The Rolls: Thomas Cromwell’s London Office

The World of Thomas Cromwell is part of an ongoing project here at The Tudor Travel Guide to research and write about each of Lord Cromwell’s principal properties. So far, I have detailed the stories of Austin Friars in the City of London, Great Place in Stepney, Launde Abbey in Leicestershire (podcast and show notes) and Mortlake Manor. The latter was Cromwell’s palatial manor house adjacent to the Thames, conveniently positioned just two miles from one of the ‘great houses’ of Henry VIII’s reign: Richmond Palace.

If you are encountering this project for the first time, I recommend reading my article on Austin Friars first. In that blog, I describe this remarkable property, its development in Cromwell’s hands, and the tale of Thomas’ rise to prominence.

Of course, as Cromwell’s career at court took off, so did his wealth. Like any ambitious courtier of the age, he was keen to acquire and develop property to reflect his position in society. Thus, we are left with a handful of glorious buildings (sadly now largely lost) attributed to Thomas’ home life. However, in this blog, I will turn my attention to a place that was effectively Cromwell’s London Office on Chancery Lane, known as ‘Rolls House’ or simply, ‘The Rolls’.

The Rise of The Rolls!

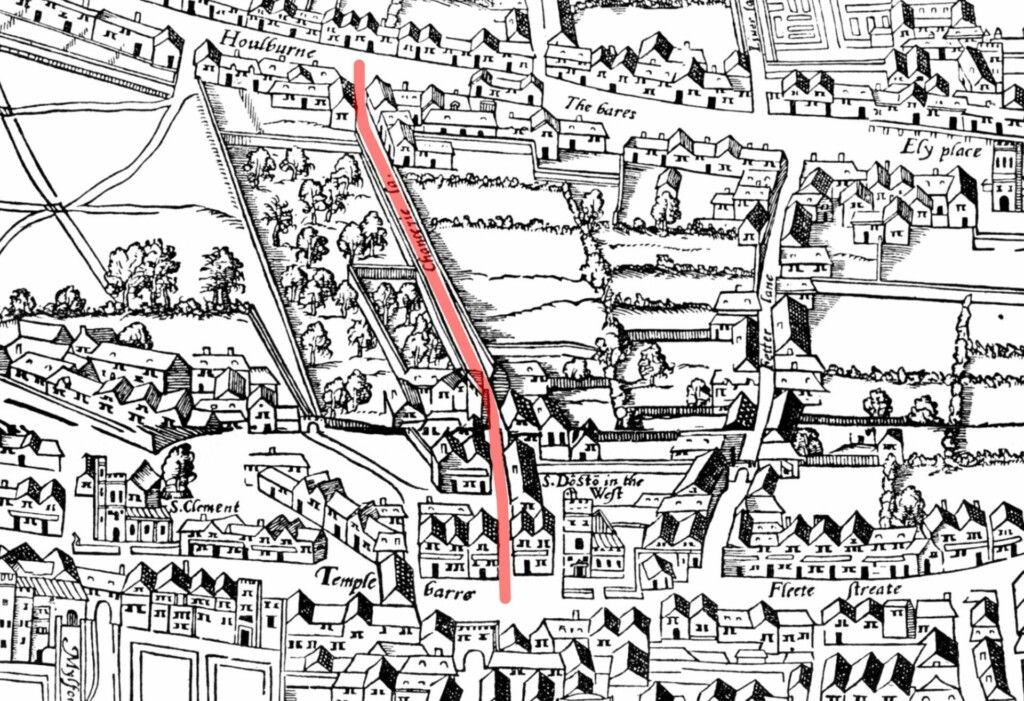

Sited just off Fleet Street (the main thoroughfare connecting The City of London with the royal enclave of Westminster), Chancellor’s Lane (now Chancery Lane) ran in a north-south direction. To the north was Holborn and beyond that, open countryside. To the south was Fleet Street, where the great houses of the clergy and nobility fronted onto the River Thames. The AGAS map of Early Modern London (see image below) shows the entrance to Chancery Lane. Straddling Fleet Street directly to the east of this southern entrance was Temple Bar, and directly west was the parish church of St Dunstan-in-the-West.

As Thomas Cromwell rode along Chancery Lane, he travelled along a street whose history stretched back to 1161. That year, the Knights Templar (a quasi-military monastic order) created a track connecting their original temple on Holborn with their newly acquired property south of Fleet Street. Around 70 years later, in 1232, this ‘New Lane’, as it was initially known, became the site of a Carthusian ‘house of maintenance’, the Domus Conversorum. The domus contained lodgings and a chapel for housing Jews who had converted to Christianity. From 1290, the man responsible for overseeing the work of the Domus was the Master of the Rolls, and the chapel became known as the Chapel of the Master of the Rolls, or Rolls Chapel.

