King’s Place / Brooke House: From Thomas Cromwell’s Ambitions to Wartime Tragedy

Thomas Cromwell’s ownership of King’s Place, later known as Brooke House, was brief—less than a year—but true to form, the King’s wily First Minister didn’t hesitate to invest heavily in its redevelopment. However, before we reach that part of our story, we should acknowledge that King’s Place had an extended and noble history outside this short window in time with a roll-call of significant Tudor owners. It is also the location of a particularly historic moment in Tudor history involving Princess Mary; we shall come to all this shortly.

So, in this blog, we explore what is known about the original late medieval/Tudor manor house acquired by Cromwell in 1535, touch on those illustrious persons of the Tudor court who called it home, both before and after Thomas Cromwell’s tenure of King’s Place, as well as highlighting the significant events that took place there.

Cromwell Acquires King’s Place

In the sixteenth century, King’s Place was a fine manor house situated in the small village of Hackney, just north of London. Cromwell acquired the property from Henry VIII in 1535.

The manor not only commanded stunning views south towards London but was conveniently located only a mile from the home of Ralph Sadler, Cromwell’s ward and protégé. Since Ralph’s stellar rise at court, no doubt facilitated by Cromwell himself, the former had begun building his own swanky house in Hackney (the village of his birth). The house was called ‘Bryck Place‘. Today, it is known as Sutton House.

However, we digress!

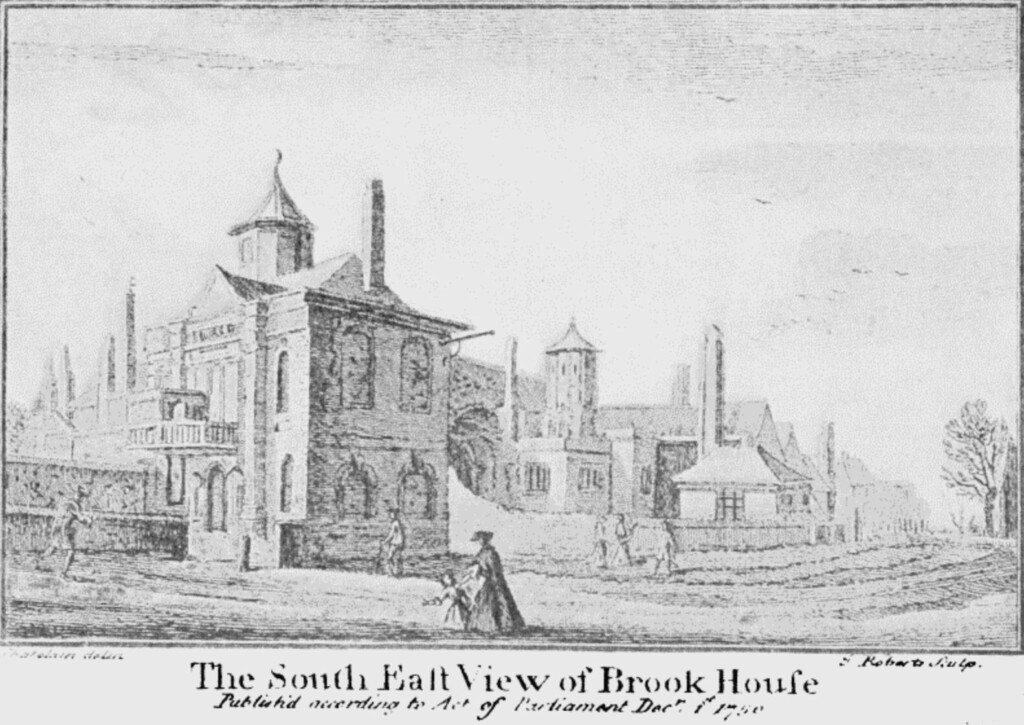

Sadly, having survived for around 500 years, Brooke House was tragically destroyed during a WWII bombing raid. The only shard of fortune to arise from this sorry tale is that having endured so long, its history had been well-preserved through detailed records, early drawings, and, unusually for Cromwell’s properties, later etchings and photographs. These provide more than a glimpse into the manor’s past, including its likely origins.

The Early Origins of King’s Place

In the late medieval period, the manor seems to have been built as a private residence for William Worsley, Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Worsley owned the house for twenty years, between 1476 and 1496, at which point it was sold to Sir Reginald Bray, a behemoth of the early Tudor period. Bray spent most of his adult life serving as Margaret Beaufort’s Receiver General and was an extremely powerful and influential figure at Henry VII’s court until his death in 1503.

