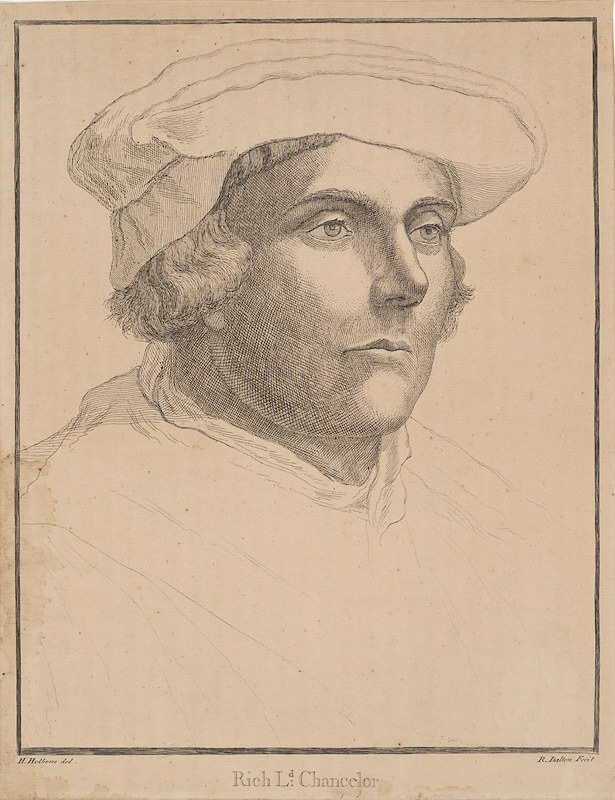

Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich

Name and Title: Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich and Lord Chancellor of England.

Born: Basingstoke, Hampshire, July 1496.

Died: 12 June 1567, Rochford, Essex.

Buried: Holy Cross Church, Felsted, Essex.

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Rich was born in Basingstoke, Hampshire, in 1496. At the time, the Tudor dynasty was in its infancy, and Henry VII was the reigning monarch. Henry VII’s second son, also called Henry, was just five years old, and in time, he would be the first monarch Rich would serve.

Richard Rich was a self-made man; his intellect secured him a place at Cambridge University before he came to London in 1516 to train as a lawyer at Middle Temple.

By 1528, when Rich was 32 years old, he began his stellar climb up the greasy pole of Tudor society. He was ambitious and proactive. Rich had already put himself forward for election to an office in the City of London, although he failed to secure the appointment. Undaunted, he then wrote to the premier statesman in the land at the time, Thomas Wolsey, Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, requesting a position in his household. Although he was not appointed there either, not long after, in December 1528, he secured his first substantive post as Commissioner for the Peace for Essex and Hertfordshire. Here, we see Rich’s connections with the County of Essex being well and truly forged, connections that would remain in place for the rest of his life.

During this period, Rich made friends with the man who would be instrumental in facilitating his future career at the centre of court life: Thomas Audley. Audley was eight years older than Rich, a groom of the chamber and a member of Wolsey’s household. As Audley’s career took off, so did Rich’s, with Audley’s rising star enabling his progression. Through the 1530s, the two pop up side-by-side, repeatedly overseeing the downfall of one unfortunate soul or another.

However, if we are generous to both gentlemen, it would be to consider the nature of their appointed roles as Henry VIII’s ministers of state. Like Rich, Audley was a lawyer trained at Inner Temple in London. On 26 January 1533, the day after Henry VIII’s secret marriage to Anne Boleyn, he succeeded Thomas More as Lord Chancellor. Not long after, probably with Audley’s help, Rich was appointed as Solicitor General, the premier lawyer in the land. Thus, both were in positions of power, overseeing the judicial and legislative functions of the realm. An integral part of the job descriptions of both men would have required them to dispense the King’s ‘justice’. However, my generosity for Rich ends there, for it seems that sometimes he went above and beyond the call of duty in pursuing the ‘truth’.

Images of Richard Rich and his wife, Elizabeth Jenks, as captured by Holbein. c. 1532.

