Elizabeth Somerset (née Browne), 2nd Countess of Worcester

Name and Title: Elizabeth Somerset (née Browne), 2nd Countess of Worcester.

Born: Circa 1502.

Died: Elizabeth died in 1565, between 20 April, when her will was dated and 23 October, when her will was probated.

Buried: St Mary’s Priory, Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales.

Image: Author’s Own.

From York and Lancaster a Tudor Rose: Elizabeth’s Early Years…

Elizabeth Somerset (née ‘Browne’) is probably best known for her association with Anne Boleyn. She was part of Anne’s household and seemingly on intimate and good terms with the Queen. Yet, perversely, the Countess of Worcester has been recorded as one of Anne Boleyn’s first accusers. Before we discuss this part of her story further, let’s touch on what is known of her early life.

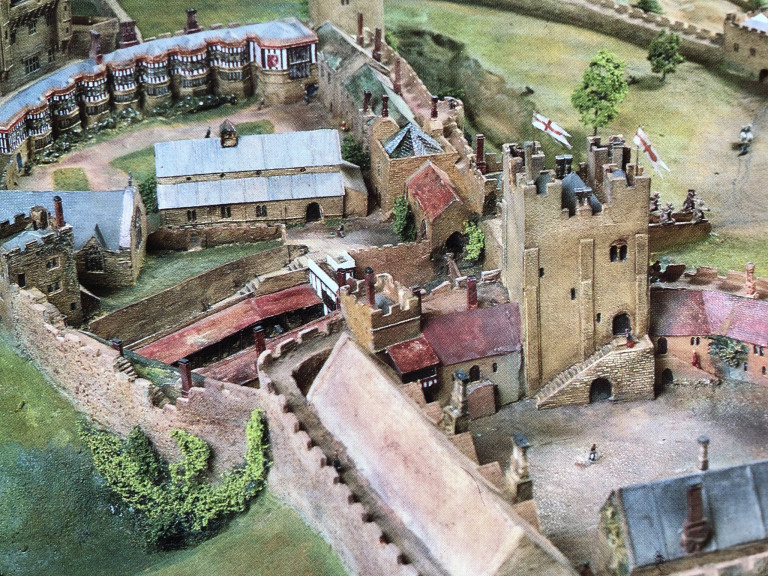

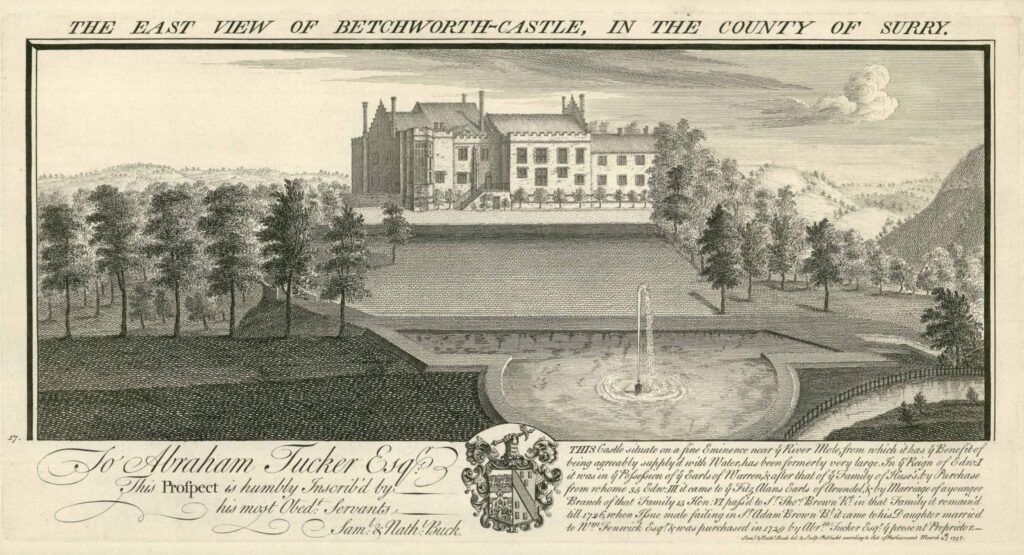

Elizabeth was born at Betchworth Castle in Surrey, the grand country residence of the Browne family. This once fortified, medieval manor house now lies in ruins, engulfed by trees and vegetation, and in the middle of a private golf course. However, as this link shows, it does seem possible to access the site if you are a determined time traveller. It is a journey I have yet to make!

