York, North Yorkshire

Distance from Clerkenwell, London: 294 miles

‘And you need to warn William Gogyne and his fellows to go easy on the wine for now, for everyone says that the town shall be drunk as dry as York when the king was there.’ William Paston III

Having left Pontefract on 22 April, the king headed northwards, pressing on to reach the apex of his northern progress: the ancient City of York. Of course, York was the capital of the North and the heartland of the royal house whose name was synonymous with the city. Two mighty castles, whose history remains inextricably tied with that of the House of York, lie in the county. The first, Sheriff Hutton is situated just 10 miles to the north of the city, while the second, Middleham Castle, lies deep in the rugged landscape of the Yorkshire Dales, about 45 miles north-west of York.

Sheriff Hutton was the original headquarters of the Council of the North before it was moved to York after the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539. Situated within easy reach of the city, Sheriff Hutton Castle was a powerbase for Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III). That can be seen in Richard’s decision to send his niece, Elizabeth of York, and her sisters to Sheriff Hutton for safety while awaiting news of Henry Tudor’s invasion of English shores.

The second, Middleham Castle, is still known today as the childhood home of Richard III. He grew up at the castle under the guardianship of his powerful uncle, Richard Neville ‘The Kingmaker’. Richard’s son, Edward, would also be born at the castle in 1473 (or possibly 1476) and subsequently died there in 1484, just a year before Richard was slain at the Battle of Bosworth.

A Brief History of York

The ancient City of York is a medieval jewel, the gateway to the rugged but poetic beauty of North Yorkshire’s dales and moorlands. After the Romans established the fortress town of Eboracum in the first century AD, the city went through periods of decline and revival until, in the ninth century, it became firmly established as the Viking capital of the north, Jorvick.

Situated on the banks of the navigable River Ouse, Jorvick soon became an important northern trading post, prospering through the Middle Ages as the port grew in importance. We can imagine sailing ships docking on the quay, bringing fine wines from Europe while, increasingly, craftsmen flocked to find work in a city that had become noted for its wool and leather trade.

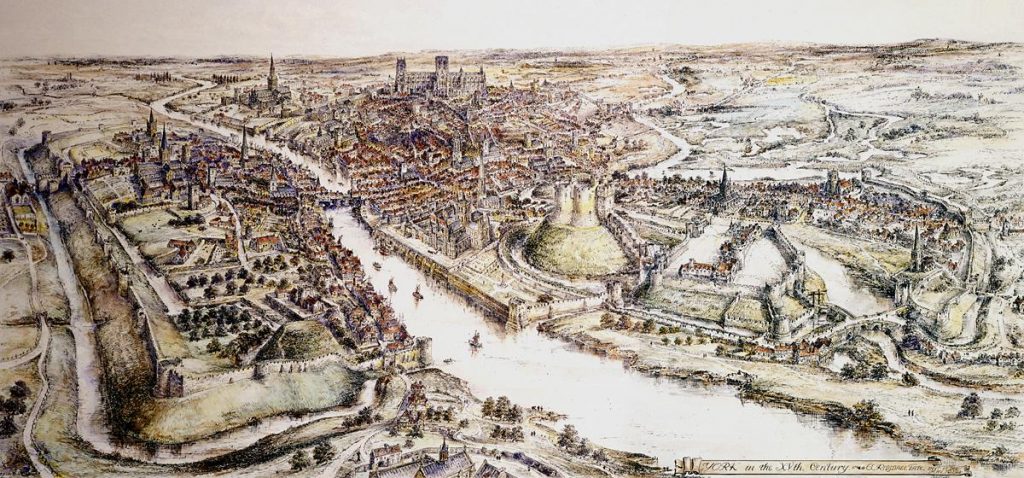

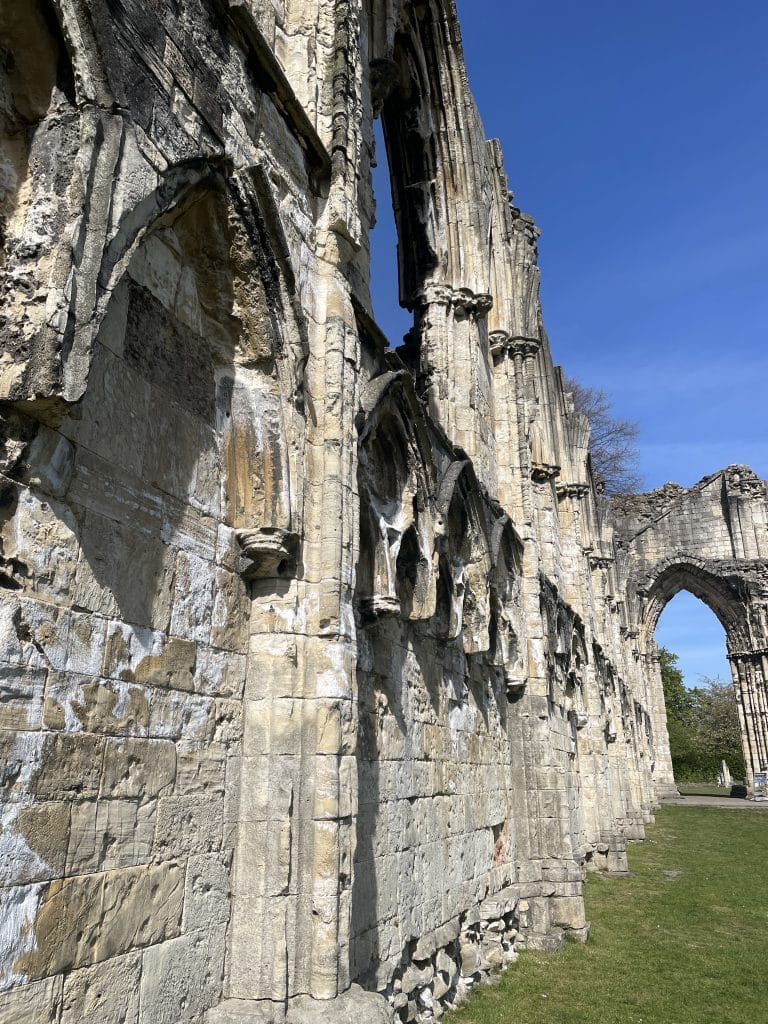

By the time of Henry VII’s visit, the great medieval buildings of York, such as its Gothic Minster and the powerful Abbey of St Mary’s, were established. They must have defined the skyline of a city whose cramped medieval streets had long ago begun to spill over its confining walls, such that York, as it was by then known, enclosed ‘extensive areas of pasture, gardens and orchards’.

The walls were punctuated with four ‘gates’ that could be barred against anyone trying to invade the city. Today, York still retains all four of these gates; thus, the walls are ‘the most complete example in England’.

