Mortlake Manor: Cromwell’s Palatial Residence on the Thames

The subject of today’s blog is a place that I would bet very few Tudor history fans know about. Yet, in its time, it was once a palace and later became a cherished residence of one of the most powerful figures in Tudor history – and a time that would change the very fabric of English society. This building deserves to be in our collective memory, alongside many other great Tudor houses. Therefore, I would like to introduce you to Mortlake Manor in Surrey. It has long since been lost to time, and yet, 500 years ago, it witnessed the pinnacle of one man’s rise to glory and his bloody demise.

But first, let me share with you the story of my compulsion to research this blog…let’s turn back the clock to just a few months ago.

The Man in the Spotlight

In front of me stood a broken man facing imminent death. His creased linen shirt, once so pristine and neatly tied at the base of his throat, hung open, exposing a thick-set neck that the sharpened blade of the axe would soon sever. I held my breath in the eery silence as Thomas Cromwell spoke:

‘I am come hither to die, and not to purge my self, as some think peradventure that I will. For if I should so do, I were a very wretch and a Miser. I am by the Law condemned to die, and thank my Lord God, that hath appointed me this death for mine Offence…’

This man had seen all of life and had shaped the destinies of countless others. Around me, a pin could be heard dropping in the theatre auditorium as this version of Thomas Cromwell faced his brutal end. As the axe fell and the curtain closed on the last act of Hilary Mantel’s Mirror and the Light, I was stung by a sadness that surprised me. For many years, I had neatly boxed up Master Cromwell as nothing short of a pantomime villain. But things have changed recently.

In the last couple of years, I have written two major blogs about properties belonging to Cromwell: Austin Friars in the heart of the City of London and his country house at Stepney. Last year, I also researched the properties belonging to two men of his inner circle: the thoroughly unpalatable Sir Richard Rich and his property at Leez Priory, as well as the deeply loyal Ralph Sadler and his swanky townhouse in Hackney. In doing so, I read more about Cromwell and spoke with his biographers, including Diarmaid MacCulloch and Tracy Borman. Gradually, I developed creeping respect and admiration for a man who was a genius of statecraft.

And so, I feel compelled to keep going in my quest to unearth the details of more of Cromwell’s life in inimitable Tudor Travel Guide fashion by putting the various properties he owned in the spotlight and weaving in their relevance to Cromwell’s story. This has led me to another of Cromwell’s much-beloved properties. It is a place that saw the wedding of his only surviving child, a wedding that brought the newly ennobled minister closer to the throne through matrimonial ties. So, do not tarry any further: Mortlake Manor awaits you!

Mortlake Manor: A Palatial Residence on the Thames

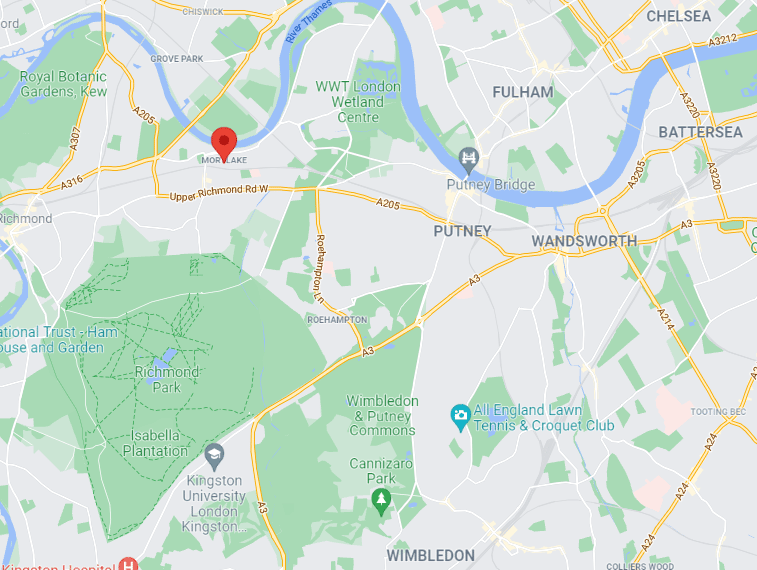

It is little wonder that Mortlake was much sought after by kings and the noblest of English society. If you were to take a river trip up the Thames in the sixteenth century, travelling between the epicentre of English power, Westminster, and the magnificent royal, country residences of Richmond, Hampton Court, or Windsor, you would surely admire Mortlake Manor, lying en route on the south bank of the Thames, halfway between Putney and Richmond.

