The 1502 Progress: Troy House, Monmouth, Monmouthshire

Itm the same day to John Staunton for money by him paid to a man that guyded [guided] the Quene from Flexley Abbey to Troye besides Monmouth.

Troy House: The Essential Facts

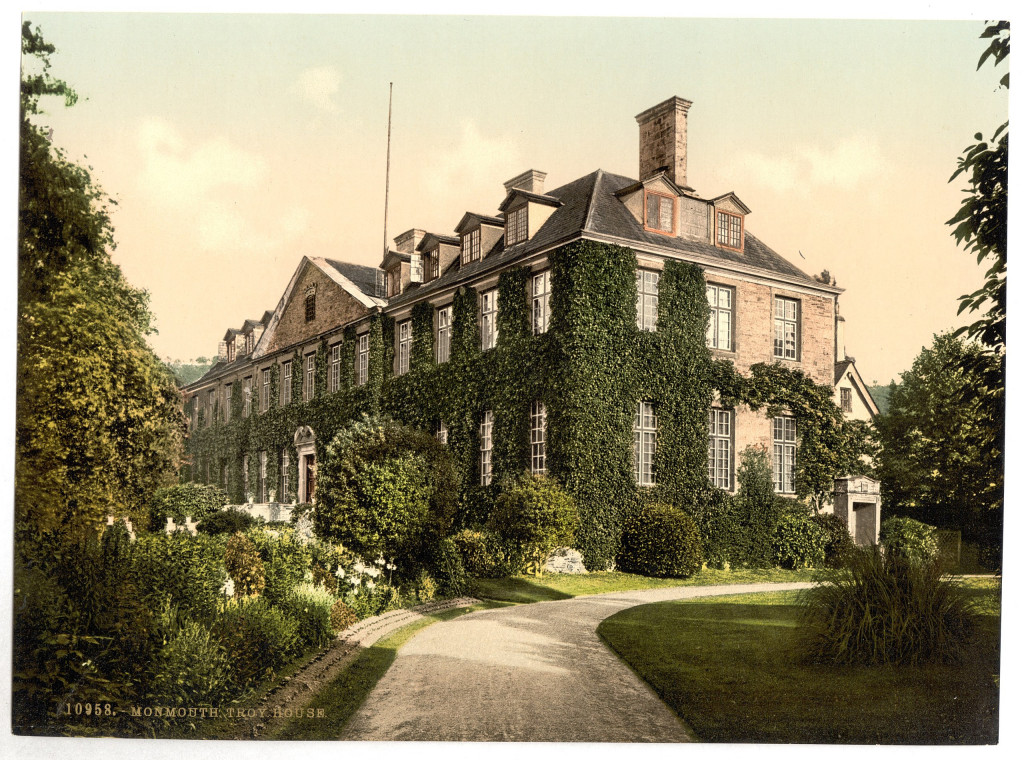

– A medieval manor house that was extensively remodelled in the Georgian period.

– It was visited by Elizabeth of York and Henry VII on the 1502 progress.

– At that time, it was the ancestral home of Sir Walter Herbert, the illegitimate son of Sir William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke and Edward IV’s ‘Master Lock’.

– The Tudor monarchs spent five days at Troy House.

– Elizabeth of York visited the Monmouth Priory during that time and gifted at least two surviving chasubles.