We know that Rich was not only involved in the downfall of Anne Boleyn but also that of Bishop Fisher, Sir Thomas More, Katherine Howard, Anne Askew, Thomas Cromwell and the brothers Edward and Thomas Seymour. He had been one of Cromwell’s proteges but entirely abandoned him in his hour of need and without, it seems, any qualms, happily providing damning testimony against his former friend. As for the 25-year-old Anne Askew, we know Rich personally turned the wheel on the rack that broke Anne’s body.

Torturing a woman at the time was illegal, and the Constable of the Tower, Sir William Kingston, had refused to do so. Nevertheless, this did not prohibit Rich’s pursuit of a confession that, if given, would have implicated Katherine Parr and some of her ladies in charges of heresy. Bravely, and despite her ordeal, if Anne did know anything of Katherine’s possession of heretical, Protestant texts, she refused to yield to Rich’s bullying and torture.

While we might look back at Rich with distaste, if we were to wonder whether our view is being distorted by the lens of time, we only have to read Sir Thomas More’s damning testimony of Rich’s character to know that even in his day, the man was thoroughly disliked by most of his contemporaries. At his trial, More accused Rich of being a perjurer, an idler and a gambler, claiming Rich was ‘…very light of… tongue, a great dicer and gamester, and of no commendable fame’. The French Ambassador, Marillac, described Rich as a ‘wretched creature’.

More recently, eminent historian Hugh Trevor-Roper described him as someone ‘of whom nobody has ever spoken a good word’ and a 2005 poll of historians by the BBC rated Rich one of the “10 Worst Britons” of the last 1000 years. Quite an achievement!

Image © The Tudor Travel Guide

Around one year later, Richard Rich was appointed to a role that would make his previous participation in such dreadful deads look like child’s play. On 19 April 1536, Rich became the Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations. This office placed him as the chief minister overseeing the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and the subsequent dispersal of monastic property. In the same breath that called Rich a ‘wretched creature’, Marillac lays the blame squarely at the door of the new chancellor as ‘the first inventor of the destruction of the abbeys and monasteries [and] the general confiscation of church property’. This bloody schism would result in death and misery for hundreds of people, while men like Rich profited enormously from the spoils.

Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations

Being Chancellor of the Court of Augmentations meant that Rich had the pick of the crop of newly dissolved monastic properties to add to his property portfolio. He snatched up two properties. These became Rich’s principal town and country residences. The first of these, Rich’s new townhouse, lay just outside London’s city walls at the dissolved Priory of St Bartholomew’s in Smithfield. Here, his family occupied the old prior’s lodgings.

Today, the ancient and entirely glorious church of St Bartholomew the Great still stands, although, thanks to Rich, in a greatly reduced state. Nevertheless, part of the north and south transepts, one range of a cloister, the chancel, and the Lady Chapel remain and functioned from the time of the Dissolution as the local parish church. St Bartholomew’s has some of the most glorious early Norman architecture of any church in London and is worth visiting.

Rich’s second new acquisition would become his country seat: Leez’s Priory, near Chelmsford. Leez, or ‘Leighs’, as it was known then, was a small Augustinian priory that was dissolved in 1536. Rich seized the property for himself and subsequently converted it to a stunning red brick, double courtyard manor house, which you can read about in detail here.

Richard Rich Becomes 1st Baron Rich.

The demise of Henry VIII at the end of January 1547 brought forward a new chapter in Rich’s life. At the end of his life, the late King made provision for Rich to be raised to the peerage. This wish was honoured under the new ‘regime’. Thus, serving under the new boy-king Edward VI and Somerset’s protectorship, Richard Rich was created 1st Baron Rich of Leez on 26 February 1547.

The boy from nowhere had ‘arrived’, becoming part of the Tudor nobility.

The following month, he became Lord Chancellor, assisting Edward Seymour with reforms to the church. However, in typical turncoat fashion, with the accession of the Catholic Queen Mary in 1553, Lord Rich easily bent according to the new direction of the prevailing religious wind. On this occasion, he likely carried out his new role with alacrity. Historians believe Lord Rich was likely a Papist at heart. He became an enthusiastic prosecutor of Protestant bishops in his adopted county of Essex; in the space of three years, he sent around 40 condemned heretics to the flames in the name of religion.