This palatial property started as one of the archepiscopal palaces of the Archbishops of Canterbury, pre-dating the Norman Conquest of 1066. Three archbishops died at Mortlake, perhaps indicating how much it was valued as a fine country retreat where one might rest and recuperate in the fresh air and away from the filth and pestilence of the city.

Geographically, Mortlake is sandwiched between Putney to the east and Richmond to the west at a bend in the Thames as it meanders its way between the two. The expanse of Richmond Park lies to the south. Its position made Mortlake Manor perfect for the Tudor ‘commute’ on the ‘mainline’ linking Greenwich, Whitehall, Richmond, Hampton Court, and Windsor. At the same time, it afforded a fine pastime in the aforementioned park, where the game for hunting was in abundance.

The importance of this manor house to English royalty can be seen in the number of medieval kings who visited the property, including Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, Edward III, Henry V, Henry VI, and Edward IV. Being so close to Richmond Palace, it is unsurprising that Henry VII is recorded hunting in the park at Mortlake in 1507 (although I have yet to pin down the original reference for myself). I also came across a reference to the newly crowned king stopping off at Mortlake with his new bride, Elizabeth of York, on 18 January 1486 (again, I have yet to find the source for this). The newlyweds were making their way from Westminster, where they were wed by Archbishop Bourchier, to Richmond Palace. Perhaps it is not surprising that they might be the guests of the archbishop on such an auspicious occasion.

1536: The End of the Archbishops’ Palace at Mortlake

1536 was a momentous year for two of the central protagonists in our story: Henry VIII and his first minister, Thomas Cromwell. Through a brutal act of judicial murder, Anne Boleyn and five innocent men died on the scaffold in May of that year. In the thick of it was Cromwell, who had retreated from court during April 1536 to think up and conspire the whole affair. Among the devastation, one of the lone voices raised in speaking for the queen was Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. Cranmer was her reformist archbishop and staunch ally, who wrote gingerly to Henry at the time of Anne’s arrest:

“I am clean amazed, for I had never better opinion of woman”, but then watered this comment down by adding “but I think your Highness would not have gone so far if she had not been culpable…” Diarmaid MacCulloch postulates that it might have been because of Cranmer’s defence of Anne that Henry induced his Archbishop to surrender Mortlake Palace later that summer in exchange for lands elsewhere.

It was clear that the king knew he owed Cromwell a debt of gratitude for ridding him of the ‘goggle-eyed whore’. On 2 July 1536, Cromwell received his first reward, being granted the position of Lord Privy Seal, held by Thomas Boleyn. Then, on 8 July 1536, Thomas Cromwell was elevated to the peerage as 1st Baron Cromwell of Wimbledon. Murder proved lucrative for the new Lord Cromwell. Along with these titles, Thomas was gifted Mortlake Palace, henceforth called Mortlake Manor, along with its adjoining lands. The blacksmith’s son from Putney was returning home some 50 years later as the most influential man in England next to the king himself. Quite an achievement!

Cromwell’s Mortlake

With Mortlake Manor now a part of Thomas’ property portfolio, Henry’s new Lord Privy Seal had the perfect palatial residence, conveniently lying to the west of London. Alongside Stepney in the east and Austin Friars in the City, all the key bases were covered for attending to state business and moving about the various royal palaces sited along the Thames.

