Otford Palace: Rivalry, Glory and Ruin in the Tudor Age

Otford Palace, in Kent, was once acknowledged as being the most magnificent house in England. The man who was singularly responsible for its aggrandisement, William Warham, then Archbishop of Canterbury, was locked in rivalry with the Thomas Wolsey. At the time, Wolsey was in the ascendant, fast becoming the second most powerful man in the realm.

The two men of the church were famously not friends and one suspects that it was jealously that drove a wedge between them and, perhaps, sparked the ambition to outdo each other through the palaces they built. As a result Warham’s palace at Otford certainly rivalled, if not surpassed Hampton Court in scale, being the first of the two houses to be completed, by 1515.

Although only a fragment of the original building survives, Otford Palace is dripping with Tudor history. Many of the most recognisable names of the period have walked its corridors and strolled among its pleasant gardens. This blog is intended as a supplement to this month’s Tudor History & Travel Show, in which I visit the remains of Otford Palace and hear about how rivalry and glory first shaped the palace’s history, before it fell swiftly into decay when it was effectively abandoned by the Crown in the mid-late sixteenth century.

You can listen to the episode here, alongside the text and images below to get the most from your audio experience.

The Origin of Otford Palace

The site of Otford Palace has long been a place of noble settlement. Occupied by the Saxons, it was originally a royal estate that was given as a gift from the monarch to the church during the early medieval period. Over the course of successive incumbents, the palace would be aggrandized. Ultimately, it became THE most splendid residence associated with the archbishopric of Canterbury.

Originally a moated manor house, Otford was part of a circuit of residences visited frequently by the Archbishops of Canterbury and their households. It was closer to London than the Archbishop’s Palace at Canterbury and this made it more convenient for travelling to attend court and other business in London. During the period when it was in the possession of the church, it was also occasionally visited by the reigning monarch, who would reside there as the archbishop’s guest.

That was until 1537 when Henry VIII’s covetous eyes alighted upon the palace. In short order, Henry managed to wrest its ownership from the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer gave the palace up reluctantly and from this point forward, Otford Palace belonged again to the Crown.

