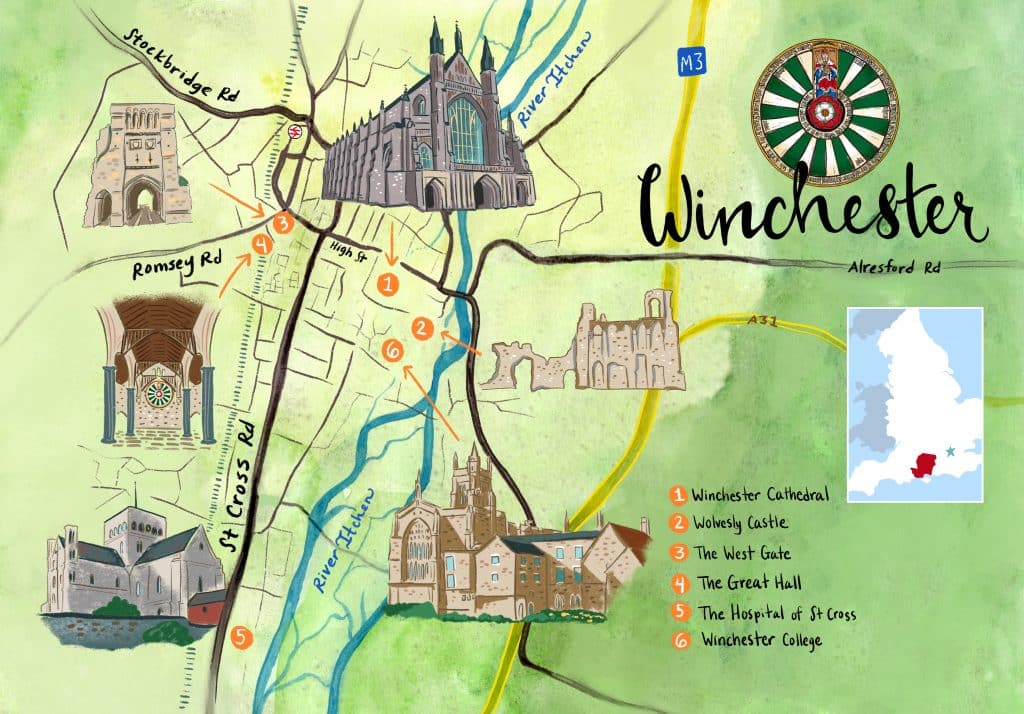

A Weekend in Winchester, Hampshire

Winchester is quite possibly one of the most historic cathedral cities in England. From its pre-history as an Iron Age settlement to the large Roman town of Venta Belgarum; from the Anglo-Saxon capital of the Kingdom of Wessex to the centre of medieval power following the Norman invasion of England, Winchester has been left with deep roots of its historical past.

This means that the city is a history lover’s delight. While there is little to see of the prehistoric and Roman periods, there is still much to be savoured of its medieval and Tudor past. In this guide, we travel to Winchester in Hampshire and highlight some fabulous historical places to visit.

Note: Most of the places covered in this article can easily be reached on foot if you are able-bodied, perhaps with the exception of the Hospital of St Cross, which is a 25-30 minute walk down St. Cross Street or across the water meadows, away from the centre of the city.

Winchester Cathedral

At the heart of this ancient city stands its most recognisable heritage destination: Winchester Cathedral, more accurately known as the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Swithun. This grand Norman Cathedral, which is among the largest of its kind in Northern Europe, is the seat of the Bishop of Winchester.

The current cathedral was started in 1079 and took nearly 500 years to complete. It was the replacement for an earlier Saxon Minster, which lay just north of the present building (which can be seen outlined in the ground adjacent to it). Of course, during this period in England’s history, Winchester was the capital city of the ancient Kingdom of Wessex: the last Saxon kingdom. It is forever associated with its most renowned king, Alfred the Great. His body was initially laid to rest in the Minster after he died in 899.

