Kenninghall: A Magnificent Tudor Time Capsule

How would you like to explore a Tudor time capsule? Kenninghall is one such place, even though there is little left to see today, and the time capsule must exist only in your mind’s eye. However, once upon a time, it was the principal country residence of the mighty Howard family, including its head, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. But why is this place so special if there is nothing more to see than a small fragment of the building incorporated into a modern-day farmhouse?

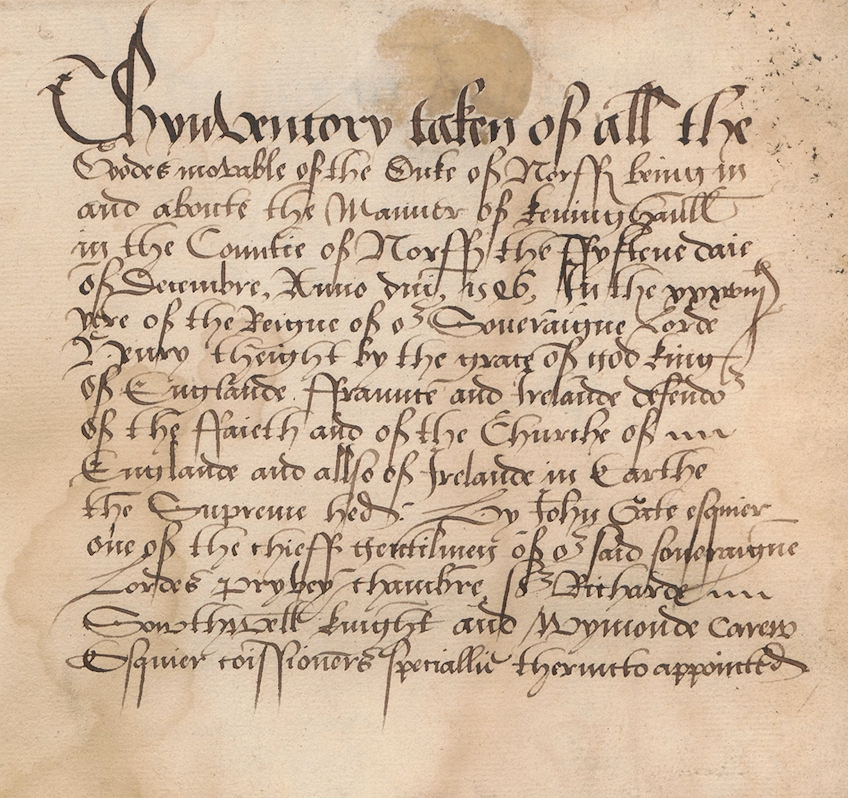

The answer lies in the extraordinary events which befell the Howard clan on Sunday, 12 December 1546. On that day, the Duke and his eldest son, another Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, were arrested on charges of high treason and sent to the Tower. On the same day, three royal commissioners, John Gate, Sir Richard Southwell and Wymond Carew, were dispatched, all haste, from the Council in London to the Howard residence at Kenninghall, in Norfolk. Their job was to seize and make an inventory of all the Duke’s goods and those of the other family members who were in residence at the time.

I have long wanted to learn more about Kenninghall but found little online until I came across the work of the historian, Nikki Clarke. Nikki is a Senior Lecturer in Medieval & Early Modern History at Chichester University. I will talk to her about Kenninghall in this month’s Tudor History & Travel Show as she is particularly interested in the Howards – and Howard women. It was her blog that made me aware of the existence of the Kenninghall inventory. After having invested a substantial amount of money to get a copy from the National Archives in Kew for myself (!), my prayers were answered. Thanks to one of the most complete inventories taken during the period (which runs to 145 pages), we are treated to a lavish record of a house frozen in time. It is AMAZING!

I am still learning to read old English. So, deciphering the inventories was challenging, and I have yet to figure out some details! However, determined, I managed to work through the main headings, which list the rooms of Tudor Kenninghall. In time, I hope to revisit this blog and enrich it (or even write another one) with more detail about the items found in each room.

