Potage à la Reine: The Great Tudor Bake Off

There are so many aspects of Tudor history that we can only read about and imagine. Visiting places allows us to connect physically with places visited by our Tudor forefathers. Another way to get close to experiencing the life of a Tudor is through sampling the kind of food that they ate. This blog post is the first of a regular monthly slot in which we explore the many strange and varied recipes that have been written down from the period. In today’s post, we finish our Mary, Queen of Scots month by exploring one dish said to be associated with the Scottish Queen through folklore: Potage à la Reine – or ‘The Queen’s Soup’.

And so, having followed her flight from Scotland to her imprisonment in England, via the mighty castles of Borthwick, in Scotland, and Bolton, in North Yorkshire, let’s sit down and taste this most hearty of soups, one that is fit for a queen!

Potage à la Reine

Numerous books have been written about the food that Mary’s great uncle, Henry VIII, liked and that his chefs at Hampton Court prepared for him. However, we know surprisingly little about the kind of food that was dished up for the Scottish Queen between her arrival in Scotland and her unfortunate escape to England, in 1568.

Whilst the earliest English cookery books dating back to the medieval ages (Forme of Cury circa 1393, written at the court of Richard II), the earliest (printed) recipe collection/cookery book in Scotland dates from 1736. It was written by Mrs McLintock.

The Cuisine of Mary’s France

Mary spent most of her early years (1548-1561) at the French court, where she would have indulged in the very best that French Renaissance cuisine had to offer. Sixteenth century French cuisine was still very much ‘medieval’ in flavour and was not yet influenced by Italian tastes. At that time, Italy was setting the trend, not just in architecture and what to wear, but also for international culinary tastes. This was surely encouraged by Mary’s Italian mother in law, Catherine de Medici.