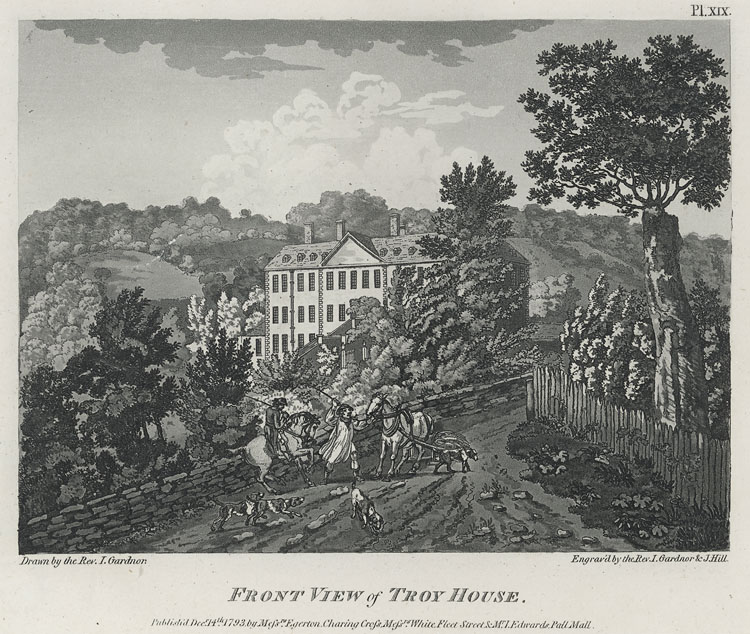

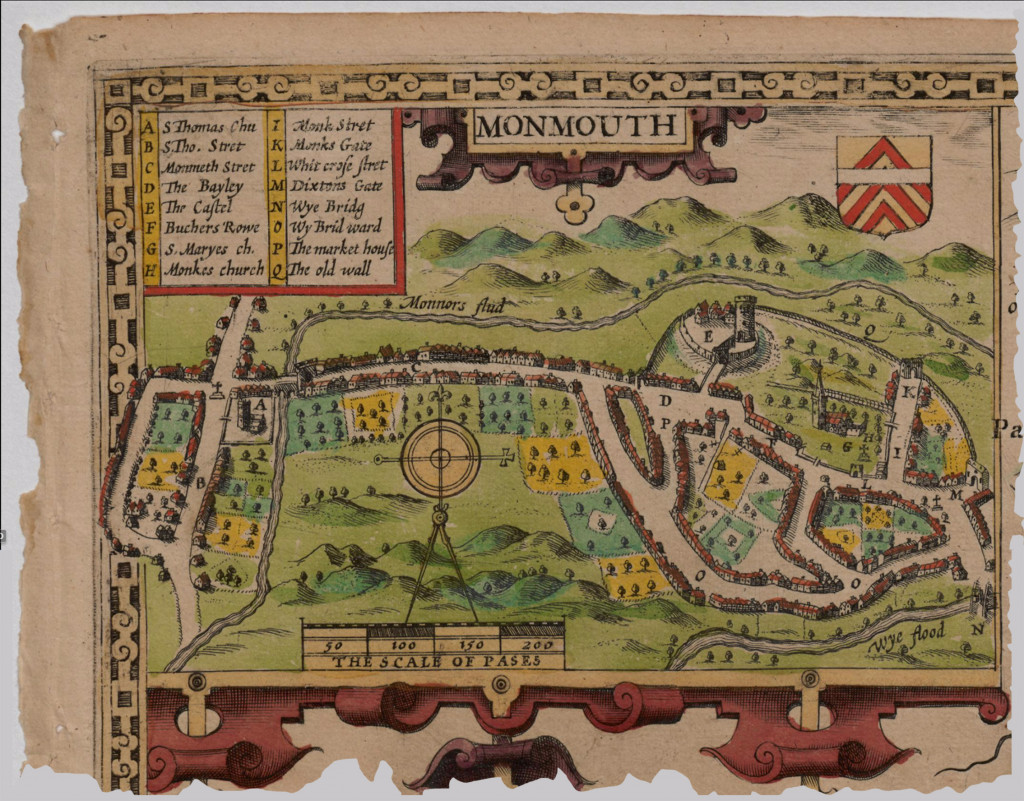

Having stayed at Flaxley Abbey overnight, the following day, on the 14 August, the royal cavalcade was on the move again. Troy House was 15 miles southwest of Flaxley, just a few miles over the Welsh border. The medieval manor house belonged to the powerful Herbert family. It sat in a wide, shallow valley, close to the small village of Mitchel Troy and overlooking the town of Monmouth, which lay just one mile to the north. Here, a twelfth-century castle, in which Henry V had been born in 1386, dominated a strategically important convergence of two rivers: the River Monnow and the River Wye.

These were the Welsh Marches, a notoriously lawless border area between England and Wales. It was ruled over on behalf of the monarch by the powerful Marcher Lords, and there could be none more powerful than the Herbert dynasty. William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, had once been called Edward IV’s ‘master lock’ because of the influence and might he wielded in the region.

Indeed, this William Herbert helped vanquish Jasper Tudor from Wales for the first time in 1461. As a result, King Edward IV gave William Tudor’s title of ‘Earl of Pembroke’ and entrusted him with the care of the four-year-old Henry Tudor, who had been found at Pembroke Castle following Jasper’s flight from his Yorkist aggressors. Little Henry was subsequently raised alongside the Earl’s children at Raglan Castle, the Herbert family’s ancestral seat. Henry would call the place ‘home’ for eight years until William Herbert’s execution following the Battle of Edgcote in 1469.