The Commissioners are Dispatched

Having left London between 3-4 pm on Saturday, 12 December, the commissioners record in a letter to the King’s Council that they reached Thetford, ‘seven miles from Kennynghall’ on Monday. Completing the last leg of their journey, they finally arrived at the Duke of Norfolk’s house the following morning (the 14 December) at daybreak, ‘thus bringing the first news of the Duke and his son.’

As we will hear, the household was quickly secured, the three men ‘taking order of the gates and back doors’ before the two principal ladies of the house, Mary Fitzroy, Duchess of Richmond and Bess Holland, the Duke’s longstanding mistress, were called to meet with the three men in the dining chamber. They had only just arisen from their beds.

Hearing of the news of her father and brother, Mary was ‘sore perplexed, trembling and like to fall down’. However, she recovered and, dropping ‘reverently upon her knees, humbled herself to the King, saying that although constrained by nature to love her father, whom she ever thought a true subject, and her brother, “whom she noteth to be a rash man,” she would conceal nothing but declare in writing all she can remember.’

As with Wolsey’s arrest at Cawood (where we have another florid description of what came to pass), it is likely that the household, from the highest to the lowest, was kept under close watch while the house was thoroughly searched, and an inventory taken of each chamber and its contents. With the household taken entirely off-guard, there was no time to squirrel away any household contents. So, the record we are left with from that day is priceless!

Kenninghall: A Stately Mansion

Kenninghall lay directly west of the Thetford. Before the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was home to Thetford Priory, containing the mausoleum of the Howards. Henry Fitzroy, the young Duke of Richmond and Mary Howard’s late husband was buried there in 1533. Of course, on account of the Dissolution, Fitzroy’s tomb, and eventually those of the 3rd Duke and the Earl of Surrey, ended up at the new family mausoleum at Framlingham Church, in Suffolk, adjacent to another Howard stronghold – Framlingham Castle.

About one mile from the nearest town, Kenninghall was surrounded by a 700-acre deer park, with woodland and groves protecting it on its north side. There had been a house of significance on the site since Anglo-Saxon times, with Kenninghad meaning ‘King’s House’. At the time of the inventory, there is a record of the house being arranged in an ‘H’ Shape (‘H’ for ‘Howard’ possibly?) with a central cross-range connecting two other ranges running north-south. One of these faced east and the other west.

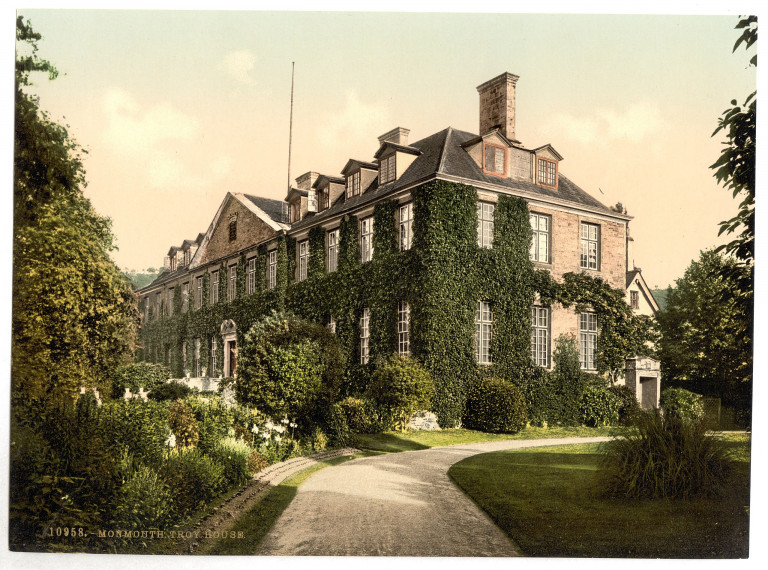

The inventory also clarifies that most of the principal ranges had three storeys. The remains of Kenninghall today (see image below) are brick-built with the typical Tudor diapering pattern evident on the gable end, indicating how the house’s exterior once looked.

