Luscious Tudor Pears In Conserve

Many of you will have been as sad as I was to learn that, here in the UK, we have just lost one of our most ancient pear trees to a new railway project. In honour of this tree, and as pears are currently seasonal and easy to obtain, I have chosen the pear as our main ingredient for this month’s Tudor food blog.

Although the pear has never been as popular as the apple, these long-lived trees have a long history in England. Probably not indigenous, the wild pear arrived on our shores in Saxon times – and most probably even earlier than that. The Saxons called the fruit the “pere” or “peru hu”. This was probably the ancestor of the domesticated pear, which were introduced to many parts of Europe by the Romans and later, during the medieval period, by monks (in England by the Cistercians, in particular). On several occasions, the Domesday Book of 1086 mentions old pear trees being used as boundary markers.

There have been a variety of domesticated pears since the Romans, but identification can be tricky as names changed all the time. England’s best known and still available early pear is the WARDEN, which was first mentioned by the English poet and theologian, Alexander Neckam, in the thirteenth century. A warden is basically a firm-textured cooking pear that keeps well over the winter, a property highly appreciated in times when food preservation was limited.

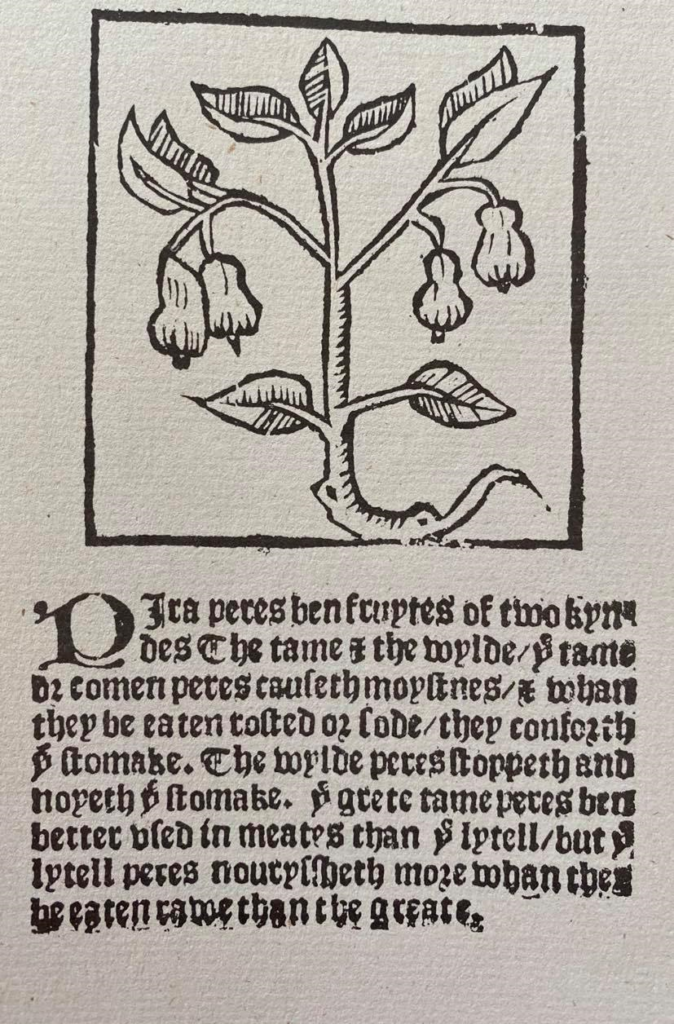

In 1530, Cardinal Wolsey is reputed to have been eating roasted wardens at Sheffield Manor at the moment when he was first seized with his fatal illness. One of the earliest entries relating to the pear in an English herbal can be admired in ‘The Grete Herball‘ which was published by Peter Treveris in 1526.

Harris, a fruiterer to Henry VIII, introduced pears from France and the low countries in 1533 for the orchard at Teynham (Kent). In 1548, William Turner lists the wild pear and its various names. He also mentions a revival of interest in orchard management as part of his Herbal of 1568.

In 1580, Harrison said that “pirrie’ (pear cider) was made from pears in Sussex, Kent and Worcestershire. The pear’s importance was recognized by the incorporation in Worcester’s city arms. The image below shows the three pears sable, included in the coat of arms of the city on the direction of Queen Elizabeth I, when she visited Worcester in 1575.

The Elizabethan herbalist, John Gerard, showed in his Herbal of 1597, that the number of pear varieties had increased since the beginning of the century. He illustrated eight pears: the Jenneting; the Pear Royall; the Quince Pear; the Katherine; the Saint James; the Burgomet; the Bishops and the Winter Pear. He lists several wild hedge pears and states that they taste too harsh and bitter for consumption and should be used instead for making ‘perry’ cider.

William Shakespeare does not appear to have enjoyed pears, as most of his references to them are not favourable.

‘…… as crest-fallen as a dried pear (Merry Wives of Windsor)

……I must have saffron to colour the warden pies (Winter’s Tale)

…. Your old virginity, is like one of our French withered pears’ (from “All’s Well that Ends Well”).

