St George’s Chapel, The Burial of Elizabeth II, Plus More Tales from Inside the Royal Vaults

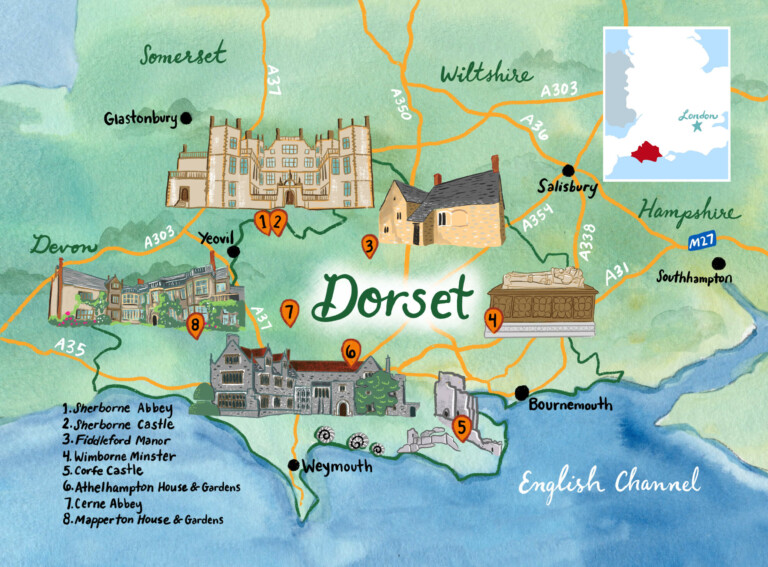

On Monday 19 September 2022, the body of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II was interred in St George’s Chapel, part of Windsor Castle in Berkshire. A few years ago, I wrote a blog about the interment of Henry VIII, whose coffin lies in a small vault under the choir of St George’s. You can read more about the glorious tomb of Henry VIII that never was here. But the place in which the late Queen’s body now lies alongside that of her parents, sister and beloved husband, goes well beyond the story of just that vault. The Chapel of St George has a history that stretches back to the time of Henry I, who ruled England between 1100-1135.

I was curious to uncover more of the ancient secrets of St George’s. And, maybe unsurprisingly, it turns out to have a fascinating history. It is one that is enmeshed with the story of the English monarchy across the centuries; a place for the repository of fabulous bejewelled gifts from the most powerful and wealthy nobles in the land, some of whose bones now lie beneath its floor.

Aside from Henry VIII, one of the most notorious monarchs in English history, several other royal bodies lie entombed there, including those of a decapitated King, (the first and only English King executed by his subjects); a King whose body was exhumed in the 1789 and whose remains are now scattered through the land – (thanks to relic hunters), and a young and beautiful Princess (and heir to the throne) who tragically died in childbirth.

In this blog, I want to bring you some of the most curious and interesting tales from inside the vault, as well as describe where the latest royal coffin will be interred.