Henry VII’s Arrival at York

Around 15 miles north of Pontefract, the king and his retinue reached the small town of Tadcaster, once a Roman fort and, even in the fifteenth century, the site of a long-ruined medieval castle. Apart from this feature, the other significant landmark of the town was its ancient bridge. John Leland helpfully leaves behind a description of Tadcaster, its surroundings and landmarks in his Itinerary.

From that description, we can imagine the royal cavalcade making its way along the road into Tadcaster, surrounded by a landscape comprising of ‘good corne and pasture ground and sum[some] woode’. The king was dressed in a gown of cloth of gold and ermine. Riding upon his courser, he must have been a splendid sight as the town’s folk of Tadcaster thronged the streets to catch a glimpse of their new Tudor monarch.

Leland notes in his Itinerary that the ruins of Tadcaster Castle stood ‘a little above the bridge’ and that ‘it semith by the plot that it was a right stately thing’, while the bridge itself ‘hath 8. faire arches of stone’ and made for a ‘good thorough fare’. Leland noted that some of the townsfolk believed the bridge to have been constructed by stone robbed from the castle, which had long since been derelict.

The Herald’s Memoir describes how Henry was met at the ‘further ende’ of Tadcaster Bridge, which formed the ancient boundary of York’s franchises. Here the sheriffs of York gathered with their white staffs of office in hand to greet and escort the King towards the city. Of course, we have already seen a similar ceremony when Henry was greeted upon his arrival at Lincoln and Nottingham.

Henry was about to reach the pinnacle of his journey and the centrepiece of his progress. Anyone wishing to take a direct route to York during the late medieval period needed to travel along the old Roman road, which headed north out of Tadcaster. The Herald tells us that the King progressed along this route until he was ‘iii[3] myles out of York, at the City’s boundary. Here, Henry VII was met by the mayor and ‘his bretheren’ along with a significant number of York’s citizens, who awaited the king on horseback.

A map of the medieval city contained in Angelo Raine’s book, also called Medieval York, shows the position of this boundary. It lay close to where North Lane joined Tadcaster Road. Adjacent to the road stood the Chase Hotel; a little further on, there were Tyburn’s gallows (not to be confused with the more famous Tyburn gallows in London).

To welcome Henry, John Vavasour made an appropriate speech ‘bidding the king welcome and also recommaundede [recommended] the citie and the inhabitauntes of the same to his good grace’. Interestingly, John Vavasour owned land and a manor house adjacent to where the Battle of Towton took place in 1461, just a couple of miles outside Tadcaster. He had fought for the Yorks, who had emerged victorious. Thus, Vavasour had not been the King’s choice for this task, although he would later win Henry over by quashing the rebellion led by the Earl of Lincoln the following year, in 1487.

Speeches complete, the procession moved forward.

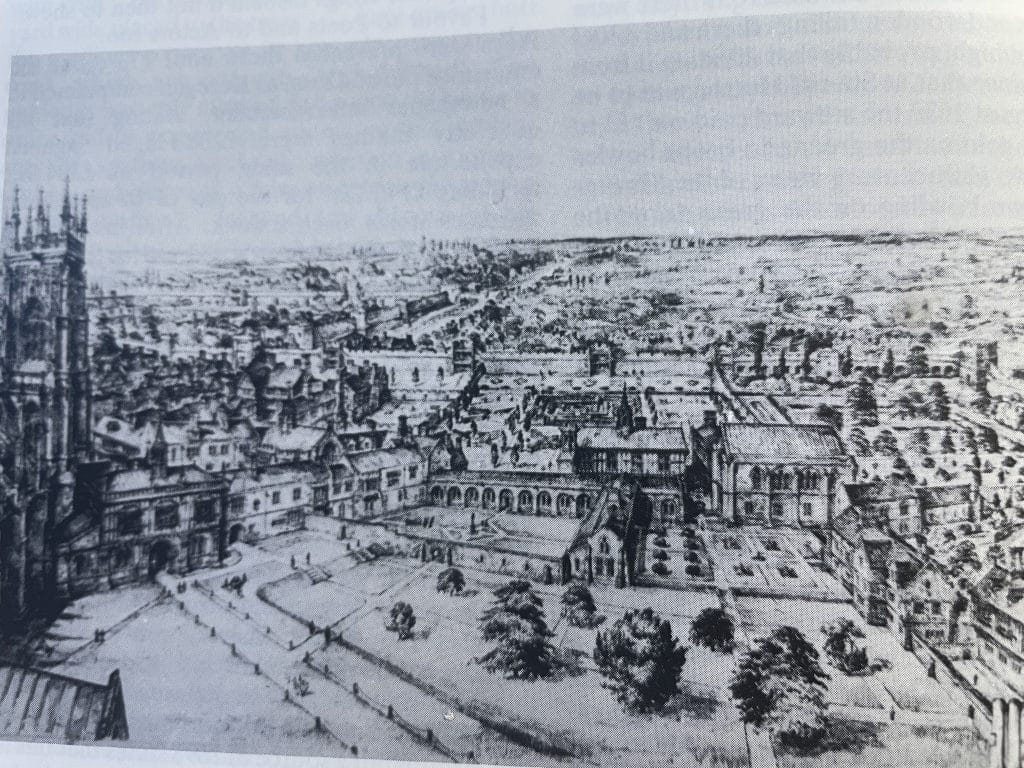

A wonderful, pre-industrial age etching shows York from the south-west, perfectly capturing the sight that would have greeted the royal party as they snaked their way along the Tadcaster Road toward the city’s entry point on the south side: Micklegate Bar.