Before the Dissolution of the Abbey in 1539, Winchester was a Benedictine monastery. It became a secular cathedral in 1542. Today, the abbey church is the only part of the monastic complex to have survived this bloody episode in English history and which can be visited by the public. It is an impressive space. The vast nave has been constructed in the Perpendicular Gothic style. With an overall length of 558 feet (170 m), it is the longest medieval cathedral in the world and the sixth-largest by area in the UK, surpassed only by Liverpool, St Paul’s, York, Westminster (RC) and Lincoln.

One of the outstanding features of the cathedral is its medieval and Tudor chantry chapels. In short, a chantry chapel is defined as ‘…a building on private land or a dedicated area or altar within a parish church or cathedral, set aside or built especially for the performance of the “chantry duties” by the priest’, with the ‘chantry’ being prayers for the dead.

At Winchester, seven chantry chapels were built for seven of its bishops, all added between the 14th and 16th centuries. According to the Winchester Cathedral website, this is more than any other cathedral in the country and reflects ‘Winchester’s’ great power, wealth and royal connections.’ Amongst the star-studded line-up of ancient corpses that you can expect to find are those of Cardinal Beaufort, Bishop Waynflete and Stephen Gardiner, who married Mary I and Philip II of Spain in Winchester Cathedral on 25 July 1554.

The Tudor period saw the last flurry of chantry chapels being built in England. The break from Rome and the move away from the Roman Catholic Church and many of its practices, eventually resulted in chantries being abolished and made illegal. Often their assets were stripped and sold or distributed via Henry VIII’s Court of Augmentations.

Speaking of Henry VIII, we should remember that even before he was born, Henry’s elder brother, Arthur, had been christened in the then abbey church in 1486, after Elizabeth of York gave birth to the heir to the Tudor throne at Winchester Castle. Forty-nine years later, the belligerent, ageing king would assert his authority over Rome by being present in the abbey with Anne Boleyn alongside him. They witnessed the consecration of three Reformist bishops just a couple of months after Henry had executed John Fisher for refusing to sign the Act of Supremacy. This was a monumental ‘up yours’ to the Pope in many ways!

The cathedral is surrounded by a pleasant green, open space, with tree-lined avenues that lead into the adjacent town. You are within a stone’s throw of the city’s shops, cafes and restaurants, which makes Winchester a pleasingly compact destination.

Wolvesey Castle

However, before we put our feet up and enjoy a cuppa, there is much more history to be devoured. A short 5-minute walk from the cathedral will take you to the entrance to Wolvesey Castle (also known as the ‘Old Bishop’s Palace’). To reach the castle from the West doors of the cathedral, you will pass through an area that was once part of the monastic complex of the abbey. This area now houses the Pilgrim School. Look out for the Headmaster’s Lodging along the way. It is a lovely timber-framed house adjacent to Prior’s Gate.

A little beyond that, you will encounter the delightful fourteenth-century Kingsgate. It is one of two surviving medieval gates of the city and was the entrance to the royal palace before the Cathedral Close was enclosed in the tenth century.

Next, you will take a short walk down College Street (passed the house where Jane Austen died for literary fans amongst you). A little further on, 100m or so beyond the main entrance to Winchester College and adjacent to the current Wolvesey Palace, is an inconspicuous gated entrance to a footpath. This footpath runs alongside the Pilgrim’s School playing fields to reach the ruins of the Castle. There is little to announce that you have arrived at the right place, but rest assured, you have!