Arrival at Troy House

To reach Troy House, Elizabeth and Henry must have passed right through the heart of the majestic forest of Dean. That some knowledge of the area was required for safe passage is hinted at in the Queen’s Chamber accounts. The quote at the top of this entry speaks of a ‘man that guided’ [guided] the queen through the forest. It is not hard to imagine the many tracks crisscrossing from Flaxley to Troy, with wealthy travellers relying on locals to navigate its leafy glades.

Hendrick Danckerts (1625–1680)

Nelson Museum and Local History Centre

A map of 1712 shows the topography of the land immediately around Troy House with its woodlands, orchards, meadows and gardens, a water mill, nearby rivers, and roads leading to and from Monmouth, Chepstow and Mitchel Troy. Alongside this land, to the east of the house, was a 200-acre park stocked with deer and other game. The park provided a pleasant pastime for the Tudor nobility, who would have hunted and hawked there – as well as being a bountiful source of food for the table.

The layout of the land in this map is marked with numbers and accords with an inventory of the estate taken in 1557. Thus, it seems little of the house’s surroundings had changed in nearly 200 years, and therefore, we might imagine a similar scene greeting the King and Queen as they approached Troy House on the 1502 progress.

At this point, I want to acknowledge that the primary source of information about the Tudor house at Mitchel Troy comes from the sterling work done by Ann Benson, who has thoroughly researched its social and architectural history. Her book Troy House: A Tudor House Through Time summarises this. Surveys of the extant building, its topography, early maps, and documents, including the little-known but invaluable 1557 inventory mentioned above, shed considerable light on the house that was prepared to receive its royal visitors.

Before we come to that inventory, though, let me take a moment to introduce you to the hosts of this five-day visit. The Lord of the Manor at the time was Sir William Herbert. He was the illegitimate son of the aforementioned William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, and half-brother of the then-owner of Raglan Castle, Sir Walter Herbert.

The latter had fought alongside Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth, and the pair appear to have remained close. Sir Walter remained a loyal servant to Henry, his erstwhile schoolroom companion. Every year following Henry’s accession, Walter sent the King a gift on the battle’s anniversary – a nice touch!

The chatelaine of Troy House at the time is not entirely clear. Still, Ann Benson states that it was probably Sir William’s second wife, Blanche, based on the fact that Henry VII’s visit to Troy is noted in Blanche’s funeral eulogy. Interestingly, after Sir William died in 1524, Lady Herbert of Troy would go on to serve in the Royal household as ‘Lady Mistress’, taking a role in the care of the future Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Sadly, there have been many extensive alterations to Troy House over the centuries as it was passed down from owner to owner. By the twentieth century, it had fallen into dangerous disrepair. As a result, much of the original medieval house has been lost, and its current facade is unmistakably of Georgian proportions. However, enough information survives to give us some idea of the original house’s arrangement and the lodgings provided for the King and Queen.

The Appearance of the Tudor Manor House

Ann Benson postulates that the house’s main entrance is not what we see today. The present house was fashioned from a medieval manor house updated for the 1st Duke of Beaufort, the owner of Troy House in the eighteenth century. A double flight of steps leads to the main entrance on its north side. However, the original entrance was along a long, straight drive leading up from the Trellech/Chepstow road from the west, which entered a courtyard to the south of the current house via a stone archway. This unmistakably medieval pointed archway was demolished at some point in the twentieth century (post-1930).

Today, that first courtyard is surrounded by farm buildings that speak most clearly of Troy House’s medieval past. However, in the sixteenth century, Benson described this as the first, or base, court encircled by service buildings that catered for the needs of the main house and the point where visitors like Henry and Elizabeth would have dismounted from their horses.