Although we do not know the exact floorplan of the house from the inventory, the commissioners seem to have worked their way logically through the house, recording each chamber and its contents meticulously as one room followed another. This leaves us with at least some clue as to its overall layout.

The Kenninghall Inventory

According to the inventory, the chapel was the first target of the commissioners’ attention. Here we have items listed in the body of the church and the belfry (where numerous copes, canopies and altar clothes were found). Three further chambers are recorded as adjoining the chapel. Nikki Clarke notes that these chambers accommodated the priest, master of the children (the choir) of the chapel and the choir themselves.

Norfolk’s chapel at Kenninghall was particularly extensive and well-endowed, with only the most wealthy and prestigious able to keep an entire chapel retinue as part of their private household. Another household that comes to mind (outside of the King’s) was Margaret Beaufort’s, who kept a similar arrangement at her primary country residence at Collyweston, in Northamptonshire.

Continuing with the inventory, oddly, the nursery is listed next. From John Gate’s letter to the Council in London, we know that Lady Surrey (the Earl of Surrey’s wife) and her children were in residence when the commissioners pitched up at the front gates of Kenninghall. He mentions them in passing after the inventory has been taken and plans were well underway to ship off the Duchess of Richmond and Bess Holland to London for questioning.

In the letter, he states, ‘Now that only the Earl of Surrey’s wife and children, and certain women attending upon them in the nursery, remain here, it is to be known whether the household shall not be partly dissolved, reserving such as seem meet to attend upon the Earl’s wife, who looks to lie in at Candlemas next.’ Francis, Countess of Surrey, was over seven months pregnant with her fifth child at the time. Goodness knows how she must have been feeling!

The washhouse is listed next, perhaps this was part of the outer courtyard and the service buildings associated with the house; pages listing linen, tablecloths and napkins are recorded. The Great Hall follows and is noted to contain, amongst other items, tables and cupboards, presumably used for displaying plate. Although we cannot say so for sure, it might be expected that the great hall occupied the cross-range of the ‘H-shaped’ building, as was frequently the case with Tudor houses of the same scale as Kenninghall.

At the first floor level (‘the second’ according to the Tudors – and also our modern US friends!) we learn of the Great Chamber, presumably, a kind of presence chamber, where the Duke would have formally received visitors and heard petitions. This sat directly above the ground-floor chapel and seems to have led into a dining chamber or privy chamber, just as we would expect in a high-status house. It was in the dining chamber, of course, that Gate and his companions’ letter tells us that he had his first encounter with the Duchess of Richmond and Bess Holland.

The inventory also tells us that the usual sequence of privy rooms existed at Kenninghall. This is clear from the next set of rooms recorded; those of the Duchess of Richmond, who had not only a privy (outer) chamber but a bedchamber, inner chamber, a closet and a chamber for her maid, apparently adjoining her rooms. Close by, and perhaps linked to the Duchess’ chambers, was the ‘Press Gallery’. Nikki Clarke postulates that, presumably, this contained presses for keeping clothes. According to the commissioners, having searched Mary’s lodgings, they ‘find nothing worth sending, all being very bare and her jewels sold to pay her debts’. Poor Mary!

On the floor directly above Mary Fitzroy’s lodgings were those of the Duke of Norfolk himself; an outer chamber, bedchamber, an inner chamber and closet are listed. Numerous other chambers are also noted at this point. Nikki Clark states that ‘to judge by their contents, one was used by his son the Earl of Surrey, and another (‘the inner chamber’) by his mistress Elizabeth Holland’. What is most breathtaking, though, are the pages and pages detailing the clothing, jewels and plate being kept by the Duke at Kenninghall; gold, rubies, diamonds and garnets set in collars, rings, billaments and brooches. One day, I will transcribe the whole lot! And, let’s remember that Kenninghall was not the only property belonging to Thomas Howard. What is listed there, is indicative of just a fragment of his wealth.

