niece of Warwick the Kingmaker. Perhaps it was because of these blue-blooded connections, and his close proximity in age to the young Prince Henry, that William was placed in little Henry Tudor’s household and was brought up from boyhood alongside the future king. Like another of his contemporaries raised in the schoolroom with Henry, Charles Brandon, Fitzwilliam would forever remain in high favour at the Tudor court and, as the years marched on, William was granted ever more significant royal offices and titles.

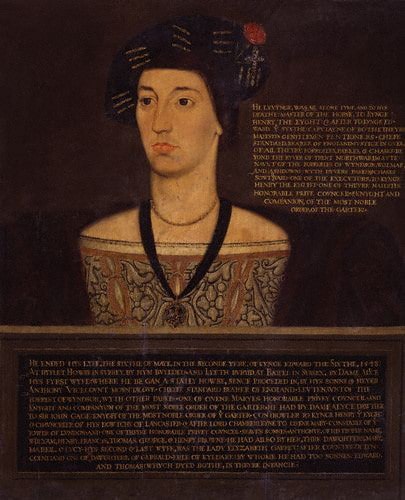

So, shortly after Henry VIII’s coronation, FitzWilliam was appointed as the King’s Cup Bearer and Gentleman Usher; he forged a successful diplomatic (probably due to his fluency in French) and naval career. The latter ultimately earned him the position of Lord High Admiral of the English fleet (granted in 1540). By Oct 1525, Fitzwilliam had become Treasurer of the Royal Household and by 1526 a member of the inner ring of king’s royal councillors. However, I suspect that it was his eagerness to cooperate with the king and Cromwell to bring about the downfall of Anne Boleyn in 1536 that raised his cache at court. As a result of his diligence and success in serving the Crown, Sir William was ennobled as the 1st Earl of Southampton in 1537.

Cowdray House and the New Earl of Southampton

As Sir William’s fortunes and favour were on the rise, he naturally required a suitable country seat commensurate with his newfound status. He had acquired Cowdray House, in Midhurst, Sussex, in 1529, from Henry Owen, son of the long term Lord of Cowdray, Sir Davy Owen (who BTW, was uncle to Henry VII). Around the year 1520, Sir Davy pulled down the old, medieval, moated manor house and began to construct a new, single courtyard, renaissance-style home in its place. We should remember that great palaces such as Hampton Court and Otford were being built at exactly the same time. So, perhaps it is not surprising that comparisons are drawn between the former and the grand, Tudor house being constructed at Cowdray.

Although the property now belonged to Sir William, Sir Davy retained a lifetime interest. This meant that Fitzwilliam only moved into the burgeoning Cowrday House in 1533, after the latter’s death. At this stage, only part of the east range, containing the privy apartments, had been completed. Sir William soon set about enthusiastically aggrandising his new, Sussex home, thereby completing Sir Davy’s original plan of four ranges centred on a large, central courtyard. Unfortunately for Sir William, he died in 1542, leaving the house unfinished. It was his half-brother, Sir Anthony Brown, who inherited Cowdray House thereafter and who completed its construction.

In all, Cowdray took around 22 years to build, but the legacy was a magnificent Tudor house, crammed with glorious, renaissance, architectural details and stuffed full of precious Tudor artefacts, including it is said, several Holbein portraits alongside other, historically irreplaceable, pieces of art that depicted momentous events of the Henrician age. As we will see, around 200 years later, it would all go up in smoke in an unforgivable act of gross carelessness – or perhaps we might blame the Curse of Cowdray?

Sir Anthony Browne and the Curse of Cowdray

If you relish stories of the supernatural, then there is none more chilling than that of the Cowdray Curse. Did the end of Cowdray House come about through a sheer act of carelessness, or were more malevolent and sinister forces at work behind the scenes? Was the doomed fate of the house foretold?

Following the death of Lord Southampton, Sir Anthony Browne, the king’s Master of the Horse and trusted royal councillor, took up his role as the lord of Cowdray House. However, Cowdray was not the only estate in Sir Antony’s property portfolio. Like so many men on the rise at the end of the 1530s, he profited enormously from the Dissolution of the Monasteries and was granted Battle Abbey and nearby Easebourne Priory upon their disbandment.

