A Long Weekend Away in The Cotswolds

The Cotswolds is an area in western England designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (an AONB). It stretches from just south of Stratford Upon Avon in the north to just south of the City of Bath. Although the area, which is 90 miles long and covers just under 800 square miles, crosses several county boundaries, much of the area lies in the counties of Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire.

The hallmark of the Cotswolds is its picture-perfect chocolate box cottages with thatched or slate roofs and distinctive honey-coloured Cotswold stone. As a tourist, be prepared to drive through lush, rolling hillsides where sheep have roamed the fields for centuries. Indeed, in the Tudor period, the Cotswolds were renowned for supplying the best quality wool in Europe. The taxes provided substantial revenue for the Crown, and it is no wonder Henry VII visited the area several times to cosy up to its most wealthy wool merchants. Two notable Tudor progresses passed through the Cotswolds: the 1502 progress of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York and the 1535 progress of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Both are mentioned in the locations that follow.

Speaking of the vibrant Tudor wool trade, I should mention the subject of the magnificent wool churches, which can be found across the Cotswolds. While this itinerary does not explicitly cover these buildings, as you travel, you may come across oversized churches in tiny villages, such as those in Northleach, Fairford or Burford. These were built on the largess of the area’s wool trade and consequently are known as ‘wool churches’. Always go inside and see if you can find medieval brasses laid into the ground (often hidden under manky carpets to protect them) or tomb chests of the wool merchants of the Cotswolds. I recorded a podcast episode on location in St. John the Baptist in Cirencester and St Mary’s Church in Fairford that touches on this very subject – head to the Podcast page in the dashboard to listen.