Tudor York

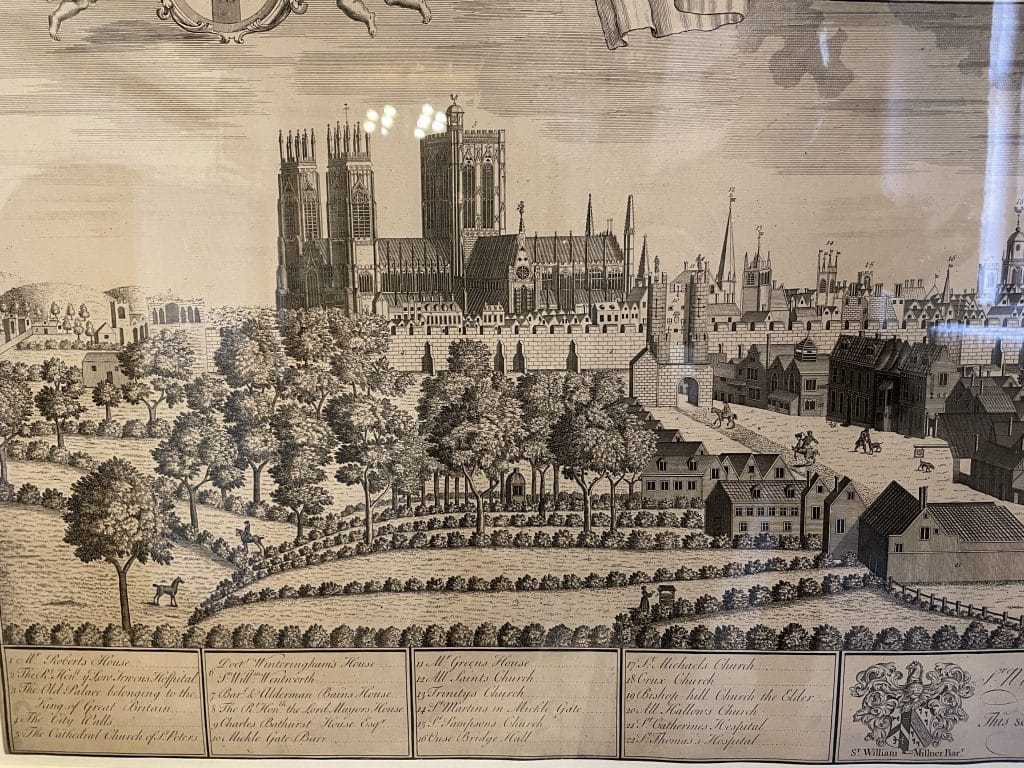

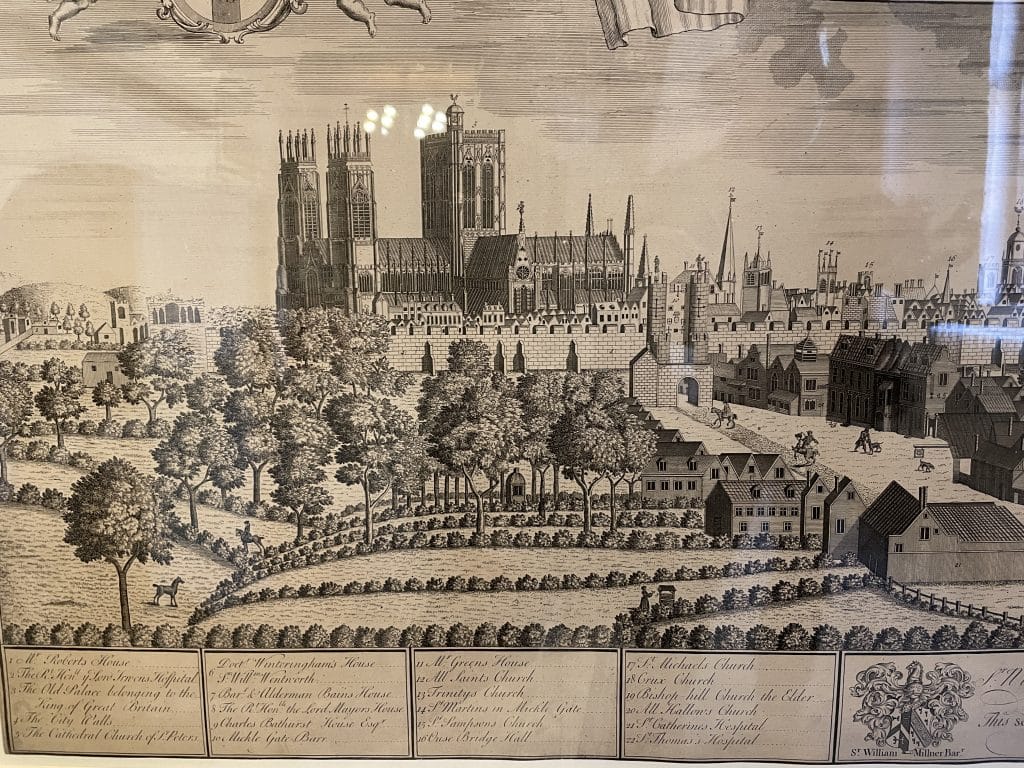

York sat slightly proud upon raised ground, its medieval stone walls encircling the city. Behind these walls the skyline was punctuated by lofty spires of York’s parish churches, many topped with golden weathervanes. However, the ancient Minster church would have stolen the show. It was by far the largest, tallest, and most resplendent building in the city and would have been visible from miles around. Its Norman edifice, including three square towers, one central and two at the west end of the Minster, dominated its surroundings and dazzled the onlooker.

Within half a mile of Micklegate Bar, the wide road narrowed. Open fields gave way to gardens, orchards and a smattering of buildings. At this point, the Herald records that a plethora of religious brethren from the many monasteries, priories and parish churches of the city had come together to greet their new monarch. Alongside them was a ‘marveolous great nombre of men, women and children on foote’. As Henry passed, the crowds cried out “King Henry! King Henry! Our Lorde preserve that swete and welefaverde [well-favoured?] face!” Notoriously supportive of Richard III, the citizens of York clearly hid well any reservations they harboured toward this new, Lancastrian king.

Through the Streets of York…

The Herald’s Memoir allows us to trace, almost precisely, the route Henry VII took from his entry into York at Micklegate Bar to his destination, the Archbishop’s Palace, sited adjacent to York Minster. Let us follow in his footsteps…