Straightaway, Thomas commenced an enormous building campaign at Mortlake, just as he had done at Austin Friars and Stepney. Several references littered throughout Cromwell’s correspondence from around this period pertain to building works at each of his main residences. For example, one written by Richard Tomyow, a servant of Cromwell’s, on 18 August 1536, is dated ‘Mortlake, where Cromwell’s servants are in health and his building ariseth fair’. Clearly, Cromwell had wasted no time in making Mortlake Manor his own!

While we do not know precisely how Cromwell redesigned and furnished his luxurious new home, I was excited to discover shortly after the dramatic end of Cromwell’s life, fortune had smiled kindly upon us and left us with an inventory of the property. This was compiled in 1540 by Robert Throckmorton, ‘servant of Master Trywhit’. It was taken after Cromwell’s execution and when the property had been returned to the Crown by Act of Attainder. The original inventory is currently in the National Archives at Kew, but, helpfully, it was in part transcribed in the 1950/60s by Caroline Crisp.

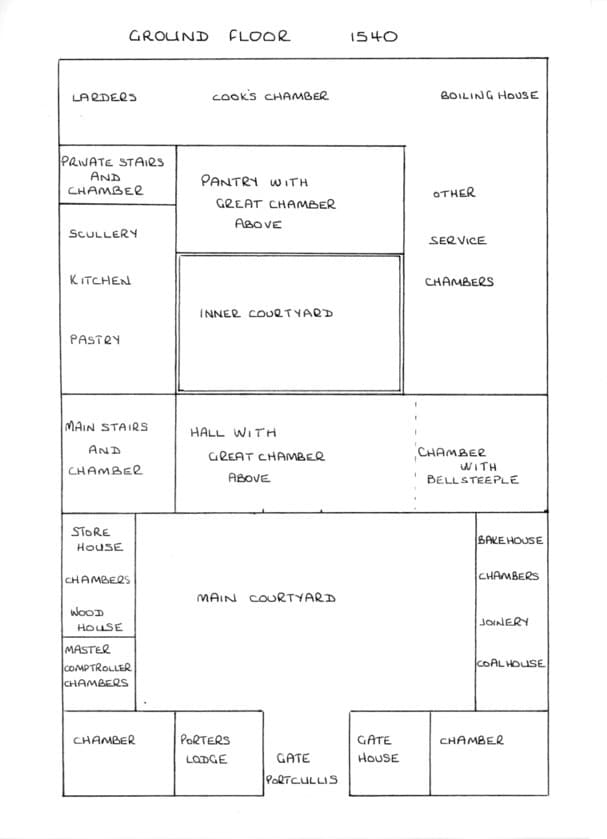

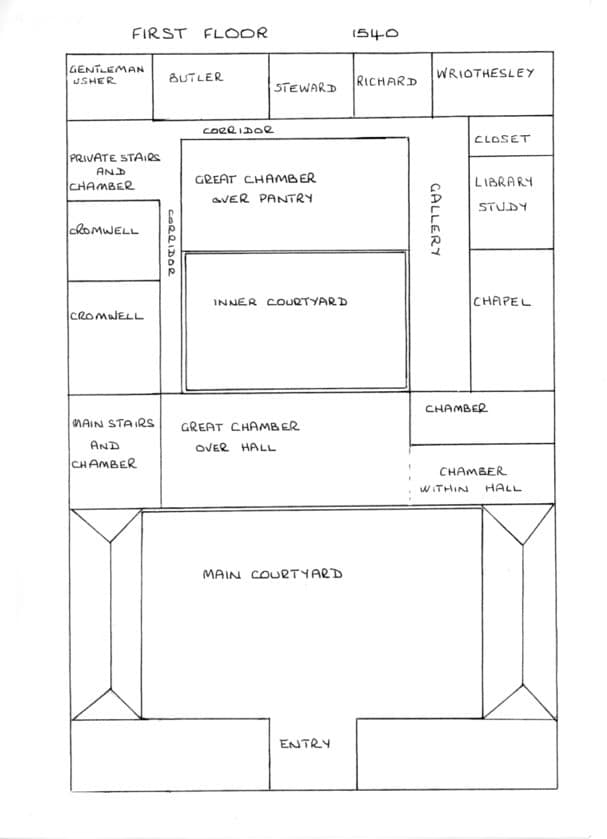

