Plague, Power, and the Cromwells: The Story of Swanborough Manor

One of the delightful things about researching this series is how uncovering the history of one location has unearthed yet more historic properties that were once part of the Cromwell property portfolio. This is certainly the case for Swanborough Manor, whose name first came to my attention in a letter written from Lewes about the worrying plight of Gregory Cromwell and his wife, Elisabeth.

Plague was rife in the town at the time, and clearly, Thomas Cromwell was concerned for the safety of his only remaining child, Gregory. His ‘paranoia’ is understandable, given that he had already lost his wife and two daughters, Anne and Grace, to the Sweating Sickness in 1529.

The letter reads:

‘…The other house, called Swanborough, is a mile from Lewes but is thought too little for Mr. Gregory’s company. None have died for eight days, and none are sick of the plague now within the town. I send you a bill of the number of persons to attend on Mr. Gregory on his removal, and of those appointed to be on board wages. Lewes, 24 May.

The manor referred to in the above letter survives as a private residence. However, unsurprisingly, the interiors have been significantly altered over the intervening centuries, and one external facade has been given a Georgian makeover. Nevertheless, many original medieval and Tudor features survive.

As far as I know, Thomas Cromwell never visited Swanborough, although, as mentioned above, Gregory, his son, considered it as a refuge from the plague. Regardless, I have decided to include this manor in my series on The World of Thomas Cromwell as a fine and surviving example of a satellite property connected to a primary residence (in this instance, Lord’s Place), which was given to Cromwell as a result of the Dissolution of the Monasteries and subsequently utilised as a source of income. I have little doubt that Cromwell owned a healthy portfolio of such manors, which he never visited; however, they allowed him to accumulate wealth and status as a local landowner.

In this section, I will describe how the manor came into Cromwell’s ownership, what was known of its appearance when Gregory Cromwell, or the gentlemen of his household, inspected it as a potential escape from the pestilence, and what remains to be seen today.

A Brief History of Swanborough Manor

Swanborough Manor was once part of an ancient Anglo-Saxon territory known as the ‘Hundred of Swanborough’. A ‘hundred’ was an old administrative division used in England during that period. It described a geographic area typically supported by about a hundred households, hence the name. ‘Hundreds’ were used for administrative, judicial, and military purposes and were part of the larger shire or county system.

One of the earliest land ownership records in the Swanborough Hundred shows its connections to Anglo-Saxon royalty. In 1045, it formed part of the dowry of Edith of Wessex, the daughter of Earl Godwin, who married King Edward the Confessor. Edith was the last Anglo-Saxon Queen of England and the wealthiest person in the realm when Edward died in 1066.

Of course, the resulting struggle for the English throne brought William the Conqueror to power. The new dominant overlords redistributed territory and wealth among the invaders, giving land in and around Lewes, including the Hundred of Swanborough, to William de Warenne, the new King’s son-in-law. As seen in the entry for Lord’s Place, in 1078, William de Warenne and his wife Gundrada established the first Cluniac Priory in England in Lewes. Thus, we enter the town’s golden age, with its flourishing monastic community, which was foremost amongst the Cluniac order in England.

From 1080 onwards, when William de Warenne ‘gave to God and the Abbot of Oluni five hides and a half of land in Swambergh’, we see the priory begin the process of accumulating land and property in the area surrounding the town.