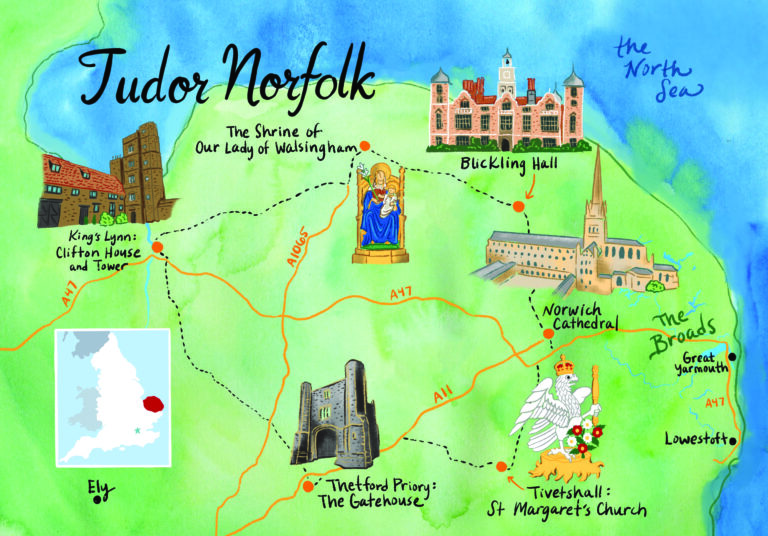

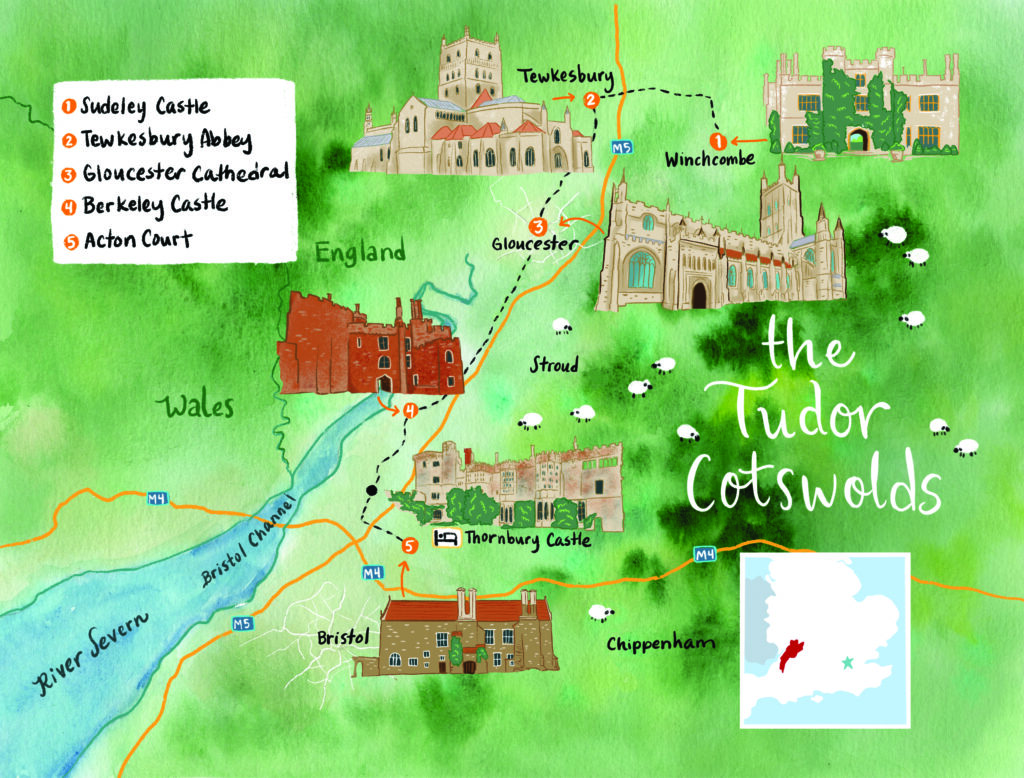

This itinerary could be enjoyed over a long weekend—three days at a push, four at a comfortable pace. We start in the north and wend our way south from Sudeley Castle to Acton Court. Suggestions for historic places to stay are included at the end of this article.

Let’s go time travelling!

Itinerary

DAY ONE

Sudeley Castle and Hailes Abbey

The beautiful Sudeley Castle is nestled deep in the Cotswold Hills, close to the ancient town of Winchcombe. Its mere mention evokes images of Henry VIII’s sixth wife, Katherine Parr, who lived through elation and despair within its rooms, which still pulse with the energy of Tudor personalities and intrigues of the past. Princess Elizabeth, Lady Jane Grey, and Thomas Seymour are among those who’ve called Sudeley home; Henry VIII and his Queen Consort, Anne Boleyn, once roamed its enchanting gardens.

More recently, a five-year archaeological dig within Sudeley’s grounds has revealed an early Tudor garden that witnessed the great post-Armada celebrations laid on for Queen Elizabeth I when she returned to her erstwhile childhood home in 1592.

The castle we see today is mostly Elizabethan. Baron Chandos built it in the late sixteenth century, and the Dent family partially restored it in the mid-nineteenth century. However, its original owner was the Lancastrian loyalist Ralph, Baron Boteler, who constructed Sudeley from local Cotswold Stone as a double-courtyard manor house between 1441 and 1458.

With no heir, Boteler eventually sold the castle to King Edward IV in the 1470s; he, in turn, granted it to his younger brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester. It is believed that Gloucester was responsible for the construction of the lavish east range overlooking the formal gardens. This consisted of three chambers on the ground and first floors. The rooms were lit by a series of magnificent windows glazed with stained glass and warmed by elaborately decorated fireplaces.

While Sudeley can boast a rich history across 600 years and more, it is most often remembered as the last home and final resting place of Katherine Parr, Henry VIII’s sixth Queen Consort. Tragically, Katherine died at Sudeley on 5 September 1548 from puerperal fever, having given birth to her only child, a daughter named Mary, just a few days before. She was buried in the castle’s private chapel a few days later in a Protestant service led by Miles Coverdale.

While her original tomb and the dainty chapel in which it was housed fell into ruins following the slighting of the castle after the English Civil War, painstaking restoration by the Dent family in the 1800s employed some of the finest architects and sculptors of the Victorian era to recreate the chapel and memorial to Katherine. It is a wonderful place to rest awhile and savour the tranquillity of one of the most delightful and romantic destinations on any Tudor history lover’s travel itinerary.

While you are in the area, you may wish to visit nearby Hailes Abbey, the scene of one of the earliest ‘visitations’ orchestrated by Thomas Cromwell, who joined the 1535 progress at Sudeley. It was here that the quarrel over the blood of Christ erupted between the holy men of Hailes and Anne Boleyn. When the vial was inspected by Cromwell’s men and found to contain duck’s blood or some other gooey substance, Anne insisted it be removed. It seems to have been taken away, only to rematerialise sometime later, perhaps when the royal back was turned!

Of course, Hailes Abbey, a major pilgrimage site, was destroyed at the Dissolution. While the abbot’s lodgings were initially turned into a private house, within a couple of hundred years, this too fell into decay, and all that remains are the haunting ruins of England’s once-thriving monastic community.