Here, I must pause and say that I am deeply indebted to Helen Deaton from the Barnes and Mortlake History Society. Thanks to the society’s determination to keep local history alive – and Helen’s dedication to uncovering as much as possible about Mortlake Manor – we are able to access this transcribed document. Helen has also translated the contents of the inventory into the manor’s floor plans. (Note: Helen would like me to note that not all the rooms described in the inventory are captured in these diagrams, but the major ones listed are). From all this information, we can reimagine the house that Cromwell knew.

The Appearance and Layout of Mortlake Manor

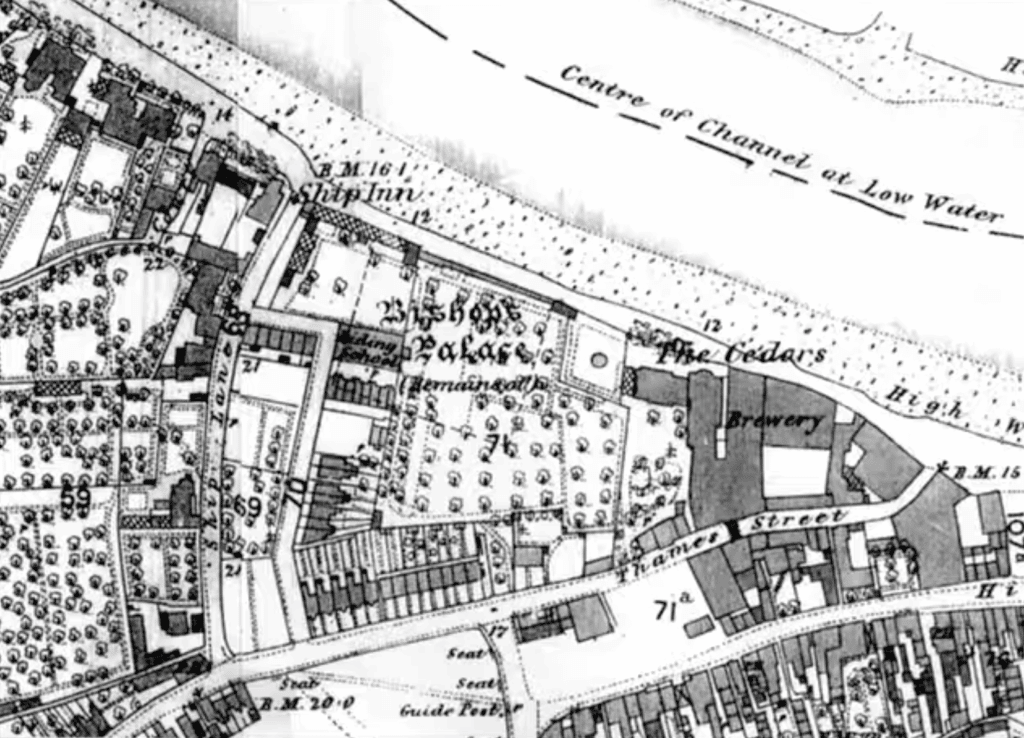

Mortlake Manor was a double courtyard house arranged over two floors. The house covered an area of four acres, its gardens surrounded by a high wall, part of which still stands as the only surviving fragment of the house and gardens. On the north, the property ran parallel to the River Thames, was bounded on the west by Ship Lane, and on the south was Lower Richmond Road and High Street. Like any significant house of the day, a gatehouse gave access to an outer courtyard. Included in this structure was the ubiquitous Porter’s Lodge on the ground floor.

