Mary Queen of Scots: A Glittering Future at the French Court

All I can tell you is that I account myself one of the happiest women in the world. These words were written by the fifteen-year-old Mary Queen of Scots on the morning of her wedding to the Dauphin of France in 1558. It is almost impossible to believe that these sentiments are associated with the person whom we now associate with a desperately tragic life. To commemorate the anniversary of Mary Queen of Scots’ fateful execution at Fotheringhay on 8 February 1587, we welcome a new guest author and young historian to The Tudor Travel Guide: Katie Marshall. Katie will be sharing the story of Mary’s early years in France, possibly the happiest time in her life. Along the way, we will visit several glorious and historic places in France linked to the Scots Queen. So, it’s over to Katie!

Mary, Queen of Scots Leaves Scotland

In the true spirit of Mary’s adopted motto, which she embroidered onto her cloth of state not long before her execution ‘En ma Fin es mon Commencement’ (In my end is my beginning), I hope to bring to life some of the places in France linked to Mary, Queen of Scots. These places are part of Mary’s less widely discussed, early years. A vivacious young queen with a future of limitless possibilities, Mary lived in France until the age of eighteen. It was later, after her return to Scotland to claim her throne in person, that she became entangled in the cut-throat politics of the country. This return also eventually led Mary, Queen of Scots miserable nineteen years as a captive.

Before her departure to France, when Mary was aged just five-and-a-half, she resided in the safety of Dunbarton Castle. Situated beside the River Clyde, it was a stronghold with the longest recorded history in Scotland. It was from here that Mary boarded the galley that would transport her to France, beginning a new chapter of her eventful life.

The sudden death of Mary’s father, James V, was followed by a complex series of religious and political divisions. This, coupled with the relentless pursuit of England’s destructive ‘Rough Wooing’ policy (in which Henry VIII pushed for the alliance between his young son Edward and the Scots Queen), meant that Scotland was an increasingly hostile environment for the infant queen. In light of this, Mary’s mother arranged, behind England’s back, to send her daughter to France to be brought up in the sophisticated French court. It was hoped that she would one day wed the heir to the throne, securing French support against the English. Bidding an emotional farewell, Mary embarked upon her journey. It quickly proved to be terribly long and rough, with the majority of the crew suffering from violent seasickness – all, it seems, except the young queen. Instead, Mary is recorded to have carried herself with admirable dignity, having remained unaffected by the riotous seas.

She was accompanied by her ladies in waiting, famously known as her ‘Four Maries’, whom she had befriended during her days at the Island Priory of Inchmahome. One of the first places Mary stepped upon French soil was at the Port of Roscoff, Brittany. Here, Mary and her retinue may have visited the chapel in order to express thanks for their safe arrival. It was later named after the Scottish Saint Ninien in commemoration of her disembarking here. The chapel has since fallen to ruin, however, what is said to be the original arched entrance, and font, can now be seen incorporated into the wall of one of the seafront houses

Mary Queen of Scots and the Chateau of the Loire Valley

Throughout her thirteen years in France, Mary, Queen of Scots mainly spent her time in the numerous palaces that sit on perimeters of the Loire Valley*. It is generally thought that Mary’s education, within the French royal household, was carried out at the Château d’Amboise. Although thousands of miles from her Scottish birthplace of Linlithgow Palace in West Lothian, the surroundings at Amboise were deemed to loosely resemble those at Linlithgow. Mary’s mother, the French noblewoman Marie de Guise, had favourably compared the luxuriously renovated Scottish Palace, which had been one of her favourites, with the Loire Château. Both were pleasure palaces surrounded by scenic waters.

Despite its serene exterior, Amboise was where Mary would later experience some of the most sinister times that she spent in France. Once Mary’s husband had ascended the throne in 1560, it was here that Huguenot plotters attempted to storm the château. This was one of the most significant events that led to the French Wars of Religion – a period that divided France from 1562-1598. Mary, someone who had a light stomach in the face of violence, if not fully witness to the events, would have been aware of the infamous brutality associated with them. The failed coup involved between 1,200-1,500 members. Their corpses were subsequently hung on iron hooks on the façade of the château and from nearby trees. Others were drowned in the Loire or left to suffer the wrath of the mob of angry townsfolk.