The manor then passed through the Southwell family until it was bought by Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, in 1531. Percy is perhaps best known as the early paramour of Anne Boleyn before Henry VIII’s covetous eyes fell upon the lady in question. The Earl owned King’s Place for four years before exchanging it for other lands/property with Henry VIII in 1535. Enter Thomas Cromwell. However, before alighting on Cromwell’s association with the manor, we must return to poor Henry Percy, whose relationship with King’s Place was not yet at an end.

The Earl of Northumberland had long been plagued by a chronic illness marked by fevers and chills; I have read that this was likely attributable to malaria. By the mid-1530s, he was not a well man, already describing himself as ‘diseasid and crased’.

The Earl returned to King’s Place in May 1537, during the second tenure of his ownership of the manor (post-Cromwell) and died there the following month on 30 June, aged 35. Percy had outlived the sweetheart of his younger years, Anne Boleyn, by just 12 months. Still, given the misery surrounding his involvement with Anne, his father’s clear distaste for his son, his subsequent disastrous marriage to Mary Talbot and his chronic illness, one can’t help but think that while born into a privileged position, Henry Percry’s life was a tapestry of misery.

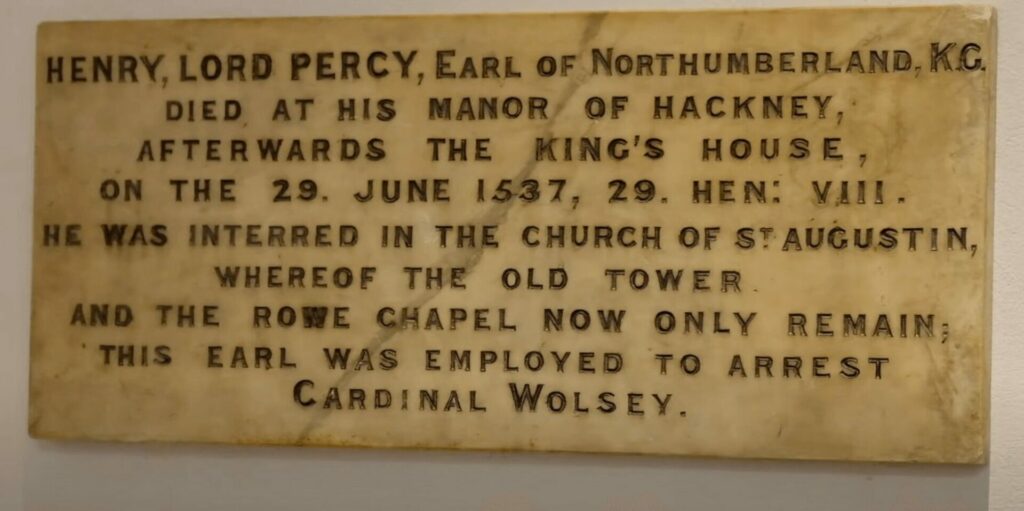

Following Percy’s death, the Earl was buried in the local parish church of St Augustine (now St John’s). A seventeenth-century antiquarian, John Weever, writes in his 1631 treatise on Ancient Funerall Monuments of England that the original epitaph read: ‘Here lieth interred, Henry lord Percy, Earl of Northumberland, knight of the most honourable order of the Garter, who died in this town the last of June 1537, the 29th of HEN VIII’.

Tragically, his grave and much of the original medieval church have since been lost. All that remains in remembrance of Henry Percy is a Victorian plaque fixed to the wall of the chancel. This was discovered during church renovations in 2020 when the decision was made to represent the plaque in memory of the late Lord Percy.

Thomas Cromwell: Property Developer Extraordinaire!

We can now return to September 1535 when Henry VIII granted the manor or principal messuage. According to the Survey of London, published in 1960, the grant was to take effect from the previous March to Cromwell. In May of that year, the King had ordered 50 oaks from Enfield Chase and Park to be delivered to Hackney and employed ‘towardes our buyldynges at our place of Hakney’.The same ‘Survey’ notes that Cromwell did, in fact,. own other property in hackney, so work there cannot be ruled out. However, it is probably fair to say that Brooke House, or King’s Place, would have been far the grander of the two.