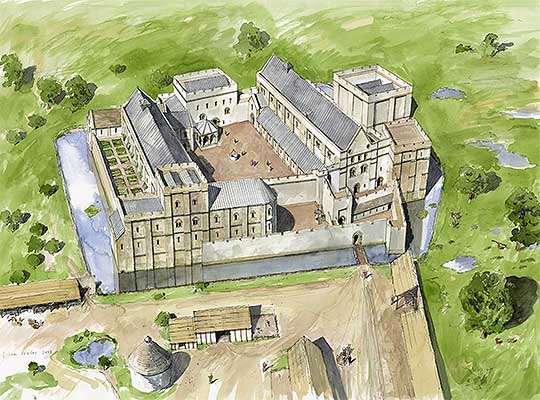

During the medieval and Tudor periods, Wolvesey was a luxurious palace, primarily constructed in the twelfth century by the powerful Bishop Henry of Blois, brother of King Stephen and the grandson of William the Conqueror. It replaced an earlier Anglo-Saxon palace and was extended and refurbished by its subsequent owners.

Empress Matilda laid siege to the palace in 1141. After successfully defending the building, Henry de Blois fortified his residence by constructing two new tower blocks. This gave the palace its castle-like appearance. Hence the name ‘Wolvesley Castle’ came into being.

The principal palace buildings were arranged around an inner courtyard. On either side of that courtyard were the great East and West Halls. There were also domestic buildings and kitchens, a tower and a gatehouse, all surrounded on three sides by a moat.

It is probable that Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn stayed at Wolvesey during their sojourn to Winchester in 1535. If so, the royal guests were likely accommodated in rooms in the west range, as this was used throughout the palace’s life as the Bishop’s principal residence and private apartments. Twenty years later, in 1554, Mary I also stayed in the castle before her wedding to Philip II of Spain. After the service in the cathedral, a grand celebratory feast was held in the East Hall.

Tragically, the palace was largely destroyed during the English Civil War in the seventeenth century. Today, all that remains of the once grand residence of the powerful and wealthy medieval Bishops of Winchester are ruins. A fifteenth-century chapel incorporated into a Baroque palace, built for Bishop George Morley in the seventeenth century, also survives. This building is presently part of the private residence of the Bishop of Winchester and cannot be visited.

Today, the ruins are in the care of English Heritage, but be warned! I tried to visit twice over the winter, only to find the gates locked on both occasions, despite the English Heritage website stating the palace was open. Therefore, to be safe, I suggest visiting the palace during the summer when you have the greatest chance of attaining access.

Westgate

A reasonably short, but hilly, walk up the High Street from the cathedral and the city’s centre brings you to the second of Winchester’s surviving medieval gateways: the Westgate.

The gate was built between the twelfth-fourteenth centuries and stands on the site of earlier gates that date back to Roman times. With hundreds of years of history under its belt, it is unsurprising that the Westgate is now a museum.

While the museum tells the story of the gate as part of the city’s defences and as a sixteenth-seventeenth century debtors’ goal, for Tudor history lovers, one particular artefact makes a visit to the museum worthwhile.

The object of our lust must be the museum’s glorious sixteenth-century painted ceiling. It was commissioned by John White of Winchester College in the mid-sixteenth century to commemorate the marriage of Mary I to Philip II of Spain in 1554. At the time, White was the Warden of the College, although just a couple of months before the wedding, he had been created Bishop of Lincoln. In that role, White was also one of the six bishops officiating at the royal wedding, held at Winchester Cathedral on 25 July.

Ahead of the royal couple’s expected visit to Winchester College, White undertook a spot of home improvements! He seemed keen to renovate and update the Warden’s medieval chambers while paying homage to his new sovereigns. So, John White commissioned the painting of an existing oak ceiling and the insertion of a striking new frieze. Both were painted in the height of Renaissance fashion.

The rediscovery of the ceiling and how it found its way to the museum (along with a fulsome description of its appearance and history) can be found in this excellent article. However, in short, the ceiling includes roundels depicting the busts of both women and men in Tudor garb. White’s initials ‘IW’ are also prominently displayed, alongside various mottos, including ‘Vive Le Roy’, which is painted onto the frieze.

