The 1535 Progress, Anne Boleyn and Me: An Adventure in Time!

NOTE: If you are looking for the images associated with this month’s podcast on Berkeley Castle, scroll down until you come to the relevant section covering this location. They are included in this blog covering the Gloucestershire leg of the 1535 progress.

Intoduction

A little later than scheduled, on 8 or 9 July 1535, Henry VIII set out from Windsor Castle in Berkshire on what would become one of the longest and most politically significant progresses of his reign: the 1535 progress. Anne, still the king’s ‘most dere and entierly beloved lawfull wiff’, was at his side, as was Cromwell, the King’s wily secretary.

Letters and Papers setting out the king’s geists, or itinerary, show that the king and queen had planned to travel through the West Country to Bristol before returning to Windsor on 1 October. In the end, the royal couple did not make it to Bristol due to an outbreak of plague in the city. Furthermore, they were to delay their return by almost one month, enjoying the hunting and hawking in Hampshire so much that they did not arrive back at Windsor Castle until Monday, 25 October.

The Beginning of a New Tudor Adventure!

When I began researching the 1535 progress for In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, which I co-wrote with Natalie Grueninger, it felt like I was packing my bags and heading off with the royal couple themselves. Only time and not space separated us as we followed them, visiting location after location along the route of this historic fourteen-week tour.

Some of the places I had visited before. Yet now, armed with details of the events that unfolded at each location around 480 years earlier, I began to see them with fresh eyes. I had never even heard of other locations, let alone visited, such as The King’s Manor at Langley, the Royal Palace at Clarendon and Bramshill. It was to be another fabulous adventure in time!

What makes this progress so significant to any lover of Tudor history – and particularly to Anne Boleyn fans – is that not only was this to be one of the longest and most politically significant progresses of the king’s reign, with the consecration of three reformist bishops as the centre-piece of the progress (a big political statement on the part of the king) but that it was to be Anne’s last summer on Earth.

The Purpose of a Tudor Progress

Before we dive into some of the locations visited during the 1535 progress, let’s consider why progresses happened at all. There were four main reasons. Firstly, there was the need to move out of the monarch’s principal residences, which were sited along the Thames (such as Greenwich, Whitehall, Richmond and Hampton Court Palaces). These were the buildings most intensively inhabited by the court through the rest of the year. Sanitation was limited, and time was required during the year for the palaces to be thoroughly cleaned and repaired; a summer progress away from London provided the perfect opportunity.

Secondly, it was a crucial chance for the monarch to be seen by his or her people. Normally, only the most privileged had access to the king or queen. By leaving the capital and wending their way through the countryside, the peasant population would have the chance to see the monarch – and no doubt be completely awed by the wealth and power on display, as was the intention.

Thirdly, it allowed the court to escape the ‘press’ of the city at a time when pestilence was likely to be most rife and exacerbated by the density of the population in England’s most crowded city: London. Henry was notoriously paranoid about the plague and contagious illness, once even fleeing London for the relative safety of Waltham Abbey at the outbreak of the sweat in 1528, apparently leaving Anne Boleyn behind to fend for herself! The air in the country was considered fresh, clean and wholesome, no doubt largely on account of the relative sparsity of the population.

In fact, in 1535, there was an outbreak of plague in England. Other cities outside of London were also affected, and we see progress being diverted on at least two occasions: once when the royal couple lodged at Thornbury rather than travelling into the city of Bristol, as originally planned, and again when the geists were rejigged at the last minute to avoid the plague around Alton and Farnham in Surrey.

Finally, royal progresses were about pleasure, a chance to unwind from the pressure cooker of court, to be entertained by some of Henry’s aristocratic subjects and to purely delight in a change of scenery.

However, this progress was intended to be more than merely ‘pastime with good companie’. As I have already noted, it had huge political significance. Were Henry and Anne making a point when they departed from Windsor just days after the execution of Sir Thomas More? Bishop Fisher was already dead, and the new Pope, Paul III, was left outraged at Henry’s conduct. The King had executed Fisher only days after the Holy See had created him a cardinal.

Certainly, their itinerary sought to honour landed gentry and courtiers known as ‘reformists’ who had strongly supported the King’s second marriage.