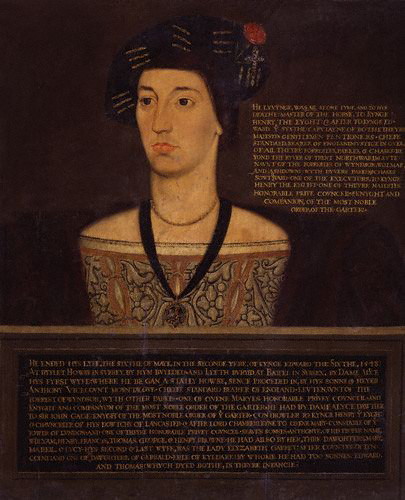

Elizabeth’s precise date of birth seems unknown, but it was probably around 1502. Her parents were Sir Anthony Browne (senior) and Lucy Neville. The former was a standard bearer to Henry VII, Governor of Calais and Steward of Queenborough Castle on the Isle of Sheppey.

Sir Anthony was a Tudor loyalist, while Lucy, Elizabeth’s mother, was a die-hard Yorkist who was reported to have ‘loved the king [Henry VII] not’. That must have made for interesting conversation over the family dinner table! As a result of her loyalties, she was mistrusted by the Tudor Crown but just about managed to keep out of trouble enough to ensure she died a natural death on 25 May 1534, in the sixth decade of her life.

In terms of siblings, Elizabeth had a half-sister from her father’s first marriage, Anne Browne, who married Sir Charles Brandon (a close friend of Henry VIII and later the Duke of Suffolk) around 1508/09. She also had four full siblings: Lucy, William, Henry and Anthony. Anthony was the eldest and, confusingly, in later life, would also become Sir Anthony Browne. Alongside his sister, he, too, would play a crucial role in the downfall of the Boleyn faction in 1536.

Elizabeth, Countess of Worcester, ‘the fyrst accuser’…

By 1527, when Elizabeth was around 25, she married Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester, as his second wife. Their marriage would be fruitful. Elizabeth’s nine (or ten) children were all generally accepted as her husband’s despite the insinuations of 1536 that her morals were questionable.

Image: Author’s Own.

As noted above, Elizabeth’s mother died in 1534. In her will, dated 20 August 1531, her daughter is remembered and includes an ‘Item I bequeath to my daughter countess of Worcester for a remembrance to pray for my soul a pair of bedys of gold with ten gawdies‘.

As a wife of a peer of the realm, it was natural that Elizabeth should serve in the Queen’s household. While she was one of the Chief Mourners at Katherine of Aragon’s funeral in January 1536, she seems also to have had a close personal relationship with the woman who supplanted Henry’s first Queen Consort: Anne Boleyn.

As a married woman of the nobility, the Countess served Anne as a Lady-in-Waiting and was given the honour of standing at the Queen’s left-hand side during her coronation celebration. She was also noted to have been sitting at Anne’s feet during the subsequent coronation feast in Westminster Hall when, according to chroniclers, she held up a fine piece of cloth to hide the Queen’s face should she wish to spit.

Elizabeth was certainly not accorded this privileged position because she was the most senior noblewoman at court; there were certainly others who outranked her. This suggests (to me, at least) that Anne chose the 31-year-old because of their close friendship. This makes Elizabeth’s involvement in what happened three years later even more intriguing—and confusing.

Much of our knowledge about Elizabeth’s relationship with Queen Anne comes from the various letters and papers that survived the chaos of 1536.

As mentioned above, the two women appeared to have been good friends. As early as 1530, when Anne’s position as ‘queen-in-waiting’ was just becoming apparent, the Privy Purse records that Lady Anne ‘rewarded the nurse and midwife of my lady Worcester’ following the safe delivery of one of Elizabeth’s many children. Regardless of whether Anne was born in 1501, 1507 or, as has been postulated recently, around 1504/5, the two women were of similar age, making for a natural affiliation between them.

Furthermore, given the ‘accusations’ made against both of them in April /May 1536, I also wonder if they shared the same joie de vivre and flirtatious sexiness, qualities that drew them together in a shared lust for life. We know that one of Henry VIII’s mistress was a ‘Mistress Browne’. Although there is no definitive proof, this unidentified woman is often said to be ‘our’ Elizabeth. It is easy to see why, if this were the case, the Countess might have been vulnerable to later threats by those determined to rid Henry and England of the ‘goggle-eyed whore’.

The next clue to the intimacy and trust between the two women comes on 8 Apr 1536, when the Countess borrowed £100 from the Queen. We don’t know why Elizabeth Somerset borrowed this money – but it was a huge sum for the time. However, we know of the transaction because of a letter written by Elizabeth to Thomas Cromwell some two years after Anne’s execution; in it, she begs the King’s first minister to refrain from mentioning the debt to her husband, who knew nothing about it.

