Suffolk Place: Tudor Southwark’s Des-Res

Sometimes I get ridiculously fixated on knowing more about a lost Tudor building; it gets under my skin and won’t leave me alone until I have researched and written about it. There are a few on my list, including Margaret Beaufort’s ‘Collyweston’; William Cecil’s ‘Theobalds’ and Baynard’s Castle in London. Then there is one more; the subject of today’s blog. It was once one of the grandest houses in London: Suffolk Place in Southwark, built by the ever-charismatic Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk.

Incredibly, Suffolk Place lasted less than 50 years before it was sold and then dismantled. It seems impossible that such a palatial residence was destined to enjoy such a fleeting existence. So, with such a short time span available during which details of the house might have been recorded, I approached this blog with trepidation. What was left to discover? Would I be sorely disappointed, unable to find anything more than crumbs of information that would leave me entirely dissatisfied? Well, let’s dive in and see what secrets Suffolk Place was ready to yield to us curious time-travellers!

Suffolk Place: ‘A Large and Most Sumptuous House’

From the dawn of the Tudor age, right through the sixteenth century, Southwark, situated on the south bank of the Thames, was the point of entry into the City of London for those travelling from the south. Connected to the north bank via Old London Bridge, it was also the starting point for anyone making their way along the old London-Dover road towards the continent. Thus, the sight of the wide thoroughfare through the borough, known as ‘Borough High Street’ would have been familiar to all of the royal court, its ambassadors and visitors from overseas.

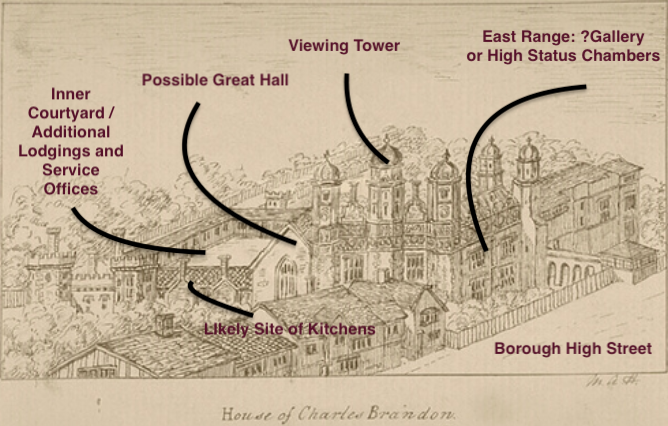

Thankfully for us, the scene of Tudor Southwark has been perfectly preserved through the pen of Antony Van Den Wyngearde in his sketches of London made circa 1543-1550. This particular sketch (see below) captures the great Suffolk Place in all its glory, just a few years before its demolition. So, let us imagine taking a stroll up Borough High Street from the south, and see what we can re-imagine of Brandon’s London home!

Taking a Walk in Tudor Southwark

Transport yourself into the picture above and begin your walk at the bottom of the road. The street here is wide; on your right, pretty orchards give way to two-storey, timber-framed houses, which also run along the west side of the street. Walking northwards, you soon come across a high fence to your left, behind which rises up the grand, eastern facade of Suffolk Place. This towers above the surrounding wattle and daub buildings, which make up much of the Borough of Southwark. Along with the great abbey church of St Mary Overie, which sits at the northernmost end of Borough High Street, adjacent to the south bank, it is by far the most distinctive building in the area. The London Surveyor, John Stow called it ‘a large and most sumptuous house’ and it certainly dominates the High Street.

Standing almost directly opposite the gatehouse of Suffolk Place, on the east side of Borough High Street, is the Church of St George. Unusually, the gatehouse is squat; no towering edifice here, such as that at Hampton Court Palace. The design allows the fine facade of the eastern range, (which probably contained the building’s high-status, privy apartments) to be clearly visible from the road. More on this in a moment. But before we go on and look more closely at the appearance of the house, let’s consider for a moment the origins of Suffolk Place, and the kind of statement that the young Duke of Suffolk was trying to make with his grand, new townhouse.