Micklegate

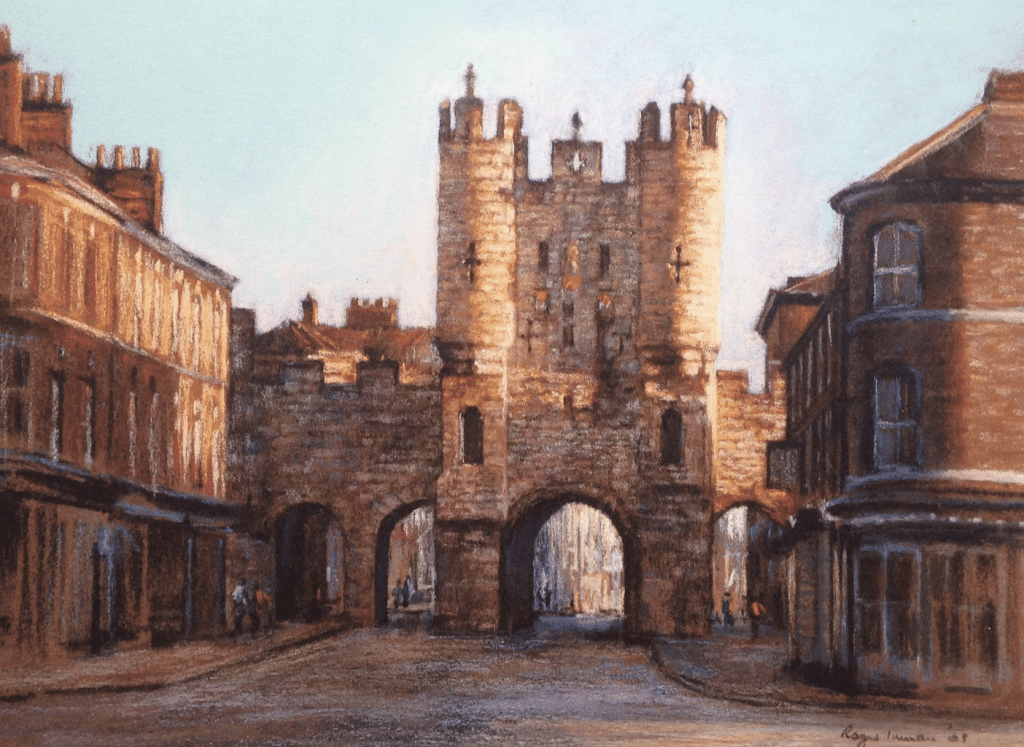

Micklegate Bar was the southern entry point into the city. In 1569, the Earl of Westmoreland had called it the ‘strongest bar with the highest and strongest walls’.

In the fourteenth-century, an early wooden structure had been replaced by a stone one, comprising of a barbican, portcullis, and a heavy wooden door that had a ‘wicket’, or smaller pedestrian door, embedded in it.

Thankfully, we do not have to guess what Micklegate once looked like. We can see it, both on the early eighteenth century etching of the south side of York mentioned above, but also since it still stands today, its two symmetrical, rounded turrets, topped with crenulations and sporting its medieval arrow slits.

It was here that the citizens of York staged the first pageant for Henry. This would be one of three. Elaborate prose, imbued with myth, legend and symbolism, allowed the people of York to show their loyalty and submission to the monarch.

A full transcription of the prose is captured in Emma Cavell’s book, The Herald’s Memoir. I will not repeat it here. Rather, I will summarise the festivities as Henry passed through the city, concentrating on the route taken by England’s first Tudor king.

At Micklegate, ‘dyvers personages and mynstrelsyez [minstrels] took part in the first pageant in which Eboracus, the legendary founder of the City of York, submitted to the new monarch, asked for his blessing to be given to the city and welcoming him to York as its sovereign lord. This is exactly what Henry wanted to hear. He had set out from London to impress upon the north their misplaced loyalty to his predecessors. His intention was to show clemency and be a magnanimous Lord – but only if the people of York and its environs demonstrated their complete submission and acceptance of the new King. This was a good start.

Once within the city’s walls, Micklegate (the street that passed under Micklegate Bar toward the centre of the city) swept in a north-easterly direction to reach the southern bank of the River Ouse.

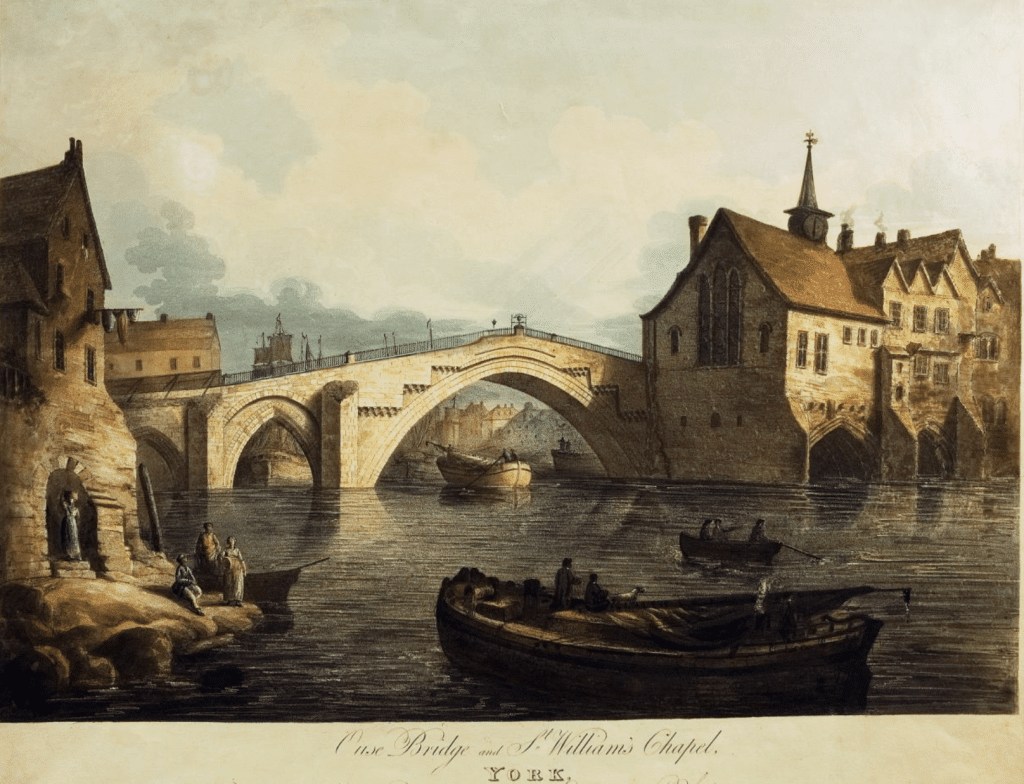

The Ouse Bridge was an ancient river crossing point connecting the city’s east with the west. According to Raine in Medieval York, it is likely that there had been a point of crossing across the river from prehistoric times and that the Romans had built the fort of Eboracum to control this critical, strategic landmark. A stone bridge likely replaced the original wooden one in the early twelfth- century.

At the time of Henry’s visit, the Ouse Bridge had six arches. These rose to a lofty apex at the centre, so the two middle arches allowed water-borne vessels to pass under the bridge. Much like its London equivalent, the bridge was crammed on both sides with shops, tenements, the City’s council chamber, a hospital, two prisons and a chapel called St William’s Chapel. The latter survived until it was dismantled in 1810.

Another rather quaint point of note about the bridge is that it housed a clock which rang across the city twice a day to mark the start and end of the day. According to Raine’s Medieval York, in summer, it chimed at 4 am, in winter at 5 am, and then again at 8 pm each evening. Very useful in a time when only the elite had access to clocks!

Given its significance to the city, it is unsurprising that the second pageant was held at Ouse Bridge – at its ‘hider end’. In his book Henry VIII and the Tudor Pretenders, Nathan Amin states that this was at the near, or southern, side of the bridge. The Herald’s Memoir describes this pageant being ‘garnysshede [garnished] with Shippes and botez [boats] in every side tokening the kings landing at Milford Havyn [Milford Haven]. However, the York Civic Muniments describes a different pageant, comprising a council of six kings, which Amin notes ‘represented the half-dozen previous monarchs who shared a name with Henry’.