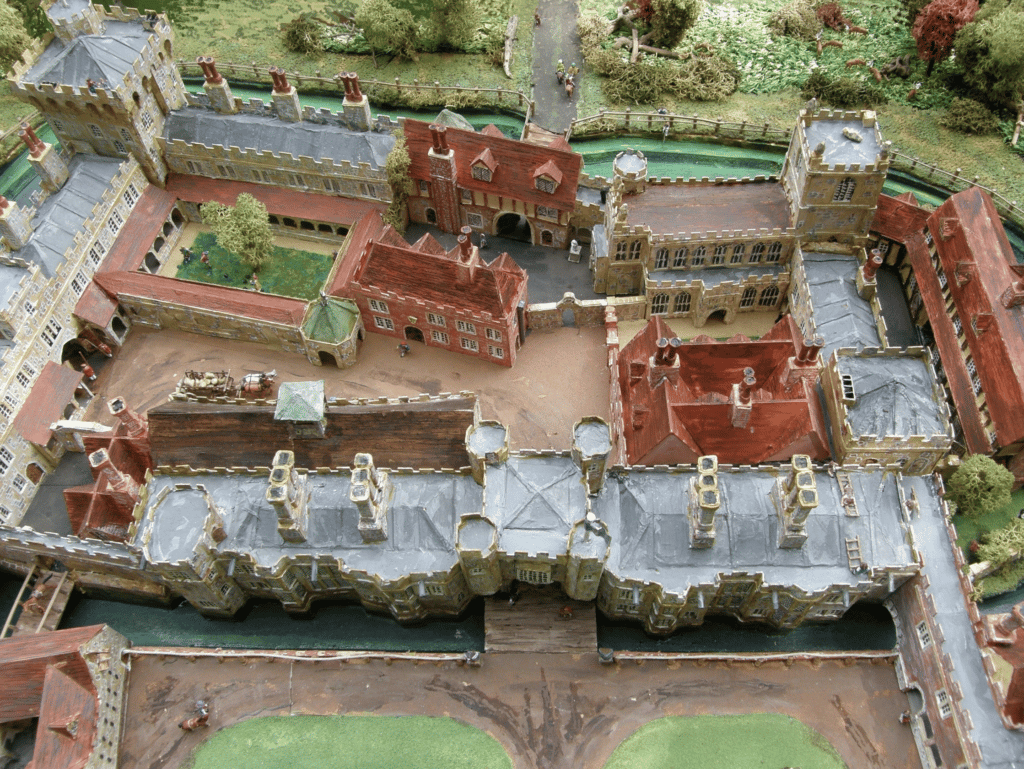

William Warham, who was Archbishop of Canterbury between 1503-1532, was responsible for converting the early manor house into a sprawling complex, which in its heyday was larger than that of his rival Thomas Wolsey’s house, Hampton Court Palace. Both were augmented around the same time circa, 1514 to 1515, although Otford Palace was completed first. At this point, William Warham was both Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor. He later wrote that: were ruinous by neglect, but now sufficiently repaired and enlarged and a great house has been built with galleries and towers, and various new gardens have also been created.

The Palace was approached from the tiny village of Otford by a track that led to an enormous outer gatehouse. Only a small portion of this gatehouse survives: the ground floor of the western part of the gatehouse tower still stands and served the local community as a communal space until recent times. If you walk along the current track that runs to the left of a row of cottages, you will be walking under what was once the passageway beneath the gatehouse arch. Partway along, you will see a bricked up doorway on your right. This once led to the guard chamber. It would have been here that your suitability to enter the palace, your credentials, would have been checked by the guards on duty.

Unfortunately, for us, the gatehouse collapsed in the eighteenth century, leaving only the fragment which survives today. A digital reconstruction of this range (see above) helps us reimagine how the gatehouse would have looked back in the day.

Beyond the gatehouse was the large inner courtyard, which measured roughly 78 m by 270 m. It was trapezoid in shape and you can still see the raised plateau of ground which originally made up part of the palace, although today, the most easterly part of the original courtyard lies beyond a hedge, in private property.

Running around the edge were four ranges with ground floor cloisters. The remains of one of these ranges can be seen in the surviving cottages. This range of buildings once formed part of the north range at the palace. It is easy to see the 11 arches which are now bricked up but would have, originally, been open to the elements.

Thus, adjoining the main gatehouse on either side were two-storeyed galleries that led to two octagonal towers. These marked the northeast and northwest corners of the immense outer court. The north-west tower still stands and is the most striking feature of any visit to the remains of the palace. It has recently gone significant restoration work to save it from decay and collapse.

Flanking each of these towers and running in a southerly direction were two more galleries: one on the west side of the palace and one on the east. The eastern gallery overlooked the kitchen garden, beyond which stood the domestic offices. On the opposite side of the outer courtyard, in the west range, there was a gallery with twenty-one adjoining chambers at ground floor level, used to house the archbishop’s extensive household.

On the first floor, directly above these chambers was the Privy Gallery for use by the archbishop or visiting royalty. This west range of lodgings overlooked the palace’s splendid formal gardens, in which kings, queen’s archbishops and great men and ladies of the ladies passed time in each other’s company.

Directly across from the outer gatehouse, on the other side of the outer courtyard, was the inner gatehouse. This gave entry to the smaller, second court and the principal buildings of the palace that occupied the moated site of the pre-Tudor manor house. A wooden bridge connected the outer court to the great gallery. Beyond this great gallery was a complex of buildings and little courtyards, including the medieval great hall, chapel and the state apartments used by the archbishop, king and queen.

Royal Visitors at Otford

So, just who can we associate with Otford? Well, Warham’s episcopal mansion played host to royalty on a number of occasions; Henry VIII visited in August 1519 and again on 21-22 May 1520. Alongside him was his first wife, Katherine of Aragon. The royal couple and their vast entourage of around 4,000 people were on their way to France to meet Francis I, a gathering that would later become known for its magnificence as The Field of Cloth of Gold.

Clearly impressed by Warham’s newly built palace, Henry returned in May 1522 and again in September 1527. In 1532, after the archbishop’s death, the eleven-year-old Princess Mary spent two summers at Otford.

In addition, Erasmus and Holbein were regular guests and it is worth noting that Thomas Cranmer penned at least some of his Book of Common Prayer while at the palace.

Of course, as we have already mentioned, Henry took possession of Otford very shortly after Jane Seymour’s death in 1537. Perhaps the last great event we might associate with Otford during Henry’s reign was the fact that it was at Otford, in early October 1544, that Katherine Parr was reunited with the king after his return from a military campaign in France; a campaign which had seen the capture of Boulogne. It would be Henry’s last military triumph.