A ceremonial centrepiece of the trip had been masterminded to underline how Henry’s will was clearly bent. This was no doubt heavily influenced by a determined collaboration between Anne and the King’s principal minister, Thomas Cromwell; it was to be the consecration of three hand-picked reformist bishops, Foxe, Hilsey and Latimer, at Winchester Cathedral on 19 September 1535. All were staunch supporters of Anne.

A Leisurely Journey Through Gloucestershire

But before reaching Winchester, Henry and Anne progressed first through Berkshire. They kept moving north, heading first to Oxfordshire and Henry VIII’s most northerly ‘great house’ at Woodstock and its satellite hunting lodge at Langley. From there, the progress turned westwards, crossing the border into Gloucestershire.

Image courtesy of C.J Haldeman

Even today, Gloucestershire is one of the prettiest counties in England. It is covered by a regional area called the Cotswolds, named after the range of rolling hills. The area is characterised by pretty verdant valleys and buildings hewn from honey-coloured Cotswold stone, making for picture-postcard villages.

Taking their time as they passed through the county and often spent a week at each of the major locations they visited, the royal couple lodged at some of the most charming and magnificent historic buildings, now steeped in Tudor history. The first of these was Sudeley Castle.

The 1535 Progress Comes to Sudeley Castle

At the outset of my research, I knew Sudeley Castle well, the first stop on the Gloucestershire leg of the 1535 progress. Of course, Sudeley is famous with lovers of Tudor history for being the final home and resting place of Queen Katherine Parr. Her reconstructed marble tomb lies peacefully beside the high altar of Sudeley’s medieval chapel. However, I was delighted to be able to roam the gardens again and admire the crumbling ruins of the once magnificent east range, built by the future Richard III. As I did so, I imagined Henry and Anne enjoying the beauty and tranquillity of a summer’s evening within the palatial, privy apartments.

Image: Author’s Own

Of course, the 1535 progress wasn’t all about pleasure, at least not for everyone in the royal party. Sudeley was from where Cromwell began sending his men to nearby abbeys and monasteries at the start of the ominous ‘visitations’. Consequently, Hailes Abbey, just three miles from Sudeley, was one of the first abbeys to be ‘audited’ by Cromwell and his officers.

There is nothing more poignant than the ruins of the many dissolved abbeys that litter the English countryside—the scars and reminders of this brief moment in time when religious life in England was being turned upside down in the most seismic way possible—and Hailes Abbey is no exception. It is certainly worthwhile combining a visit there with an exploration of Sudeley Castle.

Tewkesbury and Gloucester Abbeys

The towns of Tewkesbury and Gloucester followed. These settlements were dominated by two great abbeys. This was particularly true at Gloucester, which had four major religious houses and was an important medieval centre in the sixteenth century. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries was complete, like many similar towns and cities whose abbeys were subsequently dissolved, the abbey church was left standing and handed over to the town’s people as their cathedral or parish church. Consequently, in both these cities, we are left with utterly breathtaking monuments to the glory of God, built by our medieval forefathers.

Image Author’s Own

While only fragments of the lodgings used by Henry and Anne survive at both of these locations, the cathedrals into which they were received upon arriving in each of the aforementioned cities survive. Visiting Gloucester is particularly exciting, as during our research, we came across a little-known document recording the details of the visit in 1535. It shed wonderful detail on how the royal couple were welcomed to Gloucester. Most thrilling for me was to uncover the fact that the porch in which Henry and Anne knelt to kiss the cross at the entrance to the cathedral still survives (see the picture above). It was moving to stand there for myself while people came and went around me, unaware of the scene unfolding in my imagination. I know, as a Tudor lover, you will understand!

Berkeley Castle

From Gloucester, I travelled alongside the ghostly court until I was at Berkeley Castle, the next major stop on the progress. Berkeley is an austere building with a dark history, for it is believed that within his cell, the deposed King Edward II was murdered so brutally that his cries could be heard ringing out through the night (you can see his tomb at Gloucester Cathedral).

Image courtesy of C.J Haldeman

However, we digress. With regard to the 1535 progress, imagine my delight to find not only that Berkeley has one of the most magnificent great halls in the country but that the suite of rooms that would have been occupied by Henry and Anne also remains largely intact.