St George’s Chapel – An Ancient Order by Royal Command

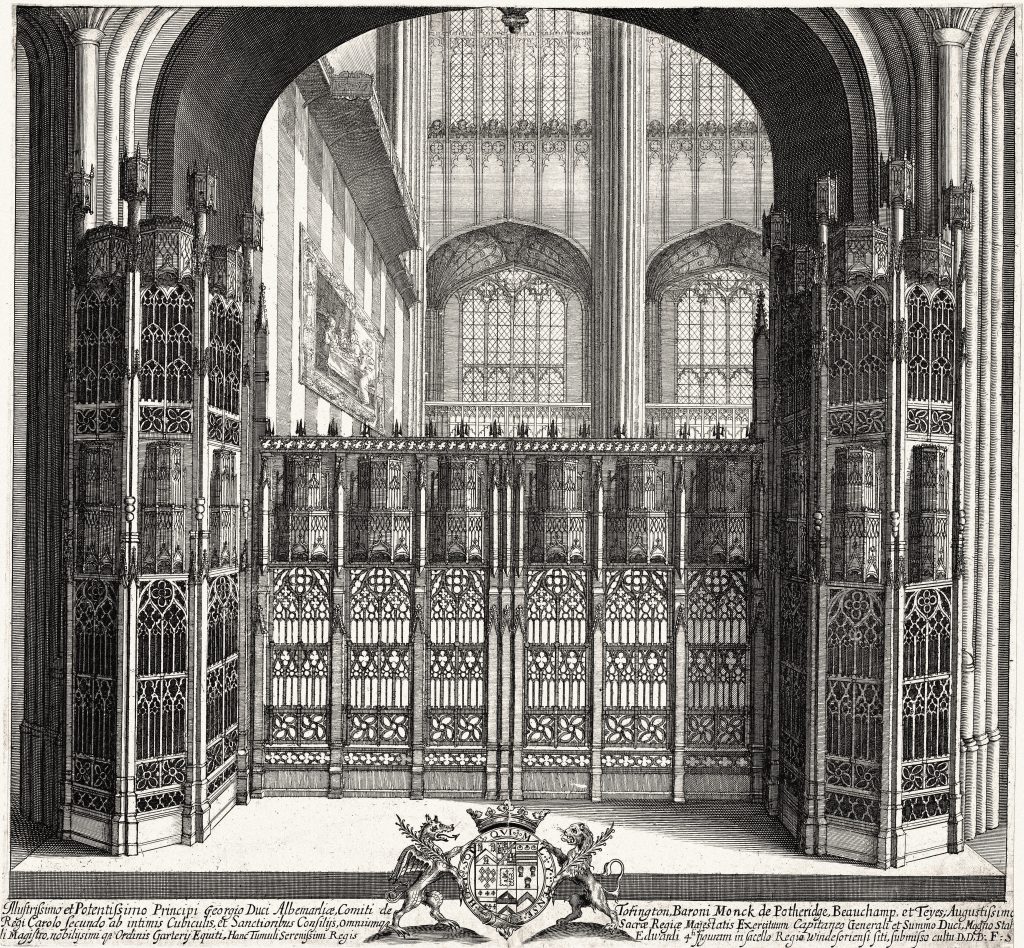

St George’s Chapel is a Royal Peculiar, which means that it is not bound to the parish in which it lies but is under the direct authority of the monarch. This legacy stretches back to the foundation of a free chapel at Windsor by Henry I. However, it was in 1330 that King Edward III moved this foundation from Windsor Park into the castle, so that the King’s chaplains could ‘attend to the divine offices of his soul’.

Then, eighteen years later, the same King formally established a charter of foundation to create an endowed chapel within the confines of the castle walls, established ‘in honour of the omnipotent God, the glorious Virgin His Mother, St. George the Martyr, and St. Edward the Confessor’; St George, of course, being the Patron Saint of England.

Royal Burials: The Macabre Exhumation of Edward IV

We can then jump forward some 150 years to the reign of Edward IV, who set about making extensive repairs and renovations to Windsor Castle, one of his favourite residences. By this time, the castle was nearly 500 years old and probably in need of renovation. Having found the ‘noble collegiate chapel of Edward III to be in an unsafe condition’, Edward IV ordered the chapel’s reconstruction on a more magnificent scale. Here we will pause. The burial, or should I say the ‘exhumation’, of Edward IV’s body in 1789, is the first story from within the vaults at St George’s that I would like to linger over…it is macabre, as these stories tend to be!