The museum is owned by Hampshire Cultural Trust and is closed during the winter months. Therefore, check out the website to confirm current opening times and book your ticket ahead of your visit (Adult tickets are £3 at the time of writing).

Winchester Castle and the Great Hall

Once upon a time, Winchester was the epicentre of early Norman power in England. After the invasion of the country and its subjugation by William the Conqueror, London did not immediately emerge as the de facto centre of royal power. Instead, riding upon the coattails of the country’s Anglo-Saxon heritage, Winchester initially maintained its dominance as England’s leading city.

Shortly after William took the throne, he reused a plateau of land that had initially been constructed during the Roman occupation of Britain to build an enormous castle. This became one of England’s largest and most significant Norman castles and was the seat of government for over 100 years following the invasion of 1066.

The castle continued to flourish through the medieval period, but by the sixteenth century, its hey-days were over, and it was in decline. During the reign of Elizabeth I, Winchester Castle ceased to be a royal palace but not before it had seen the strategic birth of Prince Arthur at the castle in 1486. Here, we see Henry VII, king of a brand new dynasty, reasserting his right to rule by affiliating himself with the deep roots of England’s noble past.

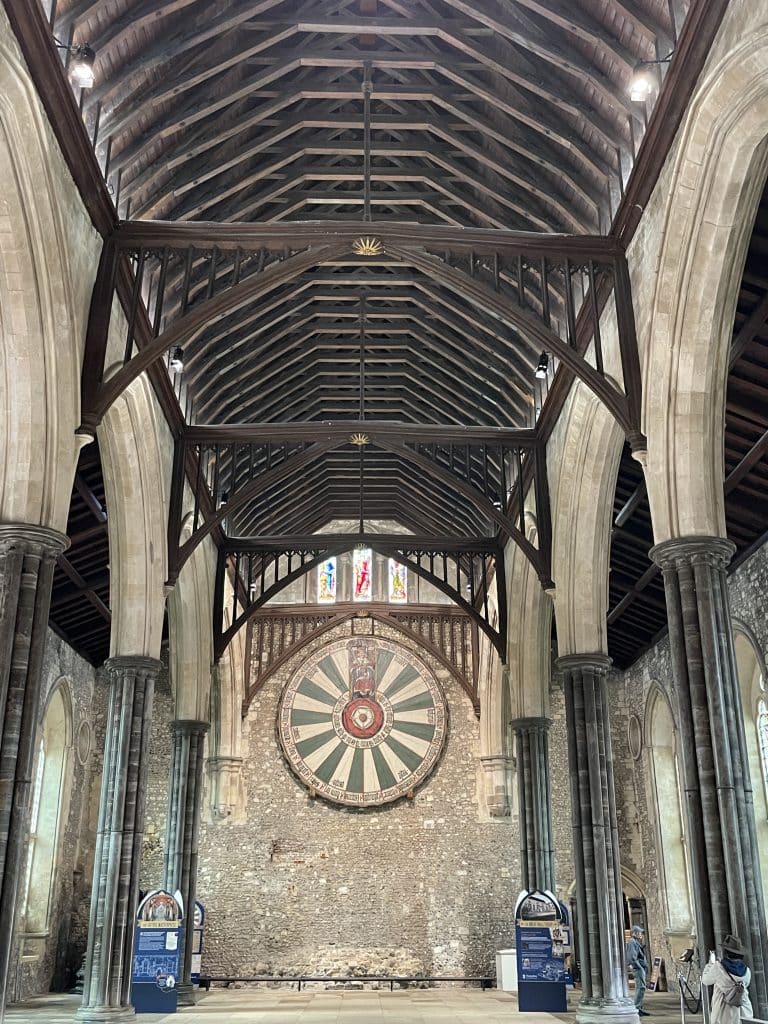

Sadly the only substantial survivor of the medieval castle is its great hall. It measures 110 ft (33.53 m) by 55 ft (16.76 m) by 55 ft (16.76 m) and was constructed between 1222 and 1235 by Henry III, who was also born at Winchester Castle.