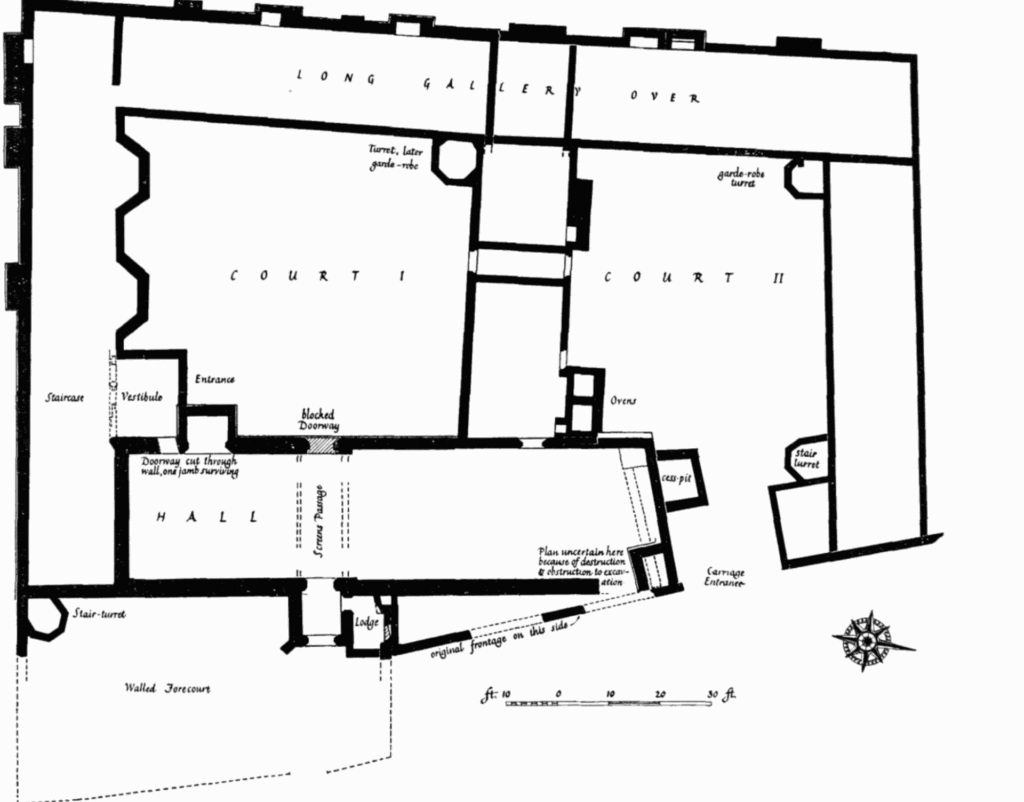

Perched atop a hill, King’s Place offered sweeping views of London and the surrounding countryside. A description of the house survives from an inventory taken in 1547 in the wake of Henry VIII’s death. I have included it in full in the image below.

However, in summary, the house was comprised of outer and inner gatehouses that led to the first of two courtyards. A further gatehouse on the south side of the first courtyard led through to a second. From the plan above, it is clear that this second courtyard could also be accessed directly from the west (front) range of the building.