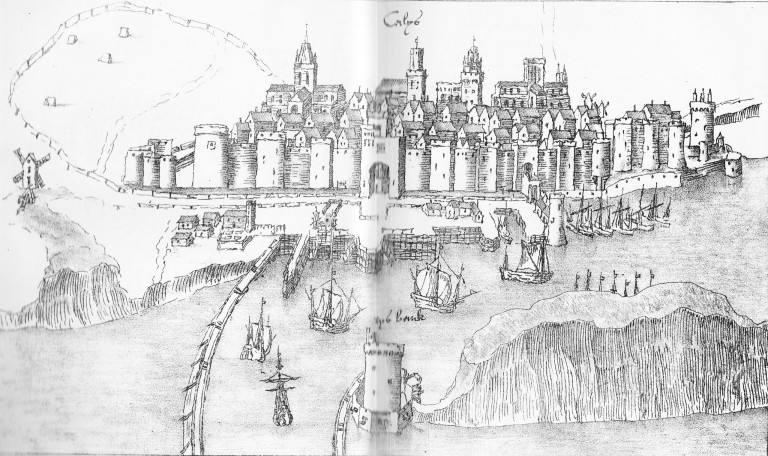

In 1483, Edward died unexpectedly in the Old Palace of Westminster (where, BTW, our late Queen’s body has been lying in state). Being fond of Windsor, Edward’s Will stated that he wished to be buried ‘in the church of the Collage of Saint George within owre [our] Castell of Wyndesour [Windsor], by us begoune [begun] of newe to bee buylded [builded].’

According to British History Online, Edward IV ‘was to be buried in a vault with a chapel or closet over it with space for an altar, and a tomb with his figure of silver and gilt; or at least of copper and gilt. The Will further provided for a chantry of two priests, and for a company of thirteen poor bedesmen to live within the college’. This was so done and the chantry chapel lies, as Edward directed, to the north of the chancel, near the high altar. In case you are wondering, the silver-gilt effigy of Edward IV was never created.

The King’s bones lay undisturbed for 300 years until renovation work was undertaken on the chantry chapel. This was conducted as part of wider work commissioned to repair and remodel certain parts of St George’s on the order of the then monarch, King George III. The King’s carpenter was to design a new stone screen for the chantry chapel, which was to be embellished with medallions and Edward’s coat of arms, as well as lay a new, black marble touchstone upon the floor, marking the site of Edward’s burial, (and that of his wife, Elizabeth Woodville).

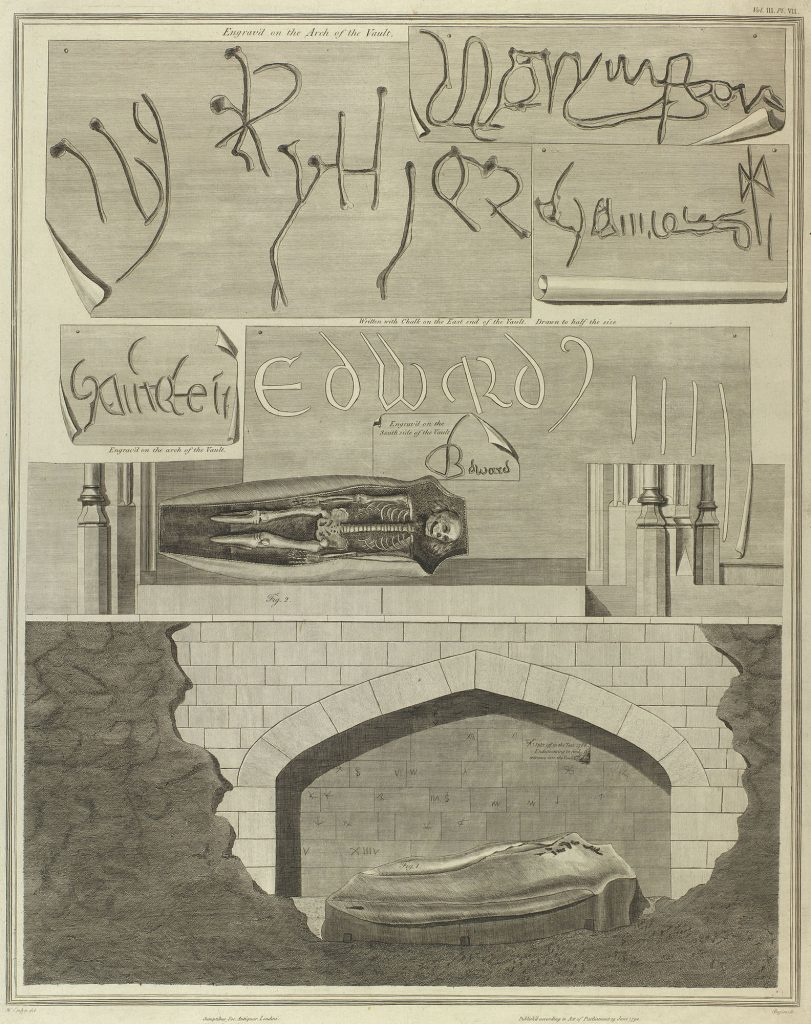

In conducting the work, the paving stones in the north aisle were to be re-laid, since it had been noted that the pavement ‘on one part was sunk’. While undertaking this work, on Friday 13 March 1789, workmen accidentally came upon the burial vault of the long-dead King and his consort. Incidentally, there had been a search for this vault prior to its accidental discovery – but with no luck in identifying either the vault or its entrance.