Image: Author’s Own.

Then we come to the storm that broke as May Day dawned over Tudor England. There appear to be differing accounts of Elizabeth’s involvement in the fall of the Boleyns. One of the principal ones comes from a poem by Lancelot de Carles, dated 2 June 1536. He recorded:

A lord of the Privy Council [her brother, Sir Anthony Browne] seeing clear evidence that his sister loved certain persons with a dishonorable love, admonished her fraternally. She acknowledged her offence, but said it was little in her case in comparison with that of the Queen, as he might ascertain from Mark [Smeaton], declaring that she was guilty of incest with her own brother.

If we believe this account, we can see that Elizabeth did not even try to deny the damning accusations of her own infidelity, suggesting she had at least one affair. Elizabeth was certainly pregnant at the time, and there has long been speculation over whether the father was indeed Elizabeth’s husband or that of her lover.

Image: Author’s Own.

Elizabeth’s involvement in the matter is confirmed by another of her contemporaries, John Hussee. In one of his many gossipy letters to Honor, Lady Lisle, he writes on 24 May that ‘’the fyrst accuser, the lady Worserter, and Nan Cobham with one mayde more… but the lady Worseter was the fyrst grounde‘. A day later he wrote: ‘Tuching the Quenys accusers my lady Worsetter barythe name to be the pryncypall‘.

What is even more perplexing about this whole sorry tale is that Anne Boleyn seemed none the wiser of her friend’s apparent betrayal. From her imprisonment in the Tower, Kingston recorded that ‘my Lady Worcester’ was among those specifically mentioned by the Queen and that she ‘[Anne] myche lamented my lady of Worceter, for by cause that her child did not store [stir] in hyre body. And my wyf [wife] sayd, what shuld be the cause? And she said, for the sorow she toke for me.’ These are clearly the words of someone who cared for her friend’s well-being; presumably, she believed the same was true of the Countess.

So what happened that made Elizabeth ensnare her friend in what most historians now believe was a deadly web of lies? Could this have been a throw-away comment that got well out of hand (as, indeed, Anne Boleyn’s own words about Sir Henry Norris looking for ‘dead man’s shoes’ would be)? Was she threatened by the likes of Cromwell to comply and give sordid evidence against the Queen, perhaps on the promise to cover up her own indiscreet behaviour?

Unfortunately, we do not have enough details to allow us to sift the sordid gossip from actual facts, but, for some reason we can only guess at, Elizabeth threw her erstwhile friend to the lions. Perhaps the child the Countess went on to successfully deliver in September 1536 was named Anne in honour of the late Queen – and to assuage the Countess’ guilty conscience.

The Tomb of Elizabeth Somerset, Countess of Worcester

The grand funerary monument of Henry Somerset, 2nd Earl of Worcester and his Countess, Elizabeth, can be found in St Mary’s Priory, Chepstow in Monmouthshire.

Image: Author’s Own.

The parish church was originally a Benedictine monastery. It was founded in 1072 by William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford, after the Earl established nearby Chepstow Castle; this lies a few hundred metres along the River Wye to the west of the church. Much of the original monastic abbey church and claustral buildings have long since been lost following the priory’s dissolution in 1536. However, the west end, much of the church’s nave, and the truncated north and south transepts survive from the Norman period. This is by far the most interesting part of the church.

The Worcesters’ tomb can be found adjacent to the entrance. However, from my visit, I understand that this was not the original position. The tomb has been moved, possibly more than once. Certainly, we would expect that a monument to such a prominent couple be placed much closer, and often to the side, of the high altar.

The monument itself consists of a tomb chest supporting the effigies of the Earl and Countess, who lie recumbent with their hands brought together in prayer. Pillars carry the tomb’s arched roof, which is surmounted by Somerset’s coat of arms. The tomb is in good condition, although the paintwork is gaudy and lacks finesse; needless to say, it is not original. Given that the tomb has been moved, I doubt very much that the body of Elizabeth Somerset lies either within the chest or beneath it, but I have yet to confirm this is the case.

Visitor Information

To visit Elizabeth’s tomb, you can park in one of the town’s car parks. A small(ish) car park is situated directly in front of the church, or alternatively in the Castle Dell Car Park, adjacent to the castle (where you will also find public toilets). It is a much larger car park and only a 5-minute walk from the church.

The church’s entrance is on the north side of the building, not via the main west doors, which remain firmly closed and may give the impression that the church is not open.

Other Locations Nearby

Chepstow Castle (less than 1 mile)

Tintern Abbey (6 miles)

Raglan Castle (15 miles)

St Mary’s Priory, Abergavenny (23 miles)

Monmouth Priory (17 miles)