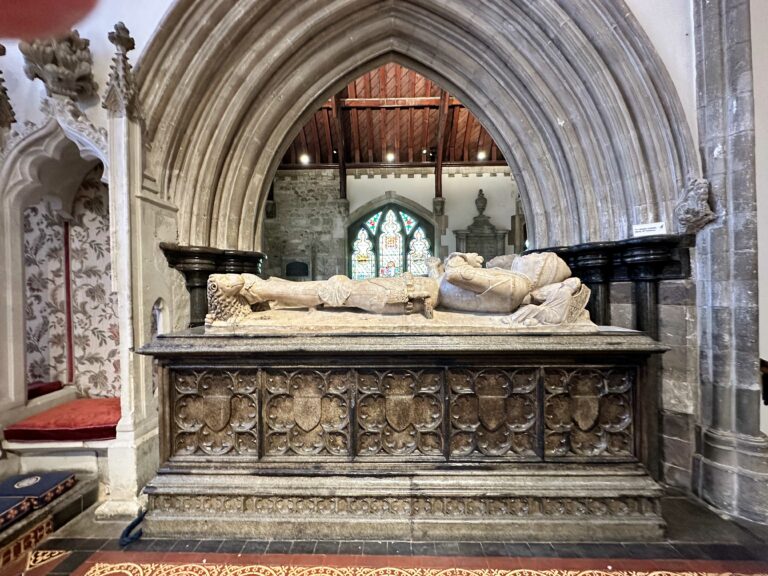

Image from Country Life magazine – November 1934.

A summary of the principal ownerships and grants of land in the Hundred of Swanborough is given in The Hundred of Swanborough by J. Cooper. In it, we see that from the eleventh to the late fourteenth centuries, wealthy landowners bequeathed gifts to the priory, often in exchange for salvation for their soul at death or that of a deceased relative. In this way, at some point, the manor of Swanborough came into the ownership of the Priory at Lewes.

Swanborough: A Monastic Grange

The images reproduced in this blog are taken from a 1934 copy of Country Life, which featured Swanborough Manor in its November edition. They neatly summarise the manor’s purpose: ‘It was part of the domestic economy of the monasteries to run their estates and gather their harvest from granges which were often identical with manor houses.’ This was the function of Swanborough Manor through the medieval period before the Dissolution of the Priory at Lewes in 1538.