Beyond the gatehouse was the outer courtyard, around which the service buildings or offices of the manor were organised. The inventory lists many of these offices, including the woodhouse, the coal house, the joinery and the storehouse. ‘Chambers’ are also listed, sited above the aforementioned offices. This likely contained accommodation for members of the household or visiting guests.

Directly across the courtyard from the gatehouse was the great hall. This range separated the public space of the manor from the high-status, privy and grand ceremonial chambers that encircled the inner courtyard. Unusually, in the cross-range that contained the great hall adjacent to its low end, we hear of a room with a ‘bellsteeple…with a cord’. So, we can imagine the everyday life of the manor’s residence punctuated by the chime of bells.

Beyond the great hall, the inner courtyard contained the kitchen, pastry, boiling house, larder and scullery on the ground floor and a large pantry sited at the rear of the courtyard, underneath one of Mortlake Manor’s two great chambers. A grand ceremonial staircase led up to the first floor, adjacent to what I presume to be the high-end of the great hall (as it was closest to the end of the house containing Lord Cromwell’s privy chambers). Here, the ‘great chamber over the hall’ could be accessed in one direction; in the other, a corridor led to ‘My Lord’s (Cromwell’s) chamber’ and a separate bedchamber.

The range opposite this contained the chapel, once used by a lineage of archbishops. This was accessed by an adjoining gallery that ran along the length of the range. The inventory notes a mat to be found in the galley measuring 17 yards in length and four-and-a-quarter in breadth, giving us some idea of the gallery’s size. Also, from the inventory, it seems likely that two more rooms were sited off this corridor: a study or library, which is noted to be ‘ceiled [sealed] with wainscot’, and a closet.

At the rear of the house, several rooms are specifically named, including ‘Master Richard’s Chamber’ (Richard Cromwell, one assumes), ‘Master Wriothesley’s Chamber’ and separate rooms used by Cromwell’s ‘Gentleman Usher’, ‘Steward’ and ‘Butler’. Finally, a privy stair, sited to the rear of Cromwell’s privy chambers, likely led down to the private gardens.

Having described the house, I’d like to focus on one of the most notable events to unfold at Mortlake Manor during Cromwell’s four-year affiliation with the property: the wedding of his son, Gregory, in the chapel at Mortlake on a summer’s day in 1537. Another momentous year for the Cromwell family

Three Funerals and a Wedding…

I had already mentioned that in the first 500 years of the manor’s life when Mortlake functioned as an archepiscopal residence, three Archbishops of Canterbury had died at the princely palace. 1537 was the second year of Cromwell’s ownership of the manor, and it would see happier times.

Enter Lady Elizabeth Ughtred.

In March of that year, a letter landed in Cromwell’s inbox. The sender was the eighteen or nineteen-year-old Elizabeth Ughtred, nee Seymour. Elizabeth was the younger sister of the new queen, Jane Seymour. Interestingly, Elizabeth and her first husband, Sir Anthony Ughtred, were loyal to the late queen, Anne Boleyn. His promotion to Governor of Jersey was likely on account of Anne’s intervention. Both Elizabeth and her sister had served in Anne Boleyn’s household. However, with Anne’s execution and Jane’s ascendency, clearly, a discreet withdrawal from the court was necessary for Lady Ughtred.

By this time, Elizabeth’s husband, Sir Anthony, had died (1534), and, as a widow, Elizabeth had settled far away from the scene of her sister’s triumph, taking up residence in Kexby in North Yorkshire. Henry VIII had granted the manor and lands of Kexby to Sir Anthony in 1531. Although Jane’s tenure as Queen of England was brief, Elizabeth would never serve in her sister’s household. The previously divided family loyalties perhaps proved too much of a rift for the new royal household to bear.