*see the end of this article for more information on the places in France linked to Mary Queen of Scots. Some of the châteaux can still be visited today.

A Cuckoo in the Royal Nest?

At Carrières-sur-Seiene, a few miles from St. Germain, Mary arrived to take her place in the French royal nursery. She was now in the care of King Henry II of France and his wife, the formidable Catherine De Médici. During that time the question of Mary’s status, already a Queen Regnant in her own right, arose within the royal nursery. This was a contentious issue, especially considering that the royal nursery was expanding and already included a daughter, Elizabeth de Valois, who was only a few years younger than Mary. The issue was settled through the guidance of none other than Diane De Poitiers* when it was agreed that the young Mary would be second only to the Dauphin, Francis. She enjoyed a sibling-like relationship with the other royal children, sharing one of the best bedrooms with Princess Elizabeth, aged three and a half.

*Henry II’s influential long-term mistress whose position, despite Catherine De Medici’s irritation, allowed her to exercise a great deal of power within domestic politics. In the age which saw a resurgence of interest in classical references, Diane aligned herself with Roman goddess Diana (equivalent to the Greek Goddess, Artemis) and adopted the crescent moon as her emblem. It was even said that Henry II often chose to wear black and white, colours closely associated with Diane, in order to signify his devotion to her.

Mary first met Catherine De Medici, the French Queen and her soon-to-be mother-in-law, at St. Germain. Like the majority of French courtiers, Catherine could not help but admire Mary’s charming nature, exclaiming ‘our little Scottish Queen has but to smile to turn all French heads’. Despite acquiring a royal future daughter-in-law, Catherine was fiercely protective of her own children’s inheritance and deeply resented the interference of the highly political De Guise family who aligned themselves, naturally with the Scots Queen. After Mary had settled in, Catherine reportedly approached Mary on one occasion to ask her why she failed to bow to the Queen of France. To This, Mary is said to have responded ‘Why do you not bow to the Queen of Scots?’ Rumour has it that Mary was under the impression that Diane De Poitiers was really the King’s wife! It is an enticing, albeit possibly fictitious, dialogue but it nevertheless accurately points to the young Mary having had an intrinsic sense of her own grandeur. Totally unfazed by the potentially intimidating situation she found herself in, she was totally self-assured.

It was not long before the French King, Henry II, was referring to Mary, Queen of Scots as ‘my very own daughter’, whilst maintaining that she was ‘the most perfect child’. It seems likely that as a child, Mary received an abundance of love and adoration, making the later events in her life even more painful.

“Her mouth is too large and her eyes too prominent and colourless for beauty”, wrote a Venetian envoy as Catherine approached forty, “but a very distinguished-looking woman, with a shapely figure, a beautiful skin and exquisitely shaped hands”.

Mary, Queen of Scots: A Cultured Upbringing at the French Court

Sixteenth-century France was a magnet for Renaissance culture, so Mary was exposed to the height of European fashions, both in dress and attitude. Her education was exceptional. Among her tutored subjects she was schooled in languages. In addition to the necessary French, she was taught Latin, Italian, Spanish, and some Greek. Philosophy and rhetoric were considered to be an essential basis for learning the morals of rulership through the study of Plato, Aristotle and, presumably, classical literature.

Mary spent the majority of her time in the classroom. She is widely known to have adored outdoor sports, singing, dancing and playing musical instruments. Her talents in music and languages, in particular, became a cause for later rivalry with her counterpart, Queen Elizabeth I. When James Melville, the Scottish ambassador, travelled to Elizabeth I’s court on a diplomatic mission, he was unexpectedly met with enquiries from a curious Queen Elizabeth on who was superior in looks, language skills and ability to play the virginal!

Elizabeth I of England and Mary, Queen of Scots.

The two ‘sister queens’ were alike in so many ways, notably in their approach to rulership, but their situations had momentously crucial differences. When Mary later returned to Scotland, they exchanged countless heartfelt letters and gifts, for they alone could understand each other’s struggles in being a Queen regnant, in spite of never meeting each other in person. Elizabeth was forced by her councillors, with crippling reluctance, to finally sign her cousin’s death warrant in 1587.