After the dissolution of the Domus Conversorum in the fourteenth century, the Crown annexed the buildings, making the house and chapel the headquarters for the Master of the Rolls. The newly instituted office of Custos Rotulorum, or Keeper of the Rolls, was founded, and the now-disused spaces were repurposed to store the rolls and records of the Court of Chancery. These buildings became known as ‘Rolls House’ and ‘Rolls Chapel’. The role of The Master, or Keeper of the Rolls, has endured to this day. However, perhaps the most famous person to ever hold the title was our own Thomas Cromwell.

Taken from The AGAS map of Early Modern London.

Thomas Cromwell is Appointed Master of the Rolls

The primary responsibility of the Master of the Rolls was to keep the ‘Rolls’ or records of the Court of Chancery. This appointment was significant, second only in the legal hierarchy to the Lord Chief Justice of England. Before Cromwell, the men appointed were generally priests and often were the King’s chaplains. Several well-known names linked to Tudor history had previously held the post, including John Morton, Henry VII’s Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury; William Wareham, Archbishop of Canterbury to both Henry VII and Henry VIII; and Cuthbert Tunstall, later mentor to Katherine Parr. So, Cromwell was the first non-clerical appointment; it was conferred upon him on 8 October 1534.

According to Walter Thornbury’s account of Chancery Lane printed in Old and New London, ‘Half-way up on the east side of Chancery Lane a dull archway, through which can be caught glimpses of the door of an old chapel, leads to the Rolls Court.’ A view of these buildings was captured in one of the earliest maps of London, which was drawn by Braun and Hogenberg in 1572 (see image below). The close-up of Chancery Lane shows the buildings sited just off the street to the east; they sit at right angles to one another. On close inspection, you can see that one of these buildings has a central tower. I am guessing that this is ‘Rolls Chapel’.If I am correct, then, by deduction, the other (whose gable end faces towards us) must be ‘Rolls House’.

The two buildings in the centre of the image, standing at right angles to one another, (I believe) represent ‘Rolls House’ and ‘Chapel’. One has a central tower, which I suspect may have been ‘Rolls Chapel’, and the other is ‘Rolls House’.

This view would no doubt have been familiar to Cromwell as the map preceded the site’s redevelopment in 1617 when the medieval / Tudor buildings were significantly altered. Helpfully, to assist in reimagining Chancery Lane in the sixteenth century, Old and New London carries a fanciful, if not rather lovely, illustration of Thomas Wolsey in procession as he makes his way down the street at the height of his power (see image below). The fact that Wolsey once had an abode on Chancery Lane is undisputed. However, he was never Master of the Rolls, and according to Old and New London, his position at court at the time is unclear.

A second illustration from the same book is also shown here (see below). This was the house of Izaac Walton, author of the famous treatise on fishing, The Complete Angler. While his story is not of interest to us, the house is clearly Tudor and, once again, helps us pull back the veil of time and enter Cromwell’s world.