A second extant gateway still leads into the smaller inner reception courtyard. Benson suggests that this second courtyard probably had ‘geometric areas of grass and topiary [which] served as a more aesthetically pleasing, formal entrance to the house’. The main entrance to the ‘hawle’ [hall] was through a ‘stone pillared entrance’ in a range that occupied the north side of the courtyard. From the 1557 inventory, it is clear this ‘hawle’ must have been the Great Hall, as we would expect. However, detail from the inventory allows us a delicious peek inside…

Fifty-nine glaives (a ‘glaive’ being a long pole with a single blade) were in the hall, along with eighty pikes and the same number of gads (otherwise known as spears). The collection of armoury harks back to the days when noblemen and landed gentry was expected to muster troops to come to the aid of the Crown, should it be required. Also of notable value were a pair of andirons for the fire, hangings covering the walls and a cupboard, no doubt for displaying valuable plate.

The current house is ‘T’ shaped, with the modern house forming the crossbar of the ‘T’, with the south wing being the stem. It is this latter structure which most notably speaks of the medieval origins of the house. The remaining architectural clues suggest that this south wing was once a hall of two storeys in height (i.e. like those dimensions that we would expect to see in a Great Hall).

However, what is particularly exciting for those of us pursuing the 1502 progress is the mention of a set of chambers whose exact location in the house cannot be determined. Nevertheless, the memory of the royal visit endures through the names of five rooms listed in the inventory. This includes ‘the king’s little chamber’, ‘the king’s inner chamber’ and ‘the king’s great chamber’, while we also hear of ‘the queen’s little’ and ‘great’ chambers.

Despite 50 years having elapsed between the royal visit and the taking of the 1557 inventory, Ann Benson believes that ‘given the stasis in Troy’s development following the death of Sir William Herbert of Troy in 1524, the inventory shows what most likely remains of those items some fifty-five years after the visit’.

The inventory certainly provides a glimpse of the luxury that awaited Elizabeth and Henry at Troy and provides insight into some of the chambers that comprised this largely lost Tudor house. I will link to Ann’s full article in the sources section below, should you wish to read the entire account for yourself. However, here, I will shed light on some of the highlights.

Focusing on the King’s side, the colour scheme was red and green by all accounts, with the windows in the ‘little chamber’ hanging with ‘curtains of green and red silk’. In contrast, the (adjoining) inner chamber contained a bed with a green silk canopy, while the walls were also hung about with red and green silk.

Both rooms are listed as containing beds. Other valuable items included covers, bolster, pillows, tapestries, cupboards, carpets, stools and andirons for a fireplace. Another bed, a ‘Standyng bedd’, could be found in the Great Chamber. Ann Benson suggests that this was likely a bed with hangings able to conceal a low or truckle bed beneath it. This was covered by a silk canopy, fringed in silk, and probably coloured to match the bed’s green silk curtains.

In addition, two long cushions are described in association with a window. This implies some kind of recessed bay window with a window seat. There was a hearth with andirons, ‘old rich’ tapestries covered the walls, while the space was illuminated by one or possibly two windows. Indeed, one was listed as being a ‘grete Wyndowe’, ‘signifying the importance of this room’.

From what we know of Tudor lodgings, these chambers were likely connected, flowing from the larger outer ‘Grete’ Chamber to the smaller inner chamber. I surmise that the Great Chamber functioned like a Presence Chamber and was a public space for reception and dining. At the same time, Henry’s little chamber may have acted as the usual privy chamber and the ‘inner’ chamber as a bedchamber and/or closet.

While it might sound confusing to have a bed in a public chamber, I have come across this in other accounts, where the ‘great bed’ is symbolic of royal power and status (beds, of course, being costly items of furniture at the time) and found in Staterooms, such as a presence chamber. The smaller, more intimate and practical chambers were often used to sleep in. Of course, other rooms may have been allocated to the King at Troy House, but three rooms in a building that was not a standing royal abode or palace would have been perfectly acceptable.

As mentioned, Elizabeth of York had two rooms allocated to her according to this inventory: a little (lytle’) and a great chamber. Just as with the King’s chambers, they were sumptuously decorated. In the Great Chamber was a ‘standyng bedd’ with accessories, including a feather bolster, two blankets and a cover. The hangings were of green silk, with the canopy fringed with silk of the same. No tapestries are listed, but a small chest is recorded as being covered with a red cloth.

In (presumably) the adjoining ‘little’ chamber was another trussing bed with a feather mattress and accoutrements. This time, the colour scheme was russet and blue, with the canopy and hanging once again made from silk, the former decorated with satin braids. Also noted were a cupboard, two stools and a chest or coffer.