Reunited in Rouen

At Rouen, in October 1550, Mary was to be briefly reunited with her mother, Marie De Guise, during the royal entry, staged with the purpose of celebrating the expulsion of English troops from Boulogne. At the same time, this promoted the imperial glory of the French monarchy. While her move to France had already strengthened Mary’s bond with the maternal branch of her family, she was nevertheless overjoyed at the prospect of seeing her mother, after an absence of three years. In a letter she wrote to her grandmother, Antoinette of Bourbon, Mary expressed that to have her mother visit France was ‘the greatest happiness that I can desire in this world…’ Henry II took the safety of Marie De Guise’s journey into his own hands, making a personal request for her safe passage before sending a French galley to receive her. The visit re-ignited friendship that had long existed between both countries and further cemented the auld alliance.

Henry II saw Mary’s marriage to his son as his ticket to an unparalleled triple monarchy. This satisfied his imperial vision. Not only was his son made King Consort of Scotland, and therefore also a King-Dauphin, the two co-ruling together opened the possibility of uniting three crowns. In the eyes of Catholic Europe, Mary had one of the strongest claims to the English throne. With an ailing Mary I of England childless, speculation on the future of the English succession was inevitable. The obvious candidate for an heir was her half-sister, Elizabeth. However, she was arguably the very embodiment of the break with Rome. Henry VIII, of course, having taken the initiative to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and instead marry Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn. This made Elizabeth’s claim detestable to the majority of Catholics, who saw her as illegitimate and a heretic. Catholic Mary Stuart, was the preferred claim, especially with her having been a great-granddaughter of Henry VII. Marie De Guise, on the other hand, benefited immeasurably from French aid in keeping the situation in Scotland stable during her regency.

At Rouen, the guests were entertained to the most spectacular level. Parading theatrically through the streets, Henry II modelled himself as a triumphant ancient Roman general accompanied by the spoils that he had brought home from war. There were even, according to contemporary accounts, unicorns (grey horses styling horns) and elephants amidst the parade! However, when a mock sea battle was performed at the climax, (bearing in mind that they did this with genuine canons and gunpowder), the outcome was disastrous, resulting in the deaths of almost all of the participating crew members. Determined that the stunt be remembered as success meant that the ships were sent off again in the following days. Tragically, the consequences of this were not significantly different from the first attempt!

A Dynastic Marriage of Nations

On April 19 1558, in the great hall of the Louvre in Paris, Francis and Mary were formally betrothed. Mary’s grandmother, Antoinette of Bourbon, stood in as Marie de Guise’s proxy. Debated issues over independent sovereignty were glossed over publicly. Instead, the focus was set on cementing the alliance between the two nations and the glorious future they might share.