Anyway, once discovered, the royal burial place was soon uncovered in its entirety. The vault was small; its dimensions were recorded as 9ft long, 4ft 7 inches wide, the arches 2ft 3 inches high with the whole vault buried to a depth of 6ft 6 inches. The words ‘Edwardus iiii’ were found written on the east end of the vault, ‘Edward’ on the south, and possibly ‘Edwarde’ on the arch of the vault.

Within the vault, the remains of a wooden coffin (clearly disintegrated), a skull and bones (of Elizabeth Woodville) lay on top of a lead coffin. Elizabeth had died virtually penniless in Bermondsey Abbey in 1492. Despite her daughter sitting on the throne as Queen Consort to Henry VII, Elizabeth’s funeral was modest. Her wooden coffin attests to that.

The lead coffin, on the other hand, was intact. Curiously, it had been resting at a slight angle, with the head elevated above the feet. In order to get a better look, the coffin was removed from the vault and placed on the pavement for inspection. Quite a crowd, including several of the ‘great and the good’ associated with the royal household or chapel seems to have gathered to witness the opening of the coffin.

They set about opening up the coffin.

What they found was a complete skeleton. On account of the angle that the coffin had been resting in, the lower part of the leg bones and feet were submerged in three inches of a black liquid – later identified, or at least deduced to be, the result of putrefaction of the body, combined with the remains of the wooden coffin. Amazingly, though, Edward IV’s body was in an excellent state of preservation – at least initially!

A newspaper, The Daily Advertizer, noted the following day that: ‘the Body of the monarch appeared entire, the Lineaments of his face were distinguished…’ Material, described as ‘lace’, enshrouded the body, although contemporary records of the King’s burial indicate that the body was actually wrapped in velvet. Linen would also certainly have enshrouded the body as the first layer; it was used ubiquitously for burying the dead of any status during the medieval and Tudor period.