King Solomon was the principal protagonist, by legend noted for his wisdom and justice. Through the prose, Solomon entreated the new king to be wise and just and intercede on behalf of the city. Royal favour would be required for the city to prosper. Pressing forth across the Ouse Bridge, it is easy to imagine colourful banners and arras draped from shops and houses that lined the route, with eager onlookers hanging out of upper storey windows to cheer on the new monarch.

Beyond the Ouse bridge, at the junction of Low Ousegate and Spurriergate, the royal cavalcade turned left towards Coney Street, ‘Coney’ being the ancient Viking name for ‘King’. At this junction, a third pageant was staged representing the Assumption of Our Lady, appropriate since on the corner of the intersection of the two streets was the twelfth-century church of St Michael. By legend, St Michael was said to be the principal angel that carried Mary’s soul into heaven.

In the pageant, Mary acknowledged that her son, Jesus Christ, had given Henry the right to govern and protect the people of England. The theme of mercy, bounty, and generosity toward the city continued unabated! Everything was going to plan.

The King then progressed east to west along Coney Street. During the medieval period, this street had been described as the most important in York and once home to the wealthiest Jew in all of England! Hence, we can more easily understand why Coney Street formed the traditional royal route of entry through the city. Galleries had been built above the road, connecting one side of the street with the other. As Henry rode along ‘obles and wafers’ and ‘comfettes’ rained down upon the King like ‘hale stones’ in a medieval version of ticker-tape or confetti. It is easy to imagine the palpable air of excitement as crowds thronged the streets. The city had conveniently swept its once stalwart allegiance to the dead King Richard under the carpet.

At the far end of the street came the final pageant, where ‘King David stode armed and crowned, having a nakede swerde [sword] in his hand. In his speech, David surrenders ‘his sword of victory’ to Henry, acknowledging the King’s prowess in claiming the throne and pledging the City’s allegiance to the new monarch.

The justice, mercy, divine right to govern and power of this new king had been dutifully acknowledged. The citizens of York had fulfilled the royal expectations of gracious acceptance and bountiful praise of the worthiness of the new Tudor dynasty. Given the earlier rumours of a rising in the North, perhaps this show of obedience had begun to settle any notion that rebellion in the area posed a serious threat to Henry’s throne….at least for the time being.

It was time to move on to the Minster for the final act in this colourful theatre of civic pageantry. Turning north at the end of Coney Street, the king rode along Stonegate. Today, this narrow road retains its medieval feel; quaint higgledy-piggledy shops line the street, jostling for space, while the sign for ‘The Old Starre Inne’ straddles the thoroughfare in a nod to York’s medieval roots. It is my favourite street in the city.

Arrival at the Minster and Archbishop’s Palace

At the end of Stonegate, the principal access point to the Minster precinct (also known as ‘Minster Close’) awaited the royal party. Even today, the point of intersection between Stonegate, running north-south, and Petergate, running east-west, feels like the heart of the city – and with good reason. During the Roman occupation of York, this point marked the intersection of the Via Praetoria and the Via Principalis.

By the medieval period, a timber-framed gateway called ‘Minster Gates’ stood at this point, giving the main route of access into the Minster precinct.

According to the detailed study of the Minster Close by Dr Stephania Perring, a first-floor chamber was above the gatehouse. The gateway itself was furnished with two heavy wooden doors that were refitted just three years before Henry’s visit in 1483. According to Dr Perring, ‘The doors were reinforced with four hundred pounds weights and a quarter of “medium iron”,’ suggesting ‘a more defensive look’. Records exist of the work undertaken to create these new doors. It required two carpenters to work for 66.5 days to complete them. It is likely that not only were they substantial but carved with ‘sculpted decoration’ and ‘possibly with the arms of the Liberty of St Peter’. Sadly, the gateway was destroyed in 1800 without any image or plan being noted down, and so we are left with no visual evidence of how Minster Gates looked to Henry that day.

What is clear from The Herald’s Memoir is that the king passed the south side of the cathedral to reach the main west doors, where the Archbishop of York and the Dean of the Minster awaited his arrival.

York Minster

York Minster is a wonder of the medieval age, with deep roots penetrating England’s Anglo-Saxon past. If you were wondering about the difference between a cathedral church and a minster, the latter is a ‘church built during Anglo-Saxon times in Britain and is related to teaching space used by missionaries or connected to a monastery’. York is both a ‘minster’ and a ‘cathedral’.

The first cathedral was founded on the site in 627, with the current minster being of Norman origin. This was the church beheld by Henry VII as he rode up to its west doors on that Spring Day in 1486.

Founded in 1225, York’s current minster would not be entirely complete until circa 1500 and even a king could not fail to be impressed by its Gothic grandeur. If you visit today, I recommend approaching the Minster via Bootham Bar or Duncombe Place to enjoy the most spectacular first glimpse of the west end of the building. I defy you not to stand in awe and say ‘wow’!

It is possible that at this point, Henry dismounted his horse and knelt upon a cushion to kiss the cross offered to him by the archbishop. This seems to have been a part of the royal entry into a city at the time, as my previous co-author and I have seen in later royal progresses (See In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn for Henry VIII’s reception at Gloucester Cathedral). The Archbishop of York at the time was Thomas Rotherham, who had been appointed to the See of York in 1480. Interestingly, he had sided with Elizabeth Woodville following the death of Edward IV and, for his pains, spent around one month in the Tower during the height of the summer of 1483. Two years later, in 1485, he was made Lord Chancellor only to be dismissed in November of that year when Henry VII appointed another cleric to the position, a man who would become one of Henry’s most trusted advisors: John Alcock.

Having been received at the great west doors of the Minster, the Herald’s Memoir states that the King entered the church to offer at the high altar and then at the shrine of St William in the east end of the church before returning to the Dean’s stall. At that point, the records tell us that the Archbishop stood before his throne and sang a Te Deum to celebrate Henry’s coming to the city. All this complete, the King retired to his lodgings in the adjacent Archbishop’s Palace to take stock of the day. Surely, he must have been satisfied.

Following rumours of Sir Francis Lovell’s uprising centred on the Yorkshire cathedral city of Ripon, around 25 miles from York, Henry had dispatched his uncle, Jasper Tudor, by then the Duke of Bedford to deal with the threat. According to Temperley, Jasper has taken around’ ‘8000 lightly armed men’ with him. At Ripon, the Duke offered a general pardon for all those who would lay down their arms. Lovell fled and the rebels dispersed. For now, the immediate threat to Henry had passed and he could enjoy the fine surroundings of the Archbishop’s Palace.

