On the Road to The Field of Cloth of Gold – A Spectacle of Majesty at Canterbury

Last week, I published the first part of a glorious account of the meeting between Henry VIII and Charles V, held in late May 1520, just prior to The Field of Cloth of Gold.

In an attempt to remind his uncle of the power of the Hapsburg Empire, ahead of the meeting between his two rivals (Henry and Francois), Charles made a last-minute dash to England, arriving just in the nick of time. What followed was just over two days of sumptuous religious and secular pomp with festivities held at Canterbury Cathedral and the adjacent Archbishop’s Palace. If you would like to find out what makes this event one of my absolute favourites and why I think it is so interesting, head first to Part One and catch up with the story so far…

If you have already done so, then continue reading to find out what delights lay ahead for those lucky enough to be in attendance and read some of the most lavish accounts of Tudor sartorial elegance you are likely to come across – period.

The Party Continues…

On Whit Monday, 28 May 1520, the whole spectacle of majesty that was detailed in Part One of this blog was repeated. This time, Queen Germain joined Henry, Charles, Katherine and Mary in procession to the Cathedral. Henry waited for the arrival of the Emperor and his entourage by the church door. Upon Charles’s arrival, the King of England ‘placed him [Charles] on the right hand’ and together they processed towards the high altar.

The descriptions of the clothes worn by Henry and Katherine that day are amongst the most detailed that I have read anywhere. So, having read the account below, maybe close your eyes for a moment and imagine the king who:

‘wore a simar, one half of cloth of gold and the other half of grey velvet, with a jewelled belt; the simar was slashed across in about six compartments and joined by a quantity of buttons, all of which were balass rubies, sapphires, diamonds, and other sorts of jewels, and round his neck, he had a jewelled collar, said to be worth more than 10,000 ducats (from what I can make out – and I stand to be corrected by someone who knows better – that’s circa $1.5 million). His cap or bonnet of black velvet was edged and covered with white feathers.

While the queen wore:

‘a petticoat of cloth of gold with a black ground, slashed and laced with gold and black cords, at whose extremities, in lieu of tags, there hung pearls and jewels, her gown being one half of cloth of gold and the other half of violet velvet with a raised pile, the flowers in relief being embroidered with gold thread and pearls. Her head dress was in the Flemish fashion with a long veil and no cap, which gave her additional grace. Round her neck was five large strings of pearls, with a pendant of St. George on horseback slaying the dragon, all in diamonds’.