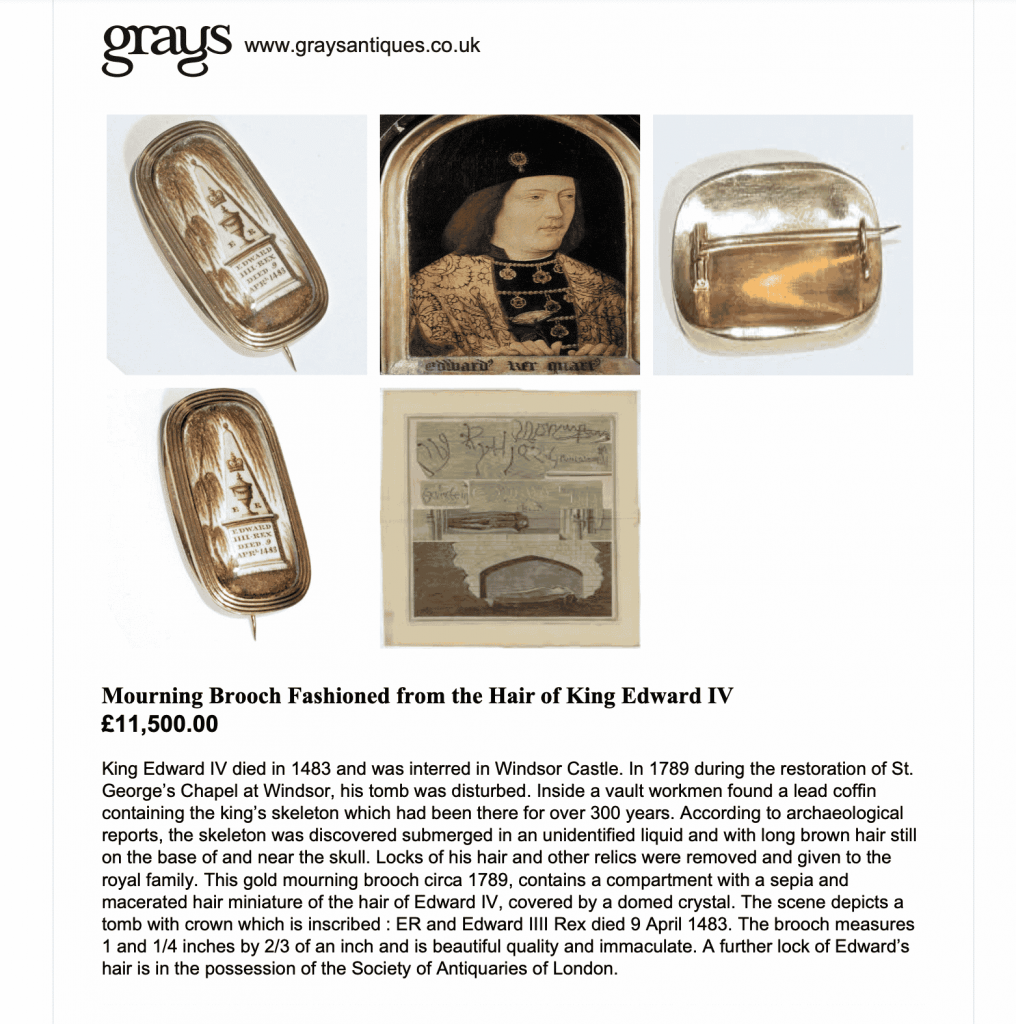

The King’s skeleton was measured and found to be 6ft 3.5 inches. Shoulder-length, brown hair was evident, with shorter strands of hair lying on the neck bones and about the shoulders. This was thought to have been the remnants of a beard. Sadly, though, exposure of the body to the air caused the corpse to disintegrate almost instantaneously. As one eyewitness account stated: ‘When the coffin was opened the body bore its natural form but soon fell to powder’. This is an all-too-well-known phenomenon. The effect of air coming into contact with a previously well-preserved body is well documented, as we can also see in the case of the opening of the coffin of Katherine Parr at Sudeley Castle

As with Katherine’s exhumation, academics and relic hunters could not resist the urge to steal away a piece of the body. Many strands of hair were taken from the coffin or cut off from the skull. Other relics that were stolen are mentioned in a contemporary account called, ‘Guide to Windsor‘. They included teeth and fingers…a leg bone was also said to have latterly been removed and sold at auction! According to ‘The Royal Funerals of the House of York at Windsor‘ (to which I am much indebted in writing this blog) 12 or 13 strands of Edward’s hair are known to have survived and can still be traced today.

It certainly goes to show that royal status does not confer upon a person the utopia of everlasting peace upon this earth! Now, we shall leave this intriguing tale behind and turn our attention to another royal vault that lies beneath the floor of St George’s Chapel.

The Accidental Discovery of an Executed Monarch

It is always amusing to me how the exact position of royal vaults and the bodies they contain is not always meticulously recorded at the time of burial. So, it is not unheard of for royal bodies to be ‘lost’ and their rediscovery is often accidental. I have seen it before with the vault containing the remains of James I of England in Westminster Abbey, for example, and we have just witnessed the very same in the case of the vault containing the corpses of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Now, unbelievably, in the very same building, this second tale tells a similar story…

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the then-monarch, George III, spent huge sums of money refurbishing Windsor Castle. St George’s Chapel was also extensively renovated. One of the items on the royal agenda was to build a new mausoleum in the chapel as Westminster Abbey was ‘full’. The new ‘Tomb House’ (as it was known) was to be constructed directly underneath the chancel of St George’s Chapel. During the course of creating a passage to it underneath the choir, workmen accidentally came across the wall of a missing vault, believed to be that of King Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour.

On Thursday 1st April 1813, the vault was entered in the presence of the Prince Regent. The party were keen to ascertain the identity of the body contained within a third, adult-sized coffin. Whether those present suspected that this was the body of the executed King Charles I at the outset is not quite clear from the contemporary account. However, this does seem to be the focus of their curiosity.