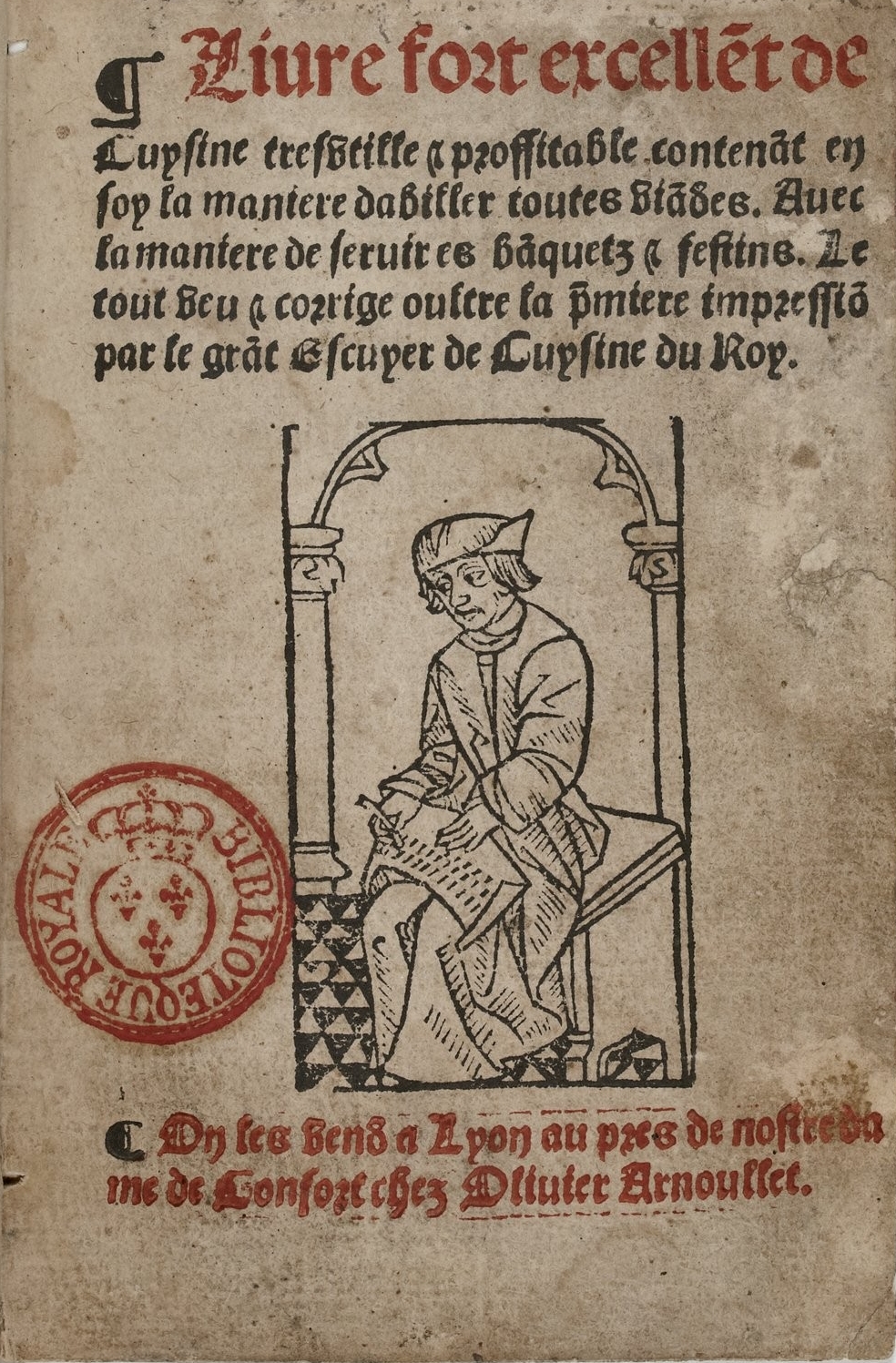

During Mary’s time in France, the new French cookery book Livre fort excellent de Cuysine was published in 1555. Yet its recipes do not differ greatly from previous ones, but rather reflect the emergence of a different culinary style: what we would later call ‘typical’ French cuisine.

The food requirements for the household of the French, royal nursery were enormous. For a single day, 1 December 1551, they included 2 calves, 16 sheep, 5 pigs and 7 geese, as well as choice cuts of beef, chicken, pigeon, hare, pheasant, lark and 36 pounds of cutlets and calves’ feet.

A dish associated with Mary Queen of Scots, and the Chateau of Chenonceau (where she lived during her time at the French court), is dos de sander Marie Stuart (fillet of Pike à la Mary Stuart). The chateau boasted 6 peach-apricot trees, 300 banana trees(!), currant bushes, wild strawberries and 150 white mulberry trees, all growing in its truly spectacular gardens.

Mary and the French court were devoutly Roman Catholic and followed strict ‘fast’ days, going without meat during Lent, Advent and on Fridays, as well as Saturdays. Fruit and vegetables were eaten sparingly during the sixteenth century, both in France and Scotland. Meat was a staple part of the diet.

Those who could afford it, would add dried fruit dishes for flavour and sugar was sprinkled as a spice in both savoury and sweet concoctions. Little cakes, pastries and tarts, as well as sweetmeats, were becoming quite popular. One fruit the Scottish Queen was known to eat until the point of indigestion was melon. Indeed, her tendency to overeat made her uncle, Charles, Cardinal of Guise, anxious. Mary’s indulgence would sometimes cause her to faint; this was alarming, as poisoning was a constant concern at court.

Sugar, as well as spices, was still very much a culinary luxury, and they were an expression of wealth and status. There is no doubt that the young Queen Mary would have favoured sweetmeats or suckets (crystallized fruit), comfits (sugared almonds and seeds) as well as marchpane (marzipan) and ‘marmelade’ – a very thick and sticky paste made originally from quince, and later Seville oranges.

