Lords Place: Thomas Cromwell’s Mansion in Lewes

The Rise and Fall of The Priory of St Pancras

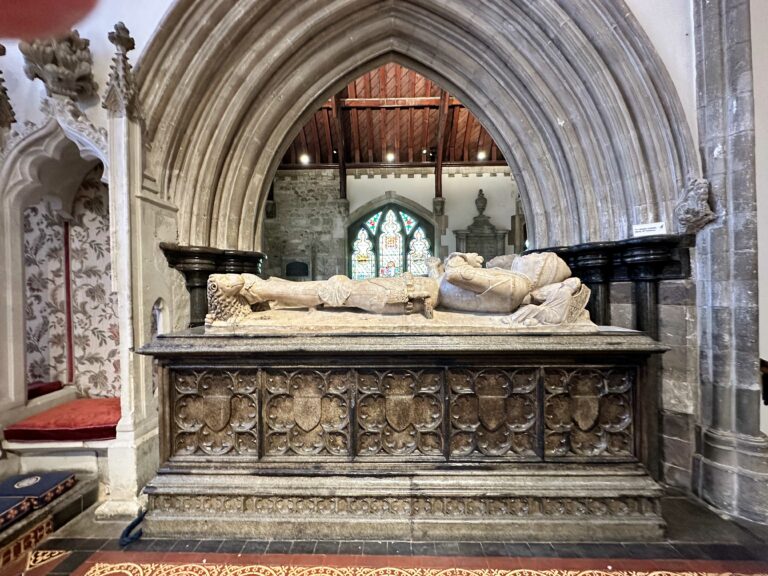

On 16 February 1538, Thomas Cromwell formerly took possession of his latest property acquisition, which, in time, would become known as Lords Place. The Court of Augmentations granted Henry VIII’s Vice Gerent the recently dissolved Priory of Lewes in Sussex. Located around six miles north of England’s south coast, this Cluniac Priory was founded by four monks in 1078 via the wealthy patronage of William de Warenne, a Norman knight who had come to England with William the Conqueror in 1066. William and his wife Gundrada are credited with founding the monastery in Lewes, a daughter house of the influential Abbey of Cluny in Burgundy, France.

In time, this English priory flourished to become one of the largest and most powerful in the country. At its zenith, it was home to around 100 brethren. However, on the eve of the Dissolution, its population had dwindled to just 23 monks and 80 laymen.

The first steps taken to undermine this majestic foundation came in the Autumn of 1535, when ‘the king’s faithful dog’, Richard Layton, arrived at the Priory’s Great Gate tasked with auditing the morals and behaviour of its brethren. Layton did not take long to sniff out the corruption he was searching for. Of course, how much was real and how much was fabricated under pressure is a moot point. However, regardless, Cromwell’s commissioner was soon gleefully writing to his master that:

‘At Lewes, I found corruption of both sorts, and what is worse, treason, for the subprior hath confessed to me treason in his preaching. I have caused him to subscribe his name to it and to submit himself to the king’s mercy. I made him confess that the prior knew of it, and I have declared the prior to be perjured. That done, I laid unto him concealment of treason, called him heinous traitor in the worst names I could devise, he all the time kneeling and making intercession unto me not to utter to you the premises for his undoing; whose words I smally regarded, and commanded him to appear before you at the court on All Hallows Day, wherever the king should happen to be, and bring with him his subprior. When I come to you, I will declare this tragedy to you at large, so that it shall be in your power to do with him what you list.’

Yet, despite this damning indictment, the priory limped on for another two years before it was finally surrendered to the King’s Commissioners in November 1537 by its prior, Robert Crowham. He received a pension and a prebend at Lincoln cathedral, while the monks and lay servants of the priory were pensioned off. Three months later, ownership of the priory and all of its lands were transferred to Thomas Cromwell.

Of course, this was not the only religious establishment the Lord Privy Seal coveted. Two years later, just before his fall in June 1540, Thomas Cromwell was granted the newly dissolved Launde Abbey in Leicestershire, providing a country home in England’s picturesque county of Leicestershire, close to the county border with Rutland.

As always, Cromwell did not take long to implement his plans for the now redundant monastic buildings, which he intended as a home for his son, Gregory and daughter-in-law, Elizabeth, younger sister of Jane Seymour. In line with the usual practice, Thomas earmarked parts of the most high-status residential buildings at the priory to convert into a luxurious family home; these were the Prior’s lodgings and part of its adjoining guest range. The Great Gate of the Priory’s precinct would remain as the principal entrance from the town, while the glorious abbey church and other conventual buildings were to be dismantled.