However, the Ughtred’s had been friends of Cromwell from way back when the latter had been in the service of Wolsey. In the letter penned by Lady Ughtred from York on 18 March 1537, we can see that Cromwell had previously offered assistance to Elizabeth should she ever need it. Now was the time to call in the favour. Widowed some three years, Elizabeth writes:

‘[to] beg your [Cromwell’s] favour that I may be the King’s farmer of one of those abbeys, if they go down, the names of which I enclose herein. As my late husband ever bore his heart and service to your Lordship next to the King, I am the bolder to sue herein, and will sue to no other. When I was last at Court you promised me your favour. In Master Ughtred’s days I was in a poor house of my own, but since then I have been driven to be a “sojorner,” for my living is not sufficient to entertain my friends. Begs help, as she is a “poor woman alone.” Desires credence for Mr. Darcy. York, 18 March. Signed.’

Instead of providing lands, Elizabeth seems to have been enticed into the marriage market and quickly accepted an offer to become the wife of Lord Cromwell’s only son, Gregory. With Elizabeth’s sister being pregnant with the new heir to the throne and her brother (Edward Seymour) rising rapidly in the king’s favour, Elizabeth’s stock was also up. Securing the lady’s hand would make Gregory the king and queen’s brother-in-law, and effectively, Cromwell would be uncle by marriage to any future king. This was another smart move by Thomas in the chess game of Tudor one-upmanship.

A portrait of a man aged 24, perhaps Gregory Cromwell (c.1520-1551), 1543, Hans Holbein the Younger.

Although only around 12 or 13 years of age at the time of her first marriage, by this time, Elizabeth had matured into a woman of substance with a mind of her own. Within a short time of Thomas’ marriage proposal to his son, Elizabeth moved south from York. She had chosen to lodge with her brother, Sir Edward Seymour, writing graciously, yet assertively, to her future father-in-law:

To the right honorable and my singular good lord, the Lord Privy Seal:

In most humble wise, as your assured poor beadwoman, I cannot render unto your lordship the manifold thanks that I have cause, not only for your great pain taken to devise for my surety and health but also for your liberal token to me, sent by your servant master Worsley; and farther, which doth comfort me most in the world that I find your lordship is contented with me, and that you will be my good lord and father: the which, I trust, never to deserve other but rather to give cause for the continuance of the same. Pleaseth it your lordship, because I would make unto you some direct answer, I have bene so bold to be thus long ere I have written unto you. And where it hath pleased your lordship as well to put me in choice of your own house as others, I most humbly thank you; and to eschew all sayings, I am very loth to change the place where I now am, and where my brother my lord’s house shall remove, the which, if such need e, shall be at one Ambrose Wellose, a quarter of a mile from your lordship’s place, as master Worsely can inform your lordship more plainly thereof. And where it hath pleased your lordship to give me leave, and also commandeth me, if I want, to send to you, and that I may be bold to open my heart, I ensure your lordship my heart hath been a great time in such trust; and now this letter from you, with that I find in it, doth me more pleasure than any earthly good for my trust is now only in you, and if I have any need I shall obey your lordship’s commandment herein. And thus I shall daily pray unto God for the preservation of your lordship most prosperously in health to continue. Amen.

Prayeth your humble daughter-in-law,

Elizabeth Ughtred

(Note this is recorded as being written on 10th October in the Letters & Papers of Henry VIII, but MacCulloch postulates that it might well have been written earlier, before Elizabeth’s marriage to Gregory.)

Thomas Cromwell hurried back from Surrey for the wedding, where the Letters & Papers of Henry VIII show us that he had been on summer progress with the king. The newlyweds were gifted £50 from Lord Cromwell.

The first mention of the Cromwell wedding comes from that inveterate Tudor gossip, John Husee, writing to his master, Lord Lisle, in Calais: ‘My lord Privy Seal’s son and heir shall shortly marry my lady Owtrede, my lord Beauchamp’s sister.’ Indeed, the couple were married in the chapel at Mortlake on 3 August 1537 (again, reported on by John Husee). It was a low-key affair as the plague was raging in London. Diarmaid MacCulloch also postulates that the political sensitivities of an upstart like Cromwell marrying his son ever closer to the throne required some discretion. It would not have gone unnoticed by the nobility of the time, who already resented Cromwell’s power.