Henry was clearly very fond of Otford. Between 1541 and 1546, the king spent large sums of money on repairing the buildings and maintaining the fishponds, parks and gardens there. Despite this, within two years of Henry’s death in January 1547, when the Crown lost interest in the site, the mighty Otford Palace started to fall into decay – and even by 1570, its ruin was already being noted: In a book called, ‘A perambulation of Kent’, written in that year, its author notes: ‘whereof the olde hall and chapelle onely doe one remaine’.

Visiting Otford Palace today

The car park is within easy walking distance of the centre of the village – a large duck pond, around which cluster shops, a tea room, pubs, the parish church and a driveway that leads toward the remains of the palace. This is not quite on the alignment of the original entrance to the palace, which lies some meters to your left, and would have run just in front of the church.

You can walk around the remains of the north range (bearing in mind, people now live here!) and stand in the centre of what was once the outer courtyard.

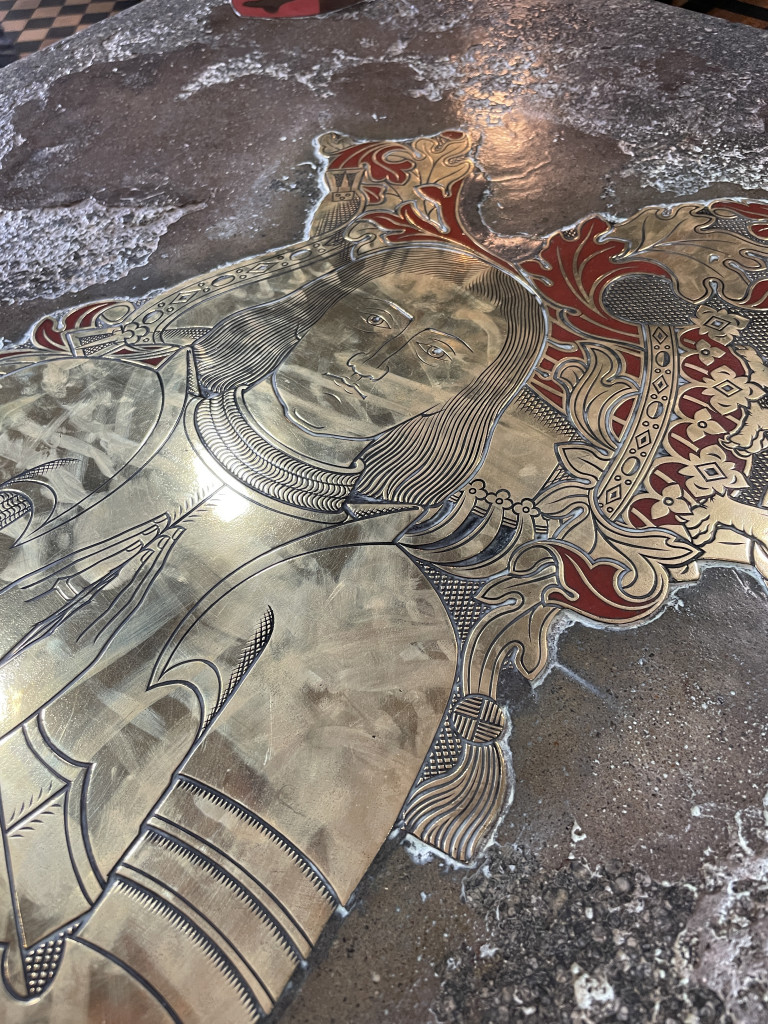

I also recommend a visit to St Bartholomew’s Church, where you’ll find an ornate sixteenth century Easter sepulchre. Note the Tudor roses, and on one of the spandrels, a pomegranate – the badge of Katherine of Aragon.

And finally, what day out in the English countryside would not be complete without taking tea and you will be pleased to hear that although a small village Otford is reasonably well furnished with tea rooms and pubs for the weary traveller, I can recommend a fab little tea room, tucked away at the back of a charity shop called, Hospices of Hope. The main car park for the village is situated just off the High Street. It makes for a convenient place to park up and explore the village and the historic, Tudor ruins of a once-great house that was forged in rivalry, enjoyed its brief moment of glory, before falling into ruin within a space of just 70 years. Unbelievable!

One Comment