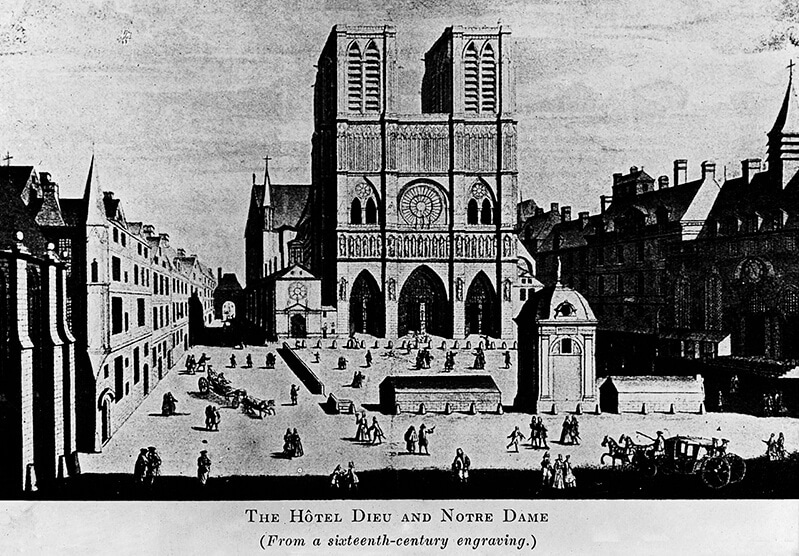

The pinnacle of Mary’s time in France, her eventual marriage to the Dauphin, took place in the capital’s spiritual heart of Notre Dame Cathedral on 24 April 1558. Mary was fifteen and the Dauphin fourteen. All eyes turned to the spectacular occasion, which symbolised the two crowns of Scotland and France being joined in heart and mind. Alongside the political significance of the day, it was Mary’s enthralling appearance that drew everybody’s attention. Courtier, Pierre de Brantôme, described her as ‘a hundred times more beautiful than a goddess of heaven … her person alone was worth a kingdom.’ His words certainly had weight.

Mary is recorded to have worn a breath-taking dress, heavily embroidered with shimmering diamonds, accompanied by a lengthy train of ‘a bluish-grey cut velvet. It was richly embroidered with white silk and pearls and was held by two maids of honour. Even more notable was the colour which Mary had chosen for her dress – it was white. In sixteenth-century France, this would have been a particularly audacious choice. White was considered the colour of mourning for the royal family when they dressed ‘en deuil blanc’. However, Mary was not a woman to be imprisoned by convention. With her bright auburn hair flowing beneath a gold crown, richly bejewelled with diamonds, pearls, sapphires, emeralds and rubies, she must have been simply blinding to the crowds of Parisians that gathered in the sunlight outside the cathedral that day.

A sixteenth century engraving on Notre Dame Cathedral – a sense of what it would have looked like on Mary’s wedding day in April, 1558

Following their wedding, the Valois dynastic dream came to a head, when Mary I of England died on 17 November that same year. However, this was not to be the Catholic-led transition that Henry II had planned and hoped for. Elizabeth – Mary I’s half-sister and Mary’s cousin – was swiftly proclaimed queen, with her accession being met with very little resistance from the people of England.

In desperate attempts to reinforce the strength of Mary as the alternative, Catholic, Queen, it was ordered that the plate of Mary and Francis’ household be shamelessly adorned with the heraldic arms of England, alongside those of France and Scotland. In the new year, the campaign intensified, with official documents to foreign powers being headed with declarations of Mary and Francis as ‘King and Queen Dauphins of Scotland, England and Ireland’. By the summer, the professions had become yet more provocative, with ushers crying out ‘Make way for the Queen of England’ as Mary entered the chapel. In time, this period would be the one most recalled by William Cecil and his allies whenever they wanted to remind Elizabeth of the genuine threat that Mary posed to her security as queen. At this point, however, Mary’s lineage made her a valuable card to play in a political game.

Mary and Francis, depicted in Catherine De Medici’s personal Book of Hours c.1558

This stunning book includes portraits of many members of the royal extended family. Movingly, notably included among these is a combined portrait of her son, Louis and daughters, Jeanne and Victoire, all of whom died in infancy.

It is housed in The Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Mary, Queen of Scots: 1559-1560 – ‘Till Death Do Us Part’

Eight months passed after Elizabeth I’s accession to the English throne and Henry II had turned his attention to celebrating. The outcome of the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis had been a remarkable achievement. It was a landmark which brought a sixty-five-year power struggle between France and the Spanish Hapsburgs for dominance over Italy to an end. The peace was sealed with the marriage of Henry and Catherine’s eldest daughter, and Mary’s close childhood friend, Elizabeth, to King Philip II of Spain. He had become a widower upon the death of Mary I of England.

In his enthusiasm, the French King insisted upon rematches of a joust against the Count of Montgommery. Considering that this was an extremely high-risk sport, which had put Henry VIII’s life in danger on several occasions, Catherine and Diane pleaded with him, in vain, to concede defeat. Ever competitive, Henry refused and went ahead with the joust. The King was left with the most unimaginable injuries due to his helmet being shattering by his opponent’s lance, causing untreatable damage to his brain.

Like the rest of the royal court, Mary and the Dauphin were left shocked and bewildered by what had happened, as they stood around the King’s bed in the Hôtel des Tournelles. On 10 July 1559, Henry II died of a stroke. Mary and Francis found themselves catapulted onto the French throne, with Mary being just five months short of her seventeenth birthday. She was now not only Scotland’s Queen but also Queen of France.