DAY 2

Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury is a historic town perhaps best known as the backdrop to one of the most decisive battles of the Wars of the Roses in which the Lancastrian heir, Edward, Prince of Wales, was slain, Margaret of Anjou was captured, and the Yorks emerged triumphant. In honour of this event, in July each year, the town plays host to a splendid festival, replete with military encampments and an impressive recreation of the battle.

The town’s main streets are lined with more than a scattering of timber-framed medieval and Tudor buildings. At the same time, its centre is dominated by the abbey church, founded as a Benedictine Abbey in 1087. However, work on the buildings we see today did not commence until 1102, with the abbey being consecrated some 20 years later in 1121.

Inside the church, keep an eye out for the magnificent vaulted roof of the choir, with its gilded Suns of York installed after Edward IV’s crucial victory against the Lancastrian forces in 1471. It is probably no coincidence that the sun in splendour sits directly above the choir floor where Edward, Prince of Wales, was buried.

While exploring this part of the church, be sure to take note of the medieval stained glass in the seven windows that run around the choir behind the high altar. These windows were added in the fourteenth century and are among the most outstanding survivors of their kind in Europe.

Before you leave the abbey, there are a couple of other notable features to look out for. In the north ambulatory, behind the high altar, is a grisly cadaver (or memento mori) monument, designed as a reminder of the mortality of man. The decaying cadaver depicts the corpse being devoured by a worm, a frog, a mouse and a snail! It’s one of my personal favourite tombs of this type.

Nearby, you will see an iron grill on the floor. This leads down to a vault. It is said that the remains of the executed George, Duke of Clarence, brother to Edward IV, are interred here alongside his wife, Isabel.

After exploring the church, head outside to the great west doors. The range of buildings you will find there were built in the early 1500s. An impressive first-floor oriel window is inscribed with the date of its construction: 1509; although being weather-worn, it is difficult to make this out. This range was once part of the abbot’s lodgings. This likely is where Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn would have stayed when visiting the abbey in 1535.

Beyond these buildings is the surviving outer gateway to the former monastic compound. Built around 1500, this gateway is currently leased by The Landmark Trust and available to rent as holiday accommodation.

Before you leave Tewkesbury, take some time to enjoy its mediaeval charms, particularly the Merchant’s House on Church Street. This range of timber-framed buildings has been converted into a museum, recreating the interior of a typical merchant’s house of the Tudor period. Further information on opening times can be found on their website. Do not miss Cornell Books on the High Street if you love old bookshops. You will be lost in there for hours!

Gloucester

During the Medieval and Tudor periods, Gloucester was an important walled city accessed from the four points of the compass by its Medieval gates. A broad high street (whose footprint still exists today) ran east-west through the centre of the town, off which was King Edward’s Gate, the principal gateway to the great Abbey of St Peter (now ‘Gloucester Cathedral’).

The abbey dominated the town and eventually became a magnet for medieval and Tudor kings and those seeking religious sanctity. Henry VII made several visits to the city, and his son, Henry VIII, lodged in the abbot’s lodgings next to the current cathedral when he came on progress to Gloucester in 1535. Anne Boleyn was by the King’s side, and the couple stayed in the city for around a week as guests of Abbot Parker.

Gloucester had deep roots stretching back to the Roman occupation of England. It was later settled by the Vikings and subsequently by Anglo-Saxon nobility. However, the city reached its zenith during the medieval period, when its position close to the English / Welsh border made it an important administrative centre. Furthermore, the deep River Severn allowed large sailing ships direct access to the sea, thus encouraging wool trading in the Cotswolds. At the same time, raw materials such as iron and timber were also plentiful.

Alongside St Peter’s, Gloucester had five other religious houses; one, St Oswald’s Priory, contained a saint’s tomb. St Peter’s itself can boast being the only abbey church outside of Westminster Abbey to host a coronation since the Norman Conquest; Henry III was crowned in Gloucester as a child of nine in 1216.

However, the popularity of Gloucester and its abbey reached a fever pitch following the untimely death (likely murder) of his grandson Edward II in 1327. A good deal of controversy exists regarding the circumstances of Edward’s death (and indeed, whether he did not die but managed to escape overseas). Still, one thing is for sure: a generous helping of retrospective guilt on the part of his vanquisher resulted in the creation of a sublime fourteenth-century tomb replete with the King’s effigy, which later became a pilgrimage site.

Lying close by is the tomb of Abbot Parker. Parker was Abbot of Gloucester during Henry VIII’s and Anne Boleyn’s visit to the city. There are records of him greeting the royal couple on the porch of the abbey and acting as their host during their week-long stay. We know, however, that this tomb is empty. Although you cannot get inside the chantry chapel to inspect the effigy closely, intriguingly, the angel holding the pillow on the right side of the abbot’s head has six fingers, and pomegranates can be seen on the decorative edging around the tomb chest (Katherine of Aragon’s badge). Make of that what you will!