The story goes that when Sir Anthony was holding his first feast at Battle Abbey, an enraged monk strode through the crowd, mounting the dais and cursing him to his face. The monk ‘prophesied that the curse would cleave to his family until it ceased to exist. He concluded with the words, “By fire and water thy line shall come to an end, and it shall perish out of the land”.’ However, nothing happened to Sir Anthony, his immediate descendants or his home. He continued to live a life of privilege and prosperity. If there was indeed power in this curse, then it would not rear its deadly spectre until 200 years later…

The Layout and Appearance of Cowdray House

Before we come back to talk about the chilling end of Cowdray House, let’s take some time to enjoy it in all its Tudor splendour!

Thankfully, alongside the ruins (which are grade I listed today), we have a copious amount of material that has survived, allowing us to reimagine this sumptuous, Tudor house in all its glory. Prior to its ruin, sketchings were made of the external ranges of the house, its courtyard, some of its principal chambers and most notable paintings. Inventories and ‘remembrances’ of the interior of the building add to the richness of our understanding of how Cowdray House appeared before its destruction in the eighteenth century.

If you want to read about the house and contents in much more detail, I have included a couple of excellent sources in the section at the end of this blog. There is simply too much to cover here in its entirety. Instead, I will start by giving an overview of the layout of the house before focusing on the most painful of its known lost treasures: the Cowdray Murals.

Cowdray House was typical of an early Tudor great house, built by influential men of the court. It was constructed at a similar time as Thornbury Castle in Gloucestershire and The Vyne in Hampshire. It was fashionably symmetrical, which according to The Castles Study Group had ‘gatehouse blocks with octagonal turrets, with quoins in contrasting alternating bands of ashlar; quadrangular ranges with tall deep bay windows looking outward, but still maintaining the castellated features that announced to the world that they [the owners] had the king’s favour and patronage. Yet they needed to be careful to dissociate themselves from blatant self-aggrandizement, or they would suffer the fate of the Duke Buckingham and the Earl of Surrey.’

The floor plan in the figure below illustrates the layout of the ground floor: an impressive three-storey gatehouse gave entrance to a large inner courtyard. At its centre, was a fountain made of marble, bronze, brass, copper and lead. It survived the house’s ruin and can be seen today in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Opposite this west range was the east range, which contained the splendid great hall, known as the Bucks Hall. The hall was topped by an octagonal, two-storey louvre, inlaid with decorative windows and surmounted by golden weathervanes. It would have been an impressive sight, a ‘beautiful combination of tracery and pinnacles’, probably the work of Sir Anthony Browne.

The hall itself was entered at the low end via an ornate porch, decorated with a vaulted, carved ceiling that has survived in a glorious state of preservation. Above the entrance to the porch was Henry VIII’s coast of arms. Inside, the ceiling is embellished with a plethora of emblems of the house of Tudor, the initial ‘WS’ (William, Lord Southampton) and repeating anchors, thought to refer to Fitzwilliam’s position as Lord High Admiral of Henry VIII’s ‘army at sea’.

The porch gives entrance into what once the screen’s passage of the great hall; the door straight ahead leading on to the eastern gardens. Three passageways on the right led to the pantry, buttery and kitchens, as would be traditional of any great house of the day. To the left and through the screens was the Buck Hall, so-called because the walls were adorned with eleven life-sized, wooden bucks. One of these had about its neck a bow used by Queen Elizabeth I during her visit to Cowdray House in 1591.

The hall was handsomely lit by three elevated windows on its west side and one enormous and exceptionally fine, square, oriel window sited at the high end of the hall; this extended from floor to ceiling. All were set with stained glass that bore the coat of arms of the family, of England and France, and of Henry VIII. Beneath your feet, the floor was once laid with white, marble slabs. Around you, the walls were once been panelled with cedar, while the screen at the low end of the hall was carved with the cognizance and initials of Lord Southampton.

To quote from The Castles Studies Group, ‘The hall was one of the finest buildings in England of its date and type, built in the style of the halls at Wolsey’s Hampton Court (97 x 40 ft) and Christ Church, Oxford (114 x 40 ft), possibly by the same designer, John Nedeham. Cowdray is 60 x 28 ft and 60 ft from the originally paved marble floor to the apex of the great steep-pitched hammer-beam roof.’

Behind the hall, on its eastern side, was a lobby area; directly off to the right was the east-facing chapel with a three-sided apse, similar in design to the surviving chapel at The Vyne, in Hampshire. It is thought that they were possibly created around the same time and certainly contemporary to the building of the hall. The tiles on the floor were from the time of Henry VIII (1520s-1530s).