It was long known that Charles’s body, which was known to have been buried in St George’s Chapel, was missing. No clear account of its exact final resting place remained, merely a description of the burial from Mr Herbert, a Groom of the King’s Bedchamber. He was a faithful servant of the King, who had been entrusted with the burial of Charles’ body.

The vault was measured at 7 ft 2 inches in width, 9 ft 6 inches in length and 4 ft 10 inches in height. The coffin was covered with a velvet pall, fitting the description left by Mr Herbert. Underneath the pall, was a plain leaden coffin, bearing the inscription ‘King Charles I – 1648’. One would have thought that would suffice as clear identification of its occupant, but not so!

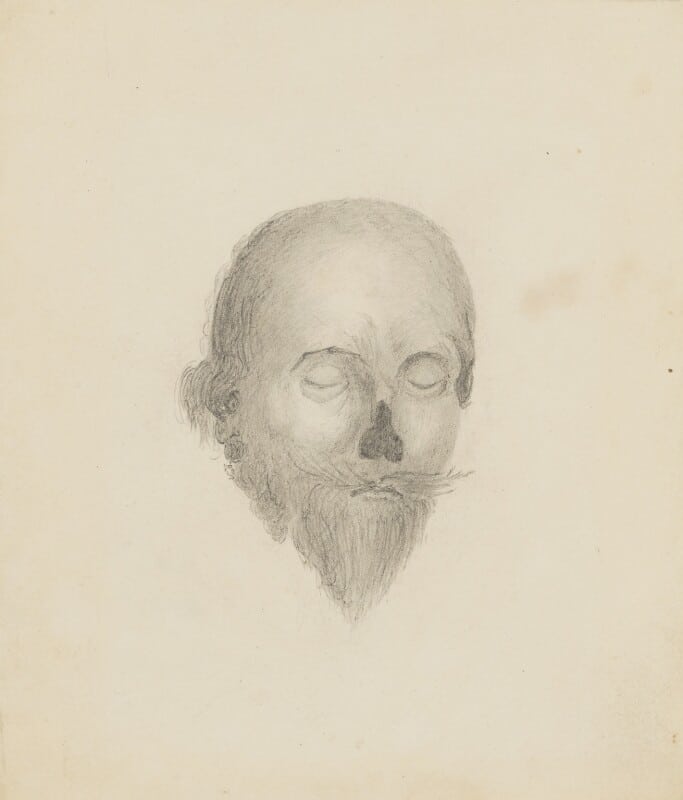

The coffin was duly opened at the head end. There were accounts contemporaneous with Charles’ execution that the King’s body was immediately embalmed after death. Our intrepid explorers note that the cere-cloth used during such a process was wrapped around the corpse and was steeped in ‘unctuous’ or ‘greasy’ matter and resin, clearly meant to keep the air out and preserve the body.

Once the cere-cloth had been carefully removed from the face, the King’s visage was revealed. The skin was ‘dark and discoloured’; the forehead and temples had ‘lost nothing of their muscular appearance’; although the cartilage of the nose was gone, the left eye was, for a fleeting moment, seen as open and perfectly preserved before immediately crumbling into dust – as we saw with the body of Edward IV. Charles’s hair seems to have been well preserved and was dark brown. His face was ‘long and oval’ and sported a ‘pointed beard, so characteristic of the period of the reign’.

© National Portrait Gallery, London via http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Rather gruesomely, the head was then removed from the body. Much stickiness was noted between the head and its neck and was attributed to dried blood, thought to have continued to ooze from the King’s main blood vessels for some time after the embalming process was complete. However, with a bit of manoeuvring, Charles’ head was lifted and examined. It was noted to be cleanly severed from the shoulders at the level of the fourth cervical vertebrae. Finally, the party concluded that this could be none other but the lost King, Charles I: the only English monarch to be executed by the people in the struggle between the Crown and Parliament, a struggle which ended with the King’s death in 1648.