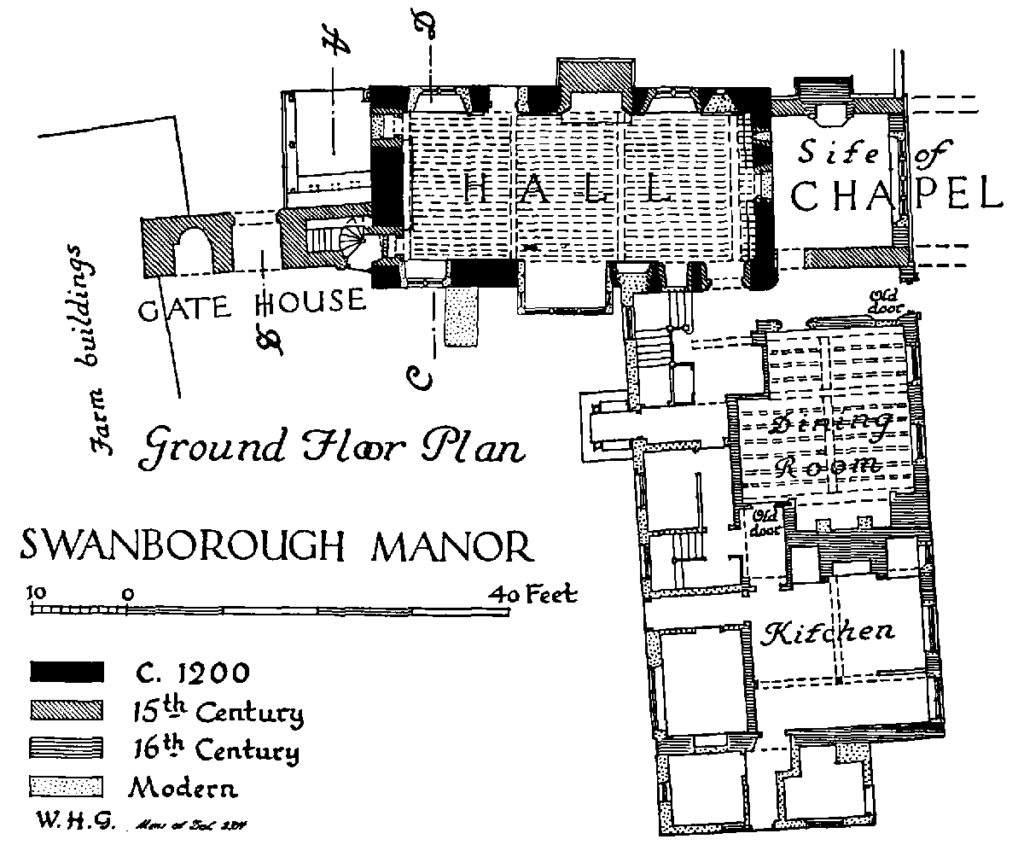

The earliest part of the surviving house reflects these medieval origins. The manor has two surviving ranges – the northern (medieval) and eastern (post-Reformation/Tudor) ranges. The article in Country Life states that there was also ‘…a former wing, now vanished…on the west, the court being probably enclosed by a southern range with the principal gatehouse of which no trace now exists.’ In other words, this seems to have been a single courtyard manor house of modest proportions, confirmed by Cromwell’s household, who thought it too small to accommodate ‘Mr Gregory’.

As this was originally a monastic property, the heart of the manor consisted of a Great Hall, Chapel, dormitory, kitchen, and other service offices. Some of the additional living spaces seen in the country houses of the lay folk were unnecessary. I suspect the accommodation areas were expanded and developed over time, particularly in the post-dissolution period.

The northern range contained ‘the original hall, lying east and west and measuring internally 37 ft. by 15½ ft., [it] was built about 1200.’ At the end of the fourteen or the beginning of the fifteenth century, a floor was inserted, creating two storeys from the original single lofty space. These became known as the upper and lower halls. According to British History Online, the latter may have served as either a hall or a dormitory.

The ‘superb’ curved oak roof of the upper hall survives, while both halls have fireplaces of sixteenth-century design. Quatrefoils and other carved stones have been built into the large chimney stack, suggesting they may have come from the demolition of Lewes Priory. Therefore, these sixteenth-century additions may well have been the work of the Cromwells.