Directly ahead was the grand processional stair, which lead off the hall’s high end up to the first floor, privy apartments, while to the left was the Great Parlour. This room measured about 40ft by 21ft, its walls wainscotted and plastered to display the great Cowdray murals, to which we shall return shortly. A ‘handsome archway’ led from the parlour directly to the dais, at the high end of the Buck Hall.

On the first floor, at the head of the stair, was a doorway leading to a private closet looking down onto the body of the church; off to the right was the entrance to the Great Chamber, sited directly about the Great Parlour on the floor below. Beyond this, were the most privy apartments of Cowdray House, including the Velvet Bedroom in the adjoining, hexagonal, north-east tower. This was the principal bedchamber used by the Earl. Naturally, it was ceded to any visiting monarch and there are records of Elizabeth I being accommodated there during her stay at Cowdray. The chamber was adorned with a large window that give spectacular views over Cowdray Park.

It is also worth mentioning that the north and south ranges both had long galleries at the time the house was constructed. Both endured for 250 years thereafter, until the latter was subdivided into bedrooms in 1784. The north gallery remained intact. It connected the northeast with the northwest tower, and so could be accessed directly from the privy apartments. Its walls were clad with Norway oak and, like most long galleries, it seems to have been used to display pictures.

Here begins our sorry tale; the treasures of Cowdray House were being stored in the North Gallery during renovations to the house on the night that the fire took hold. As we will hear shortly, the fire originated in a carpenter’s workshop sited on the second floor of the nearby north-west tower. Thus, through tragic happenstance, so many precious objects were lost,

The Cowdray Murals

Before I talk about the Cowdray Murals, which were lost in the devastating fire of 1793, I need to acknowledge what else is thought to have been destroyed that night. Make sure you have tissues at the ready, as this is going to hurt. Firstly, let’s start with the paintings.

Cowdray House was known to have a sumptuous and valuable collection of paintings by some of the most celebrated artists of their day, including some by Holbein. Visitors to the house, prior to the fire, recorded several notable objets d’art. These included a depiction of knights running at the tilt during the Field of Cloth of Gold entitled, The Meeting of the Kings between Guines and Arden in the Vale of Gold. Another is of the Duke of Suffolk, alongside Fitzwilliam, in the presence of King Francis I. It seems to depict the pair on an embassy to France.

While neither of these was thought to be by Holbein, Horace Walpole, who was writing about painters in the reign of Henry VIII suggests that ‘In the great drawing-room [parlour] at Cowdray is a chimney-piece painted with grotesque figures in the good taste of Holbein, and probably all he executed at the curious old seat; the tradition in the family being that he stayed there but a month’. Personally, I’d say that is plenty of time to make some preparatory sketches that might be finished later in the artist’s studio. I mean, if you have one of the world’s most celebrated painters as your house guest for a month, are you not going to ask him to capture your likeness? Unlikely!

However, a catalogue of all the paintings at Cowdray was made around 15 years before the fire, in 1777. One of these is a painting of Erasmus and is thought to have been painted by Holbein, while another was a full-length portrait of Charles V, the future Holy Roman Emperor as a boy, this time executed by another doyen of the art word, Titan.

In addition ‘more valuable than the rest’ was a collection of artefacts from the Norman Invasion. These had made their way to Cowdray House from Battle Abbey (founded on the orders of William the Conqueror to commemorate the place where the Saxon King Harold was slain). These relics were said to include William’s sword, his bejewelled coronation robe and the Roll of Battle Abbey (a list of the companions of Duke William, who came over with him to England). Mon Dieu!