The young couple seems to have stayed at Mortlake Manor for at least some of the following months, as their first son was born there. Interestingly, his date of birth is given as ‘before 1 March 1538′, meaning he had been conceived before his parents’ marriage took place. I am not sure of this date’s veracity, so I will pursue the gossip no further! However, we do know that soon after his birth, the couple moved out of their father-in-law’s house to live in another of Thomas Cromwell’s newly acquired properties, the dissolved priory at Lewes, thereafter known as ‘Lord’s Place’.

As for Thomas, things could not have looked rosier in August 1537. Two days after his son’s wedding, he was elected as a new Knight of the Garter. Following a summons to Windsor, where the order was convened, Thomas ‘fell down before the Sovereign, giving with all the eloquence he was master of (and certainly he was master of the best) infinite thanks for the honour conferred upon him.’

However, he could not have known just how events were about to take a tragic turn for the worst. As summer turned to autumn, Jane Seymour would take to her bed, finally to deliver Henry VIII, his son and heir. However, 12 days later, the queen died of puerperal fever. MacCulloch notes how Cromwell returned to Mortlake in the same month, exhausted by the events transpiring at court. The death of the queen would cast a long shadow across London. In some ways, one might see this as the very beginning of the end for Cromwell, for it would draw Henry’s first minister into a quest to find his master a new bride. However, it would take Thomas Cromwell’s enemies a further three years to destroy him on the back of his disastrous orchestration of the king’s marriage to Anne of Cleves.

Mortlake Manor after Cromwell

In April 1540, Henry VIII induced Cromwell to sell the manor and lands of Wimbledon, of which Mortlake was a part. The king was creating an enormous swathe of land called ‘The Honour of Hampton Court’, which connected the palaces of Hampton Court, Oatlands and Nonsuch. Cromwell was undoubtedly gutted to say goodbye to a home he had treasured and was filled with sentimental memories. However, he would not have long to dwell on the loss. At 3 pm on 10 June, Thomas Cromwell, by now 1st Earl of Essex, was arrested at a Privy Council meeting on charges of treason. There was no trial, and he was executed on 28 July 1540, less than a week away from his son’s third wedding anniversary.

British History Online draws from the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII in stating that Henry VIII visited Mortlake on several occasions. He granted the manor to his sixth wife, Katherine Parr, in 1543, with the manor being prepared for her visit in September of that year, when ‘Murtelake [was made] ready against the Queen’s coming.’

After Katherine’s death, during the reign of her stepson, Edward VI, Lord Edward Clinton was permitted to have ‘the brick, stone and tymber and other things at his choice of the dekaied and uncovered house at Mortlake’. According to Helen Deaton, it may well be that some of Mortlake’s interiors found their way to Lord Clinton’s Lincolnshire residence at Tattershall Castle. However, that is now stripped of its decorative interiors. Either way, the manor house was already in a significant state of disrepair, and the removal of material will have only accelerated its decline.

From this point, a long chain of ownership, which increasingly frittered away its prestige, saw the gradual demise of the manor over the next 150 years. According to British History Online, ‘Mortlake House was standing in 1663 but appears to have been pulled down soon after 1700’.

The foundations of the old manor now lie beneath a brewery, shortly due for conversion into residential dwellings. The process requires an obligatory archaeological dig before the new foundations are laid. Until now, other than the definitive location of the gatehouse, no trace of the position or size of the house has been found. It just may be that this latest twist of fate will finally reveal a glimpse of its hidden past. Let’s hope that in the near future, Cromwell’s once palatial mansion on the Thames’ banks will rise again – and this time, more vividly in our imagination than ever!

Visiting Today: If you visit the site today, you can retrace the perimeter of the manor complex. However, the only trace of the remaining old building is part of the precinct wall and a gazebo, which overlooked the river. Also, make sure you visit the nearby church. Originally, a church stood next to the manor. However, Henry VIII had it moved in 1543.