The Rise and Rise of Charles Brandon

In 1510, the 26-year-old courtier and boon companion of the newly crowned Henry VIII inherited an interest in a place called Brandon House in Southwark, from his uncle, Sir Thomas Brandon. Nobody knows for sure what this house looked like, but a recent archaeological report suggests that it was significantly smaller than the house which would replace it and that it was probably set back from the road and constructed around a single courtyard.

In 1512, Charles was created a Knight of the Garter and, following a successful campaign alongside the king in France, in 1514, he was rewarded by being created Duke of Suffolk – a stunning piece of social climbing! Charles Brandon was now one of the premier aristocrats in the land, a position which was further cemented through his controversial marriage to Mary Tudor, the king’s sister, following the death of her first husband, the King of France, in 1515.

The duke clearly needed a residence to reflect his elevated status and house his expanding family. Although Brandon’s uncle, Thomas, had left the bulk of his Southwark estate to the formidable Lady Jane Guildford (known as ‘Mother Guildford’, governess of Princesses Margaret and Mary Tudor), he soon gained possession of this estate from Jane in return for an annuity of £47 6s. Shortly after, in around 1516, Brandon set about augmenting and beautifying the existing house. Its replacement, now named ‘Suffolk House’ to reflect Brandon’s dukedom, was probably finished sometime circa 1521-2. In June of the latter year, Charles hosted a royal visit; the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, dined at Suffolk Place and afterwards hunted with Brandon in his deer park.

The architect in charge of the works at Suffolk Place is not known. However, what is certain is that Charles had a taste for the latest fashion. His mansion was built of typical, Tudor, red brick, with onion-domed turrets built onto each corner of the house. On its southern facade, there was an additional tower, midway along the range. This was likely used for pleasure; a space of greatly elevated position from which to enjoy fine views of the estate, and the skyline of Tudor London, similar to the function of the Prospect Tower at Oatlands Palace.

The house was decorated by diapering to create patterns in the brickwork, and the eastern facade was covered in terracotta roundels and friezes, (similar to those you can see today at Hampton Court Palace). Figures and patterns evident include ‘the head of a girl, a cupid, the head of a crowned lion, an urn flanked by two griffins, a mythological figure, an urn, [and] a closed crown’ There are also frieze borders decorated with ‘intertwined bay leaf or laurel garlands’. It was the height of renaissance fashion and made for a spectacular display from the roadside!

The Layout of Suffolk Place: A Back-to-Front Town House

From Wyngaerde’s sketch, it seems that Suffolk Place was a double courtyard manor house. Usually, the pattern seen in houses of the day was for the outer court to contain additional lodgings and service buildings, while the inner court was reserved for high status, privy lodgings. Not so at Suffolk Place, where the arrangement appears to have been reversed. Possibly determined by the original position of Brandon House, the Duke of Suffolk may well have bought up tenements fronting onto the road and squeezed in the new residential block, arranged around its own smaller courtyard, between the original courtyard and the road. This courtyard was accessed in its most north-easterly corner via the outer gatehouse and the 4-arched bridge (visible on Wyngaerde’s sketch) that connected it with Borough High Street.

The grand residential block likely included a great hall, upper-storey gallery, household lodgings for guests, family accommodation and a chapel; the latter is specifically mentioned in an inventory of December 1535, when its contents included a large array of liturgical vessels and six gilded images of saints. It seems likely that the gallery or the most high-status lodgings fronted onto the High Street at first-floor level, where the largest of the mullioned windows can be seen on Wyngaerde’s sketch, do doubt flooding the fine chambers within with afternoon sunlight.

Look again at the sketch and notice on the southern facade (facing toward you) a building with an inverted ‘V’ shaped roof and a large arched, mullioned window; it is thought that its position, between inner and outer courtyards, makes this building most likely to have been the Great Hall of Suffolk Place. In a grant made by Mary I in 1556, other buildings mentioned include: ‘barns, stables, dovecotes, gardens, banqueting houses and conduits totalling 14 acres’.