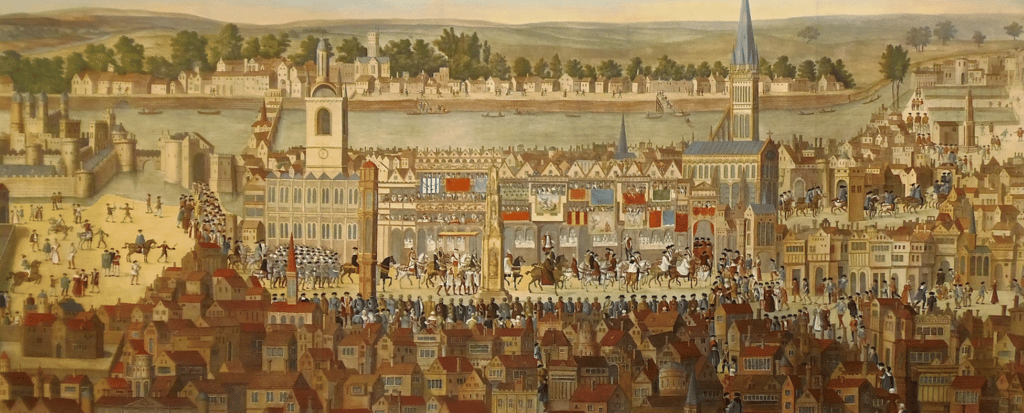

However, Cowdray House is also famous for its lost murals. There were six, large paintings in all. Three were on the south side of the parlour, each depicting scenes from Henry VIII’s successful seige of Bolougne (1544). Three others adorned the north wall, with the middle of the three positioned above the fireplace. One of these showed ‘The Attempt made by the French to invade this Kingdome in the year 1545‘; one showing the battle of the Solent in which the Mary Rose sank (19 July 1545) and finally, the third depicting the coronation procession of King Edward VI from the Tower of London (1547). It is believed that they were all commissioned during Sir Anthony Browne’s tenure of the house, between 1545 and 1548, as they illustrate historic events in which Sir Anthony paid a key role.

The murals decorated the walls of the Great Parlour, which functioned as a splendid dining room. Dominic Fontana, from the University of Portsmouth, has researched the murals extensively (see ‘Sources’ below). He paints an evocative picture of how ‘their location in the dining room might suggest that Sir Anthony intended these images as “visual aids” to support his storytelling at dinner’. They certainly would have entertained his guests and underlined Sir Anthony’s status at the heart of English affairs. He was, after all, the man who had the unenviable task of telling Henry VIII that he was shortly to die when the king was gravely ill in January 1547.

While the original murals went up in smoke with the fire, thankfully engravings had been taken prior to their destruction. While both the sinking of the Mary Rose and the coronation procession of Edward VI have been repainted, the others remain as simply line sketches, which nevertheless show incredible detail, which you can happily lose yourself for hours!

The End of Cowdray House

At about 11 o’clock at night on 24 September 1784, flames were seen coming from the windows of the carpenter’s workshop in the north-west tower. Smouldering embers from a fire had ignited sawdust strewn across the workshop floor. Soon the tower was ablaze. The ferocity of the fire quickly tore through the enclosed space of the adjacent north gallery, where every single painting that could be moved had been stored during the ongoing renovations to the house. The first devoured almost the entire contents of the gallery. Only three, relatively insignificant, paintings were saved from the blaze.

Confusion and mismanagement did not help matters the firehouse and water buckets had been misplaced, locked away in a separate building – and no one could locate the key. People from the nearby village of Midhurst flocked to the house to see if they might help, but there was little that could be done. Attempts were even made to tear down a portion of the building, to sacrifice it to save the rest, but the strength of the masonry rendered this futile.

By 7 o’clock the next morning ‘that ancient and noble structure, with all its capital paintings, furniture etc, a collection which no traveller of taste ever neglected to view or returned ungratified was gutted and a smouldering ruin’. Worse was to come. Just a few days later the 8th Lord Montague, who was away in mainland Europe drowned while trying to shoot the rapids at the falls of the Schauffhausen on the Rhine. He was unaware the Cowdray House had burnt down. One has to feel enormous compassion for Lady Montague, who was bereft; she lost her husband and home in a matter of days, if not hours.

Today, the house stands in charred ruins. It is a stalwart reminder of an illustrious, Tudor past. Its blackened, hollowed-out remains are a haunting echo of a singularly careless act that destroyed it and some of the most treasured historical artefacts of the Tudor age – or is it that its ghostly walls whisper to you of a sinister curse cast upon a noble house, a curse that by fire and water had brought Cowdray and those who lived there to their knees…

Sources

Cowdray House, by The Castles Study Group

Cowdray: The History of a Great House, by Mrs Charles Roundell. Bickers & Son: London. 1884.

Biography of Sir William Fitzwilliam by Tudorplace.com

The Cowdray Engravings and the Loss of the Mary Rose, by Dominic Fontana

Sarah, thank you so much for such a delightful, if sinister, diversion. I broke my leg last week so you provided some very much needed distraction. xxx

You are most welcome, Cheryl! I hope that leg gets better soon. x

Absolutely love your blogs Sarah. Fascinating read.

Thank you so much!

Thank you Sarah! This was an absolutely fascinating blog, as always. I love the ‘rogue-ishness’ of Holbein’s sketch of Fitzwilliam and would definitely hate to cross him 🙂

Finally catching up on all things Tudor. I love your writing style. So evocative and I especially enjoy the humorous asides. Thank you for always bringing Tudor history to life for us!