But what do we know of the Archbishop’s Palace, and do we know where Henry lodged during his stay there?

The Archbishop’s Palace at York

The old Archbishop’s Palace occupied the area to the north of the minster. It had been built in 1181 by Archbishop Roger and was already in decline by the time of Henry’s visit. It would be ruinous and abandoned by the end of the sixteenth-century as the Archbishops of York preferred to reside in their country palaces at Cawood and Bishopthorpe, both lying just a few miles outside the city. Thus, the early medieval palace had already fallen from favour by the time the minster was complete.

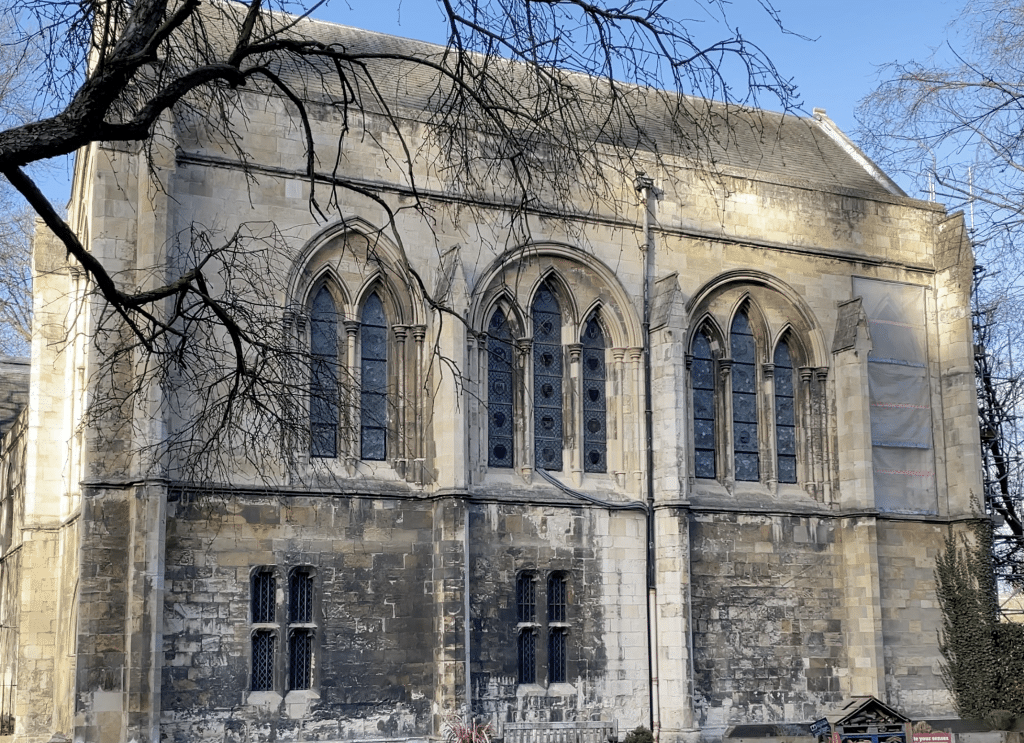

Only fragments of the palace survive today, the main feature being the palace’s chapel, built circa 1230. This now functions as a library and is home to the cathedral archives. There is also a short range of arches in the Romanesque style, which Perring states is ‘perhaps a fragment of Archbishop Roger’s palace’ that lined a walkway leading to the chapel’s west end.

While no floor plan of the palace survives, we do know from other sources that there was a west range, which contained the gatehouse and entrance to the palace precinct, a north range, which contained the chapel and archbishop’s private rooms, as well as a (possibly) stand-alone, aisled great hall, which is very relevant to our story.

It is unclear exactly where this building was sited. Stephania Perring agrees, tentatively labelling the building as such in her precinct plan. In private correspondence with the author, she writes: ‘It was suggested by Thomas Atkinson, architect of York Minster c. 1780, son and grandson of York Minster masons, in a witness statement for a court case. The Great Hall was demolished during the 16th C, and therefore Carter’s drawing of 1790 shows a barn, previously used as the covered tennis court of Ingram’s Mansion. Other scholars prefer to locate the Great Hall next to the chapel, but I think that there was not enough room there for such a large building and I prefer Thomas Atkinson’s explanation. The location is also coherent with what happened in other bishops’ palaces.’

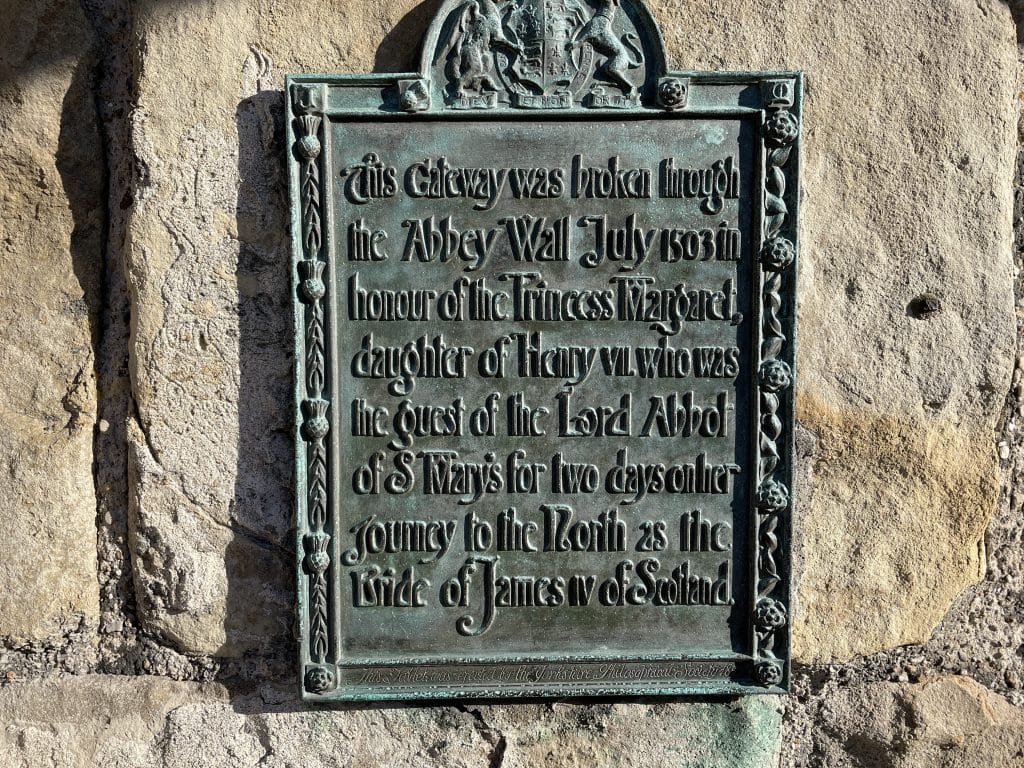

An inventory taken in 1531, after the archbishop’s palace was returned to the See of York by the Crown (following Thomas Wolsey’s fall in 1530), hints at some of the rooms in the palace. Like many inventories, we can only guess the exact layout. However, Perring notes that the inventory refers to the ‘Queen’s rooms’ and surmises that this likely referred to Margaret Tudor, who also passed through York on her way to marry the King of Scots in 1503. These rooms appeared to have been on the first floor of the west, or gatehouse, range, with two chambers being specifically noted as associated with ‘the queen’.