Notably, there also seems to have been a closet. A closet was usually the smallest chamber in the sequence of privy rooms. It was used for private conversations, reading, writing or prayer. I have often seen closets lined with oak panelling. In this instance, the closet, which Ann Benson described as being ‘partitioned off from the rest of the chamber’, was hung not with tapestries but simple, painted cloth hangings. She notes, ‘These were likely to be lengths of linen painted a particular colour; they often contained images, including those of a religious nature’.

Now we have explored the house, or what we know of it, we can turn and look at how the King and Queen spent their time while staying at Troy House. First, it is worth noting that this was the single most prolonged stay in any one location since the royal party had left the Old Manor of Langley. By this time, Elizabeth was four months pregnant and was perhaps grateful for the opportunity to rest for a few days, having finally arrived in Wales.

Image via Wikimedia Commons by Philbly Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Looking at the Queen’s accounts, it seems that gifts of food, notably ‘bukkes’ (bucks=venison), were the order of the day. A gift was made to ‘the officers and kepers of the Quenes stable with a buk in reward at Monmouth’, while payment was made by way of reward for deer gifted to the Queen from the Keepers of the Park at Miserden and Brymesfeld [Brimpsfield]. Money was also paid in thanks to ‘a woman that brought a present of cakys and pearys to the Quene’.

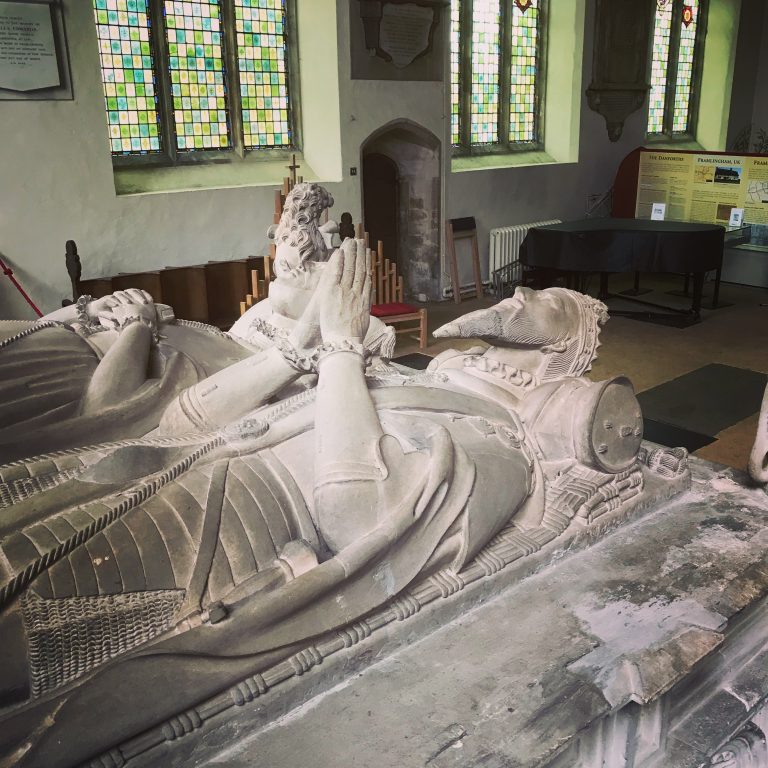

However, this visit’s most fascinating and enduring relics are two (possibly three) chasubles, all dated to 1502, and all surviving intact. A chasuble is a religious overgarment worn by priests during the saying of High Mass. It is often made of rich fabrics and ornately embroidered, often with costly gold or silver thread. It is believed that Elizabeth of York gave one (or possibly two) of these to the nearby priory in Monmouth while she was staying at Troy. A third was gifted to the priory at Abervagenny, possibly while staying at Troy or maybe once the royal party had moved to their next stop: Raglan Castle.

As we have already seen, offerings at religious houses were commonplace for Elizabeth during this progress. There is a suggestion that the Queen visited Monmouth Priory in person to make an offering at the high altar there. This is certainly possible since the monastery lay in the heart of the town, adjacent to Monmouth Castle and overlooking the River Monnow, just over a mile away from Troy House.

The priory was a Benedictine monastery founded in 1080. It was notable because of its association with the celebrated Geoffrey of Monmouth, who may have served at the priory for a time. He was one of the significant figures in the development of British historiography. He was primarily responsible for making the tales of King Arthur famous, much beloved by the early Tudor propagandists.