On the floor above the Duke’s was his mistress’ lodgings. These stacked lodgings had been fashionable in the early sixteenth-century and perhaps Bess, who had been in a relationship with the Duke for some 20 years, had long since occupied the Duchess of Norfolk’s chambers. An outer chamber, bedchamber and her maiden’s chamber are listed, followed immediately by a ‘garret’ and a ‘turret’ room ‘at the short gallery end’. All these rooms seem to have been easily accessed by, or part of, Bess’ lodgings at Kenninghall. A ubiquitous long gallery is also listed alongside the ‘Short Gallery’. The long gallery is noted as having a closet at one end.

Bess Holland had more to lose from the Duke’s downfall than his daughter, Mary. While the Duke seems to have allowed Mary to slip into relative poverty, this was far from the case with Bess. The inventory makes it clear that she had been generously endowed by the Duke. However, not only were her rooms turned upside down but according to the commissioners’ letter, Gate and his men even searched Elizabeth Holland herself (‘then searched Elizabeth Holland’ – although I do wonder if this is meant to read, ‘then searched Elizabeth Holland’s rooms’). Regardless, they found ‘girdles, beads, buttons of gold, pearl and rings set with divers stones’. Gate records that ‘a book is being made’ listing all her possession and that ‘trusty servants’ had been dispatched to a new house that had been given to her by the Duke in Suffolk and which was thought to be ‘well-furnished’.

In another part of the building, on the ground floor and off a courtyard called the ‘Ewery Court’, were a whole host of service offices and lodgings for various household officers. On the first floor (the second story, according to the inventory) was the Earl of Surrey’s lodgings: ‘The Lord Thomas” chambers, as well as ‘The Lord Howard’s’ Chambers’ (possibly belonging to another member of the Howard family). Surrey’s lodgings were also extensive: an outer chamber, inner chamber, upper chamber and bedchamber are all recorded. In the same part of the building, the ‘Old Garderobe’ [Wardrobe] and the ‘Old Chapel’ are also mentioned. This hints at the layout of the old house, before the 3rd Duke’s extensive renovations.

Meanwhile, Back in London…

Meanwhile, around 100 miles away in London, Thomas Howard was finally getting a taste of his own medicine. As his properties and possessions were being seized and his lands and titles being confiscated, he wrote to Henry VIII, begging for the king’s grace. At the same time, from a cell somewhere nearby, Surrey is writing to the Council, requesting that they hear his case directly. They do not know that the Duchess of Richmond and Bess Holand will soon be shipped to London to give evidence against her father, brother and lover. The cogs of the Tudor state had begun to turn against them, and the outcome was almost inevitable.

Surrey was executed, having been found guilty of treason on Tower Hill on 19 January 1547. Norfolk, that wily Duke who had presided over the death of his niece, Anne Boleyn, danced with death. However, he nimbly avoided a date with the executioner only on account of the fact that Henry VIII died the day before he was due to walk to the scaffold. Nevertheless, Kenninghall was forfeit and handed over to the Lady Mary (Henry VIII’s daughter), thus adding to her estates in Norfolk and Suffolk. Interestingly, the house would play a central role six years later at a critical moment in Mary’s story.

Mary Declares herself Queen at Kenninghall.

During the tense two weeks after the death of Edward VI, when Lady Jane Grey briefly felt the crown of England touch her head, Kenninghall was once again at the centre of the action. Mary was fond of the house and fled there, having heard of the plot to seize her by the Duke of Northumberland and the Council. She arrived on 9 July 1553. Mary had been joined along the way by increasing loyal followers. Once at the house, an armed camp grew up around the grounds and lands immediately surrounding Kenninghall.