Pears came in different sizes, tastes, textures and colours. In his Five Hundreth Pointes of Good Husbandrie (1573), English poet and farmer, Thomas Tusser, is one of the first to mention the different colours. General storage advice was given in the Second Book, Entreating the Ordering of Orchards (1577) by Conrad Heresbach. The pears should be stored in sand, flocks (scraps of wool), covered with wheat or chaff, or by dipping the stalks in boiling pitch and then hanging the pears up. Keeping the pears in freshly boiled wine was another option.

The earliest record of a garden design incorporating an orchard of Warden trees dates to the late sixteenth-century. it was commissioned by devout Catholic, Sir Thomas Tresham, at his lodge at Lyveden in Northamptonshire. Lawson’s New Orchard and Garden (1597), advised that “hard winter fruit and wardens” were not fit to be gathered until Michaelmas (29 September).

Pears were a popular gift to the nobility by commoners, as recorded on the 15 December 1534, when Thomas Cromwell received Wardens from Sir Henry Penago. On 2 April 1539, the accounts show an entry of 12d given to a poor woman for bringing Wardens. Tudors were not yet convinced that eating pears raw was a good thing, due to their ‘cold and wet’ properties, but they did recognize their health benefits eaten cooked with the addition of sugar and spices. Boiled with honey in wine made them ‘agreeable and wholesome’.

Pears are often depicted in Renaissance religious paintings and frequently feature in Flemish flower and fruit paintings of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries. The pear gives rise to metaphor – mostly sexual in nature – and invited comparison to the shape of the womb.

The health benefits of the (cooked) pear and Wardens were acknowledged by the Tudor physician, Andrew Boorde, who said in his Dyetary of Health, published in 1542, that they were nutritious roasted, stewed or baked and comforted the stomach – especially if enjoyed eaten with other preserved fruits. A view shared by Christopher Langton in his Introduction to Physicke (1545); William Bullein in his Book of Simples (1562) and Thomas Cogan’s The Haven of Health (1584). John Harrington’s message of 1607 is clear, ‘Raw pears a poison, baked a medicine’.

And, on that note, we will follow their advice and make full use of this delicious fine fruit and prepare a dish which frequently featured at the tables of the nobility as part of their banquet. This recipe is also so easy to replicate you can’t go wrong. The aroma and taste are divine and will not disappoint even the fussiest eater.

RECIPE

To make Wardens in Conserve from A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye, a recipe collection gathered by Matthew Parker, Master of Corpus Christi College in Cambridge, published in 1545/57/75.

This recipe is one of a variety that existed for this pear based ‘sweetmeat’. The earliest we know of in England dates to 1390, under the name of ‘Peers in Confyt’. It is believed that at Henry IV’s wedding feast in 1403, pears in syrup were served together with venison, quails and sturgeon.

Modernised version:

Ingredients:

Hard pears – one per person

Red sweet wine (for Romney, which was a Greek wine popular between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries) – around 250 to 500ml for 4 pears

Clear honey – 100-200ml

Sugar (quite a lot)

Cinnamon (to taste)

Ginger (to taste)

METHOD:

- Boil the wine with the honey.

- Wash and peel pears but do not remove the stalk or cut the pears.

- Place the pears into the wine, cover and allow them to simmer gently until soft (around 20-40 minutes).

- Mix in the spices and sugar and stir over a low heat to dissolve then allow it to boil up for a few minutes to produce a ‘syrup’ type consistency. Add more sugar for thickness, if required.

- Turn and check frequently.

- Remove the pears from the wine, place in dishes and cover with the syrup.

- Serve hot or cold. Decorate with borage flowers, rose petals or cinnamon and then enjoy your posh banqueting dessert – fit for a Tudor king or queen!

Video of How to Make Tudor Pears in Conserve…

If you wish to listen to Brigitte talking about pears in Tudor times and watch her making the ‘Pears in Conserve’ recipe, click on the image below.

Thomas Dawson’s recipe alternative: (1597)

You may also bake the pears without liquid in a dish in the oven. Then remove, allow to cool slightly and peel. Use juice created during the baking process to create a syrup with sugar, cinnamon, cloves, ginger and some wine. Note: Pears were advised to be reserved until after the main meal, to ‘ease the stomach’ acting as a digestif.

Sources used and recommended for further reading:

- Cultivated Fruits of Britain: Their Origin and History, by F.A. Roach

- The Herball, by John Gerard, 1597

- The Grete Herball, by Peter Treveris, 1526

- The Names of Herbes, by William Turner, 1548

- The Booke of Simples, by W. Bullein, 1562

- The Haven of Helth, by T. Cogan, 1584

- Four Bookes of Husbandry, by C. Heresbach, 1577

- The Englishman’s’ Doctor, by J. Harrington, 1607

- Five Hundred Points of Husbandry, by T. Tusser, 1573/1812

- Food and Health in Early Modern Europe by David Gentilcore

- A Proper Newe Booke of Cokerye, 1545/57/75

- The Original Warden Pear by Margaret Roberts

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.

Each month, our Tudor recipe is contributed by Brigitte Webster. Brigitte runs the ‘Tudor and 17th Century Experience‘. She turned her passion for early English history into a business and opened a living history guesthouse, where people step back in time and totally immerse themselves in Tudor history by sleeping in Tudor beds, eating and drinking authentic, Tudor recipes. She also provides her guests with Tudor entertainment. She loves re-creating Tudor food and gardens and researching Tudor furniture.