I found this surviving arrangement rare in the locations we researched for the book. Although Berkeley Castle’s early interiors have been lost to later re-modelling, the castle is a great place to get a sense of how the chambers of a high-status house flowed from the public to the private.

One of very few inhabited and fully intact castles in the country, Berkeley Castle remains largely untouched since it was built in stone during the eleventh, twelfth, and fourteenth centuries. It is considered one of the ‘supreme residential survivals of the fourteenth century,’ retaining most of its original features, including doors, arrow slits, windows, and even iron catches.

Distinctive in appearance, it is made from local stone and built on a typical Norman motte and bailey design. The curtilage wall and the substantial thickness of many interior walls mean the castle’s footprint has changed minimally since its construction. However, as discussed in the episode, the interior decoration mostly dates back to its redevelopment by the 8th Earl of Berkeley in the 1920s.

In the late fifteenth century, in a fit of pique to avoid an undesired family member from inheriting the castle, the then Lord Berkley made a deal, passing the Berkeley Estate to the Crown in exchange for a marquessate and title of ‘Earl Marshal of England’. Thus, the castle came under the Crown’s ownership during Tudor times. It was visited not only by Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn in 1535 but also by Henry VII and Elizabeth of York in 1502 and Queen Elizabeth I in 1574.

During Mary I’s reign, the castle was passed back to the Berkeley family and remains their ancestral home. It is open to the public for tours and events and continues to be celebrated as one of the best-preserved medieval castles in England.

In an update to this blog, in 2024, I visited Berkeley to do a podcast recording for The Tudor History & Travel Show. Jane Handoll, one of Berkeley Castle’s guides, took us on a tour around the castle, sharing its 900-year history and, in particular, exploring its Tudor connections. A picture gallery from that visit is shown below. Visitor information for Berkeley Castle is here.

Note: There is unrestricted access to the first half of this podcast here. However, to listen to the full episode, you must be a member of The Ultimate Guide to Exploring Tudor England, The Tudor Travel Guide’s membership site. For more information on the membership, click here.