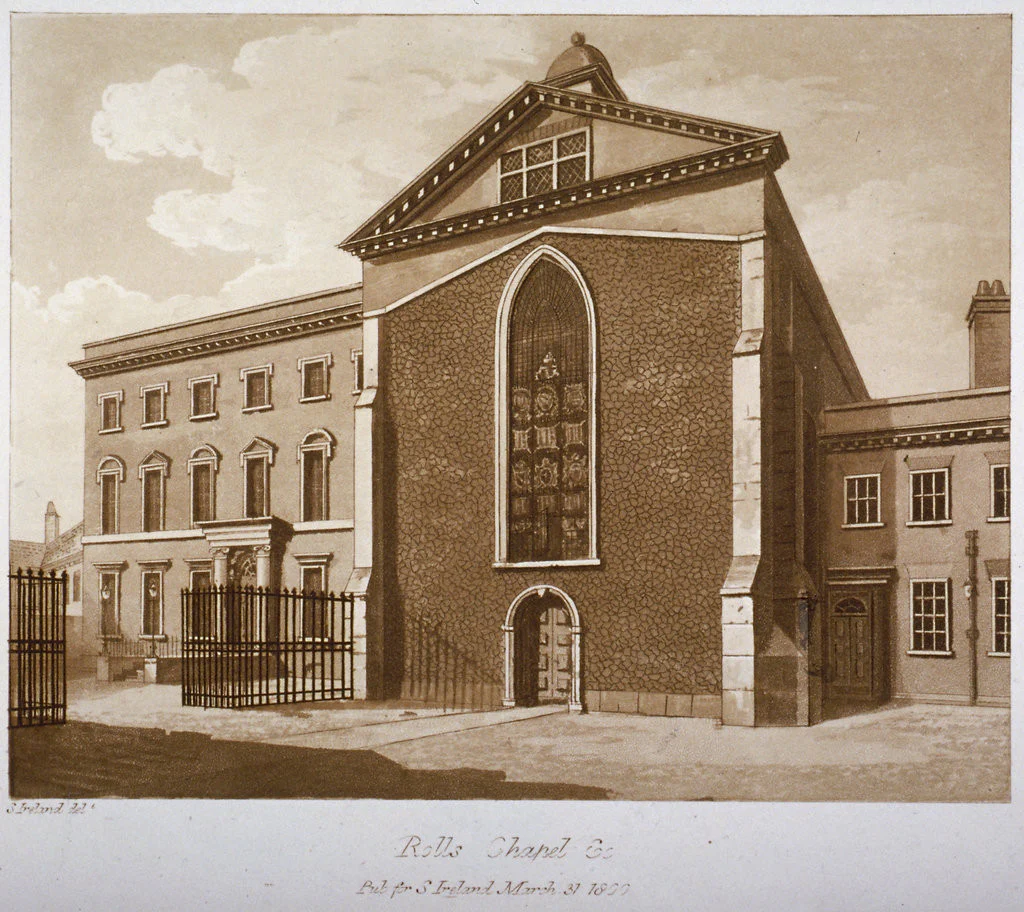

A mid-eighteenth-century account of the Rolls Chapel describes its appearance and how the space was used to store records. We should remember that by this time, the external appearance would have changed since Cromwell’s day following the redesign of the chapel in 1617. Nevertheless, it gives us an idea of its scale and that some features, such as its gothic windows, were retained.

‘The chapel, which is of brick, pebbles and some free stone, is 60 feet long, and 34 in breadth; the doors and windows are Gothic, and the roof covered with slate. In this chapel the Rolls are kept in presses fixed to the sides, and ornamented with columns and pilasters of the Ionic and Composite orders. These Rolls contain all the records, as charters, patents, &c. since the beginning of the reign of Richard III. those before that time being deposited in the Record office in the Tower: and these being made up in rolls of parchment gave occasion to the name. At the north west angle of this chapel is a bench, where the master of the Rolls hears causes in chancery: and attendance is daily given in this chapel for taking in and paying out money, according to order of court, and for giving an opportunity to those who come for that purpose, to search the Rolls. The minister of the chapel is appointed by the master of the Rolls, and divine service is performed there on Sundays and holidays.’

Thomas Cromwell’s City Office

As mentioned at the top of this article, like any Tudor courtier on the rise, Cromwell sought to expand his property portfolio to serve his personal and official needs. He acquired residences that were both convenient for transacting business and being close to the court, like Austin Friars and Mortlake, as well as others distant from the city that provided the Lord Privy Seal with comfortable country retreats, like Lord’s Place in Sussex and Launde Abbey in Leicestershire.

However, it is clear that acquiring these properties was not sufficient; Cromwell had a keen eye for developing each of his new residences. We can learn something of Cromwell’s assiduous application to the task of aggrandizing his principal houses from a flurry of letters exchanged between Master Secretary Cromwell and his Comptroller of the Household, Thomas Thacker, in the summer of 1535. This was the summer of the historic 1535 progress when Anne Boleyn spent her last summer on earth at her husband’s side, and Cromwell accompanied the royal couple for part of the geists.

This was when Cromwell was reaching the climax of his power, influence, and wealth. His courtly ambitions were matched only by the scale of the home improvement projects, which simultaneously gathered pace across the Cromwell property portfolio. It is probably not an over-exaggeration to say that no matter which residence Cromwell visited, he must have been greeted by the sounds of hammering and sawing and the smell of fresh paint!

Letters from Thacker to his master continuously refer to the current state of the building works at each of his properties, including ‘The Rolls’. So, for example, in one letter, written from ‘The Rolls’ and dated 11 August 1535 (when Cromwell was over on the other side of England in residence at Berkeley Castle), Thacker writes: ‘Your households at the Rolls, Friars Austins, Hackney, and Stepneth [sic], are in good health.’

Then, nine days later, Thacker is writing again from the Rolls, this time in response to Cromwell’s request for new clothes. These are dispatched the following day, and the letter closes with reassurance that his master’s home improvement plans are progressing smoothly. ‘I received your letter of the 16th to my great comfort. According to your writing, Mr. Williamson and I send you, by Ric. Swift, a black damask gown, new made and lined. We sent your coats on the 17th by John Tyny, who was then leaving London. Your buildings go forward with all diligence. The Rolls, 20 Aug.’