Suffolk Place: A Most Royal Residence

Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, dominated local life in Southwark, far more than he could anywhere else, and the priority accorded to Suffolk Place fitted this fact. According to Suffolk Place, Southwark, London: a Tudor palace and its terracotta architectural decoration by Terence Paul Smith et al., there were many parallels to be drawn between the appearance of Suffolk Place and the Duke and Duchess’ country house of Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk. However, Suffolk Place, ‘which for 20 years Brandon used more than any of his other residences, was the first and most important of these projects; the building work on his other estates was on a much smaller scale’.

To underline its grandeur, it was visited on more than one occasion by royalty. The first recorded visit we have already noted; made by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in June 1522. Charles had recently arrived in England, and on Friday 6 June he had entered the city via London Bridge, alongside Henry VIII, there to be lodged in Blackfriars for 3 nights. Banqueting and masques were held that evening and the one following, before the two monarchs heard high mass at St Paul’s on Whitsunday, followed by Evensong at Westminster Abbey. On Monday, Charles crossed London Bridge once more, this time to dine ‘with the Duke of Suffolk in Southwark, and “hunted there in the parke” and thence departed to the King’s palace at Richmond.’

It would be the last royal visit hosted by Charles Brandon. After Mary Tudor’s death in June 1533, the duke fell into financial difficulty. The ensuing debt settlement was to cost him both Suffolk Place and the newly built Westhorpe Hall. Henry VIII, no doubt attracted by this fine residence with its excellent hunting park, offered to settle part of the debt by exchanging Suffolk House with Norwich House, close to Charing Cross – presumably a less desirable property. And so, in February 1536, Suffolk Place came into the possession of the Crown.

On 1 June of the same year, it was granted to Jane Seymour, following her marriage to the king. There is no record of her visiting as far as I am aware, however, her son, Edward VI dined there on 17 October 1549. It was at an interesting time; Edward Seymour, Lord Protector had been arrested for treason only 6 days previously. According to John Stow ‘to this place came King Edward VI., in the second year of his reign, from Hampton Court, and dined in it. He at that time made John York, one of the sheriffs of London, knight, and then rode through the city to Westminster.’

There was one more brush with royalty before Suffolk Place was torn down; Queen Mary and her husband, Philip of Spain, stayed the night there on 17 August 1554, before making their state entry into London the following day. A letter from John Elder in The Chronicle of Queen Jane and Queen Mary provides us with a little more detail: ‘On Friday, August 17th, the King and the Queen landed at St. Mary Overie’s Stairs on the Southwark side, and every corner and way was lined with people to see them. They passed through Winchester House, my Lord Chancellor Gardiner’s and slept that night at Suffolk Place.’

It was a moment of triumph for Mary, but Suffolk Place’s days were numbered. The queen granted the house to the Archbishopric of York in February 1556 and soon after it was sold on. The house was dismantled by its new owner and ‘many small cottages’ were erected in its place. Quelle horreur!

And so, despite its brief but glittering story, Suffolk Place has left behind enough clues to help us piece together the appearance of this palatial residence. It was a tour de force of Renaissance fashion; a place visited by kings and queens, one that witnessed all of Tudor London pass its doors: royalty, pilgrims, traitors and travellers alike. Although it is gone, thanks to contemporary chroniclers, the brush strokes of Master Wyngaerde, and later archaeological excavations, the house of a courtier who managed to reach the very top of Tudor society – and die in his own bed – can survive both on paper and in our imaginations.

References

For those interested in learning more, by far the most detailed reference I came across when researching Suffolk Place was Suffolk Place, Southwark, London: a Tudor palace and its terracotta architectural decoration, by Terence Paul Smith, Bruce Watson, Claire Martin & David Williams.