In France, Mary would have been familiar with the sight of orchards in which apples, pears, plums, oranges, lemons and pomegranates were grown; the latter in profusion at the Hotel de Guise, in Paris. At the Chateau de Blois, the relatively rare greengage, introduced from Palestine by Queen Claude – wife of Francis I – grew. They were named after her: ‘Reine Claude’.

In 1538, Queen Mary’s mother, Mary of Guise, complained about missing French varieties of apples and pears. As a result, she had cuttings and trees sent from France to Scotland. It is therefore quite understandable that her daughter, Mary, took a ship-load of French food (dried fruits, cuttings from plum and pear trees) and a hundred cases of French wine with her when she left France for good, in August 1561.

The Cuisine of Mary’s Scotland

When Mary, Queen of Scots landed in Scotland, in August 1561, the stark difference in climate meant a more limited choice of locally and seasonally grown food. This must have made an impact on this young queen, who was used to having such a wide range of fruit available in France.

The basic standard diet in sixteenth century Scotland consisted primarily, as far as can be established with the limited sources we have, of cooked meats, hearty soups, broths, smoked fish dishes, porridge and kale. This simple diet could be supplemented with milk, butter, cheese and fresh fish and meat (mostly salt beef) by those who could afford it. Scottish culinary classics, such as Scotch Broth, Black Pudding, Haggis etc., may have originated during this period.

Wheat was grown in Scotland, but the soil and climate did not favour its cultivation, and in the fourteenth century, the French chronicler, Jean Froissart, noted how Scots soldiers carried bags of oatmeal to make their own oatcakes as a substitute to bread.

In the sixteenth century, Mary Queen of Scots’ arrival in Scotland introduced a touch of French culinary taste to the rather bland diet. This included new methods of food preparation, and the addition of rich sauces, to the traditional, simple, Scottish cuisine.

Folklore associates a number of dishes such as Feather Fowlie Soup, Cock-a-Leekie and Soup à la Reine (Queen’s soup) with the sixteenth century, French-influenced, Scottish cuisine. It is said that Feather Fowlie Soup was one of Mary, Queen of Scots’ favourite dishes. Scottish archives have a paucity of information for anyone researching which food was prepared for Mary, but it seems that while staying at Falkland Palace in Fife, Mary certainly ordered French food and wine.

So, faced with this lack of an original sixteenth century, Scottish cookery book, recipes or manuscripts, I have opted to re-create one of these ‘traditional’ recipes linked to Mary Queen of Scots by folklore, as it will give us a taste of that unique blend of French and Scottish flavour – and should be easy enough for the modern cook to re-create.

Potage à la Reine (The Queen’s Soup): The Recipe

The main ingredient of this dish is partridge. Although, if you cannot get hold of partridge, you may substitute it with capon (a fat, male chicken). Be aware that this will slightly alter the taste of the dish, as partridge brings with it a distinctive taste of game. It is, in essence, the use of game, pistachios and the time taken to prepare the dish that elevates it to its high status. However, if you cannot get hold of a partridge or two down at your local butcher’s, then capon will certainly suffice.

NB: Partridges are related to pheasants, and were only available to the nobility. Pistachios, pomegranate seeds and almonds all had to be imported from Southern Europe, which made them very expensive. The original recipe asks for ‘cockscombs’; literally the comb of a cock’s head; possibly, this was used to symbolise a crown. However, we have chosen to omit this particular ingredient in this modern adaptation to mitigate potential health and food risk.

Serves 4 people

Main ingredients:

2 partridges (available from the butcher)

3 tablespoons melted butter

4 slices salted pork (cured bacon)

1 ½ litre (6 cups/3 pints) water

Pepper

Later – for serving :

4 slices of stale pain de champagne

2 tablespoons pomegranate seeds & pistachios

Partridge stock ingredients:

3 cups meat stock

deboned carcasses of 2 roasted partridges

250g (3 1/2 cups) white mushrooms – chopped

2 cloves

Almond stock ingredients:

3 cups meat stock

Bouquet garni (parsley, chives, thyme)

¼ lemon (just the pulp – no peel)

150g ground almonds

Crumbs of 2 slices white bread

Salt to taste

Potage à la Reine: Advanced Preparation

1. Roast the partridges. Sprinkle them with pepper, put them in a roasting tin – breast side up. Baste the birds with the melted butter, cover them with slices of salt pork. Roast them for 50 minutes in a pre-heated oven (175 degrees C / 350 degrees F ) and baste regularly.