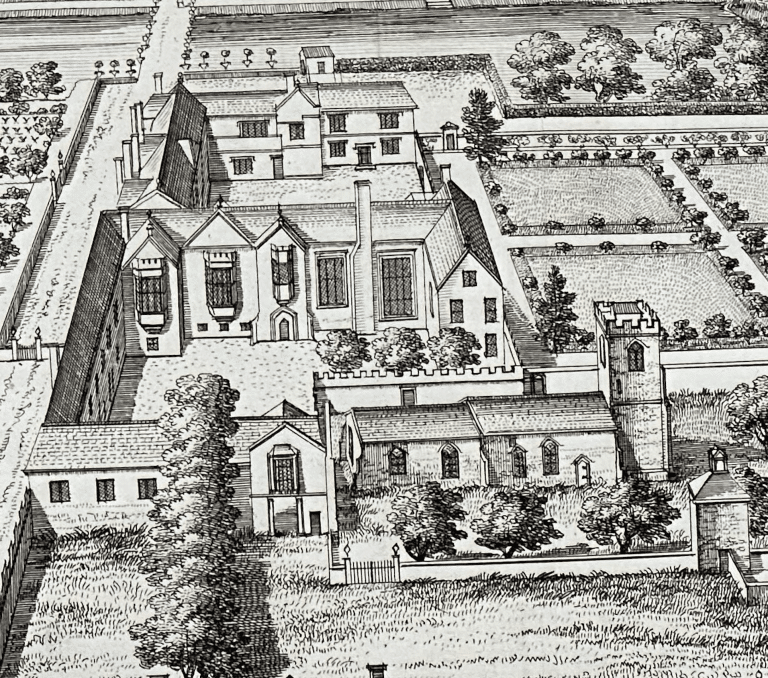

While visiting this site alone might only be for the Tudor connoisseur, Richmond Park, the gatehouse of the original palace, and nearby Fulham Palace are within easy reach. The latter was a residence of the Bishops of London, and it lay further east, downstream along the Thames. Although the palace has been redeveloped over the years, significant Tudor buildings remain on site. These are thought to architecturally reflect how Mortlake Manor might originally have appeared.

Sources

Thomas Cromwell: A Life, by Diarmaid MacCulloch, on Amazon UK or Amazon US

A History of the County of Surrey: Volume 4. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1912.

Mortlake and its Manor House, by The Barnes and Mortlake History Society

Mortlake’s Magnificent Manor House on YouTube by Mortlake History

The History of the Parish of Mortlake by J.E. Anderson. Laurie, 1886

Gregory Cromwell: Two Portrait Miniatures by Hans Holbein the Younger, by TERI FITZGERALD and DIARMAID MACCULLOCH. Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 67, No. 3, July 2016. copyright Cambridge University Press.

What an interesting article, for which I thank you. As a younger person I often rowed on the Thames, our boathouse being close to Mortlake but on the Northern bank. Whilst admiring and partaking of the views and offerings of The Ship, on the way back home I never realised the portent of the area I was in. Hugely grateful for the enlightenment.

I always think it is a joy to discover something new about an area I thought I knew well. So glad you enjoyed it!

Thanks very much for this. I live in Richmond and was searching for the location of Mortlake Manor, only, with the help of your blog, to find I’d cycled past its wall several times on the Thames towpath. Gripped by the BBC’s wonderful Wolf Hall set.

BTW, Richmond Park as we know it now, didn’t exit in Tudor times. Back then, it was what we now call the Old Deer Park, incl. the golf course and Kew Gardens. Maybe what is now Richmond Park was then part of Mortlake Manor’s domaion?

Hi Nick! Thanks for your comment and the detail about Richmond Park. I don’t know where the boundaries between the domain of Richmond palace ended and where Mortlake’s might have begun. I am sure the information is out there though!