Clearly, the Rolls was a hive of activity, even in Cromwell’s absence. However, there were more challenging – and deadly – times ahead…

A Close Shave…

For the next section, I am indebted to Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, who was interviewed for the popular history podcast Travels Through Time. In this podcast, guests are asked to describe three places in time to which they would choose to return. Of course, as the author of Cromwell’s celebrated biography, Thomas was the man of the moment. Diarmaid’s third scene takes us to The Rolls, three days short of Christmas, on 22 December 1536. I will summarise the scene as it unfolds in Crowmell’s office. However, should you wish to listen to or read the account in full, you can find a link to the podcast and show notes page in the ‘Resource’ section below.

Diarmaid begins his narrative: ‘We’ve arrived on 22nd of December 1536, and the scene now is definitely in a room in the Rolls, just off Chancery Lane, and that’s within earshot of Fleet Street…’

1536 has been a difficult year for Cromwell. It opened with a titanic struggle between the King’s first minister and the Queen, Anne Boleyn. Cromwell emerged victorious, stepping over a series of bloodied, headless corpses to ingratiate himself further with his master, King Henry VIII. However, religious disquiet was brewing in northern England. This would soon erupt into an outright rebellion, known as The Pilgrimage of Grace. The rebels’ ire was directed towards the King’s advisors, namely Cromwell. At the mercy of the King’s whim, Cromwell endured the most dangerous few months of his life…

For a moment, it seemed as though Henry might sacrifice his First Minister to quell the rebellion, but ultimately, the King had stood by his man. By December, the danger had passed, and on the 22nd of December, as Christmas drew near, we find Cromwell in his office at Rolls House. Professor MacCulloch describes how, just yards away on Fleet Street, the King is processing amidst great pomp and celebration from his Palace of Whitehall to Greenwich, where he will spend Christmas.

‘He’s sitting in his study, his parlour, in the Rolls, thinking and probably smiling: ‘I’ve made it, I’ve made it through! And the King’s made it through, of course, his Grace has made it through and the pilgrims are happy because they’ve all gone home and they’ve been promised the earth and the one thing they haven’t been promised is me! They are not going to get me.’ And that had been their aim, right from the start, ‘we must destroy Thomas Cromwell! We must crumb and crumb him until he was never so crumbed’ and he is not being crumbed at all.’

Cromwell, that wily old fox, lived to fight another day. He had four years left to live.

The Demise of Rolls House

Sadly, nothing of Rolls House and very little of its adjacent chapel survive. At the beginning of the seventeenth century (1617), ‘The Rolls’ was redeveloped. Inigo Jones was the first to redesign the chapel. The building then underwent further alterations in 1734 and again in 1784. The records held there were finally moved in 1856, and the chapel was demolished in 1895.

The Weston Room of the rather fabulous Maughan Library, part of King’s College, now occupies the site of the original chapel. This was designed by Sir James Pennethorne and was rebuilt from 1851 to 1890. Only a tiny fragment of the medieval church remains. These include an arch mounted on the garden elevation of the Chancery Lane wing, three funerary monuments, stained glass panels and a mosaic floor.

One of the funerary monuments is of particular note: the monument is in remembrance of Dr John Yonge (died 1516). He was Master of the Rolls during the reign of Henry VIII. His tomb was sculpted by Pietro Torrigiano, who is famous for carving the tombs of Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort in Westminster Abbey.

Unfortunately, I have found very little information on the fate of the Medieval/Tudor ‘Rolls House’. The image above (dated 1800) may or may not give us an idea of its Tudor appearance. Thinking about the Braun and Hogenberg plan of Chancery Lane shown at the top of this article, I wonder whether the remains of the original (Tudor) house lie to the right of the chapel and whether the building on the left is a later addition. The former certainly has an earlier architectural design that hints towards some Tudor features. If anyone knows more or has an expert opinion on this, I’d love to hear it!

Either way, nothing now remains above ground of Cromwell’s city office. What was once a hive of activity and intrigue has fallen eternally silent, all vestiges buried beneath the heart of London’s legal centre, taking its secrets to the grave.

Sources

Sources that I have found most helpful in writing this article:

John Stow, ‘The warde of Faringdon extra, or without‘, in A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603, ed. C L Kingsford (Oxford, 1908).

Walter Thornbury, ‘Fleet Street: Northern tributaries – Chancery Lane‘, in Old and New London: Volume 1 (London, 1878).

Travels Through Time with Diarmaid MacCullouch.