The Disconcerting Tomb of Richard Rich

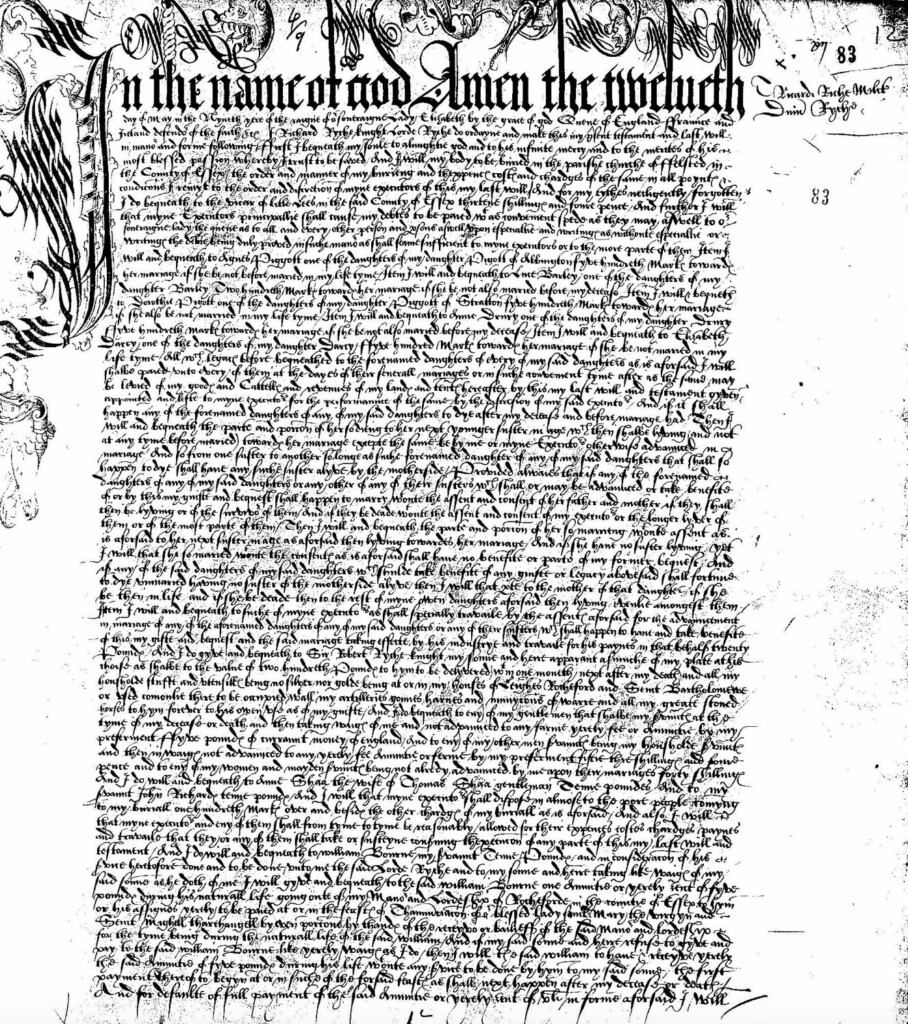

Baron Rich was likely unwell by May 1567, when the first draft of his will was drawn up. A codicil was added on 10 June before he died a natural death in his bed at Rochford, Essex, just two days later; he was 70-71 years old. Subsequently, Rich’s body was conveyed to Felsted, close to his main country manor house at Leez. On 8 July, he was buried in Holy Cross Church, which can be found at the heart of the village. Even today, this is sited adjacent to the school Lord Rich founded as an academic institution ‘primarily reserved for children born on the founder’s manors, instructing them in Latin, Greek, and divinity’.

By the time of his death, Rich had been a widower for around 10 years. His wife, Elizabeth Jenks, Lady Rich, died in 1558 after giving her husband at least 11 legitimate children (I have read that he probably had around four more illegitimate ones). His will decreed that most of his estates went to his eldest surviving son, Robert, including the title of Baron Rich, Robert becoming the 2nd Baron Rich of Leez. His nine married daughters were to ‘share the moveable goods’. At the same time, one of his illegitimate children, Richard, was also provided for on condition that the young man followed his father and namesake in the study of the common law.