Members of the Royal court gathering around Henry II’s deathbed the Hôtel des Tournelles. This had been where Henry II had also celebrated his coronation in 1547. Following her husband’s death, Catherine de Medici initiated the building’s demolition, partly due to her dislike of its medieval appearance.

The next two months must have been like standing in no man’s land for the royal teenage newlyweds. Little did Mary know that the hope of a new era would soon be thwarted; the first of the significant tragedies of her life was waiting just around the corner.

Francis II was crowned in the holy surroundings of Rheims Cathedral on 21 September 1559. He was dressed in a blue velvet gown trimmed with ermine and golden fleurs-de-lis. Mary watched on as her uncle, Charles, also Archbishop of Rheims, anointed and crowned her husband during the time-honoured ceremony – it is said to have lasted over more than five hours! In a respite from the formalities, the keeper of the royal aviaries released around eight thousand songbirds from amidst the choir as they sang the evocative Te Deum, a visual expression of peace and hope for the new age.

Mary was likely distracted by thoughts of her home country. The situation there, at least from a Catholic point of view, was dire. Mirroring the public mood in France, Scotland was shifting evermore to embrace the Protestant faith. In fact, it was happening at an astounding rate, helped along by sermons delivered by fervent preachers recently returned from Genevan exile. The most prominent of these, John Knox, also ardently believed female rulership to be an insult to God. As regent, Marie De Guise worked tirelessly to keep Stuart authority afloat, facing the revolting ‘Lords of the Congregation’. However, their grip was too firm and her health too fragile. With their organisation seamless, on the 19 –23 October the rebel lords, among whom was Mary’s half-brother James Stuart, overthrew Mary’s mother and installed themselves as the leading authority of Scotland.

At the height of the crisis and suffering from both mental and physical exhaustion, Marie De Guise’s health hung in the balance. Defying the advice of her French doctor by insisting on mustering yet more troops, Marie succumbed to complications of lymphedema on 11 June 1560, whilst at Edinburgh Castle. The news of her death was to be kept from her daughter, now Queen of France, for several weeks.

When Mary was eventually informed, she was devasted at the news. She had become close to her mother, particularly so due to the constant presence and guidance of her mother’s Guise relatives at the French court. England took this opportunity of constitutional crisis in Scotland to press Mary into accepting Elizabeth as England’s Queen. However, Mary found the request to renounce her claim to be insulting. The Treaty of Edinburgh was a formal acknowledgement of the rebel Scottish Reformation Parliament, which had so recently deposed her mother.

Sadly, 1560 had yet more bad news in store for Mary. Francis had shown signs of physical weakness from an early age. Reportedly, he looked particularly short for his age. His short stature was even more pronounced against Mary’s towering physique; she was around 5ft 11 tall. In December, Francis’ strength gave way to an infection which, in the absence of modern antibiotics, soon became an agonising abscess on his brain. Mary sent for her own French doctor, who happened to be a Huguenot, but his distraught mother, Catherine, would not allow the intrusive operations recommended by the physicians to go ahead. Francis died on 5 December 1560. After a brief reign as queen consort that lasted just seventeen months, Mary now found herself as an orphan, a widow and Queen Dowager of France – all at the age of eighteen.

After adhering to the customary 40 days of official mourning for both her mother and her husband, Mary faced up to her options. She could either enjoy a comfortable life in France and possibly remarry a suitor of Catholic European royal stock, or she could take the bold move to return to her now Protestant nation, which she had left at the age of five, as its Catholic Queen.

Mary set forth into the next chapter of her life with a genuine desire to gain the trust of her cousin, Queen Elizabeth, who she described as ‘the nearest kinswoman that each other had’. She was keen to cultivate a policy of religious tolerance in her homeland. With this in mind, Mary made arrangements to leave her home of the past 12 years. She was ready to claim her Scottish birthright. With her galley mooring at Leith on 19 August 1561, the public was thrilled to have their queen back on Scottish soil. She would soon realise, however, that she would quickly have to adapt from being a Frenchwoman to a Scotswoman if she were to survive!