I urge you not to miss this gem! The scale of the space is awe-inspiring, with its towering, grey Purbeck marble columns supporting a lofty roof. I addition, it is thought to be very similar in appearance to the now-lost great hall that was once part of the Royal Apartments at the Tower of London. Of course, it was in the latter hall that Anne and George Boleyn were tried for high treason in May 1536. The fact that a ‘sister hall’ survives gives us a chilling insight into how intimidating it must have been for the Queen and her brother to face their accusers in a space filled with around 2000 onlookers.

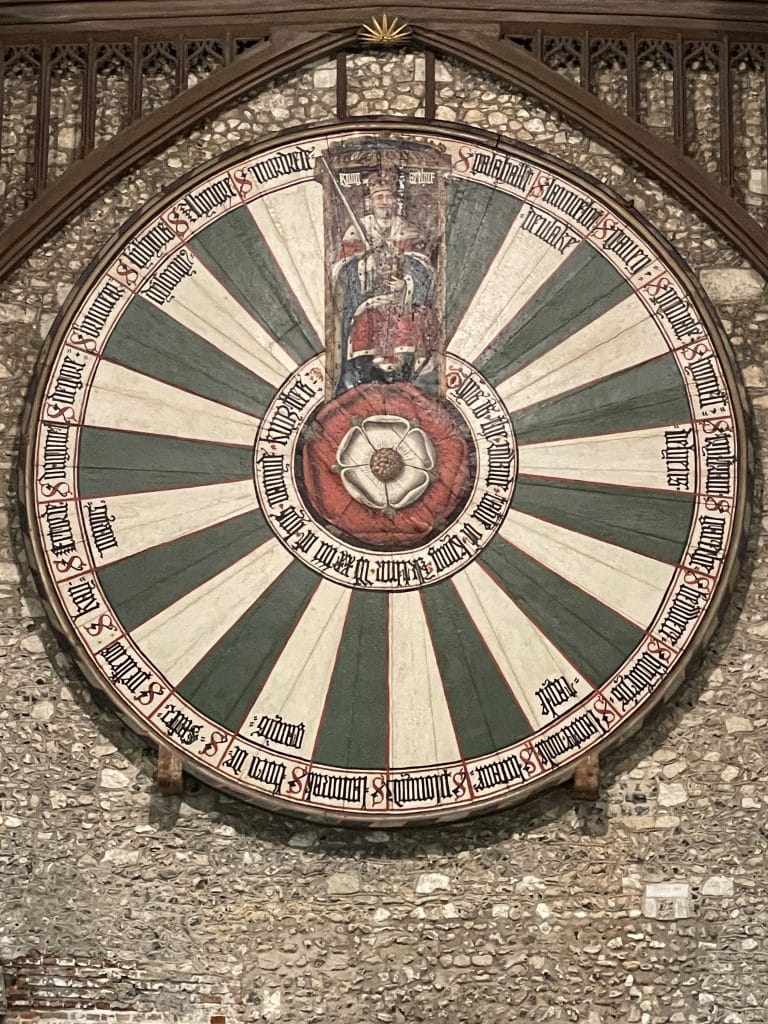

One more artefact is bound to catch your eye: a huge, oak, round table hung on the wall at the high end of the hall. It captures the legend of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table and the fabled Camelot, which Thomas Morley, the fifteenth century author of the Morte D’Arthur, identified as being located at Winchester.

The table was made in the thirteenth century and repainted in the sixteenth for Henry VIII. Clearly, the central figure, meant to represent Arthur, is, in fact, a young version of Henry himself. I often wonder if the table was repainted by the ‘great and the good’ of the city to present to the King during his visit to Winchester in 1535. Umm…a tantalising thought!