There are so many features to explore in the cathedral that you will want to linger awhile, but be sure to visit Gloucester’s cloisters; undoubtedly, they are the finest in England, replete with an intact lavatorium, where the monks washed their hands before dining. While there, look out for the stained glass in the north aisle. This was removed from nearby Prinknash Abbey in the 1920s. Prinknash was once the country retreat of the Abbot of Gloucester and was likely visited by Elizabeth of York in 1502 and Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in 1535. The stained glass shows the coats of arms of Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon, alongside those of Abbott Parker, Jane Seymour, Edward VI and members of the Brydges family of Coberley Hall. They are easily overlooked!

After exploring the cathedral’s interior, head outside and around the west end of the building to see the medieval gateway, which once led into the inner sanctum of the abbot’s lodgings. Once through the gateway, you will see some lovely old, historic buildings, including a timber-framed building known as ‘The Parliament Room’, part of the original abbey complex.

Sadly, only one wall is surviving of the abbot’s lodgings; this fronts onto Pitt Street. It is the northern wall of the long gallery, and you can see an oriel window, which surely once looked out from the gallery onto the street below. The rest of the abbot’s lodgings burnt down and were demolished in the mid-nineteenth century. King School now stands in its place.

While in Gloucester, be sure to explore the remains of three other monastic houses dissolved in the 1530s: Greyfriars, Blackfriars (which contains a rare scriptorium) and Llanthony Priory. The latter two are particularly fascinating both in terms of their history and architecture. Llanthony Priory, in particular, had close connections with Henry VII via its prior, Henry Deane, who later became Henry’s Archbishop of Canterbury, marrying Prince Arthur to Katherine of Aragon in 1501.

Another Tudor place of note is the Folk of Gloucester Museum, a timber-framed medieval house that now serves as a museum of Gloucester’s history.

Day Three

Berkeley Castle

Berkeley Castle sits perched on a plateau, overlooking a patchwork of fields stretching away below it. Built on a typical Norman motte and bailey design in the eleventh, twelfth and fourteenth centuries, it is also highly distinctive, constructed from local pink, grey and yellow Severn sandstone, with its roofs mainly fashioned in Cotswold stone, slate or lead. Although the sixteenth-century antiquarian, John Leland, described it as ‘no great thing’, it is now appreciated as being in an ‘original and good state of preservation’ and one of the ‘supreme residential survivals of the fourteenth century’, retaining most of its original features down to doors, arrow slits and windows and even iron catches.

Although austere in appearance and with links to the murder of a king (Edward II), Berkeley did not dominate the local town as did some of the mightier Norman fortresses, such as those at Ludlow or Dover. Instead, the less political Berkeley family focused on residential development within a pre-existing buttressed curtilage. In fact, the castle is well screened by the church and trees, such that its full glory can only be appreciated from the south, across the marshy meadows of the diminutive Avon River.

During the early Tudor period, the castle became the property of the Crown thanks to an agreement struck between William, Viscount Berkeley, and Henry VII. The deal was that Viscount Berkeley would receive a marquessate and title of Earl Marshal of England, whilst Henry VII would inherit Berkeley Castle upon the Marquess’ death. This is what transpired, and for the next 60 years, Berkeley Castle was in royal ownership. Perhaps this is why Henry VII and his consort, Elizabeth of York, visited during their fascinating 1502 progress, while Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn placed Berkeley on their itinerary in 1535, when none other than Thomas Cromwell was steward of the castle, managing the estate on behalf of the Crown. Elizabeth I also visited the castle in the late sixteenth century.

After a 60-year hiatus from the end of the fifteenth century to the mid-sixteenth century, the castle was returned to the Berkeley family for the final time following Edward VI’s death in 1553. It is wonderful to think that it remains in the Berkeley family’s hands nearly 500 years later.

When you visit the castle, you feel like you’re strolling through the centuries as you pass from the medieval keep containing the dungeon and the ‘cell’ in which Edward II is said to have been murdered to the magnificent great hall and beyond to reach the homely private apartments, likely occupied by visiting royalty.

The interiors remained largely unaltered from the sixteenth century until the 1920s, when the 8th Earl of Berkeley modernised and extensively altered the internal décor, installing many artefacts from elsewhere. However, what I love about visiting Berkeley Castle is the exceptional state of preservation of the rooms. While the interiors have changed and hardly any furniture survives from before about 1600, the footprint of the rooms, leading from the public space in the Great Hall to the privy chambers beyond, survives. It is easy to let the present dissolve and time slip into the past, imagining yourself in the evening playing dice or cards by flickering candlelight alongside some rather distinguished royal company!