Redevelopment began immediately. We have already seen that work at Cromwell’s London home, Austin Friars, fell into abeyance for several months while resources were transferred to the work at Lewes. This ‘new’ house would become known as ‘Lords Place’ in time. However, before I describe what is known of Cromwell’s property in Lewes, perhaps we should pause momentarily and imagine the scale of the work on-site.

The systematic dismantling of the vast priory church, the recycling and removal of materials, and the redevelopment of the monastic precinct into suitable Tudor pleasure gardens must have been quite a sight to behold! However, such work was standard practice as nobles and influential men at court all profited from the spoils of the destruction of England’s monastic orders. Other similar redevelopments that immediately come to mind are the Crown’s conversion of the abbot’s lodgings at Dartford, Rochester and York, Sir Richard Rich’s work at Leez Priory and Sir William Kingston’s work at Flaxley Abbey. In other words, creating a fine country house from the most high-status parts of any dissolved abbey or priory was THE thing to do!

The Appearance of Lords Place

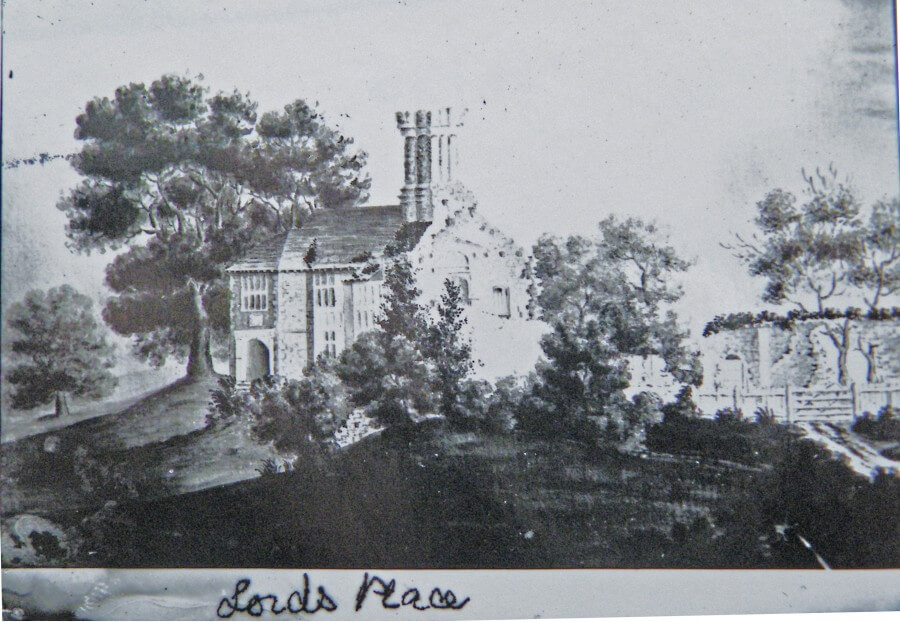

Sadly, as far as I am aware, there are no inventories or detailed descriptions of the house that Gregory and Elizabeth Cromwell had moved into by the Spring of 1538. The most valuable sources come from a couple of basic seventeenth-century drawings of Lords Place before its eventual demise. In addition, there have been extensive archaeological digs on the site of Lewes Priory. This includes unearthing many of the foundations of the priory church when the current railway line was laid through the old priory precinct in the 1840s.