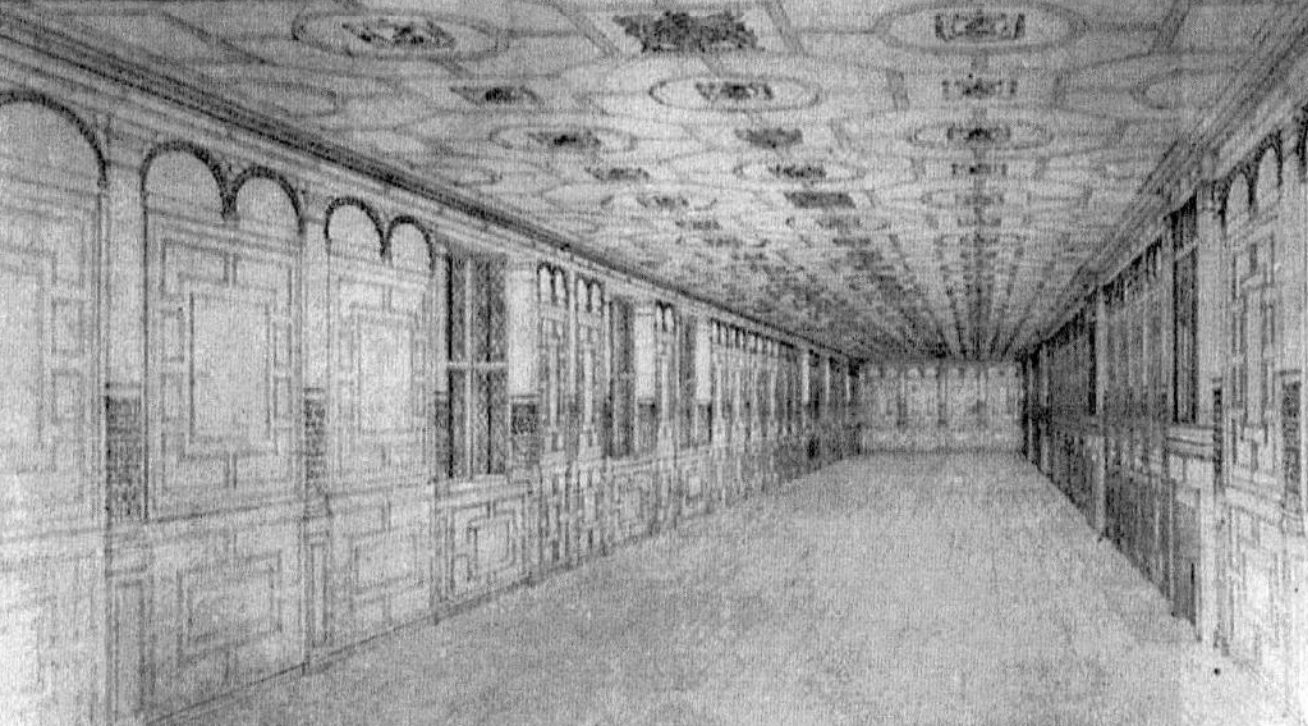

At the time, it was described as a ‘fayre house’ [fayre = beautiful] with a hall, chapel, long gallery, Great Chamber, and various offices. The inner gatehouse was constructed from red brick, while the inner courtyard’s two-storey ranges incorporated timber framing. The long gallery, possibly added later by Lord Hundson, Anne Boleyn’s nephew and a later owner of the house, was particularly noteworthy. Its Renaissance-style plaster ceiling, extending the entire 150-foot length of the gallery, was an exceptional feature and rivalled the celebrated surviving gallery at Haddon Hall.

Cromwell’s ambitious plans for King’s Place were well underway by August 1535. From contemporary letters exchanged between Cromwell and his servants (who kept him updated with regular progress reports), we know that around 60 persons were working at Hackney to complete the renovations. In August, Thomas Thacker reported that the kitchen’s brickwork and chimneys were complete, the buttery and scullery were being expanded, and the lodgings were equipped with new windows, glass, and hangings. Thacker described the property as “a goodly place.”

However, by 3 September, another of Cromwell’s servants, John Wylliamson, notes, ‘I fear your house at Hackney will not be ready in 18 days as I wrote, because of the alterations’. Was Cromwell planning a visit? It is impossible to say. Nevertheless, a week later, on 11 September, Wylliamson writes again to his master, ‘ Your place at Hackney is in good stay, except the garden, which is in digging…I doute not but your maistershipp wyll think yo money well bestowed and shall have as pleysaunt a place as shalbe a greater waye about the Citie of London’. High praise indeed!

Despite Cromwell’s significant investment, as mentioned above, he is not known to have resided at King’s Place, and his tenure was short-lived. Henry VIII reclaimed the manor in the summer of 1536. To any Tudor history lover, the significance of this date is evident. It was, of course, around this time that Master Secretary Cromwell orchestrated the destruction of Anne Boleyn and her five alleged lovers. Subsequently, Henry VIII married his third wife, Jane Seymour, with indecent haste, while Cromwell was rewarded for his efforts in freeing the King from ‘the midnight crow’; he was given Thomas Boleyn’s office of Lord Privy Seal on 2 July and just six days later ennobled as Baron Cromwell of Wimbledon.

Along with the title came the manor of Mortlake. This was wrestled off Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who Henry was likely ‘ticked off’ with for being the sole voice to speak of the late Queen’s virtues. Around the same time, Henry took back King’s Place, and Cromwell’s involvement with the building ended.

A Private Reconciliation

However, in July of that year, the house was the backdrop for an important reconciliation between the King and his estranged daughter, Mary. After months of intense pressure to capitulate to the King’s wishes that Mary renounce her mother as ever being the legitimate Queen of England and therein declare her own bastardy, the young women relented. Anne Boleyn, her arch-enemy, was dead. There was a new Queen, Jane Seymour. It had been five years since Henry had spoken to his wayward daughter, and King’s Place, Hackney, was chosen as the location for the two to meet. Mary is described as being:

‘brought rydinge from Hunsedonne secretly in the nyght to Hacknaye, and [that] afternone the King and the Queene came theder, and there the King spake with his deare an wel beloved daughter Marye, which had not spoken with the Kinge her father in five yere afore, and there she remayned with the Kynge tyll Frydaye ay nyght, and then she roode to Hunsdone agayne secretely.’

Mary’s submission probably broke her heart, but it paved the way for her to reintegrate into court life.