Before we move on, you might want to look out for the sumptuous red cloth decorating the lobby at the head of the stairs. It is sixteenth century in origin, although its provenance is surrounded by mystery. The first version I heard was that the wall hangings were made for Anne and Henry’s bedroom, but they somehow found their way to Berkeley. Did the royal couple leave them behind here after their visit? The other is that they once adorned the royal apartments in Henry’s temporary palace at the Field of Cloth of Gold. Whichever version is true, they are clearly of exceptionally high status, fit for a king, and have been dated to be around 500 years old.

Acton Court

Acton Court is an exquisite example of a courtier’s house from the early Tudor period. It is exceptional in that much of the surviving building remains in a raw state. This makes it one of the most authentic Tudor properties in England and a ‘must-see’ for any Tudor history lover.

The manor house is located close to the village of Iron Acton. It was built in the thirteenth century, although only a fragment remains, notably the eastern wing. This was constructed hurriedly in preparation for a visit by Henry VIII in 1535. Originally, however, the manorial complex contained three ranges, all squeezed within the confines of a moat that entirely surrounded the property.

The person we most associate with Acton Court today is Nicholas Poyntz, courtier to King Henry VIII. His grandfather had been a man of some substance and had served successfully under Henry VII, but it was his grandson, Nicholas, who, as a young man, was ambitious, well-connected and successful. At the time of his inheritance, he was closely connected to Henry VIII’s first minister, Thomas Cromwell and a personal friend of Richard Cromwell and Richard Rich.

All the available evidence suggests that in 1535, in anticipation of a visit by King Henry VIII and his then-wife, Anne Boleyn, Nicholas began an extensive building campaign, lasting until he died in 1556. As no building records survive, the precise date of this massive redevelopment project is based on archaeological, not historical, evidence. This includes the dating of tree-ring samples from roof timbers, which indicate a felling date of the spring of 1535. This, of course, ties in almost precisely with reports of a stay at Acton Court, which was due to take place between Saturday, August 21st, and Monday, August 23rd, of that year.

To accommodate the King and Queen, Poyntz had the entire eastern medieval kitchen range demolished and instead built an accommodation block fit for royalty, including many features considered de rigeur for the time, including an ensuite garderobe connected to the King’s bedroom and interior decoration in the height of Renaissance fashion.

The tragedy of Acton Court is that it was only in the 1970s that the building’s actual historical significance came to light. By this time, it was a wreck and close to collapse. Thankfully, a considerable amount of conservation work has been done on the building since. Although some of the ranges associated with Poytnz’s development of the house are now lost, the east range, the range built to accommodate Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, still survives.

Inside, the first-floor suite remains largely untouched and consists of three great chambers; first, a presence chamber lit by a colossal oriel window sited directly opposite where the King’s throne and Canopy of Estate would have been. Beyond that, in the Privy Chamber was a privy or dining chamber, used privately by the King for dining or entertaining and beyond that, his bedchamber.

This arrangement, unmolested by later incumbents, allows the visitor a fabulous sense of the flow of the chambers from the public to the private. However, within all this, undoubtedly, the house’s outstanding and utterly exceptional feature is the painted frieze, which runs around the upper wall of the privy chamber. This is contemporary to the building of the east range and was created to impress royal guests. It is completed in antick work and is thought to have been executed by a painter of considerable talent, possibly a court painter of French or Italian origin.

You might want to look out for the Tudor graffiti scratched into a window sill on the ground floor. The date? 1589!

Note: Acton Court only opens for three weeks once a year, around June/July. Check out their website for details.

Places to Stay:

There are some wonderful historic places to stay while travelling through the Cotswolds. Here are some of my favourites:

Sudeley Castle Cottages: owned and run by Sudeley Castle, these modern cottages are comfortable, well-appointed, and within walking distance of Sudeley Castle for anyone with reasonable mobility.

Painswick Lodge: Visited by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn during their 1535 progress. One range of the original manor house survives and is now run as a bed and breakfast.

Thornbury Castle: This place needs little introduction! A five-star luxury hotel once home to Jasper Tudor, the current buildings date from the castle’s redevelopment by the 3rd Duke of Buckingham in the early sixteenth century. Of course, Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn also stayed at Thornbury, and you can even book to stay in the bedroom once used by Henry VIII himself.