Berkeley Castle

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

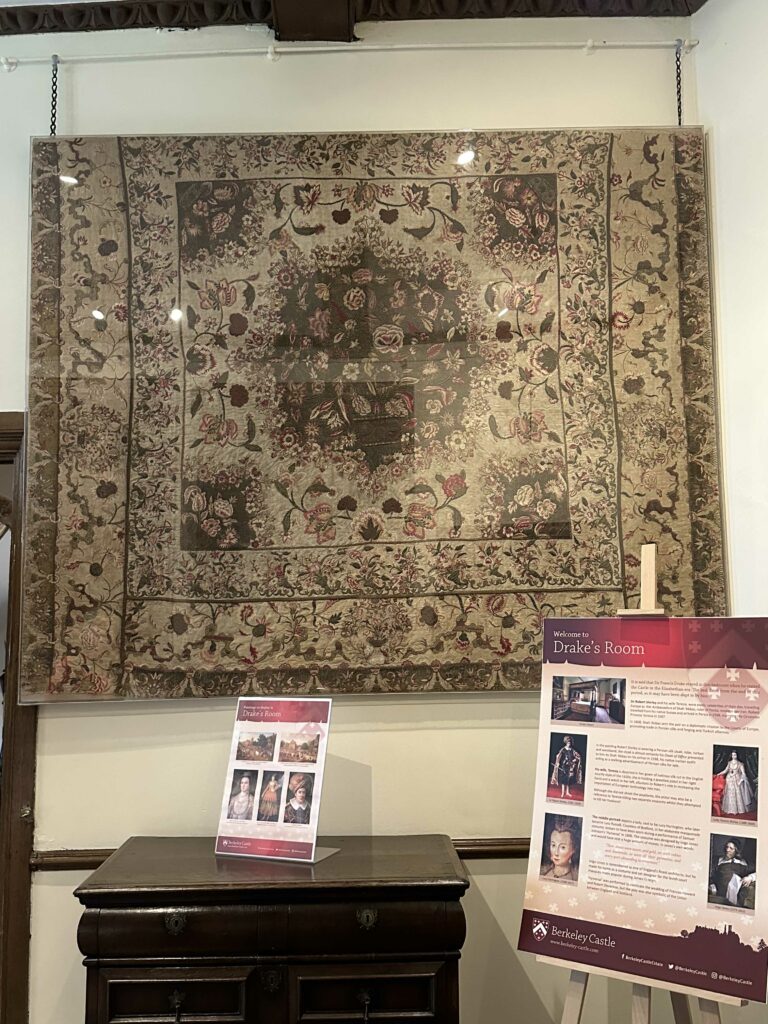

Drake’s room, with a tapestry thought to have been Queen Elizabeth I’s bedspread hanging on one of the walls and a portrait thought to be Elizabeth Carey, Lady Berkeley.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

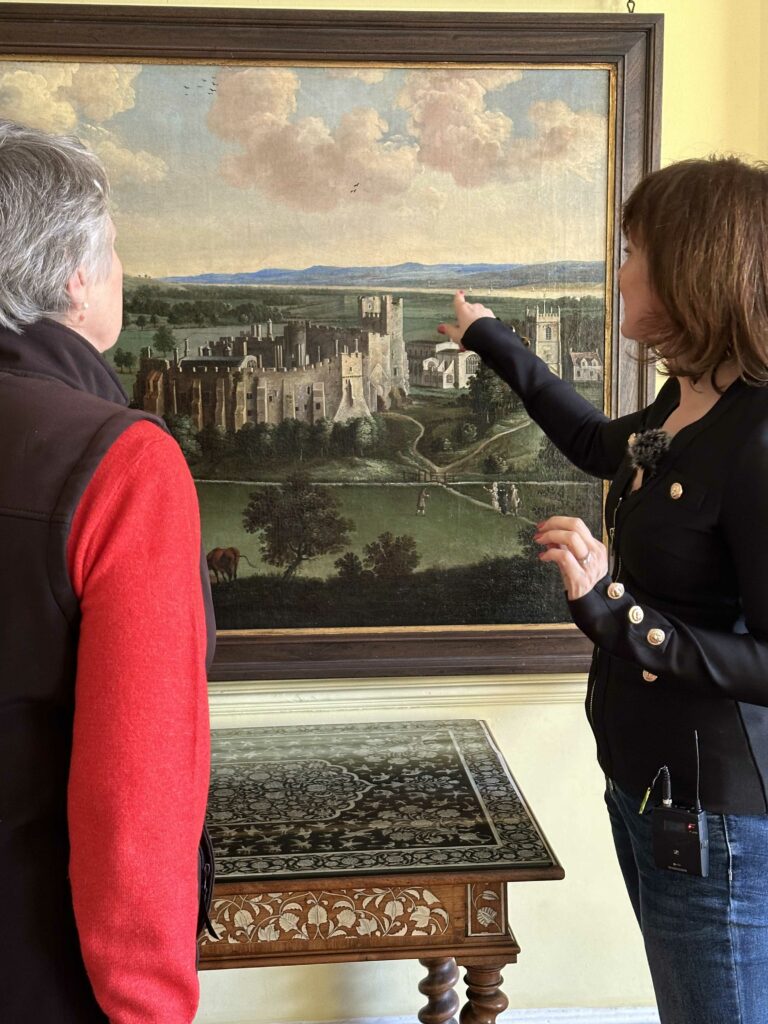

The Picture Gallery displays a collection of fine Dutch paintings, including an early image of Berkeley Castle.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Servant’s Hall

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The kitchen and its spider-web ceiling were built high up to avoid sparks from the three large fireplaces that would have been constantly in use.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Godwin cup was once said to have belonged to Earl Godwin, father of King Harold. It is now thought to possibly date from the late Tudor period and is engraved with Tudor rose, portcullis, harp, and thistle motifs.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Great Hall is 32 feet high and 62 feet long. The stained glass windows depict the family’s various alliances.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The wall coverings date from the sixteenth century.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

The Drawing Room, part of the original privy apartments, which would have been used by visiting royalty, contains a series of wall mirrors.

Sarah and Jane and Sarah and Charles Berkeley, the current owner.

Images © The Tudor Travel Guide.