Shortly after her arrival, Mary received confirmation that the rumours of her half-brother’s death were true. She gathered the household in the abovementioned great chamber and declared herself the new Queen of England. Excellent news for the Catholic Duke of Norfolk, still waiting in the Tower! He was soon released and officiated at Mary’s coronation on 1 October 1553. His last engagement on behalf of the Crown was to play his part in suppressing the Wyatt rebellion in 1554. However, no doubt weary of court life, Thomas Howard crawled back to Kenninghall and died there in his bedchamber on 25 August 1554.

After the 3rd Duke’s death, Kenninghall passed to his grandson, the new 4th Duke of Norfolk, who spent time at the house before his execution in 1572. According to Blomefield: ‘It continued in the Norfolk family as their capital seat in this county, till about 90 years since [circa 1650-1700], when it was pulled down, and the materials sold for a trifle, with which great numbers of chimnies and walls in the neighbourhood are built, as is evident from the Mowbrays and Arundels arms which are upon the bricks.’

All that remains today is part of a service range incorporated into a farmhouse, ending another great Tudor house. But let us at least be thankful that, unlike so many others, the Norfolk’s misfortune of 1546 was our good fortune and that the Kenninghall inventory has left us with an incredible picture of a magnificent Tudor palace frozen in time.

Sources:

The Kenninghall Inventory. The National Archives (LR 115, 116 and 117)

Frock N’Scroll: A blog by Nikki Clarke, Kenninghall Inventory 1546 – Part 1

The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII

An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 1, by Francis Blomefield. Originally published by W Miller, London, 1805.

I’ve read your page with interest since in our local history of Beckenham Kent, one Humphrey Style who died in 1718 mentions Kenning Hall Place as his residence at the time of his death where he was living with a Frances Shippe who appears to be a mistress or common law wife. Humphrey had inherited Langley Place in Beckenham through his family. And possibly Langley is another lost Tudor mansion. The impression I get from this article is that Kenning Hall was much reduced in size etc by 1700. I can’t say whether Humphrey Style was tennant or owner of Kenning from his will which is viewable on ancestry.co.uk but he leaves money and household items to Francis Shippe describing items ‘in and about my now dwelling house or apartment at Kenning Hall Place Norfolk”.

I think it probably was much reduced by that time. Interesting. Thanks for commenting.

Hi Sarah, did you ever manage to transcribe the Howard inventory and did you publish it on the website? I am doing some research on Mary H and would love to check it out it if it is available in a book or online anywhere

Sadly, ‘no’…maybe when I am retired! ?. I’d still love to but I’d need to learn secretary script before tackling the 200 plus pages!

I’ve transcribed a 1622 inventory for another house. Maybe I should give this one a go.

Hi Aly! Maybe if I share the inventory with you (which cost quite a bit to buy fro the NA), you could transcribe it and share it with me? if you are interested, let me know!

I was brought up at Kenninghall, Place farm as it was known then . My FatherJames Wood “Jimmy”” took over the tenancy in 1945/6 having relocated from Westmorland (Cumbria) . Finding the farm in a state of dilapidation he and the staff worked wonders making the farm a profitable mixed farm the same family of men worked for him until his death in 1980. He was very respected in the community of Kenninghall and district.

What great memories! I wish the people who owned it now were more interested in history and welcoming to those of us who would love to see what’s left – even from the outside!

“The remains of Kenninghall Palace see image below” features in this article but i have not been able to find it. Would be very interested to see it please.

Hi Elly, I have updated the blog and inserted the only picture I know that is out there of what remains of the palace. It is far from perfect but the owners are very private and I understand hostile to people interested in exploring its past. Hence the paucity of images available.

Please can anyone confirm that the Steward of The Fourth Duke of Norfolk, who was executed on Tower Hill in 1572, was called Robert Brown and that he too was executed for carrying out his master’s wishes, presumably carrying messages connected with the Ridolfi Plot.

Was the Steward hanged at Tyburn or Norwich?

I am afraid I can’t help with that. Have you tried contacting Nicola Clark – historian and author who has a special interest in the Howard family?