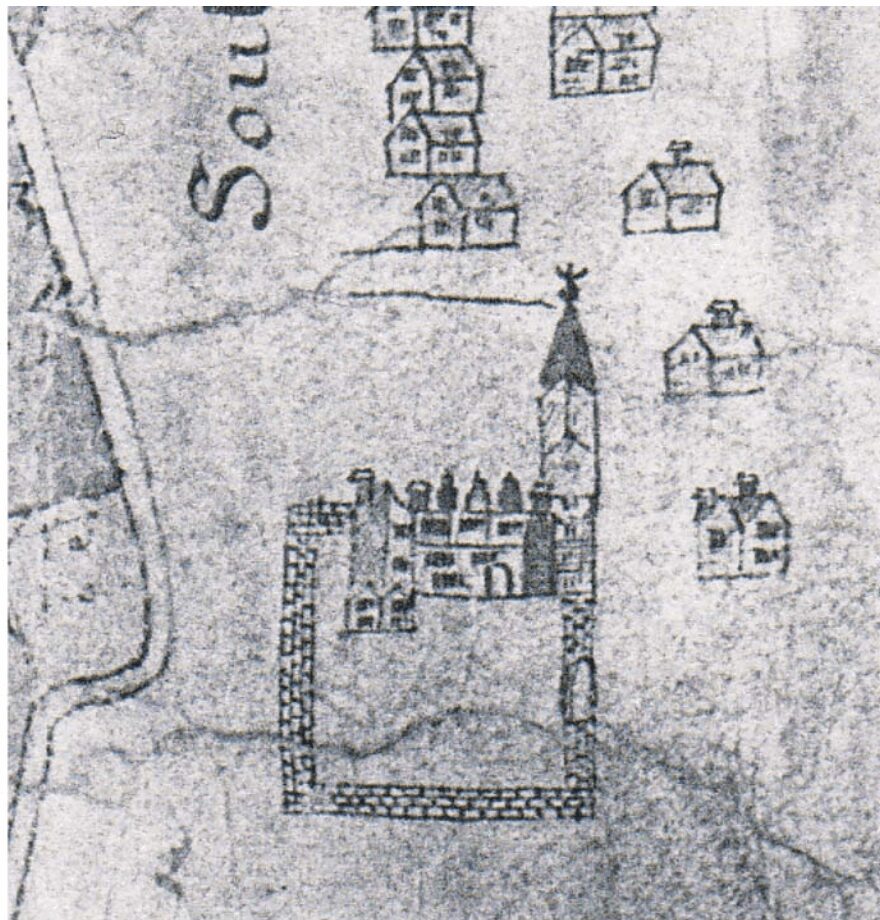

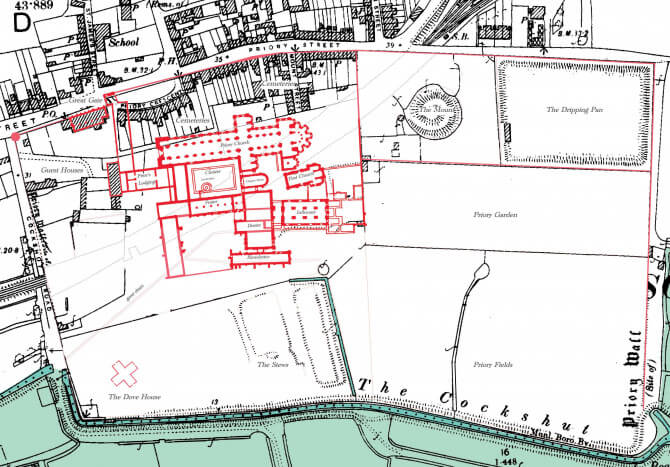

One academic who has written about the Post-Dissolution of the Mansion and Gardens of Lords Place is Paul Everson from English Heritage. Paul has described the Cromwell family home as ‘L-shaped’. When you study the old maps and sketches of Lords Place and compare those sketches with reconstructions of the Priory based on archaeological evidence, you can see this L-shape clearly. However, precisely which elements of the original buildings have been preserved requires a little more guesswork.

Lords Place seems to have comprised a range of buildings, including part of the original Prior’s lodgings that fronted onto the Great Court. Before the priory church was dismantled, this range sat at right angles to the Great West Doors and at the far end of the courtyard from the Great Gate. The guest lodgings that once occupied the west range of the priory cloisters seem to have been wholly preserved, as does a striking tower situated at the southwest corner of the original priory church. Finally, a stump of the southern range of the cloisters (once the priory’s refectory) completed the mansion. The map of 1618 suggests that the footprint of the remainder of the cloister comprised an inner courtyard accessed via an archway running beneath the main west-facing range.

Although Cromwell appears to have intended Lords Place to be a home for his son and daughter-in-law, their time there seems to have been limited. However, we have evidence of their presence in an entry in The Letters and Papers of Henry VIII, dated 24 May 1538. The plague was rife that year, and Cromwell was clearly concerned about the welfare of his family. Evidently, he had dispatched his agent, William Cholmeley, to Lewes to persuade the parish church (adjacent to Lords Place) to desist from burying the dead in the graveyard should it bring disease into the house. William Chomoley writes to Cromwell:

I have received your letters dated at St. James’ the 21st, directed to Mr. Jenyns and me. In Jenyna’ absence, calling to me Mr. Hertwell and Mr. Jeny, your Lordship’s servant, I sent for the honest men of the parish of St. Anne at the town’s end of Lewes, adjoining the parish which has been infected with the great plague, and declared to them your Lordship’s pleasure as to the burial within their churchyard of those who die of the plague. After consulting together half a day and a night, they replied that their parish was free of infection, which they feared would be conveyed with the dead bodies, but Mr. Jeny persuaded them to comply, so that henceforth none shall be buried in the church or churchyard within the precinct of your house here at Lewes. The other parish infected has granted the same…’