You will find Winchester Castle just a stone’s throw from the Westgate. It is managed by Hampshire Country Council and is open all year round, Monday – Sunday, 10 am-5 pm (with that last entry at 4.30 pm). No pre-booking of tickets is required, but for further information, follow this link.

The Hospital of St Cross

Lying just a little further from the city’s centre is the beautiful, medieval Hospital of St Cross. It was established in the 1130s by the powerful Henry de Blois, who was also responsible for building the medieval bishop’s palace adjacent to the cathedral.

Even today, with the encroachment of the modern city, the Hospital of St Cross boasts an idyllic setting. The gleaming Caen limestone of its Norman church rises from the peaceful and lush watermeadows adjacent to the River Itchen. On the day I visited in mid-January, when the sun illuminated a fiercely blue sky, there was not a soul to be seen except the porter overseeing the gift shop and one of the brothers attending to the small garden in front of his almshouse.

Henry de Blois established the Hospital of St Cross as a charitable foundation, an almshouse for thirteen ‘poor men who are so feeble and lacking in strength that they can scarcely, if at all, look after themselves’. They would be fed, clothed and housed until they had regained their health, and then would be ‘dismissed with due honesty and reverence and replaced by someone else’. Charming!

The original lay brothers’ quarters were probably lost at the time of Bishop Waynflete in 1486, when the almshouse struggled to keep going in the wake of the Wars of the Roses. However, the magnificent early Norman church survives and is the centrepiece of the medieval complex, which consists of an outer and even larger inner courtyard, a gatehouse, brethren’s hall and almshouses, along with several ancillary buildings and pleasant gardens. Except for the twelfth-century church, most of the rest of the buildings are of the fourteenth century and are the work of Bishop Beaufort. An eastern ambulatory is largely Tudor in origin.

You can wander unmolested around most of the complex during opening times and will want to linger in the church. This has some incredibly fine Norman architecture on display. Look out for the stone-carved cross on a column in the north aisle. It is angled so that light from a window in the north transept illuminates it on two days of the year. These are 3 May (Invention of the Cross day according to the traditional church calendar) and 14 September (Holy Cross Day). Amazing!

Finally, don’t forget to ask for ‘dole’ as you leave. This tradition goes back to the Hospital’s foundation when wayfarers could expect to receive bread and ale at the gatehouse upon request. You must ask, though. Yes, this is a case of ‘ask, and ye shall receive’! As you munch on your bit of bread and swig down some exceedingly tasty ale, it is remarkable to think that you are continuing a tradition that generations have enjoyed before you. Now that’s what I call living history!

Note: There is limited parking adjacent to the hospital. If you choose to walk, you can either walk 25-30 mins away from the town centre along St Cross Street (the old Roman Road) or via the water meadows from the cathedral, which takes 30 mins. Find out more info on current opening times here.

Finally: Before you leave Winchester, you might also want to squeeze in a guided tour of Winchester College. Founded in 1382, there is some wonderful medieval and Tudor architecture to enjoy and an abundance of history at your fingertips. Tours run on most days and run four times daily from the main gate (except Sunday when only two tours run). The cost at the time of writing was £10 per adult.

Recommendations

Places to Eat:

The Chesil Rectory: It’s the oldest building in Winchester (apart from the cathedral). Apart from its long history, it’s quite beautiful. The food is very good.

The City Mill: This is a working watermill, given as a gift from Queen Mary I in 1554. Now owned by the National Trust, it has a lovely cafe with great cake. What more could you ask for?

The Wykeham Arms: If you just want to quench your thirst after a visit to the cathedral, this is a great place to enjoy a drink while admiring a plethora of fascinating objects that originated in Winchester College.

If you want to catch up with the latest, I can recommend the Instagram account @winchestereats for the best places to eat in the city.

Places to Stay:

The Old Vine: a historic pub opposite the cathedral.The Black Hole: for something a little quirky, The Black Hole is an interesting old building with rooms styled as a prison!