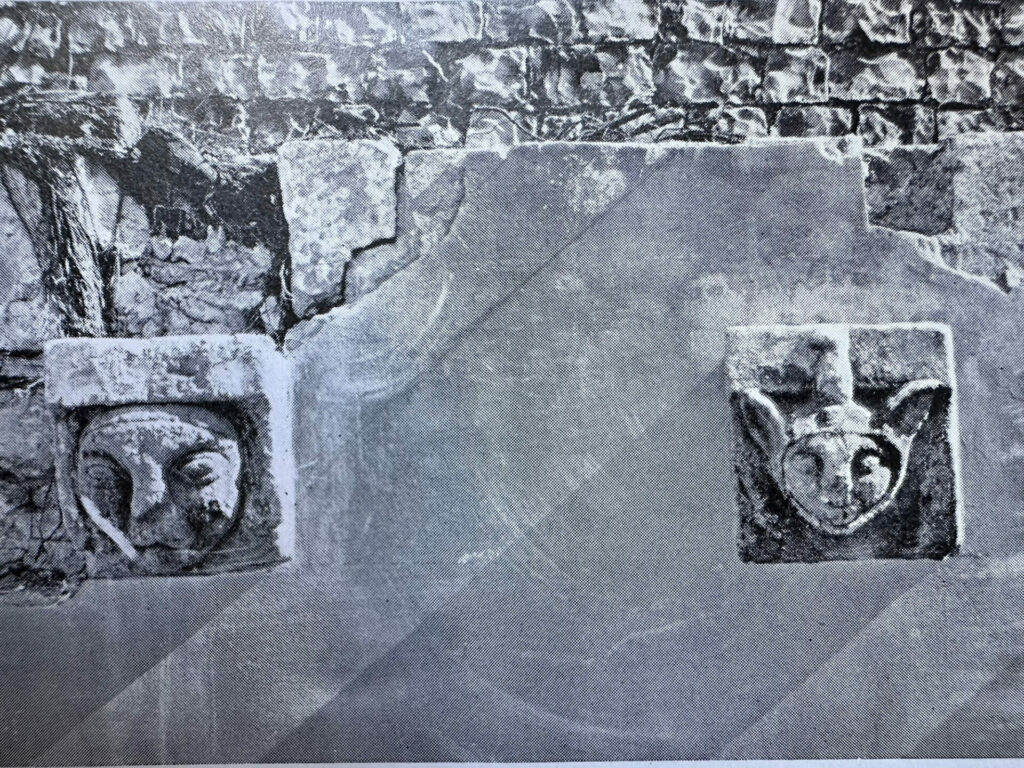

Still in this northern range, a door in the lower end of the upper hall once connected the range to the western block via a passageway which ran above a small, fifteenth-century ‘inner’ gatehouse. While this gatehouse survives, the passageway was later converted to a dovecote, and the western range was lost. On the ground floor, there are two blocked-up doorways (see image above). The southern doorway led to a newel staircase leading up to the aforementioned passageway, while the northern one opened into ‘a single-story room, presumably the buttery pantry.’

At the high end of the hall, adjoining it to the east, was a chapel. An arched doorway in the centre of the eastern wall of the lower hall led directly through into this space. Today, the chapel has been truncated and turned into a living space.

Another door on the southern side of the hall’s high end leads to the surviving east range, which, according to the usual layout of a manor house of the period, would have included additional living quarters and any higher-status rooms.

From the architecture of this eastern range, it is thought to have been ‘probably built immediately after the Dissolution in the reign of Henry VIII’. The article in Country Life describes this wing as having ‘fine oak-beamed floors, and roofs and some good moulded doorways cut out of solid oak.’ If the date attributed to this range is accurate, then much of what we see today could also be the work of Thomas Cromwell. Although he only owned the property for two years after it had been granted to him in 1538, as we have seen at other properties, the Lord Privy Seal was always quick to apply his wealth to improve his properties.

Like many fragments of England’s past, Swanborough Manor remains a silent witness to centuries of evolving English history. From its Anglo-Saxon roots to its life as a monastic grange and its fleeting place in the Cromwell portfolio, its walls have seen ambition, faith, and survival play out across the centuries.

Though its medieval heart still beats beneath later alterations, Swanborough remains a tangible link to the world Thomas Cromwell once shaped—a world where power was measured in land, legacy, and the ever-present spectre of fortune’s rise and fall. One can almost imagine Gregory Cromwell or members of his household standing in its halls, weighing its worth as a refuge from the plague, blissfully unaware that their master’s fate would soon hang in the balance.

Visitor Information

Swanborough Manor is in private ownership and cannot be visited.

Glossary:

Quatrefoil: A quatrefoil is a decorative design element that consists of four overlapping or adjacent circles, creating a shape that resembles a four-leaf clover. The term comes from the Latin quattuor (meaning “four”) and folium (meaning “leaf”).

In architecture, quatrefoils are commonly found in Gothic and medieval designs, often carved into stone tracery, windows, and reliefs. They symbolize harmony, symmetry, and sometimes religious themes. You’ll frequently see them in church windows, heraldry, and decorative elements of Tudor and medieval buildings—like those in Swanborough Manor!

Buttery: A buttery in a medieval or Tudor household was a storage and service room used primarily for keeping and dispensing beverages, particularly ale and wine. It was typically located near the great hall and was managed by the butler, whose job was to oversee the household’s drink supply.

The buttery often had barrels, casks, and shelves for storing liquids and could also serve as a place to prepare drinks before serving them in the hall. It was distinct from the pantry, which stored dry goods and bread, and the kitchen, where food was prepared.

In larger manor houses and castles, the buttery was part of a suite of service rooms, including the pantry and larder, which together ensured the smooth running of the household’s food and drink provisions.

Sources:

Swanborough Manor, Lewes, Sussex. The Residence of Mr. Cecil Harrison. Country Life, Vol LXXIV – No 1972. November 1934 p.472-477.

Cooper, J. (1879). The Hundred of Swanborough. Sussex Archaeological Collections 29. Vol 29, pp. 114-166

Parishes: Iford’, in A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 7, the Rape of Lewes, ed. L F Salzman (London, 1940), British History Online.