There is often a precedent for using the same lodgings for royal guests on subsequent visits. Does this mean Margaret occupied the rooms her father used during his 1486 progress?

We have already seen that at some abbeys, a suite of rooms was maintained for the royal household, like those at Waltham. Otherwise, the abbot’s lodgings would often be ceded to the King (and Queen). These were the highest status rooms at any abbey. Of course, there was no Abbott at York. However, the archbishops’ rooms would have been the most high-status ones at the palace. The inventory suggests that such an arrangement did not happen in relation to Margaret’s stay in York. Whether we can say the same for Henry’s visit is not certain. Henry lodged in York for just over a week, whereas Margaret stayed for only one night.

It may well be that the first Tudor king occupied the archbishop’s privy lodgings. It is to these lodgings that we now turn our attention.

The Archbishop’s Privy Lodgings at the Palace

The inventory suggests that the archbishop’s private chapel and lodgings were in a north-facing range that ran at right angles to the west range, directly facing the minster and across the main courtyard. As I have already mentioned, the stone-built chapel still stands today. The ground floor was entered via a south-west facing doorway. This building was divided into a lower and upper chapel during the Tudor period. Each served slightly different functions. In the lower chapel, the archbishop would receive those less worthy of a reception in his private chapel on the first floor.

On the upper floor, this private chapel was connected to the archbishop’s private hall and chamber by an entrance room, with a parlour on the ground floor.

The Order of the Garter Convenes in York

The King had arrived in York for the annual St George’s Day celebrations, held on 23 April. Even today, this is known as ‘Garter Day’ and recognises the meeting of the Members of the Order. While St George’s Chapel, Windsor, is the spiritual home of the Order today, during the medieval period, such meetings were almost always held at the Old Palace of Westminster: the seat of royal power and government in England. Emma Cavell notes that it was extraordinary that a meeting of the chapter was held elsewhere, but York was accorded this privilege in 1486.

Henry VII had deliberately choreographed a lavish series of set-piece events designed to impress upon the North the King’s divine right to rule and the acquiescence of England’s nobility, many of whom gathered in York that Spring to participate in the celebrations. The Herald’s Memoir picks up the story on St George’s Eve, when Henry heard Evensong, in public, at the Minster.

While Henry VII is rarely considered an icon of fashion, closer inspections show that the King spent lavishly on the finest materials to adorn the royal person. He knew full well that it was not enough to win the Battle of Bosworth and take a Crown but that he needed to look and act the part to convince the populace that he was worthy of holding onto it. This he did in style at York, wearing a blue velvet over mantel with a ‘cap of maintenance’ upon his head. The latter is a high crowned hat, flattened on the top and edged with ermine at the base. The king wore this again the following day when he took the trouble to be crowned for a second time inside the Minster. If that’s not ramming the message of Henry’s arrival as the rightful, new monarch of England home to the citizens of the North, then I don’t know what is!

Accompanying the St George’s Day celebrations was the usual feasting. This was held in the Archbishop’s Great Hall, whose position I have postulated was in the centre of the palace precinct. The Memoir tells us that the hall was aisled, divided into three by, (one imagines), two rows of columns. Thus, the tables were arranged with two ‘in the middle aisle of the hall’ and two more in both other two aisles, totalling six tables in all.

Amongst those serving the King was John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who was to be invested in the order later that day. He wore his garter robes and, interestingly, later that year would become godfather to the new Prince of Wales, Arthur Tudor. Anthony Browne, Henry’s Standard Bearer at the Battle of Bosworth acted as sewer. Lord Scrope of Bolton Castle served water to the king. He had been a Yorkist who had quickly turned coat to show his allegiance to the new Tudor dynasty. Finally, the Archbishop sat in the place of honour on the King’s right-hand side. Hilariously, the Herald takes the time to mention that ‘at the other end of the kings borde that day satt noman’!

The Herald then mentions who is sitting where in the hall in order of status. This included the abbot of Fountains Abbey and the Abbot of St Mary’s on ‘the furst table in the myddez [middle] of the hall’. As you might imagine, members of the royal household rubbed shoulders with the religious men of the Minster, the Mayor of York, ‘and his bretheren’ along with ‘other citizens in great nombre’. A good time was clearly had by all as attested to twelve months later when William Paston III wrote in a letter, ‘And you need to warn William Gogyne and his fellows to go easy on the wine for now, for everyone says that the town shall be drunk as dry as York when the king was there.’

During the feast the King’s officers at arms ‘cryde his largesse iij [3] times’ saying ‘de treiz haute, treiz puissant, treiz excellent prince, le treiz victorious roy dAngliter et de France, seigeur de Irland et souveraigne de la treiz noble order…’ [Translations: very high, mighty and excellent prince, the very victorious King of England, France and Ireland, and sovereign of the most noble order…]

With the feasting complete, the King returned to the Minster to hear Mass before walking the short distance within the Minster to its Chapter House to hold the Chapter of the Garter and invest its two new members, John de Vere and John Cheney as Knights of the Order.

At this point, the Herald left the progress, and the records fall silent for two weeks until the Herald re-joins the royal party at Worcester on Whitsunday. Therefore, we do not know precisely when Henry left York. However, Emma Cavell states that he was ‘certainly at Nottingham Castle on May 3, when he appointed the Duke of Bedford and the Earls of Lincoln, Oxford, and Derby to enquire into treasons, felonies and conspiracies in Warwickshire and Worcestershire’.

Visitor Information

York is simply a treasure trove of historic buildings, dripping in centuries of engrossing history. The fingerprints of millennia of people are left behind in its layers of history. Like other great medieval cities of England, York is a treasure to be enjoyed, containing far more than any single location. Therefore, if you are planning a visit to this one-time capital of the North, then take your time, for there is plenty to enchant the modern-day time traveller. I highly recommend that you plan at LEAST a two-day stay in the city- three if you prefer to savour your history at a more sedate pace.

York is the capital city of my home county of North Yorkshire. Therefore, it is a city that I know well and heartily recommend. Of course, one could write a whole book about what to see and where to go to enjoy the best of York. So, I will highlight what can be seen in association with this progress and some of my personal recommendations for enjoying the best of historic York.