While they were there, the second coffin, thought to contain the body of Henry VIII, was inspected and found to be broken (possibly when Charles’ coffin was unceremoniously dumped into the vault) and the body inside was reduced to a mere skeleton. Short hairs were also found, thought to be part of the King’s beard. It seems that nothing was removed – and if it was, no one was admitting to it! Finally, the coffin belonging to Jane Seymour was noted to be entire and the decision was made not to break it open out of mere curiosity.

Although the contemporary account does not note it, I assume the vault was resealed.

The Royal Tomb House, St George’s Chapel: Is this Where Elizabeth II Will Be Buried?

As I mentioned above, in the early nineteenth century, George III created a new royal mausoleum within St George’s Chapel. This became known as the ‘Tomb House’.

As the image below shows, the Tomb House consists of a series of shelves, upon which currently rest 25 bodies of royal descent. The first of these was placed in the vault in 1810, soon after its construction was complete.

In 1817, the body of Princess Charlotte was also buried in the vault. She died just hours after a traumatic labour (her infant son was stillborn). Nobody knows why she died, as Charlotte appeared to have survived the birth, although it is now speculated that a pulmonary embolism was the cause of her sudden demise.

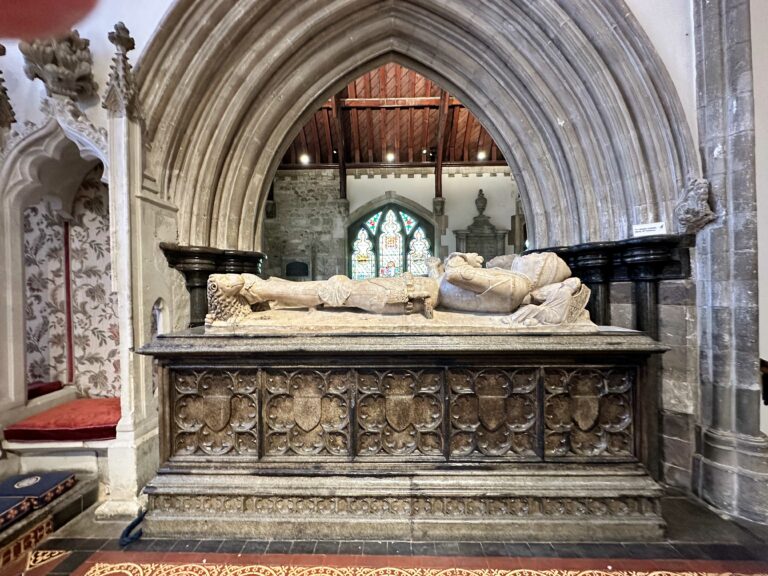

Her obstetrician subsequently committed suicide, no doubt under grievous pressure he felt at ‘failing’ his patient. Charlotte’s death was a tragedy for the nation. She was much-loved and deeply grieved. Interestingly, as the only surviving child of George IV, Charlotte’s death, and that of her child would eventually result in the unexpected accession of Queen Victoria. If you visit St George’s Chapel today, you can see a moving monument to the 21-year-old Princess in the northwest corner of the chapel.

The last two members of the royal family to be buried in the Tomb House are the Duke of Edinburgh, who died in 2021, and Queen Elizabeth II. They have been buried in the George VI chapel on the north side of St George’s Chapel. In doing so, the Queen lies reunited with her family, including the Queen’s father, George VI, her mother, Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother, and her sister, Princess Margaret.

In the death of Elizabeth II, we see the end of an era in which we have undoubtedly lost a fine human being and an example to us all. However, can I make a plea to the record keeper at St George’s? Do make an accurate note of where she is buried!

Sources

Sutton, A F and Visser-Fuchs, L 2005. The Royal Funerals of the House of York at Windsor, London

A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 2. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1907.

Halford, Henry, Sir, Bart., 1766-1844. Essays And Orations, Read And Delivered At the Royal College of Physicians: to Which Is Added an Account of the Opening of the Tomb of King Charles I. 2d ed. London: J. Murray, 1833.

Royal vault: Inside the burial chamber that houses 25 royals – Who is buried there? The Independent

Charles I was executed in January 1649!

Well, actually, at the time, he was executed in 1648. Until the mid 1700s England still started the new year on 25 March – Lady Day, not 1 January as we do today!