However, it took around 40 years for Lord Rich to be endowed with the magnificent tomb we see today. Rich’s grandson, the 3rd Lord Rich, built the south chapel to house the bodies of his father, Robert (who died in 1581), and his grandfather, ‘our’ Lord Rich.

Their impressive, towering, canopied tomb is tucked away in the southeast corner of the chapel. The most eye-catching (and most disconcerting) aspect of the tomb is the reclined effigy of Lord Rich. He is wearing Lord Chancellor’s robes; his right-hand clutches a book; his left elbow rests upon a cushion, while his left-hand props up a weary head. Rich is depicted as an old man with a long, wavy beard; his eyes stare out at you with a lifeless yet eerily penetrating gaze that has lost none of its ability to disquiet the observer.

Above the statue is an inscription panel, but it was never carved. Over this is the coat of arms, with reindeer supporters and the motto Garde Ta Foy (keep thy faith).

Several tableaus are beneath and behind Rich’s effigy. Each one speaks to a different stage of his life and the roles he fulfilled. If you linger awhile to take in the details, they provide a fascinating insight into the Tudor age. For example, the panel showing Rich as Lord Chancellor depicts him carrying the purse containing the Great Seal. In many, mythological Gods and Goddesses accompany Rich, denoting the qualities Rich’s ancestors no doubt wished those who looked upon the tomb to remember him by.

I have taken the following description from British History Online, which describes each tableau in turn…

‘I. The carved panel at the east end of the tomb facing the figure shows Lord Rich as a youth holding a book with two seals in one hand and a long rod or pole with a short crosspiece in the other, and with a dog on his left. By his side stands a female figure with a mirror and a serpent for Truth, one of the cardinal virtues.

II. The carved panel on the spectator’s left denotes his office as Speaker of the House of Commons; carrying a mace and wearing a sword and a short robe. Behind him are two females: the one to the east carrying a column for Fortitude; the other bearing the sword and scales for Justice.

III. The similar panel on the right has, in the centre, his figure as Lord Chancellor displaying the purse of the Great Seal; Hope with anchor on the one hand, Charity carrying one child and holding the hand of another, on the other hand, balance Fortitude and Justice in the other panel.

Beneath, slightly incised on black marble (originally set out in vermilion), are two groups. That on the left shows him arriving at Westminster Hall in state in Lord Chancellor’s robes, mounted on a horse with foot-cloths, attended by the bearer of the Great Seal and other officials. That on the right shows him lying in state, hands clasped in prayer, on a bed under a canopy. A female watcher kneels at each side, a male watcher stands at the head.

Above the monument a winged figure, gilded, with trumpet, represents Fame publishing abroad Lord Rich’s high estate and noble charity.’

Finally, at the west end of the altar tomb is a small reading desk, at which kneels an alabaster effigy in half-plate armour. This is Richard Rich’s son, Robert.

Visitor Information

Like most parish churches, you can visit Holy Cross at most reasonable times of the day. However, to be sure it is open, I would contact the parish office in advance.

Leez Priory is less than three miles away. It is not open to the public and is now a wedding venue. However, with an earnest request, you may be able to wander around and see the remains of Rich’s beautiful country home if no wedding is taking place.

Other Locations Nearby

Paycockes House (13 miles)

Newhall School (Beaulieu Palace) (8 miles)

Ingatestone Hall (17 miles)

Layer Marney Tower (23 miles) and the tomb of Lord Henry Marney

Sources of Interest:

E A Webb, ‘Sir Richard Rich‘, in The Records of St. Bartholomew’s Priory and St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield: Volume 1(Oxford, 1921), British History Online [accessed 27 February 2025].

Richard Rich. Find a Grave.

RICH, Richard (1496/97-1567), of West Smithfield, Mdx., Rochford and Leighs, Essex. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558, ed. S.T. Bindoff, 1982.

‘Felstead‘, in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Essex, Volume 2, Central and South west(London, 1921), British History Online [accessed 27 February 2025].

Brilliant article, Sarah. I always new he was a bad’un! I am back in England in June. I think I might even have St Bartholomew’s on my wishlist for visits. Not spending a lot of time in London, but I might find the time for a look-see. Thanks for all your amazing work. My inventory of places to visit just keeps expanding. Happy days!