Parking in and around York is plentiful (including a park and ride). However, the city is a tourist hotspot at all times of the year, particularly so in summer. The authors, therefore, recommend making a point of arriving early. On this occasion, we began our trail around 8 am and were able to visit many of York’s most popular outdoor tourist areas almost undisturbed up until about 9 am. This is a golden hour before many of the indoor attractions open, and the streets rapidly fill with locals and visitors alike.

Following in the Footsteps of Henry VII…

It is entirely possible to retrace Henry’s route as he passed through York from Mickelgate, across the replacement Ouse Bridge, by St Peter’s into Coney Street and finally up Stonegate to reach the Minster. However, do not expect oldey-worldey historic buildings along the entire route. Sadly, modernity has engulfed Coney Street leaving behind a typically uninspiring shopping thoroughfare. However, thankfully, all that changes when you reach Stonegate. Here you can delight in the sight of timber-framed buildings crowding in upon a narrow lane, which leaves you with an altogether more satisfying experience of following in the footsteps of Tudor royalty. The only thing that might crowd out your inner serenity is the hordes of people who are enjoying the same – particularly during summertime and at the height of the day.

At the top end of Stonegate, you will find the intersection with Petergate. Here, once stood the ancient gateway leading into the Minster precinct. Don’t worry! You can’t miss it; a tantalising glimpse of the Minster directly ahead of you will set you all a-tingle with mounting anticipation.

York Minster

It is almost unthinkable not to visit the Minster on any visit to York. I have been inside many times, and it draws me back repeatedly. Of course, as we have heard, the Minster and the Archbishop’s Palace were the epicentres of Henry’s stay in the city. And so, just like Henry, you should take your time to savour all its delights.

York Minster remains the largest Gothic cathedral in Northern Europe. There is a considerable entrance fee, but it is, in our opinion, worth it. Wandering up the nave to the heart of the church will set you in the erstwhile King’s footsteps, not forgetting to visit the intact chapter house (one of the finest in England in my opinion) where the Garter Day celebrations of 1486 were held. Before you leave the Minster, you might want to seek out the tomb of Henry’s Archbishop, Thomas Rotherham, who died of the plague at Cawood Castle in 1500.

Immediately to the north of the Minster is Dean’s Park, once the site of the Archbishop’s Palace. As you cross in front of the Minster’s west doors to the park, where the metal railings and gate are sited, you will be walking towards where the western entrance range to the palace and its principal gateway once stood. Beyond these railings, roughly defined by the grassy area you see before you, was once the precinct of the palace with its large, central courtyard.

You will want to meander along the path in front of you, passing the stone arches mentioned in the above entry, and then keeping on until you see an unmistakably medieval building directly in front of you. This was once the Archbishop’s private chapel and, as mentioned above, it now serves as the Cathedral’s library. On the wall next to its west doors is a blue plaque commemorating the fact that Richard III had his only son, Edward of Middleham, invested as Prince of Wales in the chapel. It is poignant to think of such dreams so tragically shattered, first by Edward’s premature death, then Anne Neville’s and finally, of course, Richard himself – and all within a few short years.

Pre-COVID, it used to be possible to book an appointment to view books in the Cathedral’s library (which includes a copy of one of Katherine of Aragon’s prayer books BTW). Doing so a few years ago allowed me a glimpse inside the old chapel which was stuffed full of bookshelves and books, as far as I can remember. Sadly, at the time of writing this, no access to the library is allowed.

Many people sit awhile on the grass and enjoy a picnic on a fine day. You might want to do the same.

Finally, in this section, York is one of the few remaining cities in England with its medieval walls and gates largely intact. You can walk around them and explore the various gates; Walmgate Bar has a quaint Tudor coffee house over its central arch; the Richard III experience at Monk Bar; the Henry VII Experience at Micklegate Bar (both a bit touristy and basic for my liking!). For the best views of the Minster, head to Monk Bar and walk in an anti-clockwise direction.

Other Tudor Locations of Interest

Of course, Henry VII was not the only Tudor to visit York. His son would do so under similar circumstances following unrest in the north that was inflamed by the religious changes sweeping across England. This became known as The Pilgrimage of Grace. This visit is covered in full in In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII as Catherine Howard was at Henry’s side during this momentous progress. I will not cover the background, nor the details, of that visit here.

However, I will mention that the main locations associated with this visit are The King’s Manor and the ruined Abbey of St Mary, now the Museum Gardens. The King’s Manor is now the Centre for Medieval Studies and is part of The University of York. This, alongside some of the buildings associated with the dissolved abbey, became the royal lodgings for the entirety of Henry VIII’s visit to York. While you are in the Museum Gardens, I urge you to time your visit with the opening times of the Yorkshire Museum for it houses The Middleham Jewel, thought to be from the Wars of the Roses period and found by a metal detectorist close to Richard III’s childhood home of Middleham Castle. It is exquisite!

As you explore York, you will come across narrow, medieval streets and ‘snickleways’ (a local name for ‘passageway’) that lead you in different directions; shops filled with a cornucopia of delights to fascinate and tempt the passer-by. Furthermore, there are so many ancient churches, landmarks and museums to see, and we defy you to pass them by and reach your intended destination without making several fascinating diversions!

If you would like a little more inspiration on other places of medieval and Tudor interest not associated with the 1486 progress, then I invite you to check out my short video: The Top Five Tudor Places to Visit in York.

THIS COMPLETES THE NORTHERN LEG OF HENRY VII’S 1486 PROGRESS TO THE NORTH. Congratulations, you made it! Now let me know what you enjoyed most by emailing me at sarah@thetudortravelguide.com. I’d love to hear from you!

Sources and Further Reading

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543, by John Leland.

Henry VIII and the Tudor Pretenders: Simnel, Warbeck and Warwick, by Nathan Amin. Amberley Publishing. 2020

In the Footsteps of Anne Boleyn, by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger. Amberley Publishing. 2013.

In the Footsteps of the Six Wives of Henry VIII, by Sarah Morris and Natalie Grueninger. Amberley Publishing. 2015.

Medieval York: A Topographical Survey Based on Original Sources, by Angelo Raine. John Murray, London. 1955.

The Cathedral Landscape of York: The Minster Close c. 1500-1642. Volumes 1 & 2, by Stefania Merlo Perring. Unpublished PhD. Thesis. September 2021.

The Herald’s Memoir 1486-1490: Court, Ceremony and Royal Progress. Edited by Emma Cavell. 2009.

York Palace; a Vanished Jacobean Mansion, by R.M. Butler. 1988. York Architectural and York Archaeological Society. Volume 8, pages

JORVIK https://www.jorvik.co.uk/york-city-walls/