More Information

It is still possible to visit some of the places in France linked to Mary, Queen of Scots. These are locations that Mary would have known well. They are intact and can be visited:

Blois – includes the only French Renaissance study room still intact today, along with 180 sculpted oak panels in the ‘Queen’s study’ which date back to the 1530s.

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye – situated twelve miles west of Paris, this stunning château is where Mary will have spent much of her childhood in the company of the Dauphin. It is also said to be where the young Mary first met the French Queen, Catherine De Medici.

Palace of Fontainebleau – the birthplace of the Dauphin, who became Mary’s first husband. Henry II, as well as Catherine De Medici in later years, carried out significant renovation and extensions on the château which still stands resplendent today. This is where Mary departed French court life to begin a tour, bidding a final farewell to her Guise relatives, before embarking on her voyage back to Scotland.

Château de Chambord – being the largest residence of the Loire, Chambord is the height of the royal grandeur and typical of French Renaissance architecture. Among those responsible for its design, it is said that Leonardo Da Vinci initiated the original reconstruction in 1519, under Francis I. This influence is particularly clear in the staircase, which is of double-helix design. This meant that people, simultaneously climbing and descending the stairs, never meet. This château a very popular choice for visitors seeking to absorb both the scale, as well as intricate detail, of the building.

Château d’Anet – a residence originally built for the Henry II’s mistress, Diane De Poitiers. Following the King’s death, it was to this location that Catherine De Medici banished the woman who had stolen her husband’s heart. It was also a favourite retreat for the royal children during Mary’s time in France.

Château d’Amboise – this royal château saw a lot in Mary’s time, most likely having been the setting for some of Mary’s happiest, and most traumatic, days.

The Tudor Travel Guide welcomed Katie Marshall as guest author for this article. Katie is a historical researcher, with a particular interest in Elizabeth I and the Tudor court, and Renaissance portraiture. Katie engages with other researchers and historians who share her passion, attending courses and discussions and reviewing books and videos in these areas. Alongside her historical interests, Katie is a Classic BRIT Award-nominated Soprano who has performed around the UK and overseas, having had the opportunity to work with many acclaimed musical directors and composers, performing in many historic locations. You can connect with Katie on Twitter via @katiehistory.

Gallery of Images – Château de Chenonceau

This gallery of images was compiled by The Tudor Travel Guide, and all images are the author’s own.

This gallery of images is associated with a podcast episode in The Tudor History & Travel Show. To listen to the episode click here.

If you are listening to the shorter version of the podcast, you will end your journey just before the artefact in Francis I’s bedroom is revealed. For the patron only episode, the episode journeys through the entire gallery of images below. For more information on accessing the full podcast, click here.

Main Entrance & Guard Chamber

The Great Gallery

Closet

Grounds & Gardens

Diane de Poitiers Room

The remainder of our journey is available only through the patron only episode.

Francis I Bedroom

Five Queens Bedroom

The Chapel

Such an interesting blog – thanks very much!

Pleased I found this, it was fascinating! Thanks for the mention of places to visit in France ????

Brilliant detail into Mary’s early days. I wish Scottish School history had such details on our Kings and Queens

Wonderful information on the Quee whose life was so sad and who was greatly slandered in her lifetime

Womderful article. Thank you. I live in Amboise 5 mins walk from the Chateau. Do visit me! You will be very welcome. We can talk French history all day! Pamela Shields http://www.photographfrance.com

Hi Pamela! How wonderful for you! I love Amboise and indeed might be paying a visit this coming summer ?.

You never know…we might get to meet.

Absolutely brilliant! I love Cws Reign and had to delve into the true life of Mary, Queen of scots. I recently traced some lineage back to 15th century scotland, hoping to confirm accuracies for Scotland has long been in my heart.

Thank you so much for this Travel Guide. I visited much of central France in August and September of 2022, including Chambord (which I abhorred!) and Chenonceau (which I adored!). Completely different reactions in two days. I plan to return to Amboise to visit Chenonceau again and the Castle, about which I have read much. I find myself becoming a serious, though amateur, historian of and writer about France. My main interest is the 16th century. Have studied French for years, and visited 5 times. Will return a 6th time this spring. Would love to contact anyone here living in France, and/or with similar interests.

Bonne chance à tous!