Thornbury Castle

Just a short distance further south lies Thornbury Castle. In Anne’s day, as now, a grand Tudor house still stands, although it remains incomplete on account of the execution of the man who once owned it, the Duke of Buckingham. Nevertheless, the Duke did manage to create a fine country house that was used by Henry and Anne during a week-long stay. Here, they received delegations from the nearby city of Bristol.

Today, Thornbury is a unique hotel; you can stay in the octagonal room in one of the towers where Henry once laid his head at night. The gardens in summer are delightful, and I have happy memories of enjoying a thoroughly delightful cream tea and a glass of champagne with my co-author, Natalie Grueninger, as we mused on what we might have witnessed had we been there around 500 years earlier.

Acton Court Hosts the 1535 Progress

Acton Court was next on the 1535 itinerary, home of Sir Nicolas Poyntz and his family. You can read and listen to me talking about Acton Court here. It is one of those places that relatively few Tudor lovers get to see. Opening times are severely restricted, and, for many, it is well off the tourist trail.

Imagine my delight at having a personal tour with Natalie of this incredible building: one of the most authentic early Tudor manor houses in England! Because of its raw state, it is easy to imagine the chambers as they once were and to see the royal party enjoying the newly constructed lodgings decorated in the height of Renaissance style. It is very special indeed!

After leaving Acton Court, the progress continued through Wiltshire, Hampshire and Surrey before returning to Windsor Castle in early October. The royal couple dallied in Hampshire amongst some of the best hunting grounds in the country. And take pleasure they seemed to do; three letters note that ‘the King and Queen are merry’. And indeed, if we calculate backwards from Anne’s fateful miscarriage on 29 January 1536, we find ourselves somewhere between Salisbury and Easthampstead in the latter part of the 1535 progress. Of course, four months after that miscarriage, Anne Boleyn was dead at the hands of the Swordsman of Calais.

Not every place Henry and Anne lodged during the 1535 progress remains standing. In some instances, like Thruxton or Woodstock, only grassy earthworks remain where the manor house once stood. At others, crumbling ruins still cling to the landscape, like at Clarendon, just outside Salisbury. Yet, visiting all the known locations was like opening a Tudor treasure trove. There was something extraordinarily special about completing a journey, linking one place to the next, bringing me as close to Anne Boleyn as I had ever felt.

Useful Links

The 1502 Progress: Berkeley Castle (for members of The Ultimate Guide to Exploring Tudor England only). To find out more about joining the membership, click here.

Visitor information for Gloucester Cathedral, home of the tomb of Edward II, is here.

Wonderful as always Sarah!! Thank you for this blog!!

Thanks, Mark!

Really enjoyed reading that Sarah, as I did the podcasts. You bring the period to life.

Thank you kindly, my lady!

Very interesting and detailed. As I understand it, Anne Boleyn and Henry never went west of Bristol. Is that correct ?

Hi Kevin, thanks for the feedback! Glad you enjoyed it. Anyway, you are correct. They never went deeper into the south-west.

Enjoyed reading this, would love in future to come on such a trip! “

I hope to welcome you on our tour one day!

Very enjoyable , I am into real Tudor history not the so called lovie version’s

Thank you!

Natalie, I read this article right before I visited Gloucester Cathedral in June, and while I too walked through the porch, I wasn’t sure if I missed the cross that Anne kissed. Where should I have been looking? Do you know if it is still there? If you know more– even if it was a cross brought out for them to kiss– please share. I am very curious, but wanted to make sure I understood the story before I emailed the Cathedral with questions. Thanks!

Hi Melanie! It’s Sarah here. The Tudor Travel Guide. The cross would have been offered by the abbot for the couple to kiss – a standard procedure it turns out from my ongoing research into Tudor progresses. I suspect like a lot of pre-reformation church artefacts, that cross is long gone – possibly melted down. Maybe a victim of the Dissolution, maybe of the Civil War. I don’t know. I have visited the cathedral and spent time with the cathedral archivist and seen several treasures that they hold from the 16th century and earlier. However, I never specifically asked them if the cross survives. Feel free to enquire. If it turns out a 16th century cross survives, of course, we couldn’t be sure it was that one used on that day. Thanks for the question!

Great explanation, Sarah. Thanks for your reply.