Amazingly, the prior’s lodging still survives. Although it has been much remodelled and developed over the intervening centuries, its medieval architecture is evident, particularly in the ornate fifteenth-century oriel first-floor window which overlooks the river. This is commonly known as ‘Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Window’.

But what of the chasubles? Ann Benson states that the first ‘was a red chasuble with opus Anglicanum (fine English) embroidery, which is still in the possession of St Mary’s Catholic Church in Monmouth. The other was a red and gold embroidered cope that is now displayed within the church of St Bridget, Skenfrith on the Monmouthshire/ Herefordshire border’.

There is some debate about the provenance of this second item and its connection with Elizabeth, while the association of the former with the royal couple is more clear. It contains the rebus of John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury. Morton was a cardinal and statesman and one of Henry VII’s principal advisers. His death in 1500 was one of the devastating losses experienced by Henry following the turn of the sixteenth century. As Benson suggests, ‘perhaps this explains why Elizabeth – or Henry – was able to donate this particular chasuble to Monmouth Priory during this visit’.

After five days of enjoying Sir William’s hospitality, Elizabeth and Henry moved deeper into Welsh territory. Henry Tudor was coming home. He had not set foot in Wales since he had led an army from the Pembrokeshire coast to the field of Bosworth, where he had taken the Crown to establish a new dynasty. Their destination, and the apex of the progress, lay just 10 miles away at the mighty Raglan Castle.

THE NEXT STOP ON YOUR PROGRESS IS RAGLAN CASTLE, MONMOUTHSHIRE: : Click HERE to continue your journey…

Visitor Information

Troy House is in private hands and cannot be visited. I will be journeying to the area shortly to see what is and is not accessible. I will report back after my visit and amend this section as necessary.

Currently, my understanding is that St Mary’s Church is a functioning Roman Catholic Church in Monmouth and can be visited, as can St Bridget’s Church, Skenfrith, where the Skenfrith Cope is displayed, similarly, for Our Lady and St Michael, Abergavenny. However, I have not had confirmation that the chasubles at St Mary’s and Our Lady are on display. Again, I am waiting for further information to be made available.

Monmouth Priory is an events centre; the exterior can always be accessed. However, because many events are being held during the day, it would be best to contact the venue before any visit if you want to see inside.

The scant ruins of Monmouth Castle can be accessed at all reasonable times. Accessing the site, which comprises a ruined tower and part of a great hall/chamber is free.

For Rest and Refreshment: Plenty of cafes and eateries are available in Monmouth town.

Transport: A car is highly recommended for this location. It is possible to take a train from Gloucester to Chepstow and then a bus to Monmouth. But as ever, the best way to check out possible routes depending on your starting point is the website, ‘Rome2Rio‘.

Other Nearby Tudor Locations of Interest:

Raglan Castle (10 miles): You may want to continue in the footsteps of Elizabeth of York and Henry VII and visit the pinnacle of the 1502 progress, Raglan Castle, once the childhood home of Henry VII. I shall be writing in detail about Raglan Castle in the next entry. However, in the meantime, if you want to watch my video about the Tudor history of Raglan, you can do so here. To learn more about the opening times, check out the castle’s website here.

Chepstow Castle (15 Miles): Chepstow is another location on the 1502 progress. This mighty medieval fortress is a fascinating castle, both historically and architecturally. During the Tudor period, it was owned by the Earls of Worcester, with Elizabeth Browne, Countess of Worcester (the woman whose words were first used against Anne Boleyn to ignite the destruction of the Boleyn faction), is buried in the nearby parish church. Just be sure to check it is open before you visit! I will write more about this location in a subsequent entry.

Tintern Abbey (8.6 Miles): If you love wandering among abbey ruins, nearby Tintern, nestled in the glorious Wye Valley, will be just the ticket. As any medieval abbey, it was slighted following its Dissolution in 1539 and, therefore, is inextricably linked to the seismic religious changes that shook England to its core in the 1530s. You can check out the Cadw website here to learn more about visiting Tintern Abbey.

Sources

Troy House: A Tudor Estate Across Time, by Ann Benson

The Troy House Estate Inventory of 1557: Wealth, Power and Echoes of a Royal Visit, by Ann Benson. p 75. The Monmouthshire Antiquary: Proceedings of the Monmouthshire Antiquarian Association. Volume XXXIV. p 75-92.

Monmouth Priory Website.

2 Comments