2. Remove the salt pork slices ten minutes before the end of the roasting time. When done, remove the partridges from the oven and leave them for 15 minutes before de-boning. Keep meat and bones apart.

3. Now, make the partridge stock with partridge carcasses, chopped mushrooms and cloves and bring to the boil in the meat stock. Cover with a lid, and simmer for 60 minutes. Then strain through a fine cloth.

4. Meanwhile, make the almond stock while the partridge stock is simmering. Put the almond stock ingredients in a pan and bring to the boil. Let simmer for twenty minutes. Stir frequently to prevent burning. Then strain through a fine cloth, squeezing the pulp to get as much liquid as possible.

5. Method:

In Le Cuisinier Francoise, the potage is finished in ‘the pot’.

The two stocks are not stirred together but added separately on serving. If you prepare it like this, take care that every plate or bowl gets something from element (bread, meat, both stocks and garnish ). It is easier to assemble the potage in individual plates or bowls, provided they are ovenproof. Start by preheating the grill.

Chop the partridge meat very thinly. Take preheated soup plates or bowls and put a slice of bread in each of them. Pour the warmed meat/partridge stock over the bread and then some of the almond stock. Place the plates/bowls under the grill for 5 minutes. Just before serving, sprinkle the pomegranate seeds on top and serve hot.

Original Recipe (English translation)

‘Take Almonds, beat them, and boile them with good broth, a bundle of herbs, and a peece of the inside of a lemon, of crumbs of bread a little. Then season them with salt, have a care they burn not, stir them very often & strain them. Then take your bread & stove or soak it with your best broth, which you shall make thus. When you have taken the bones out of some rosted partridge or capon, take the bones and beat them well in a mortar.

Then take some good broth, seeth all those bones with some mushrooms, & strain all through a linen cloth, and with this broth stove or soak your bread, and as it doth stove, besprinkle it with broth of almonds and with juice. Then put into it a little of some very small hash, be it out partridge or of capon, and alwayes as it doth stove, put in it some almond broth untill it be full. Then take the fire-shovell red hot, and pass it over it. Garnish your potage with cock’s combes, pistaches, granates and juice, then serve.’

During her years in English captivity, Mary found comfort from eating and started to put on weight. She also sent sugared almonds and marzipan as well as sweetmeats to Elizabeth, in the hope of winning her over.

In her will, Mary left all her confitures, succates, preserves, conserves to her apothecary, a sure sign, that those treats were not just considered worthy of inclusion in a will, but also how much they meant to her. Expensive food in the sixteenth century meant status, wealth and respect. Perhaps we are rediscovering the delights of quality food as homemade cakes, jams, biscuits, and even hampers are once again in demand!

Each week, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens, and researching Tudor furniture.

Sources:

- Rival Queens, by Kate Williams

- Mary Queen of Scots, by Susan Watkins

- * Mary Queen of Scots, by Rosalind K. Marshall

- * Livre fort excellent de Cuysine – English Trans. by Tim J. Tomasik & Ken Albala

- The French Cook, by Francoise Pierre, LA VARENNE, 1653

- Johnna Holloway ( Johnna@sitka.engin.umich.edu)

- Coquinaria ( https://coquinaria.nl/en/potage-a-la-reine/

- A Kindly Place?: Living in Sixteenth Century Scotland, by Margaret H.B. Sanderson

I really enjoyed reading this. It brings a whole new dimension to history to know about the foods and recipes of the time.

Thanks Annina, I really appreciate your support of this blog. Anyway, many more interesting recipes to come I hope!