Interestingly, this letter also sheds light on two further Cromwell properties close to Lewes. One was called ‘The Motte’, and the other ‘Swanborough’. In the same letter from Master Cholmeley, the properties are considered alternative accommodations for Gregory and Elizabeth during the pestilence. He describes the Motte as ‘being four miles off, a pretty house within your park there’ and goes on to say:

‘…a description [of the Motte] is given in a bill which the bearer carries, and victuals may be conveyed from your house at Lewes. Your bakehouse, brewhouse, slaughterhouse, and pullitrie may be continued. Mr. Gregory rode thither today to view it, and likes the house right well. The other house, called Swanborough, is a mile from Lewes but is thought too little for Mr. Gregory’s company. None have died for eight days, and none are sick of the plague now within the town. I send you a bill of the number of persons to attend on Mr. Gregory on his removal, and of those appointed to be on board wages. Lewes, 24 May.’

The couple survived the epidemic.

In 1539, Cromwell became the constable of Leeds Castle in Kent. This magnificent moated medieval building had long been associated with the Queens of England and was undoubtedly a far grander property than Lord’s Place. Gregory and Elizabeth moved to the castle that year, leaving Lewes behind. Of course, Cromwell was convicted of treason one year later. Any further grand plans he had for Lewes were left unfinished.

Lords Place After Cromwell

After Crowmell’s downfall, the Crown seized all his property and goods, and many were redistributed to other gentlemen at court. Lewes was bestowed upon Anne of Cleves. She retained the property until she died in 1557. At this point, Lord’s Place came into the hands of the Sackville family. Everson believes that it was the second Sackville to own the house, Thomas Sackville (1536-1602), a prominent courtier during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, who further developed the mansion, creating ‘an exceptionally elaborate’ Elizabethan garden.

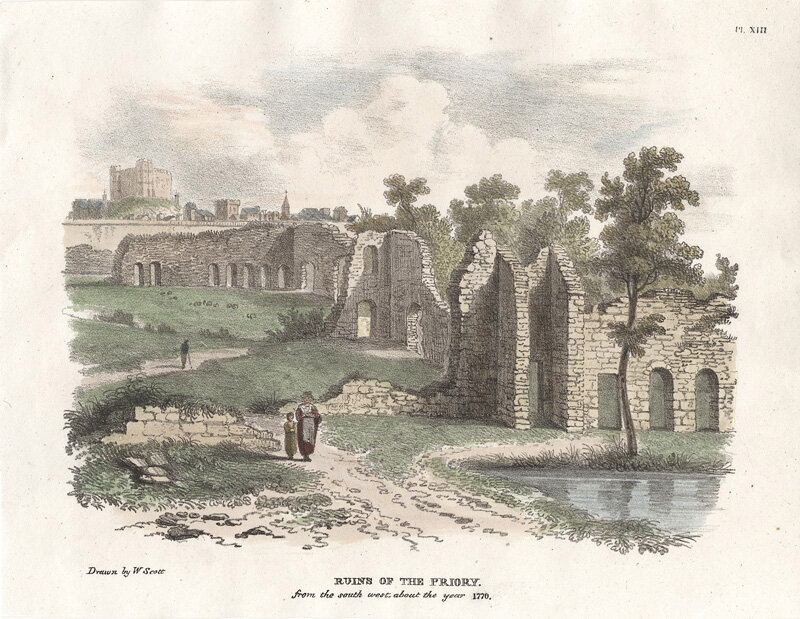

Sadly, the end of the mansion was not far away. It continued to pass through the Sackville family by marriage to the Earls of Thanet. By 1662, due to debt, the house was allowed to become ‘ruinous and useless’ and ‘for the most part fallen downe and lying waste”. Six years later, the formal demolition of the mansion took place. William Lane, Henry Shelley and Edward Trayton were paid £375 for a ten-year lease in 1668, on condition they demolished the ‘great old house’, the great barn and great stable’. Over the next 130 years, what remained was gradually robbed away or decayed until nothing remained of Thomas Cromwell’s ‘Lords Place’ above ground.

Today, the railway line mentioned above cuts directly through the heart of the old priory precinct. Part of it covers the location of the southernmost part of the lost mansion. However, you can visit a park which encompasses a significant portion of the old precinct and view the ragged ruins of fragments of the old abbey.