King’s Place After Cromwell

Following Thomas Cromwell’s exit, Henry VIII once more took possession of King’s Place. While Henry Percy seems to have briefly retaken possession in 1537, as we have seen, he was soon cold in his grave. The King visited the manor occasionally, including in 1538, keeping possession of King’s Place until he died in 1547. Thereafter, the house exchanged hands swiftly from Sir William Herbert (1547) to Sir Ralph Sadler (August 1547), who sold it on to Wymond Carew in 1548. The Carews never lived at Hackney; however, the property was grand enough to be leased to Lady Margaret Douglas, Countess of Lennox, Henry VIII’s niece via her mother Margaret, the late Queen of Scotland.

It was to Hackney that the Countess went following her release from the Tower of London in 1575. There, she joined her son, Charles and new daughter-in-law, Elizabeth Cavendish. Charles died at King’s Place the following year, and the Countess followed her son to the grave in 1578.

At this point, the Carews sold the manor to Lord Hundson, Mary Boleyn‘s son and cousin to the then-Queen, Elizabeth I. We can attribute the ceiling of the aforementioned long gallery to this period. Before its loss, it was recorded as sporting the Hundson Arms, lending evidence to the man responsible for its construction. Although Lord Hunsdon only occupied the house for around three years, Henry Carey seems to have made several improvements, including enlarging the gatehouse and building a new water supply.

We now reach the end of the sixteenth century. There was one further owner, Sir Rowland Hayward, twice Lord Mayor of London before it was sold to the final Tudor owners of the manor. Elizabeth, Countess of Oxford and wife to the colourful Edward de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford; they took possession in 1597. Of course, some claim that de Vere was responsible for writing several plays later attributed to William Shakespeare. Edward de Vere died at King’s Place on 24 June 1604 and is also buried (in the graveyard) of St Augustine’s, Hackney’s local parish church.

To complete our tale of King’s Place, we should acknowledge its name change to ‘Brooke House’ in the seventeenth century in honour of its then-owner, Baron Brooke. By the eighteenth century, the house had been converted for use as a lunatic asylum and given a facelift. A grand Georgian facade was added to the property, obscuring its medieval/Tudor appearance from the main road.

However, the end of Brook House came when a German bomb virtually destroyed the building in October 1940. With post-war austerity, neither the cash, nor perhaps the will, was there to rebuild this historic building. However, because of its notable history, as many elements were salvaged as possible from the ruins and the house was carefully demolished in the 1950s; during the process, painstaking records were taken, including an archaeological survey which traced the Tudor footprint of the house.

One of the few remains of the interiors of King’s Place is some late sixteenth-century panelling and fire surround, which was removed from the house before the bombing raid of 1940. The items were installed in the Alex Fitch room of Harrow Public School, where they can still be seen today.

Brooke House, or King’s Place as it was once known, is a poignant reminder of the transience of even the grandest human achievements. This remarkable Tudor manor was touched by the hands of Tudor notables like Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, Henry Percy, and Henry Carey. It bore witness to historic reconciliations, personal tragedies, and the ambitions of those who shaped England’s history. Yet, its ultimate fate—a victim of war’s indiscriminate destruction—is a sobering reflection of the fragility of heritage in the face of conflict. Though Brooke House now exists only in memory, its echoes linger in the painstaking records and salvaged fragments, allowing us to mourn its loss while celebrating the rich tapestry of lives it once sheltered.

Visitor Information:

Sadly, nothing remains above the ground of this once-historic royal abode. However, you can visit St John at Hackney Parish Church to view the commemorative plaque to Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland.

Nearby is Sutton House, which, although developed across the centuries, contains some remarkably well-preserved Tudor chambers once used by Ralph Sadler. The National Trust now owns and cares for the house. You can check out their opening times here.

Sources:

Ernest A Mann, ‘Brooke House: Historical and topographical account‘, in Survey of London Monograph 5, Brooke House, Hackney( London, 1904), British History Online.

W A Eden, Marie P G Draper, W F Grimes, Audrey Williams, ‘Archaeological evidence below ground: Phase II‘, in Survey of London: Volume 28, Brooke House, Hackney (London, 1960), British History Online.

Brooke House: Historic England (online).

Lost Hackney, by Elizabeth Robinson, published by The Hackney Society, 1989.

The Tragic Story of King’s Place: The Home of Edward de Vere from 1597 until his death in 1604, by Elizabeth Imlay. The De Vere Society Newsletter. February 2009.

Ancient funerall monuments within the vnited monarchie of Great Britaine, Ireland, and the islands adiacent, with the dissolued monasteries therein contained: their founders, and what eminent persons haue beene in the same interred. As also the death and buriall of certaine of the bloud royall; the nobilitie and gentrie of these kingdomes entombed in forraine nations, by John Weever. London, Printed by Thomas Harper. 1631.