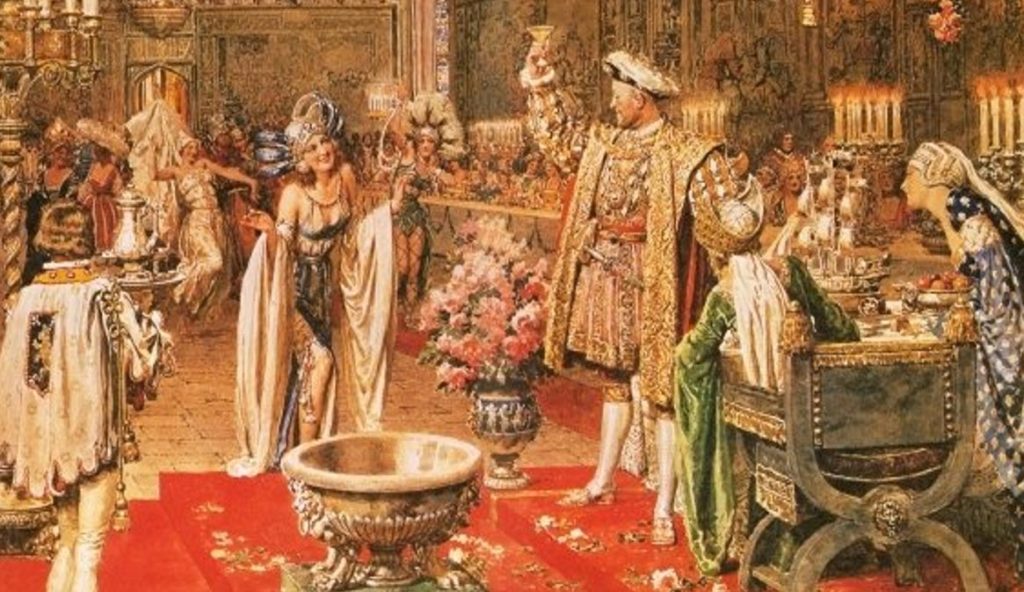

After the Mass, Henry dined with ‘their majesties’ again in private. There was dancing in which Henry participated – ‘although the Emperor did not’. Stamina was the name of the game in Tudor high society. For this was not the only celebration to take place that day. Yet another round of feasting and dancing got underway ‘an hour after dusk’, which at that time of year would have been quite late, maybe around 9-10 pm. There is remarkable detail about the arrival of their Majesties in the great hall, which was ‘richly decorated with arras of cloth of gold and of silk’.

The royal party, including Wolsey, were first offered water to wash their hands in a large gold basin borne by Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. To coin an old joke: how many nobles does it take to help a king wash his hands? Well, three apparently, for while Brandon carried the basin, the Marquis of Brandenburg’s brother and Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, played their parts in pouring out the water!

Afterwards, of the royal party took a seat together at one table, while ‘at a little distance’ from it was placed another ‘very long table, where they (the Venetian ambassadors) sat, as also the French ambassador, and many lords and gentlemen, in number 200’.

At one point the Venetian Ambassador mentions that the tables laid out in the great hall were surrounded by enamoured youths (gioveni innamorati), who stood behind the ladies; and amongst the rest, ‘certain Spaniards played the lovers part so bravely that nothing could have been better’. One of them, the Count of Capra, ‘made love’ so heartily that he had a fainting fit, swooning after his mistress and was carried out by the hands and feet until he recovered himself!

Anyway, if you like to eat quickly, this feast wouldn’t have been for you, as it lasted four hours, after which the tables were removed and the dancing commenced by the Duke of Alva, who was in his 60s but apparently ‘still amorous’. He danced with a Spanish lady, who was his favourite, but according to Surian, ‘not handsome, but beyond measure graceful’.

The ball lasted until it was ‘broad daylight’. Quite a party! So, it is not surprising that on the following day, Tuesday 29 May, the Emperor and the King rested for part of the day, and then sat in council until late in the evening. It was time to talk business. No doubt there was much to discuss ahead of this historic meeting between the heads of state of England and France. However, The Field of Cloth of Gold awaited Henry.

The Field of Cloth of Gold Awaits…

Surian records that at about one hour after sunset, the Emperor left Canterbury, accompanied by the King and Cardinal, with all the rest of the royal retinue following by torchlight. ‘The King [Henry] accompanied him [Charles] a distance of five miles, conversing on the way, and not choosing any of the ambassadors to follow’.

At this point, Henry and Charles took leave of each other. The Emperor, however, was accompanied towards Sandwich by Cardinal Wolsey while the King proceeded to Dover, there to make preparations for his departure to Calais. Charles and Henry would meet once more, after the conclusion of The Field of Cloth of Gold. This time the English would welcome the Emperor at Calais.

And so our glittering tale of a fleeting and unique moment in time comes to an end. Of course, Henry’s entente coridale, sealed with King Francois at the finale of The Field of Cloth of Gold lasted mere months. In the end, this meeting with Charles, and what was to follow in the Pale of Calais, was an integral part of the regal posturing and game playing that embroiled these three monarchs for their entire reigns.

Despite that, one keen-eyed witness was insightful enough to see this spectacle as something worthy of note; something that we, reading about it 500 years into the future, might be interested in. Oh boy! He was not wrong. Thank you, Ambassador Surian!

Source

‘Venice: May 1520, 21-25’, in Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 3, 1520-1526, ed. Rawdon Brown (London, 1869), pp. 14-34. British History Online: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol3/pp14-34 [accessed 8 June 2022].

One Comment